2.1: The Campanile, Cathedral (Duomo), and Baptistery

We are now at the ritual centre of Florentine interest, the Piazza San Giovanni, the Square of the Cathedral (1296).

Reparata was for six hundred years (from 680 to 1296) the chief patroness of Florence. According to the old Florentine legend, she was a virgin of Cesarea, in the province of Cappadocia, and bravely suffered a cruel martyrdom in the persecution under Decius, when only twelve years old. She was, after many tortures, beheaded by the sword; and as she fell dead, her pure spirit was seen to issue from her mouth in form of a dove, which winged its way to heaven.

The Duomo at Florence was formerly dedicated to S. Reparata; but about 1298 she appears to have been deposed from her dignity as sole patroness; the city was placed under the immediate tutelage of the Virgin and S. John the Baptist, and the Church of S. Reparata was dedicated anew under the title of Santa Maria del Fiore.

Anna Jameson, Sacred Art, vol. 2, p. 648.

The Duomo was called S. Maria del Fiore, in allusion to the lily in the city arms, which marks the tradition that Florence was founded in a field of flowers. The noble document by which the building of this cathedral was decreed shows that the city was then governed by a body of men representing all the force and intelligence of the State. “Since,” it says, “the highest mark of prudence in a people of noble origin is to proceed in the management of their affairs so that their magnanimity and wisdom may be evinced in their outward acts, we order Arnolfo, head-master of our commune, to make a design for the restoration of S, Reparata in a style of magnificence which neither the industry nor power of man can surpass, that it may harmonise with the opinion of many wise persons in this city and State, who think that this commune should not engage in any enterprise, unless its intention be to make the result correspond with that noblest sort of heart which is composed by the united will of many citizens.”

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors vol. 1, p. 54.

The effect of the admirable grouping of the buildings is possibly enhanced by the confined space in which they are situated.

Arial view of the Duomo, Baptistry, & Campanile (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

We must consider all the conditions under which the great works of the old architects were constructed, and that it is probable in many cases that the very confined space in which they were built was considered in their design, and by increasing the space around them we may seriously belittle them.

Signor del Moro, in charge of the architectural works at Florence.

Recent researches have demonstrated clearly that both the design and the execution of this wondrous monument, with which the Middle Ages were brought to a close and the Renaissance opened, was not the creative effort of one master-artist, but on the contrary was a collective precipitation, to which contributed, both the thought, labour, and criticism of artists, monks, and citizens. So that this astonishing entirety, which at first seems to us to have been the design of a single sovereign mind, is in reality the projection of Florentine civilisation, of fervid and brilliant Tuscan genius kindled and maintained by intense love of the fatherland. The story of it reveals to us how often an unfamed, even humble, artist was destined to win renown and advancement in the prolonged course of this truly mighty world of labour.1The translation given in the 9th edition varies somewhat from the text quoted in Cavallucci: I nuovi studi ci hanno pur dimostrato come il concetto e la esecuzione di quel monumento magno, con cui si chide il periodo medio evale dell’architettura e si apre quello del risorgimento, non si appartenga ad un solo artista, ma sia invece opera collettiva alla quale concorsero col consiglio e con l’opera, artisti, artieri, claustrali, e cittadini. Così quell’assieme maraviglioso, che a noi sembra essere uscito di getto dalla mente di un’ingegno sovrano, è il portato della civiltà dei fiorentini, l’ opera di menti fervide e pronte scaldate dal fuoco dell’amor di patria… e la storia ci mostra come degli umili artigiani, bene spesso, più di uno giungesse a conquistare la rinomanza e gli uffici dell’emulo in quella lotta diuturna di ingegno, di operosità, e di virtù cittadine.

J. C. Cavallucci, S. Maria del Fiore, pp. xi–xii.

Forty years ago, there was assuredly no spot of ground, out of Palestine, in all the round world, on which, if you knew, even but a little, the true course of that world’s history, you saw with so much joyful reverence the dawn of morning, as at the foot of the Tower of Giotto. For there the tradition of faith and hope, of both the Gentile and Jewish races, met for their beautiful labour; for the Baptistery of Florence is the last building raised on the earth by the descendants of the workmen taught by Daedalus; and the Tower of Giotto is the loveliest of those raised on earth under the inspiration of the men who lifted up the tabernacle in the wilderness. Of living Greek work there is none after the Florentine Baptistery; of living Christian work, none so perfect as the Tower of Giotto; and under the gleam and shadow of their marbles, the morning light was haunted by the ghosts of the Father of Natural Science, Galileo; of Sacred Art, Angelico; and the Master of Sacred Song.

John Ruskin, Mornings in Florence, pp. 157–58.

Immediately in line with the West front, to the right of the Cathedral, stands the beautiful Gothic Campanile of Giotto and Francesco Talenti, occupying the site of an oratory of S. Zanobio, “in which the Seven Servants of the Blessed Virgin were miraculously called to lead a life of contemplation.”

The characteristics of Power and Beauty occur more or less in different buildings, some in one and some in another. But all together, and all in their highest possible relative degrees, they exist, as far as I know, only in one building in the world, the Campanile of Giotto. . . . In its first appeal to the stranger’s eye there is something unpleasing; a mingling, as it seems to him, of over-severity with over-minuteness. But let him give it time, as he should to all other consummate art. I well remember how, when a boy, I used to despise that Campanile, and think it meanly smooth and finished. But I have since lived beside it many a day, and looked out upon it from my windows by sunlight and moonlight, and I shall not soon forget how profound and gloomy appeared to me the savageness of the Northern Gothic, when I afterwards stood, for the first time, beneath the front of Salisbury. The contrast is indeed strange, if it could be quickly felt, between the rising of those grey walls out of their quiet swarded space, like dark and barren rocks out of a green lake, with their rude, mouldering, rough-grained shafts and triple lights, without tracery or other ornament than the martins’ nests in the height of them, and that bright, smooth sunny surface of glowing jasper, those spiral shafts and fairy traceries, so white, so faint, so crystalline, that their slight shapes are hardly traced in darkness on the pallor of the Eastern sky, that serene height of mountain alabaster, coloured like a morning cloud and chased like a sea-shell. And if this be, as I believe it, the model and mirror of perfect architecture, is there not something to be learned by looking back to the early life of him who raised it? I said that the Power of human mind had its growth in the Wilderness; much more must the love and the conception of that Beauty, whose every line and hue we have seen to be, at the best, a faded image of God’s daily work, and an arrested ray of some star or creation, be given chiefly in the places which he has gladdened by planting there the fir-tree and the pine. Not within the walls of Florence, but among the far-away fields of her lilies, was the child trained who was to raise that head-stone of Beauty above her towers of watch and war. Remember all that he became; count the sacred thoughts with which he filled the heart of Italy; ask those who followed him what they learned at his feet; and when you have numbered his labours and received their testimony, if it seem to you that God had verily poured out upon this His servant no common nor restrained portion of His Spirit, and that he was indeed a king among the children of men, remember also that the legend upon his crown was that of David’s —“I took thee from the sheepcote, and from following the sheep.”

John Ruskin, Seven Lamps of Architecture, p. 135.

In the old Tuscan town stands Giotto’s tower,

The lily of Florence blossoming in stone,

A vision, a delight, and a desire,

The builder’s perfect and centennial flower,

That in the night of ages bloomed alone,

But wanting still the glory of the spire.

H.W. Longfellow, Flower-De-Luce: Giotto’s Tower.

The bas-reliefs round the basement storey of the tower were designed by Giotto and Andrea Pisano. The former is believed to have executed those of Sculpture and Architecture, the rest being carried out by Luca della Robbia in the 15th century. In the second or succeeding tier are sixteen statues, several of them by Donatello. [Copies have replaced the originals, which are now housed in the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo.]

The tower is ascended by 414 steps.

The bas-reliefs round the basement storey of the tower were designed by Giotto and Andrea Pisano. The former is believed to have executed those of Sculpture and Architecture, the rest being carried out by Luca della Robbia in the 15th century. In the second or succeeding tier are sixteen statues, several of them by Donatello. [Copies have replaced the originals, which are now housed in the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo.]

The tower is ascended by 414 steps.

Emilio de Fabris, Duomo West façade, 1887 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Gothic Cathedral—Santa Maria del Fiore—was begun (on the site of the Church of S. Reparata)2Hare claims that the prior church was dedicated to S. Salvatore. S. Reparata was martyred during the reign of Decius (249-251) in 1296 by Arnolfo di Cambio, who was desired to build “the loftiest, most sumptuous edifice that human invention could devise or human labour execute.” He, however, died in 1301, and it would seem that the work was suspended. The magnificent conception of Arnolfo “lavoro di poesia” [poetic work] was, however, dwarfed in execution. In 1334 the work begun by Arnolfo was entrusted to Giotto, who designed the tower and continued to work for three years, when he was succeeded by Andrea da Pontedera. About 1350 Francesco Talentibecame elected Master-Architect, and worked for years on both the church and Campanile; and it is to him we owe the most part, probably, of the remaining work. A beautiful façade, on which many of the best sculptors of the time were employed, was erected soon after the death of Giotto, but was destroyed in 1515–87.3Any one who wishes to know what the old façade was like should find, on the south side of the first cloister of S. Marco, the picture of Archbishop S. Antonino making his solemn entry to the Duomo in 1446. It is; probable, moreover, that whatever may have been the original design of Arnolfo di Cambio, it was greatly modified in the prolonged period of construction. The uninteresting modern façade, commemorating the short period during which Florence was the Italian capital, is from the designs of E. de Fabris, whose portrait bust by Vincenzo Consani is to be found within the Duomo. The passage of time has modified Hare’s critical evaluation.

Niccolò di Piero Lamberti, Porta dei Canonici, 1402 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Nanni di Banco, Assumption of the Virgin, 1414-21 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The exterior of the cathedral is encrusted with precious marbles and polychromatically enriched with sculpture in peculiar contrast to the dim and naked interior. The northern porch is especially rich; also the southern side-door nearest the apse—Porta dei Canonici—with a Madonna and child by Lorenzo di Giovanni D’Ambrogio (1402). A garland of fig-leaves by Pietro di Giovanni (1395). The beautiful Porta di Mandorla(N.) is by Niccolò Aretino, and has a mosaic of the Annunciation by Dom. Ghirlandajo. The famous Madonna above it is the work of Nanni di Banco (1418).

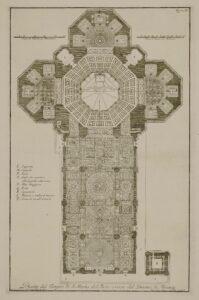

Until the fifteenth century, the cathedral had only a wooden cupola. Brunelleschi in 1417 first suggested an octagonal cupola to rest upon a drum raised above the roof, and in 1420 he was accepted as architect. Then, as [Jules] Michelet says, “the colossal church stood up simply, naturally, as a strong man in the morning rises from his bed without the need of staff or crutch.” It has the earliest double cupola, and probably the widest, in Europe. Its scientific beauty is great, but it is too large for perfect aesthetic effect.

Domes had been constructed not so long before at Pisa, Siena, and at S. Marco in Venice, but none of them on such a grand scale, the diameter being one hundred and thirty-eight and a half feet, and the altitude of the dome itself one hundred and thirty-three feet, measured from the cornice to the eye of the dome. The difficulties of so large a construction were much increased by the adoption of the drum on which the dome is raised, and through which it is lighted. There is a separation between the inner and outer shell of the dome, but they are concentric, or nearly so. As the altitude of the dome is in itself too great for good proportion internally or for decorative effects, the result might have been finer had the inner dome parted company from the outer with a lower centre; but that would have increased the thrust at the top of the drum, which it was Brunelleschi’s aim to reduce to a minimum; hence the acutely-pointed form of both domes.

William Anderson, R.I.B.A., The Architecture of the Renaissance in Italy, p. 15, 1901.

When, a century afterwards, Michelangelo was desired to surpass, in S. Peter’s at Rome, the work of Brunelleschi, he replied—

Io farò la sorella

Più grande già, ma non più bella.

I will be the sister

Bigger yes, but not more beautiful.

Filippo Brunelleschi, Lantern on the Duomo

1436-70 (photo Britannica)

Plan S. Maria del Fiore (Duomo), 1733-55 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

It was completed in 1461 after Brunelleschi’s decease. The ball and cross were added by Andrea Verocchio in 1469.

Designed on a Latin-cross plan, the general effect of the Interior is bare, like a riding school, and chilling. It is built of Pietra Serena—a sandstone quarried N. of the city in a tertiary formation, the poetic quality of which does not appear, though its constructional virtue is undeniable.

Duomo Nave looking East (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

To tell the truth, the Duomo at Florence is a temple to damp the spirit, dead or alive, by the immense impression of stony bareness, of drab vacuity, which one receives from its interior, unless it is filled with people.

W. D. Howells, Tuscan Cities, p. 55.

The chief colour comes from the rich but very dirty stained glass of the narrow windows. The arches are of such great span that there are only four bays forming the aisles on either side of the nave.

Like all inexperienced architects, Arnolfo seems to have thought that greatness of parts would add to the greatness of the whole, and in consequence used only four great arches in the whole length of his nave, giving the central aisle a width of fifty-five feet clear. The whole width is within ten feet of that of Cologne, and the height about the same, and yet, in appearance, the height is about half, and the breadth less than half, owing to the better proportion of the parts and to the superior appropriateness in the details on the part of the gothic cathedral.

James Fergusson, Illustrated Handbook of Architecture, vol. 2, p. 774.

Proceeding round the church from the west door, we find the interesting frescoed memorial by Paolo Uccello in terra verde to Giovanni Aguto, or Sir John Hawkwood,4Arms of Hawkwood: Argent, on a chevron sable, 3 scallops. The monument was transferred to canvas in 1845. a captain of a Free Company, who, from 1364, for thirty years, “led a soldier’s life in Italy, fighting first for one town and then another—here for bishops, there for barons, but mainly for those merchants of Florence from whom our Lombard Street is named.”5See Ruskin, “Fors Clavigera.” He did not scruple to transfer his services from one Lordship to another for higher payment, and Forsyth not inaptly describes his portrait as “prancing over the military praise which he obtained by traitorously selling to Florence the Pisans who paid him to defend them.” The funeral obsequies of Sir John in 1394 were most sumptuously carried out, the Signoria providing the black dresses even for his widow, son, and daughters, and their households; while the bier, draped in crimson and gold, was brought into the great Piazza with 100 torches, the banners of all the Guilds, accompanied by fourteen caparisoned charges led by some of Hawkwood’s lancers, together with his sword, shield, helmet, and pennon bearing a harpy. All the shops were closed, and the community was dressed in black, the bells all over the city pealing solemnly. The body was then borne, first to the Baptistery, and there exposed with the sword laid upon the breast and the baton clenched in the right hand, surrounded by torches and weeping women. Thence, it was carried across to the Duomo, where a funeral oration was pronounced and the great captain was temporarily laid to rest in the choir. Later his remains were transferred by request of Richard II. to England, and passed on to Sable Hedingham in Essex, where Hawkwood’s lands lay, and where a chantry chapel became endowed for the maintenance of a priest to pray for his soul. The magistrates of Florence wrote:

Although we should consider it glorious for us and our people to possess the dust and ashes of the late valiant knight, nay, most renowned captain, Sir John Hawkwood, who fought most gloriously for us as the commander of our armies, and whom at the public expense we caused to be interred in the Cathedral Church of our city; yet, notwithstanding, according to the form of the demand, that his remains may be taken back to his own country, we freely concede the permission, lest it be said that your sublimity asked anything in vain, or fruitlessly, of our reverential humility.

They seem quite to have forgotten the monies due to their bankers since 1343.

Hawkwood appears to me the first real general of modern times; the earliest master, however imperfect, in the science of Turenne and Wellington. Every contemporary Italian historian speaks with admiration of his skilful tactics in battle, his stratagems, his well-conducted retreats. Praise of this kind is hardly bestowed, certainly not so continually, on any former captain.

Henry Hallam, Europe during the Middle Ages, vol. 1, p. 474.

Also by Paolo Uccello are four heads of prophets, at the angles of the clock. Over the S. door is a portrait of the Condottiere Niccolò Marucci da Tolentino, 1434, by Andrea del Castagno. Above is a round window.

Buggiano, Bust of Filippo Brunelleschi, 1447-48 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

In the S. aisle are the monuments of Brunelleschi, with a bust by his pupil, “Il Buggiano” and an epitaph by Carlo Marsuppini; and of Giotto, placed here in 1490 by Lorenzo de’ Medici, with a bust and ornamental frame by Benedetto da Majano, and an epitaph by Politian. On the opposite column is a portrait of S. Antonino, the beatified Dominican bishop and chronicler, by Francesco Morandi.

Over the first door is the monument of Pier Farnese, another captain of Free Companies, who died of the plague in 1363. It was formerly surmounted by an equestrian statue. Beyond the next column is a statue of Hezekiah by Nanni di Banco. Then comes the monument of Marsilio Ficino, an illustrious humanist, born 1433, who was first President of the Platonic Academy. His bust is by Andrea Ferrucci da Fiesole (1521).

Over the second door—Porta del Capitolo—is the monument by Tino di Camaino of the Bishop Antonio d’ Orso, who, in 1312, led his canons out in armour against Henry VII., Dante’s ideal emperor, when he was beleaguering Florence. When his tomb was removed hither in 1843, his body was found in perfect preservation. The family of Orsi still exists in Florence.

The stained windows of the S. transept are good works of Domenico Livi da Gambassi, c. 1434.

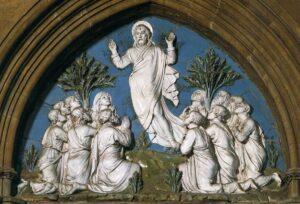

Luca della Robbia, Ascension of Christ, 1446 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The lunettes over the doors of the two Sacristies—simple white on a blue ground—are among the earliest works of Luca della Robbia,6Luca di Simone della Robbia was born in 1388 in his family house near S. Barnaba in the Via dell’ Acqua. and represent the Ascension and the Resurrection. It was to the Sagrestia Vecchia that Lorenzo de’ Medici escaped, after seeing his brother Giuliano killed before the altar, in the conspiracy of the Pazzi, Sunday, April 26, 1478. Politian, who was with him, secured the door against the enemy, while Antonio Ridolfi sucked his wound, lest it should have been poisoned.

The moment when the priest at the high altar finished the mass, was fixed for the assassination. Everything was ready. The conspirators, by Judas kisses and embracements, had discovered that the young men wore no protective armour under their silken doublets. Pacing the aisle behind the choir, they feared no treason. And now the lives of both might easily have been secured, if at the last moment the courage of the hired assassins had not failed them. Murder, they said, was well enough, but they could not bring themselves to stab men before the consecrated body of Christ. In this extremity a priest was found, who, “being accustomed to churches,” had no scruples. He and another reprobate were told off to Lorenzo. Francesco de’ Pazzi himself undertook Giuliano. The moment for attack arrived. Francesco plunged his dagger into the heart of Giuliano. Then, not satisfied with this death-blow, he struck again, and in the heat of passion wounded his own thigh. Lorenzo escaped with a flesh-wound from the poniard of the priest, and rushed into the sacristy.

J. A. Symonds, Sketches and Studies in Italy, pp. 148–49.

Behind the high altar was a Pietà, [now in the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo] an unfinished and, the inscription says, last work of Michelangelo, executed in 1555, when he was in his eighty-first year. The wooden crucifix over the altar is by Benedetto da Majano. Beneath the central altar of the apse is the famous Shrine of San Zenobio (“Arca di S. Zenobio”) by Ghiberti, 1446.

Beautiful, indeed, is the relief upon its front, which represents the miraculous restoration of a dead child to life by the Saint, in the presence of his widowed mother. In the centre lies the body, over which the spirit hovers in the likeness of a little child, between the praying Saint and the kneeling mother, around whom cluster a crowd of spectators. The story is exquisitely told, the kneeling figures are full of feeling, the bystanders of sympathy, and the vanishing lines of the perspective are managed with wonderful skill, so as to lead the eye from the principal group, through the nearer and more distant spectators, to the gates of the far-off city. Two other miracles of the Saint are represented on the ends of the “Cassa,” and at the back are six angels in relief, sustaining a garland, within which is an inscription commemorative of this holy and learned man, who abjured Paganism in his early youth, bestowed his private fortune upon the poor, and was made one of the seven Deacons of the Church by Pope Damasus; he was subsequently Legate at Constantinople, and at the time of his death held the office of Bishop of Florence.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, pp. 133–34.

We can say that the memory of a saint had never been consecrated by such a monument. From the point of view of art proper, all imaginable perfections are affected.

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, vol. 1 (1861), p. 305.

Formerly in the chapels of the apse were four Evangelists, now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo.

Nanni di Banco. S. Luke, 1408–15

Donatello. S. John the Evangelist, 1410–11

Donatello. S. Matthew,

Niccolò Aretino. S. Mark, 1410–15

Luca della Robbia, New Sacristy doors, 1446-75 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The Sagrestia Nuova (della Messa) has pannelled bronze doors by Luca della Robbia and Maso di Bartolommeo, and contains inlaid wardrobes by G. di Maiano.

In the N. transept is a gnomon invented in 1468 by the Florentine Paolo Toscanelli. Here are fresco portraits, of Pietro Corsini, Bishop of Florence, 1405, by Santi di Tito, and of Luigi Marsili learned theologian, 1394, by Bicci di Lorenzo. In a niche of one of the dome pillars is a S. Jacopo, by Sansovino, 1517.

Over the first door, on entering the north aisle from the east, is the tomb of Aldobrandino Ottobuoni, ob. 1256.

Close by is a fresco of Dante expounding his “Divina Commedia,” painted, when the church was used for lectures on that subject, by Domenico di Michelino, a pupil of Fra Angelico, in 1465. The inscription by Politian was added in 1470.

Dante, dressed in a red robe, holding his book open, is at the base of Florence’s walls, whose gates are closed to him. Nearby, we see the entrance to the infernal chasms; Dante points to them with his hand and seems to be saying to his enemies: You see the place I have. But there is more pain than threat on his face as he bends sadly. Revenge does not console him for exile. Further on rises the mountain of purgatory with its circular ramps, and at the top the tree of life of earthly paradise. Paradise is designated by somewhat indistinct circles that surround the entire composition. Dante is there with his work and his destiny. This curious representation dates from 1450. Its author was a monk who then explained the Divine Comedy in the cathedral. Thus, one hundred and thirty years after the death of Dante, a public lesson was given on his poem in the cathedral, and the image of the poet was hung on the walls of the church beside those of the prophets and saints.

Jean-Jacques Ampère, La Grèce, Rome & Dante Études, p. 236.

Giorgio Vasari, The Last Judgment, 1572-79 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The wooden urn above the next door is that of Don Pedro of Toledo, the great Viceroy of Naples (1553), and father of the Grand-Duchess Eleanora, who was rumoured to have been poisoned by his son-in-law, Cosimo I. Beyond this are a modern monument with a bust to the architect, Arnolfo di Cambio; a statue of the scholar, Poggio Bracciolini, by Donatello; and the monument of Antonio Squarcialupo, the musical composer and organist, with a bust by Benedetto da Majano. Against the column opposite this monument is a picture of S. Zenobio, seated between S. Crescenzio and S. Eugenio, who kneel on either side.

The fresco of the cupola was begun by Giorgio Vasari, and finished by Federigo Zucchero (1579).

We cannot visit the Cathedral without recalling the scenes which took place here during the preaching of Savonarola in the great “revival” of the fifteenth century.

Savonarola Preaching. Woodcut from Girolamo Savonarola, “Compendio di revelatione / dello invtile servo di Iesv Christo frate Hieronymo da Ferrara dellordine de Frati Predicatori” Florence, 1496. Note the curtain separating male from female worshipers.

The people got up in the middle of the night to get places for the sermon, and came to the door of the cathedral, waiting outside till it should be opened, making no account of any inconvenience, neither of the cold nor the wind, nor of standing in winter with their feet on the marble; and among them were young and old, women and children, of every sort, who came with such jubilee and rejoicing that it was bewildering to hear them, going to the sermon as to a wedding. Then the silence was great in the church, each one going to his place; and he who could read, with a taper in his hand, read the service and other prayers. And though many thousand people were thus collected together, no sound was to be heard, not even a “hush,” until the arrival of the children, who sang hymns with so much sweetness that heaven seemed to have opened. Thus they waited three or four hours till the Padre entered the pulpit, and the attention of so great a mass of people, all with eyes and ears intent upon the preacher, was wonderful; they listened so, that when the sermon reached its end it seemed to them that it had scarcely begun.

Fra Pacifico Burlamacchi, La Vita Savonarola, pp. 85–86.

The beauty of the past in Florence is like the beauty of the great Duomo.

About the Duomo there is stir and strife at all times; crowds come and go; men buy and sell; lads laugh and fight; piles of fruit blaze gold and crimson; metal pails clash down on the stone with shrillest clangour; on the steps boys play at dominoes, and women give their children food, and merry-makers join in carnival fooleries; but there in the midst is the Duomo all unharmed and undegraded, a poem and a prayer in one, its marbles shining in the upper air, a thing so majestic in its strength, and yet so human in its tenderness, that nothing can assail and nothing equal it.

Ouida, Pascarèl, vol. 1, p. 241.

S. Giovanni (S. John Baptist), “the Baptistery of my gracious St. John,” as Dante calls it, was once the cathedral. Its age is uncertain, but probably dates from the fifth or sixth century, when octagonal structures had become popular in the Christian world. It may well occupy the site of a temple of Mars, as says tradition. Pope Nicholas II consecrated the Baptistery in 1059.

San Giovanni (Baptistery), 11th c. (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Externally the Romanesque style Baptistery is a green and white octagonal building in three sections, with a pyramidal roof and lantern. The green marble was quarried at Prato and the white at Carrara. As we look at it further, we become aware that this peculiar Florentine green and white decoration has its origin in architectural spacing. Here and there are seen a set of pretended blocks, lined out; and here and there pretended relief arcading even as our northern gothic architects and masons, in the best periods, used artificial painted lines, even over their finest masonry. Here, however, it is designed methodically to accommodate the division of each facet of the octagon into three bays. On the ground storey each facet aforesaid is marked by flat pilasters which, continued into the second section, terminate in round green and white arches, containing alternately round-headed and square windows. On the third section or storey, flat fluted pilasters, corinthian, carry up the surface, enclosing rectangular panels of white marble in green marble frames. Flanking the Eastern door (facing the Duomo) are two mended ancient porphyry columns. Others, of granite, flank the other entrances. The whole effect is striking, but not at first fascinating. It is a speciality of Florence, full of character and originality. Time has given it poetry.

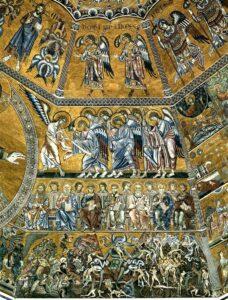

Baptistery Vault NE section, 1240-1300 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Baptistery vault. The vault is undergoing cleaning in 2023. (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Baptistery Vault, NW section, 1240-1300 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Within, although there is plenty of “correspondence,” no one, however skilful, could predict from given external features the interior effects. Rising from a floor of broad-panelled mosaic, each facet of the octagonis divided up into the three bays corresponding to the exterior ones by granite columns having gilded caps. Compound fluted pilasters fill the angles, excepting on the west side, where the original portico has been blocked up and converted, for placing the high altar and choir, into a deep rectangular recess crowned by a bold mosaic-inlaid arch, which invades the second storey with grand effect. On the opposite side (E.) the interruption is caused by the insertion of the organ-gallery.

On the northwest side of the basement, between two granite columns, is placed beneath a graceful gilded canopy the splendid tomb of Pope John XXIII., and above it hangs a cardinal’s hat. On the opposite side of the choir is a statue of S. John the Baptist, in front of which is placed the font, so continually in use. The upper storey, above a rich mosaic frieze and marble cornice, consists of a gallery masked by an arcade of three in each facet of the building, whereof each arch is bifurcate. These coupled arches rise from a dado decorated with rectangular mosaic panels, containing apostles, prophets, and saints. This gallery, communicating from facet to facet, is lit by small splayed windows. It is succeeded by a frieze of mosaic and cornice, as before, carrying a second clear storey, which supports the dome. The latter is covered with mosaic and crowned with a lantern, though originally it was open, like the Pantheon at Rome.

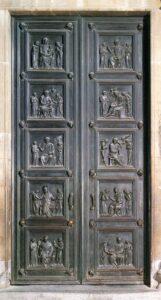

Andrea Pisano. South Gates, 1330 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

It is entered on the S. by the glorious Gates of Andrea Pisano, executed in 1330. [Original gates are now in the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo.] Of their twenty large panels appropriately representing scenes in the life of the Baptist, the two most beautiful are those of Zacharias naming his son, and of S. John being laid in the tomb by his disciples.

Andrea Pisano, S. John being laid in the tomb by his disciples, 1330 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Andrea Pisano, Zacharias naming his son, 1330 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

In the first, Zacharias is represented as a venerable old man, writing at a table, near which stand a youth and two women, beautifully draped, and grouped into a composition whose antique simplicity of means shows how far Andrea had advanced beyond Niccola and Giovanni (Pisano), who could not tell a story without bringing in a crowd of figures. In the Burial of S. John we see a sarcophagus, placed beneath a gothic canopy, into which five disciples are lowering the dead body of their master, two at the shoulders (one of whom evidently sustains the whole weight of the corpse), and two at the feet, while a sorrowing youth holds up a portion of the winding-sheet; a monk, bearing a torch, looks down upon the face of S. John from the other side of the Area, and near him stands an old man, his hands clasped in prayer and his eyes raised to heaven. In these works we find sentiment, simplicity, purity of design, and great elegance of drapery, combined with a technical perfection hardly ever surpassed, while the single allegorical figures show the all-pervading influence of Giotto, from whom Andrea learned to use the mythical and spiritual elements of German art, as Giovanni Pisano had used the fantastic and dramatic. When they were completed and set up in the doorway of the Baptistery, now occupied by Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise, all Florence crowded to see them; and the Signory, who never quitted the Palazzo Vecchio in a body except on the most solemn occasions, came in state to applaud the artist, and to confer upon him the dignity of citizenship.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, pp. 65–66.

Scarcely less beautiful are the N. Gates, of 1401, by Lorenzo Ghiberti.7Son of Cione di Ser Buonacorso di Abatino di Ghiberti. Born in 1378, he sat amongst the twelve Buonuomini in 1443, and amongst the sixteen Gonfalonieri in 1446. He bought a fine estate near Badia a Settimo, and had a house in Borgo Allegri, where he died in 1455. depicting twenty subjects from the New Testament inclosed in a marvellous frieze of foliage, fruit, and birds. Copies of the doors have replaced the originals which are housed in Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo.

Lorenzo Ghiberti, North Doors, 1401-25 (photo Web Gallery of Art)

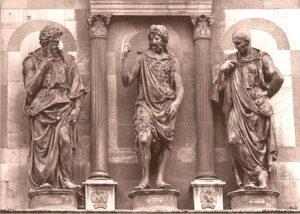

The northern gate is the result of that famous competition which opened the Quattro-cento. It was assigned to Lorenzo Ghiberti in 1403, and he had with him his stepfather, Bartolo di Michele, and other assistants (including, possibly, Donatello). It was finished and set up, gilded, in April 1424, at the main entry between the two porphyry columns opposite the Duomo, whence Andrea Pisano’s gate was removed. It will be observed that each new gate was first put in this place of honour, and then translated to make room for its better. The plan of Ghiberti’s is similar to that of Andrea’s gate—in fact, it is his style of work brought to its ultimate perfection. Twenty-eight reliefs represent scenes from the New Testament, from the Annunciation to the Descent of the Holy Spirit; while in eight lower compartments are the four Evangelists and the four great Latin doctors. The scene of the Temptation of the Saviour is particularly striking, and the figure of the Evangelist, John, the Eagle of Christ, has the utmost grandeur. Over the door are three finely modelled figures, representing S. John the Baptist disputing with a Levite and a Pharisee—or perhaps the Baptist between two prophets—by Giovanni Francesco Rustici (1506–1511), a pupil of Verocchio, who appears to have been influenced by Leonardo da Vinci.

Edmund G. Gardner, Story of Florence, pp. 255–56.

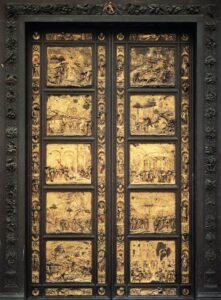

The E. Gates were executed by the same artist, 1447–1452. [The original gates, now in the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo, were replaced with copies in 1990.] It was of these that Michelangelo said that they “were worthy to be the gates of Paradise.” The ten compartments represent subjects from the Old Testament. The head in the centre is said to be the artist’s portrait, and that next to it, Bartolo, his stepfather. The inscription is near them “Laurentii Cionis de Ghibertis mira arte fabricatum.” [Crafted by the wonderful art of Lorenzo Cioni of the Ghiberti.]

“In modelling these reliefs,” says Ghiberti, in his second Commentary, “I strove to imitate Nature to the utmost, and by investigating her methods of work to see how nearly I could approach her. I sought to understand how forms strike upon the eye, and how the theoretic part of sculptural and pictorial art should be managed. Working with the utmost diligence and care, I introduced into some of my compositions as many as a hundred figures, which I modelled upon different planes, so that those nearest the eye might appear larger, and those more remote smaller in proportion.”

Lorenzo Ghiberti, 2nd Commentary.

The work lasted forty years, says Vasari, that is to say one year less than Masaccio had lived, one year more than Raphael was to live. Lorenzo, who had begun it full of youth and strength, finished it old and bent. His portrait is that of that bald old man who, when the door is closed, stands in the ornament in the middle; A whole artist’s life had passed in sweat, and had fallen drop by drop on this bronze!

Alexandre Dumas, Une année à Florence, p. 219.

Each of the gates is surmounted by copies of a group in bronze,8The originals are displayed in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo. viz.: —

Giov. Franc. Rustici, St John the Baptist Preaching, 1506-11 (Northern Gate) (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Andrea da Sansovino, Baptism of Christ, 1502-05 (Eastern Gate) (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Vincenzo Danti, Beheading of St John the Baptist, 1569-71 (Southern Gate) (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The detached porphyry columns near the eastern gates were a gift from Pisa in gratitude for the protection afforded by Florence in 1114.

The Interior of “San Giovanni” is very dark, even when empty. It is surrounded by sixteen columns, of which fifteen are of grey granite and one of white marble—the last believed to be the column on which the statue of Mars stood near Ponte Vecchio, and at the foot of which Buondelmonte fell, murdered by the Amidei. The cupola is covered with mosaics, having a huge figure of Christ in the centre, surrounded by “Angels, Thrones, Dominations, and Powers.” Tuscan mothers take their children propitiously to the ancient and gloomy building. The silence is full of joy; nor does the priest partake of the solemnity. None of the three look up to see or heed the dingy mosaics displaying the ghastly scenes of retribution.9The mosaics are undergoing cleaning in 2023. The latter, in fact, have faded with age, as are now doing with advancing enlightenment the credulous ideas which suggested their representation. The mosaic of the Tribune is by Jacopo Turrita, author of the famous mosaic in the Lateran at Rome. The high-altar had a beautiful frontal of silver repoussé work, now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo.

The present font replaces one brought from S. Reparata in 1128, which was destroyed in 1576 by order of Grand Duke Francesco I. This was a large basin for immersion, surrounded by smaller basins, one of which was broken by Dante while saving a child from drowning. Speaking of the holes in which sinners guilty of simony are punished, he says: —

Non mi parien meno ampi nè maggiori

Che quei che son nel mio bel San Giovanni

Fatti per luogo de’ battezzatori;

L’ un degli quali, ancor non è molt’ anni,

Rupp’ io per un che dentro vi annegava:

E questo sia suggel ch’ ogni uomo sganni.

To me less ample seemed they not, nor greater

Than those that in my beautiful Saint John

Are fashioned for the place of the baptisers,

And one of which, not many years ago,

I broke for some one, who was drowning in it;

Be this a seal all men to undeceive.

Dante Inferno 19:16–20. Trans. Longfellow.

In years past all the children born in Florence were baptized in the present font.

The beautiful tomb of John XXIII. (Baldassare Cossa) is by Donatello and his pupil Michelozzo Michelozzi. After John was deposed by the Council of Constance, he came to Florence to humble himself to his successful rival, Martin V., and died here in 1417 in the Palazzo Orlandini. He was honoured with a magnificent funeral, for which he had left funds. He had provided for his tomb by his will. Pope Martin (Colonna) residing at S. Maria Novella, objected to the words “Quondam Papa” [former Pope] in the epitaph, and desired Cosimo de’ Medici to alter them, but he proudly declined in the words of Pilate, “Quod scripsi, scripsi.” [What I have written, I have written] A tomb, with a gothic inscription, on the left of this, commemorates Ranieri, Bishop of Florence.

This monument is curious as the subject of a Florentine tradition. A woman who made a fortune by the sale of vegetables, and was known in Florentine dialect as the “Cavajola” (cabbagewife), bequeathed money to have the bells of Ogni Santi and the Cathedral annually rung from the 1st of November to the last day of Carnival for the repose of her soul. Her memory is held in much respect by her townspeople, who believed that in some unaccountable manner her bones rest in the sarcophagus of Bishop Ranieri, whose tomb has therefore been called La Tomba della Cavajola.

Susan & Joanna Horner, Walks in Florence, vol. 1, p. 40.

A Roman sarcophagus near the font is a relic of many of the kind which once stood on the outside of the building, around which Guido Cavalcante used to muse, and which were removed c. 1292.

Jacopo Bellini was forced to do public penance in the Baptistery (April 8, 1425) for thrashing one Bernardo di Ser Silvestri, who had thrown stones into his studio.

The interior of the Baptistery has a charm of solemnity, almost of sadness, like some old mother brooding over generations of her children who have passed away—old, old, meditative still, lost in a deep and silent mournfulness. The great round of the walls, so unimpressive outside, has within a severe and lofty grandeur. The vast walls rise up dimly in that twilight coolness which is so grateful in a warm country—the vast roof tapers yet farther up, with one cold pale star of light in the centre; a few figures, dwarfed by its greatness, stand like ghosts about the pavement below—one or two kneeling in the deep stillness; while outside all is light and sound in the piazza, and through the opposite doors a white space of sunny pavement appears dazzling and blazing.

Blackwood, DCCV.

On Thursday before Easter a feast of candles seems to be held in every church, and crowds stream in and out all day. At the doors, outside, sit sellers of these hazel and willow wands, which are twined about with thin strips of blue and red paper. As they are already denuded of bark, they become thus red, white, and blue. The children eagerly purchase them, and, going into church thus weaponed, they beat the pavements with them. The rods symbolise the scourges with which Christ was scourged; and the three colours his innocent flesh and the blood and bruises inflicted upon it. The children, however, are supposed to be flogging Judas. It is not a little naïve that children should thus come to be afforded amusement in remembrance of the sufferings of their best Friend. Depend upon it, many a small brother or sister cries at that game before night. But after all it may go back farther and be but another pagan custom, the meaning of which is obscured, transferred, and adapted to Christian usage.

The Piazza del Duomo contains several points of interest in Florentine history. The alley which leads from the piazza, behind the Misericordia, to the Via Calzaioli, records in its name of Via della Morte a curious story which is told by Boccaccio.10Not in the Decameron. Perhaps elsewhere.—Ed.

Antonio Rondinelli, having fallen in love with Ginevra degli Amieri, could not by any means obtain her from her father, who preferred to give her to Francesco Agolanti, because he was of noble family. The grief of Rondinelli cannot be described, but it was equalled by that of Ginevra, who could never be reconciled to the marriage which was arranged for her. Whether, therefore, from a struggle with hopeless love, or from hysteria, or some other cause, it is a fact that, after this ill-assorted marriage had lasted for four years, Ginevra fell into an unconscious state, and, after remaining without pulse or sign of life for some time, was believed to be dead, and as such was buried in the family tomb in the cemetery of the Duomo near the Campanile. The death of Ginevra, however, was not real, but an appearance produced by catalepsy. The night after her interment she returned to consciousness, and, perceiving what had happened, contrived to unfasten her hands, and crept as well as she could up the little steps of the vault, and, having lifted the stone, came forth. Then, by the shortest way, called Via della Morta from this circumstance, she went to her husband’s house in the Corso degli Adimari; but, not being received by him, who from her feeble voice and white dress believed her to be a spectre, she went to the house of Bernardo Amieri, her father, who lived in the Mercato Vecchio behind S. Andrea, and then to that of an uncle who lived close by, where she received the same repulse.

Giving in to her unhappy fate, it is said that she then took refuge under the loggia of S. Bartolommeo in the Via Calzaioli, where, while praying that death would put an end to her misery, she remembered her beloved Rondinelli, who had always proved faithful to her. To him she found her way, was kindly received and cared for, and in a few days restored to her former health.

Up to this point the story has nothing incompatible with truth, but that which is difficult to believe is the second marriage of Ginevra with Antonio Rondinelli, while her first husband was still living, and her petition to the Ecclesiastical Tribunals, who decided, that the first marriage having been dissolved by death, the lady might legitimately accept another husband.[mfnThis story is known in France by the poem of Scribe, “Guido et Ginevra.” See also The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, ed. Harry Buxton Forman, vol. 4, London, 1882, pp. 545–48.[/mfn]

Marco Lastri, L’Osservatore Fiorentino sugli edifizj della sua patria, 3rd ed., vol. 1, Florence, 1821, p. 119–22.

The next side-street, Via dello Studio, contains the Collegio Eugeniano, founded for chorister-boys by Pope Eugenius IV. in 1435. At the corner of this street an inscription marks the birthplace of Beato S. Antonino (1389–1459).

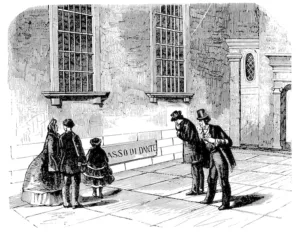

19th c. tourists visiting Dante’s stone. (photo via Curiousrambler)

Close by, on the south of the piazza, in front of the House of the Canons, are modern statues of its two architects, Arnolfo di Cambio and Brunelleschi, by Pampaloni (1830).

Farther down the piazza, on the same side, is the stone inscribed “Sasso di Dante” ([Dante’s stone] now let into the wall), where Dante is said to have sat and gazed at the cathedral. Other stones claim the honor of having served the poet.

On the stone

Called Dante’s, —a plain flat stone scarce discerned

From others in the pavement whereupon

He used to bring his quiet chair out, turned

To Brunelleschi’s church, and pour alone

The lava of his spirit when it burned:

It is not cold to-day. O passionate

Poor Dante, who, a banished Florentine,

Didst sit austere at banquets of the great

And muse upon this far-off stone of thine,

And think how oft a passer used to wait

A moment, in the golden day’s decline,

With “Good-night, dearest Dante”—well, good-night!

I muse now, Dante, and think verily,

Though chapelled in the by-way out of sight,

Ravenna’s bones would thrill with ecstasy,

Couldst know thy favourite stone’s elected right

As tryst-place for thy Tuscans to foresee

Their earliest chartas from.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Casa Guidi Windows, Part 1:15.

All around the northern side of the Duomo are old palaces, having arcaded rustic basements, once belonging to the Berardi and the former Opera del Duomo.

At the eastern angle of the piazza, is a palace marked by a bust of Cosimo I., which was at one time the residence of Lorenzo de’ Medici. At 21 Via dei Servi, lived and worked Donatello.

An archway close to this palace leads to the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo or Museo di S. Maria del Fiore, which contains a most interesting collection of objects and fragments connected with the church. Founded in 1891, the Museo was completely renovated and the collection reinstalled in 2015. The result is nothing short of spectacular.