4.1: The Badia, Bargello, and Vicinity

Returning to the Via del Proconsolo and turning to the left, we reach, on the right, La Badia (di San Stefano) presents a façade which, though unfinished, never would or could have been beautiful. It is now full of shops. The Church is entered by a rich door to the right through a passage. It was founded by Willa, wife of the Marquis of Tuscany, in 993, for the Black Benedictines. She presented the Abbot with a knife, to show that he might curtail or dispose of the property at his pleasure; the staff of pastoral authority: a branch of a tree as lord of the soil; a glove, the sign of investiture; and finally caused herself to be expelled to prove that she resigned all her former rights. The abbey was greatly enriched by her son Ugo, who was governor of Tuscany for Otto III. Losing his way in a forest near Buonsollazzo, he had a hideous vision of human souls tormented by devils, and selling his property, he endowed therewith seven religious houses, in expiation of the seven deadly sins. Ugo is annually commemorated on S. Thomas’s Day, when, till lately, some noble young Florentine has always declaimed his praises during the celebration of Mass. Dante alludes to this custom:

Ciascun che della bella insegna porta

Del gran barone, il cui nome e ‘l cui pregio

La festa di Tommaso riconforta.

Each one that bears the beautiful escutcheon

Of the great baron whose renown and name

The festival of Thomas keepeth fresh,

Dante Paradiso 16:127–29. Trans. Longfellow.

Badia Campanile (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The existing abbey was built by Arnolfo di Lapo in 1250, but much altered by Segaloni in 1625. The present graceful bell-tower was built in 1320, the original campanile having been pulled down as a punishment to the Abbot, because he refused to pay his taxes, and rang the bells to summon the Florentine nobles to support him. Later in the same century Boccaccio here gave his famous lectures on Dante (1373). The door, of 1495, was erected by Benedetto da Rovezzano, at the expense of the Pandolfini, whose family burial-place is here.

The Church, in the form of a Greek cross, once contained many frescoes by Giotto and Masaccio, which have been destroyed, but it is still interesting for its tombs. On the right of the entrance, under a delicately sculptured arch, with a deeply coffered vault, is the sarcophagus of Gianozzo Pandolfini, 1456, the statesman who secured the treaty of peace between Florence and Alfonso of Naples. Close by is an altar with beautiful reliefs by Benedetto da Majano (1442–97). In the north transept is an exquisite tomb by Mino da Fiesole to Bernardo Giugni, a famous Guelfic Gonfalonier, who died in 1466.

Mino da Fiesole, Tomb of Bernardo Giugni, 1468 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Mino da Fiesole, Tomb of Ugo, 1481 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The figure of Justice on this tomb [Giugni]is meagre in outline, though refined in conception and workmanship. The best testimony to the virtues of the occupant of this tomb, who served Florence as ambassador on several important occasions, and was made Cavaliere and Gonfaloniere, is contained in these words of his biographer:1Vespasiano Bisticci, Arch. St. It., iv. “Beato alla città di Firenze, se avesse avuto simili cittadini.” [Blessed the city of Florence if it had such citizens.]

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, pp. 210–211.

In the east wall is the tomb of the quasi-founder, erected by the monks in 1481 to Ugo, Marquess of Tuscany, who died in 1006.

The architectural features of Count Ugo’s monument are, like those of the finest Tuscan tombs, an arched recess, within which is placed the recumbent statue upon a sarcophagus; a charming Madonna and Child in relief in the lunette, below which is a figure of Charity, somewhat too long in its proportions; flying angels with a memorial tablet, two genii bearing shields, and an architrave sculptured with festoons and shells in low relief, compose its sculptured features.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, p. 210.

Above this tomb (which is sometimes attributed to Mino da Fiesole, and sometimes to Rossellino) is an Assumption by G. Vasari. On the left of this transept is the Chapel of the Bianchi, containing the Apparition of the Virgin to S. Bernard as he writes in a rocky landscape near his convent, the best easel picture of Filippino Lippi. It was painted in 1480 by order of Francesco del Pugliese for the church at La Camfora outside the walls, and was removed hither for safety during the siege of Florence in 1529. The donor is represented on the right, white Cistercians are seen in the background, and two in black and white, to mark the change to white only which took place in their habit after this traditional episode.

Filippino was a naturalistic painter; but he was without scandal and by happily choosing his models, as can be seen in the charming painting of the Badia, which he painted at the age of twenty (1480) and of which all the figures are family portraits. Saint Bernard is the main character, and the Virgin who appears to him, and the angels with whom she is accompanied, are quite simply a mother surrounded by her children; but what a mother and what children!

Alexis-François Rio, L’ art chrétien, vol. 1, p. 392.

There is a double cloister, with a well, and many ruined frescoes in the upper storey, telling the history of S. Benedict and Subiaco, by Niccolò d’ Alunno.

Near the entrance is the tomb of the ill-fated Francesco Valori, the friend of Savonarola, who perished in the riot when S. Marco was besieged.

Tomb of Francesco Valori (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Finding that scarcely a feeble resistance was made within S. Marco, whilst the enemy without were hourly increasing in number and force, Francesco Valori was desirous of getting to his own house, in order to collect his adherents, and make a more energetic defence from without. But his dwelling-place was suddenly surrounded by a great number of persons, and a mace-bearer arrived from the Signory requiring him to appear immediately before them. He showed every desire to obey, feeling sure that he should be able, by his presence and authority, to make them ashamed of their conduct; he therefore set out immediately with the mace-bearer for the Palazzo. He passed through the crowd with a lofty air and serene countenance, like a man confident in his innocence, and who had never flinched before any danger. But they had scarcely reached the Church of S. Proculo when they were met by some members of the Ridolfi and Tornabuoni families, relations of those of whose condemnation to death in the preceding August he had been the cause, and they at once attacked and killed him. In this way a public injury met reparation by private revenge; and thus a valiant and honest citizen, who had always been the most powerful friend of Savonarola, perished miserably. His wife, hearing the noise, ran to the window in terror, and in the midst of the confusion and frightful cries of her husband and his murderers, a shot from a cross-bow amongst the crowd sent her to be united to him in a better world. The maddened populace immediately entered, sacked, and set fire to the house; and while they were carrying off the furniture of a bed, a baby that was asleep in it, a grandson of Valori, was suffocated. The Signory neither then nor afterwards made any inquiry into these murders and outrages.

Pasquale Villari, History of Savonarola, vol. 2, pp. 296–297.

The beautiful Campanile is best seen from the tiny Piazza dei Guochi behind the houses on the west.

In the garden is a statue of Ugo, whom Dante styles “the great Baron.” [Paradiso 16:128.]

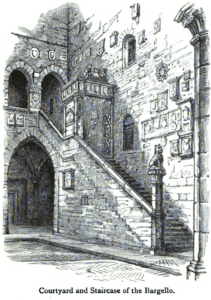

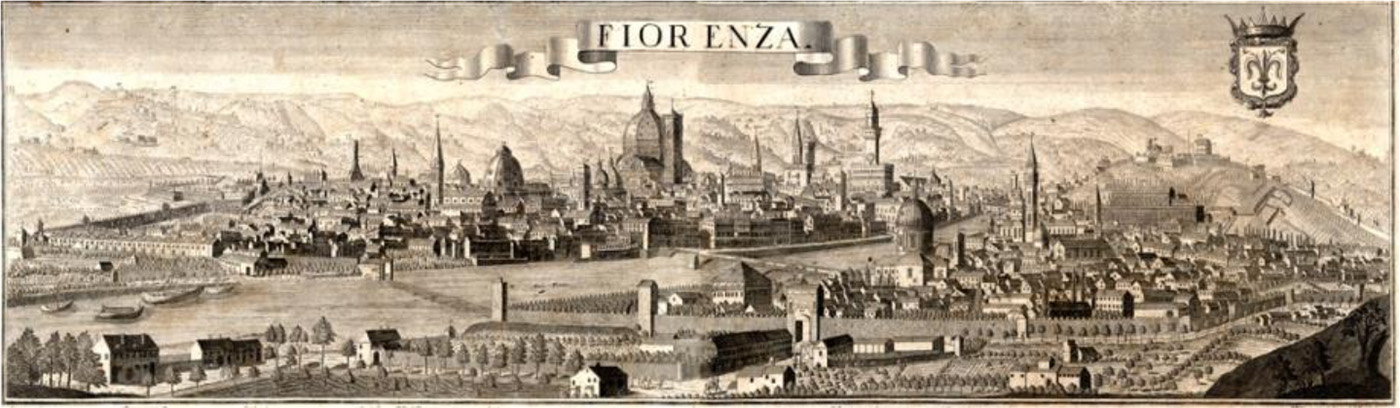

Opposite the Badia rises in three storeys crowned with square battlements the massive Bargello, built as the Palace of the Podestà, the chief criminal magistrate of Florence. According to a law enacted when the office was created in 1199, the Podestà must always be a foreigner, a noble, a Catholic, and a Guelf. But in 1250 a Ghibelline named Ranieri da Montemurlo was elected, which caused an insurrection of the people, who chose a new governor, and fortified the old tower of the Boscoli Palace with the adjoining buildings as his residence. The latter was succeeded by Guido Novello, Viceroy to Manfred, 1260–66, during whose time much of the present building was erected, perhaps, as Vasari says, by Lapo. The chief power continued in the hands of the Podestà till 1462, when it was restrained by a tribunal called (from the round stones—ruote—which paved the hall in which they held their meetings) Giudici alla Ruota. The office of Podestà was finally abolished by Cosimo I., when the palace-castle was assigned to the Bargello or head of the police.

The greater part of the palace is due to Arnolfo di Lapo. Upon the outside of the older tower, facing the Via del Palagio, were painted mock frescoes of the Duke of Athens and his associates, hanging, but they are no longer visible. The bell within, called the Montanara, obtained the name of La Campana del Armi, because it was the signal for citizens to lay aside their weapons and retire home.

The street below the Bargello witnessed, August 1, 1343, one of the most violent scenes of Florentine history. The Duke of Athens had taken refuge in the fortress, and the members of the noble Florentine families, Medici, Rucellai, and others, who had suffered from his tyranny, were besieging him. They demanded, as the price of his life, that the Conservatore Guglielmo d’Assisi and his son, a boy of eighteen, who had been the instruments of his cruelty, should be given up to them. Forced by hunger, the Duke caused them to be pushed out of the half-closed door to the populace, who tore them limb from limb, hacking the boy to pieces first before his father’s eyes, and then parading the bloody fragments on their lances through the streets.

Many and many a last sigh has been heard unheeded here; many a gentle, as well as many a brutal, face has gazed its last look on Heaven into that pale square of Florentine sky, wondered a moment, and—died.

Unattributed

The Bargello, restored in 1865, now used as the Museo Nazionale, has undergone numerous changes since Florence was last published in 1925. Works have been reinstalled in different galleries or moved to storage. New acquisitions have added to the collection and old favourites have been demoted. Curatorial practice is ever evolving, never constant. The placement of works described below is a snapshot of the early 2020s and will likely become superannuated with the passage of time. Since the flood of 1966, the Bargello is entered from Volognana Tower. Previously one entered from the Via del Proconsolo, through two halls full of arms. The colonnaded court is intensely picturesque and most rich and effective in colour; its staircase was built by Agnolo Gaddi. Near the Well in the centre many noble Florentines have been beheaded, including (1530) Niccolò de’ Lapi, the hero of Massimo d’ Azeglio’s novel [Niccolò dei Lapi (1841)]. The scaffold, with all its tragic appurtenances, was burned in 1782 by the order of Duke Pietro Leopoldo. The arms of the Duke of Athens hang near the entrance, followed by those of the two hundred and four Podestàs who ruled afterwards in Florence. Ground Floor: The cortile (courtyard) is surrounded by vaulted arcades under which are:— North Side:

East Side:

Bartolomeo Ammannati, Juno Fountain, 1556–61 (photo source)

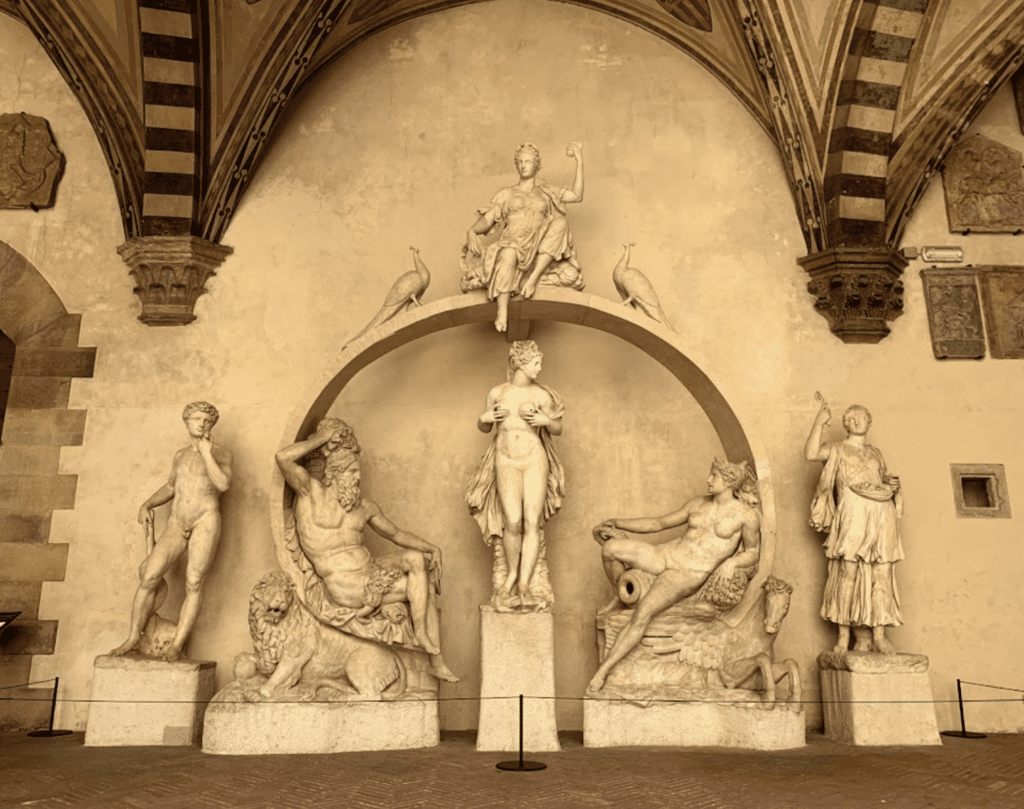

Bartolomeo Ammannati. A monumental allegorical fountain, 1556–61, from the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio. Figures include Juno between two peacocks, Ceres, from whose breasts the water flows, the River Arno, the font of Mount Parnassus, a youth, and Flora, goddess of flowers. South Side:

Giovanni da Bologna, Oceanus, 1576, from the Boboli Gardens Isoloto (Island) (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Vincenzo Danti, Cosimo I. as a Roman Emperor, 1568–72

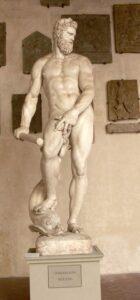

Michelangelo, Bacchus, c. 1497 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Giovanni Bandini (Giovanni del Opera). Bacchus, 1570s (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

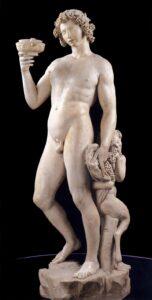

Jacopo Sansovino, Bacchus, 1512. (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

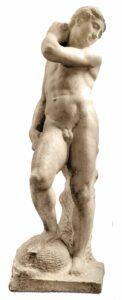

Michelangelo, David/Apollo, 1530 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Michelagnolo, to make a friend of Baccio Valori;, commenced a figure in marble of three braccia high; an Apollo namely, drawing an arrow from his quiver, but did not quite finish it; it is now in the apartments of the Prince of Florence, and although, as I have said, not entirely finished, is a work of extraordinary merit.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 4, p. 128.

Michelangelo, Madonna and Child [Pitti Tondo], c. 1503–05 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Michelangelo, Marcus Brutus (unfinished), 1546-50 (photo Web Gallery of Art)

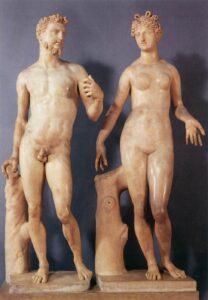

Baccio Bandinelli, Adam and Eve, 1549–51 (photo Web Gallery of Art)

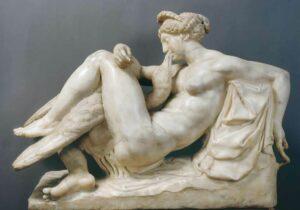

Bartolommeo Ammanati, Leda and the Swan, 1540s (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

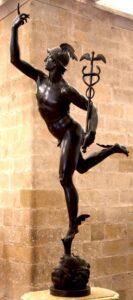

Giovanni da Bologna. Mercury, executed1598 OR 1580 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Who does not know the Mercury of Gian Bologna, that airy youth with winged feet and cap, who, with the caduceus in his hand, and borne aloft upon a head of Aeolus, seems bound upon some Jove-commissioned errand? Who has not admired its lightness and truth of momentary action which none but an artist skilful in modelling and well versed in anatomy could have attained, since, Mercury-like, it has winged its way to the museums and houses of every quarter of the globe?

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 2, p. 173.

The pedestal is almost as worthy of study as the statue it supports.

Its central portion is occupied by the graceful figure of Andromeda, whose long tresses stream in the wind, as, shielding her eyes with her hand, she looks upward for her deliverer, who is coming down from the clouds to attack the monster, who, with open jaws, bat-like wings, claws of iron strength, and scaly body, stands ready to receive him. Upon the shore are Andromeda’s mother, Cassiopeia, and her father Cepheus, who has a stern, sad face; while between them her disappointed lover Phineas, whose head reminds us of an antique gem, rises from the earth like an avenging spirit, followed by a troop of warriors on foot and on horseback, the last of whom gallop furiously through the clouds.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 2, p. 136.

No one thinks of the pedestal when he has once caught sight of the Perseus. It raises the demigod in air; and that suffices for the sculptor’s purpose. Afterwards, when our minds are satiated with the singular conception so intensely realised by the enduring art of bronze, we turn in leisure moments to the base on which the statue rests. Our fancy plays among those masks and cornucopias, those goats and female Satyrs, those little snuff-box deities, and the wayward bas-reliefs beneath them. There is much to amuse, if not to instruct and inspire us there.2The ornaments of the pedestal, perfectly safe, and much valued here, have recently been carried off to the Bargello and replaced by copies.

J. A. Symonds, Life of Cellini, vol. 1, p. lxxvi.

Baccio Bandinelli. Bust of Cosimo I, 1543–44 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Benvenuto Cellini, Bust of Cosimo I. de’ Medici, 1546–47 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The bronze bust by Benvenuto Cellini shows what a potent and valiant man he was; but the world remembers him chiefly by a horrid crime—the murder of his son in the presence of the boy’s mother.

W. D. Howells, Tuscan Cities, pp. 90–91.

The beautiful upper Loggia, or “Il Verone” is attributed to Orcagna: it was once used for the Council of the Magistrates. It now contains a collection of works in bronze by Giov. Da Bologna (1524-1608), including his graceful statue of Architecture on a pedestal with the arms of the Medici by Niccolò Tribolo, an Eagle, a Falcon, and a Turkey.

On the right of the upper Loggia we enter the 1st Hall, now called the Sala di Donatello,3Donato di Niccolò de Betto Bardi, called Donatello from his small stature. He was born 1386, died 1466, at his house in the Via del Cocomero, and is buried near the Medici in S. Lorenzo. magnificent in itself, and occupied by the works of Donatello, or copies of them. During the sixteenth century it was divided up into cells for prisoners.

Donatello, David, 1409 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Donatello, Il Marzocco Florentino, c. 1419 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Desiderio da Settignano, S. John Baptist, 1460s (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

With the exception of Michelangelo, no Tuscan sculptor had so marked an influence as Donatello upon the art of his time. He may, indeed, be called the first and greatest of Christian sculptors, as, despite his great love and close study of classical art, all his works are Christian in subject and in feeling, unless positive imitations of the antique. It is not easy, therefore, to understand why many writers have called Ghiberti a Christian, and Donatello a Pagan, in art. Both loved the antique equally well, and each owed to the study of it his greatest excellence, but certainly no work of Ghiberti can be pointed out so Christian in spirit as the S. George, the S. John, the Magdalen, and many of Donatello’s bas-reliefs. As a man, as well as an artist, he approached far more closely to the ideal of the Christian character, being confessedly humble, charitable, and kind to all around him; a firm friend, and an honest, upright, simple-hearted man. whose fair fame is not marred by a single blot.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, pp. 159–60.

Corona porto, per la patria degna, Acciocchè libertà ciascun antegna.

I bring a crown, for a worthy homeland, So that each man has freedom.

The hair is wonderfully treated, growing in the most natural way from the head, and falling about it in ringlets perfectly graceful in line, and almost silken in quality. The ancients were, indeed, unrivalled in their treatment of hair in the abstract, but no sculptor, ancient or modern, ever surpassed Donatello in giving it all its qualities of growth and waywardness.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, p. 149.

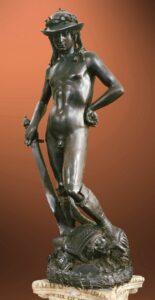

Donatello, David, 1430s (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Verrocchio, David, 1473–75 (photo via nga.gov)

The youthful, undraped head, his face overshadowed by a shepherd’s hat wreathed with ivy, stands with one foot upon the head of his giant enemy, grasping a huge sword in his right hand, and resting his left against his hip. The care bestowed upon the whole work is visible even in the helmet of Goliath, which is adorned with a beautiful stiacciato relief of children dragging a triumphal car.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, p. 150.

Verocchio’s David, a lad of some seventeen years, has the lean, veined arms of a stone-hewer or gold-beater. As a faithful portrait of the first Florentine prentice who came to hand, this statue might have merit but for the awkward cuirass and kilt that partly drape the figure.

J. A. Symonds, Renaissance in Italy: Fine Arts, p. 142.

Though deficient in sentiment, it is full of life and animation. The face is very like those of Leonardo in type, the head is covered with clustering curls, and a light corselet protects the body. The left hand, which is very carefully studied, rests upon the hip, while the right grasps a sword, with which the young hero is about to cut off the head of his fallen enemy. Meagre in outline and poor in its forms, it is nevertheless a work of much merit.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, p. 177.

Donatello, Saint George, 1416 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Upon his shield the bloodie cross was scored,

For sovereign help which in his need he had.

Right faithful, true he was, in deed and word;

But of his cheere did seem too solemn sad;

Yet nothing did he dread, but ever was ydrad.

Quoted by Anna Jameson, Sacred Art, vol. 2, p. 404.

Saint George is the chivalrous type par excellence, both liberator and missionary, administering baptism after the delivery, and not sighing after other glories nor after other crowns than that of martyrdom. Saint George seems to be meditating or restraining a momentum, and his delicate and firm hand, so beautifully drawn on his shield, completes the idea his slender and “slung” forms convey of his exquisite organization. Donatello, who had seen so many of the ancient statues, had the merit not to be inspired or dominated by any reminiscence in the production of this incomparable work.

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, vol. 1, p. 289.

Donatello, Predella, Saint George and the Dragon, c. 1416 (photo Web Gallery of Art)

On the pedestal which supports the tabernacle enclosing the figure, the story of St. George killing the dragon is executed in basso-rilievo, and also in marble: in this work there is a horse, which has been highly celebrated and much admired.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 1, p. 313.

Donatello. Coloured terra-cotta bust of Niccolò da Uzzano, 1430s (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Maso degli Albizzi, the ruling spirit of the commonwealth, died in 1417. He was succeeded in the government by his old friend, Niccolò da Uzzano, a man of great eloquence and wisdom, whose single word swayed the councils of the people as he listed.

J. A. Symonds, Sketches and Studies in Italy, p. 131.

As we look at the model of Ghiberti side by side with that of Brunelleschi, we cannot understand how the judges could have hesitated between them, for while Ghiberti’s is distinguished by clearness of narration, grace of line, and repose, Brunelleschi’s is melodramatically conceived and awkwardly composed. In Ghiberti’s Abraham we see a father who, while preparing to obey the Divine command, still hopes for a respite, and in his Isaac a submissive victim; the angel who points out the ram caught in a thicket, which Abraham could not otherwise and does not yet see, sets us at rest about the conclusion; while the servants, with the ass which brought the faggots for the sacrifice, are so skillfully placed as to enter into the composition without attracting our attention from the principal group. Brunelleschi’s Abraham is, on the contrary, a savage zealot, whose knife is already half-buried in the throat of his writhing victim, and who, in his hot haste, does not heed the ram which is placed directly before him, nor the angel, who seizes his wrist to avert his blow; while the ass and the two servants, each carrying on a separate action, fill up the foreground so obtrusively as to call off the eye from what should be the main point of interest.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, pp. 126–27.

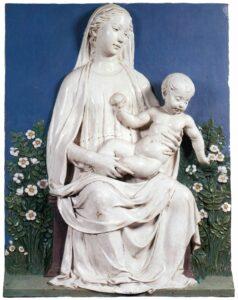

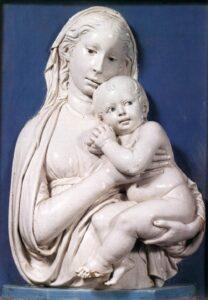

Luca della Robbia, Madonna of the Rose Garden, 1450–55 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Luca della Robbia, Madonna of the Apple, 1455–60 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

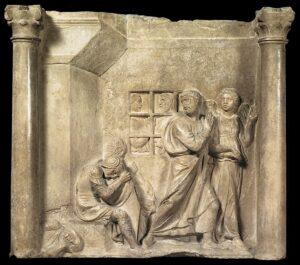

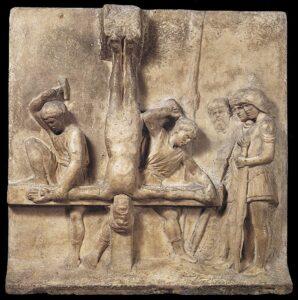

Luca della Robbia, Deliverance of S. Peter from prison, 1439 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Luca della Robbia, Crucifixion of S. Peter, 1439 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The enthusiasm of the Florentines, when this portrait was discovered, resembled that of their ancestors when Borgo Allegri received its name from their rejoicings in sympathy with Cimabue. “L’abbiamo il nostro poeta!” [We have our poet!] was the universal cry, and for days afterwards the Bargello was thronged with a continuous succession of pilgrim visitors. The portrait, though stiff, is amply satisfactory to the admirers of Dante. He stands there full of dignity, in the beauty of his manhood, a pomegranate in his hand, and wearing the graceful falling cap of the day—the upper part of his face smooth, lofty, and ideal, revealing the Paradiso, as the stern, compressed, under-jawed mouth does the Inferno. There can be little doubt, from the prominent position assigned him in the composition, as well as from his personal appearance, that this fresco was painted in, or immediately after, the year 1300, when he was one of the Priors of the Republic, and in the thirty-fifth year of his age—the very epoch, the “mezzo cammin della vita,” [Midway upon the journey of (our) life. Inferno 1:1] at which he dates his vision. In February 1302 he was exiled.

Alexander Lindsay, Christian Art, vol. 2, p. 11.

Arnolfo di Cambio, Three Acolytes, 1265–67 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

One feels that there is something in common between us and the Middle Ages. Their names still exist in their descendants, who often inhabit the very palaces they dwelt in, and their very portraits by the great masters still hang in their halls; whereas we know nothing of the Greeks and Romans but their public deeds, their private life is blank to us.

Mrs. Mary Somerville, Personal Recollections, pp. 261–262.

Andrea della Robbia, Bust of a Boy, c. 1474 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

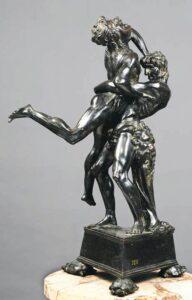

Antonio dei Pollaiuolo, Hercules and Antaeus, c. 1478 (photo Web Gallery of Art)

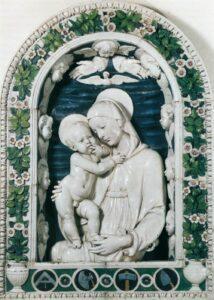

Andrea della Robbia, Madonna of the Architects, 1475 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Andrea Verocchio. Death of Selvaggia di Marco degli Alessandri, c. 1475 [Detail] (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

For some unknown reason it was removed from the Church of S. Maria sopra Minerva (at Rome) and destroyed, with the exception of one bas-relief, representing the death of Selvaggia, who died in child-bed. Around the couch upon which the dying woman sits, supported by her attendants, stand her relatives and friends, one of whom tears her hair in an agony of grief; while another, in striking contrast, crouches in silent despair upon the ground, her head enveloped in the folds of a thick mantle.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, p. 177.

Verocchio, Lady with Primroses, 1475-80 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Francesco Laurana, Bust of Battista Sforza, wife of Federigo da Montefeltro, taken after death, c. 1474 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

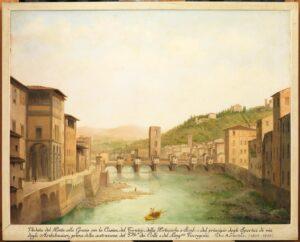

Fabio Borbottoni, Piazza S. Firenze and the Church of S. Apollinare to the right, with the Badia and Bargello behind

Just below the Bargello is the Piazza S. Firenze, at the upper end of which stood the Church of S. Apollinare, where Beccheria, Abbot of Vallombrosa, a leader of the Ghibellines, was beheaded in 1258. Dante places him with Ugolino amongst the traitors in the Inferno:—

Se fossi domandato, altri chi v’ era,

Tu hai dallato quel di Beccheria,

Di cui segò Fiorenza la gorgiera.

If thou shouldst questioned be who else was there,

Thou hast beside thee him of Beccaria,

Of whom the gorget Florence slit asunder.

Dante Inferno 32:118–120. Trans. Longfellow.

San Filippo Neri (S. Firenze), facade (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Baroque Church of S. Firenze, begun in 1645 on the site of a much older one founded in 1174, adjoins the site of the Roman theatre.5Hare found S. Firenze to be “uninteresting.” Pietro da Cortona provided the initial plans, which were modified considerably by Pier Francesco Silvani. The new church, dedicated to San Filippo Neri, was completed in 1715. Ferdinando Ruggieri’s façade consists of a restrained central block and two wings each defined by paired Corinthian pilasters. Sculpture adorns the pediments over the portals. A segmented pediment and attic course complete each wing. The deconsecrated church is now the home of the Franco Zeffirelli International Centre for Performing Arts.

Giuliano di San Gallo, Palazzo Gondi, 1481 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Close by is the Palazzo Gondi (amplified in 1874), built 1481, for Giuliano Gondi, “il Magnifico,” from designs of Giuliano di San Gallo, the splendid chimney-piece of the entrance-hall is also due to him. At the head of the staircase is a fine statue of a Roman Senator, found in excavating for remains of the Temple of Isis. The Gondi family6Arms of Gondi: Or, 2 battle-axes in saltire, sable, tied by a cord, gules. descend from Orlando di Bilicozzo, who sat in the Council of 1197; they fought at Monte Aperti, and have given a gonfaloniere and eighteen priori to the Republic. The Borgo dei Greci leads hence direct to Santa Croce: those especially interested in Florentine history may diverge to the right and visit the Piazza del Grano, with the picturesque loggia for corn-merchants, built 1619 by Cosimo II., whose bust decorates the front.

Palazzo Castellani, now Museo Galileo, c. 1350 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Hence, a narrow street (Via di Leone) leads to the Piazza de’ Castellani, or de’ Giudici, where stood the Castle of Altafronte, afterwards sold to the Castellani. The four-storey building has five bays, rusticated arches on the ground floor, and a loggia, now glazed, on three sides of the top floor. The east façade has a central portone or large portal and no loggia. Between 1841 and 1966 it was the home of the Accademia della Cursa and since 1930 the History of Science Museum. Remodeled in 2010, it is now the Museo Galileo. An inscription on the opposite river-parapet commemorates a horse of the Venetian ambassador killed by a shell in the siege of 1529. Hence, it is only a few steps beside the river to the Ponte alle Grazie. The extreme picturesqueness of the ancient bridge was annihilated in 1874.7The Ponte alla Grazie was destroyed in August 1944. The current bridge, which retains its historic name, was designed by Giovanni Michelucci, Edoardo Detti and others and was built between 1946–53. It was built by Lapo, father of Arnolfo de’ Lapi, in 1237, for Messer Rubaconte da Mandella, a Milanese Podestà.

Come a man destra, per salire al monte

Dove siede la Chiesa, che soggioga

La ben guidata sopra Rubaconte.

As on the right hand, to ascend the mount

Where seated is the church that lordeth it

O’er the well-guided, above Rubaconte.

Dante Purgatorio 12:100–102. Trans. Longfellow.

The name Alle Grazie came from an image of the Virgin in a little chapel situated on the right bank. The quaint houses which stood on the piers were originally hermitages erected by nuns who, shocked at the immorality of their convents, lived here in retreat—Romite del Rubaconte—under the direction of one Madonna Apollonio. In one of these little houses was born the Beato Tommaso de’ Bellacci, and in another the poet Benedetto Menzini, in 1646. The little church of S. Maria delle Grazie, founded by the Alberti, has been removed to the Lung’ Arno Generale Diaz8Armando Diaz was a WWI Italian general. The Lung’Arno was renamed in November, 1818. (formerly Lung’ Arno della Borsa), and still contains an ancient Madonna, regarded in Florence as miraculous. On the Lung’ Arno delle Grazie, to the west of the bridge, an inscription on No. 20 records that it was the home of Niccolò Tommaseo (1802–68), an author of some celebrity in his time.

Cesare Bazzani. Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, 1911-35 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale faces the little Piazza dei Cavalleggieri, named from the barracks of the Spanish Guard of the Grand Duke after 1543. Formerly located in the Uffizi, the library originated in 1714 with a bequest of approximately 30,000 volumes from Antonio Magliabechi a book collector who had served as Palatina and Laurenziana libraian. Cesare Bazzani designed the current building in a Neo-Renaissance style in 1911. The projecting center pavilion consists of a 3-bay loggia flanked by square towers. The contents of the library were severely damaged in the November 1966 Arno flood.

On Via de’ Benci, the street leading from the bridge to the Piazza S. Croce, is the Horne Museum (No. 6) located in the former Palazzo Corsi, built c. 1500 from designs by Il Cronaca or, less likely, by Giuliano da Sangallo. Herbert Percy Horne (1864 –1916), an English art historian, poet, typographer, and antiquarian, purchased the Palazzo Corsi in 1911 to house his collection of early Renaissance art, which he bequeathed to the state. The collection is displayed without labels in rooms reconstructed to emulate those of a 15th-century Florentine palace. Artists represented include Giotto, Masaccio, Luca della Robbia, and numerous works by artists whose identity is unknown.

Via de’ Benci was once almost lined by the palaces and towers of the Alberti family.9Arms of Alberti: Az., 4 chains in saltire, argent, meeting in a ring. At the Canto delle Colonnini, at the corner of the Borgo S. Croce, is a loggia which belonged to them, and which was once the workshop of Niccolò Grossi, surnamed Caparra (earnest-money) by Lorenzo de’ Medici, because he refused to undertake any work unless he was partially paid in advance. Opposite this stood the Church of S. Jacopo tra Fossi, recalling in its name the moat under the second circle of the city walls, and occupying part of the site of the Roman Amphitheatre, in which San Miniato was twice exposed to wild beasts in the reign of Decius (A.D. 249). In the neighbouring Borgo S. Croce lived Giorgio Vasari. On one side of the Palazzo Cocchi, at the corner of the Piazza S. Croce, is a huge hinge—a remnant of the Porta delle Pere, spoken of by Dante—

Nel picciol cerchio s’ entrava per porta

Che si nomava da quei della Pera.

One entered the small circuit by a gate

Which from the Della Pera took its name!

Dante Paradiso 16:125–26. Trans. Longfellow.