9.1: Vallombrosa, Casentino, La Vernia & Camaldoli

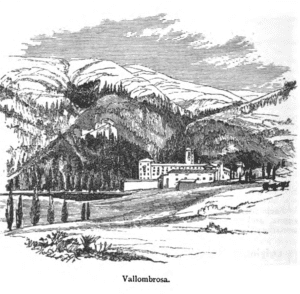

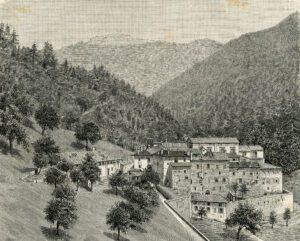

Vallombrosa may easily be visited in a long summer day. The road to the monastery ascends through pine woods, which recall Norway or Switzerland, to the beautiful meadows, fresh with running streams and most brilliant with spring flowers, at the end of which, at a height of 3140 feet, stands Vallombrosa. It would seem as if the recollection of this ascent had suggested the lines of Milton:

So on he fares, and to the border comes

Of Eden, where delicious Paradise,

Now nearer, crowns with her enclosure green,

As with a rural mound, the champaign head

Of a steep wilderness, whose hairy sides

With thickets overgrown, grotesque and wild,

Access denied; and overhead up grew

Insuperable height of loftiest shade,

Cedar, and pine, and fir, and branching palm,

A sylvan scene, and as the ranks ascend

Shade above shade, a woody theatre

Of stateliest view.

John Milton, Paradise Lost, 4:131ff.

Here sublime

The mountains live in holy families.

And the slow pine woods ever climb and climb

Half up their breasts, just stagger as they seize

Some grey crag, drop back with it many a time,

And struggle blindly down the precipice.

O waterfalls

And forests! sound and silence! mountains bare

That leap up peak by peak and catch the palls

Of purple and silver mist to rend and share

With one another, at electric calls

Of life in the sunbeams,—till we cannot dare

Fix your shapes, count your number! we must think

Your beauty and your glory helped to fill

The cup of Milton’s soul to the brink.

He never more was thirsty when God’s will

Had shattered to his sense the last chain-link

By which he had drawn from Nature’s visible

The fresh well-water. Satisfied by this,

He sang of Adam’s Paradise and smiled.

Remembering Vallombrosa. Therefore is

The place divine to English man and child,

And pilgrims leave their soul here in a kiss.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Casa Guidi Windows, 1.

Such scenery, such hilly peaks, such black ravines and gurgling waters, and rocks and forests above and below, and at last such a monastery!

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Letters, vol. 1, pp. 342–43.

Originally Vallombrosa bore the name of Acqua Bella. The convent owes its origin to the penitence of S. Giovanni Gualberto (A.D. 1015) (see S. Miniato), who first lived here in a little hut. Other hermits collected around him, and as the numbers increased, he found it necessary to form the community into an order and gave them the rule of S. Benedict, adding some additional obligations, especially that of silence. Yet the rule was less severe than that of the Camaldolese. Only twenty years had passed from the time of his death when Giovanni Gualberto was canonised, and within the first century of its existence his order possessed fifty abbeys. The abbots of Vallombrosa sate in the Florentine senate with the title of Counts of Monte Verde and Gualdo, and they could arrest, try, and imprison their vassals without reference to any other court. The habit of the Vallombrosans was of light grey.

Originally Vallombrosa bore the name of Acqua Bella. The convent owes its origin to the penitence of S. Giovanni Gualberto (A.D. 1015) (see S. Miniato), who first lived here in a little hut. Other hermits collected around him, and as the numbers increased, he found it necessary to form the community into an order and gave them the rule of S. Benedict, adding some additional obligations, especially that of silence. Yet the rule was less severe than that of the Camaldolese. Only twenty years had passed from the time of his death when Giovanni Gualberto was canonised, and within the first century of its existence his order possessed fifty abbeys. The abbots of Vallombrosa sate in the Florentine senate with the title of Counts of Monte Verde and Gualdo, and they could arrest, try, and imprison their vassals without reference to any other court. The habit of the Vallombrosans was of light grey.

The greatest severity was used toward them during the suppression of the religious orders, and scurrilous libels upon the past history of Vallombrosa were purposely circulated. Yet the records of the Archivio show that in old times as many as 229,761 loaves of bread were distributed here to the poor in three years (1750–53), not inclusive of the hospitalities of the Foresteria, and in the same space of time as many as 40,300 beech-trees were planted on the neighbouring mountains by the monks.

The buildings of Vallombrosa are inferior in interest to those of other sanctuaries, and it owes its celebrity chiefly to its beautiful name and to the felicitous allusion in Milton. The church is handsome. The vast convent was chiefly built, as it now stands, by the Abbot Averardo Nicolini in 1637. While the monks remained, strangers were always hospitably received here.

Vallombrosa;

Così fu nominata una badia

Ricca e bella, nè men religiosa

E cortese a chiunque vi venia

To Vallombrosa’s fane, an abbey gray

Rich, fair, nor less religious, and beside,

Courteous to whosoever passed that way.

Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando Furioso, vol. 1, p. 435.

Since the suppression the place has lost many of its characteristic features, the monastic buildings were used as a school for the training of foresters, and the Foresteria was a pension annexed to the hotel Croce di Savoia.

All around the former convent are woods, the woods which came back to Milton’s memory when he wrote—

Thick as autumnal leaves that strew the brooks

In Vallombrosa, where the Etrurian shades,

High-overarch’d, imbower

John Milton, Paradise Lost, 1:303–05.

In the present century the woods have been celebrated in a poem by Alphonse de Lamartine. But nowhere has the mad destruction of old trees in Italy been carried to such an excess as at Vallombrosa. An Englishman offered to pay the fullest timber price for some of the finest trees which adorned the ascent from Pelago if they might be left standing in their places; his offer was refused, and every tree of any age or beauty was destroyed, and sold to a walking-stick manufacturer. The noble wood on the ridge of the hill, which sheltered all the young plantations, has been annihilated in the same way. “Away with it, cut it down, root it up,” is always the cry of an Italian official against a fine tree and remonstrance is in vain.

It is worth while to ascend to the Hermitage and Chapel of Il Paradisino, some way farther up the mountain, for the sake of the view. The scagliola decorations in the chapel were executed by Henry Hugford, an Englishman, who sought a retreat here.

The ascent of the Secchietta (4744 feet) from Vallombrosa occupies two hours. There is a rewarding view from the chapel called Il Tabernacolo di Don Piero.

A long ascent from Pontassieve, of ten dreary miles, leads to the entrance of the Casentino. Near the summit is the miserable village of Consuma, which derives its strange name from the death of one Adam, who was burnt alive here for having forged false florins of the Republic at the instigation of the Counts of Romena. A short distance beyond and we look down upon the rich valley of the Upper Arno, called Il Casentino. Hence we first caught sight, in the distance to the left, of the arid brown steep of Alvernia, “the Holy Mountain” of S. Francis. The road passes through the village of Borgo alla Collina, with a castle which was bestowed by the Florentine Republic upon Cristofano Landino, as a reward for his commentary on Dante; he is preserved like a mummy in the parish church. Descending into the valley, we cross the plain of Campaldino, where the Ghibelline troops of Arezzo were completely routed by the Florentine Guelfs, and where their famous warrior-bishop, Guglielmo Ubertini, was killed, June 11, 1289. Dante was present, serving in the mounted infantry (c.f. Purg., Canto v.).

It was in the plain of Campaldino, now laughing and covered with vines, that a fierce battle took place between the Guelphs of Florence and the Ghibelline Fuorisciti, assisted by the Aretines. Dante had to fight in the first rank of the Florentine cavalry, for this man, whose life had been so complete, had to have been a soldier before becoming theologian, diplomat, poet. He was then twenty-four years old. He himself recounted this battle in a letter of which only a few lines remain. “At the battle of Campaldino the Ghibelline party was almost entirely dead and defeated. I found myself there a novice in arms; I had great fear there, and, in the end, great joy, on account of the various chances of the battle.” This sentence should not be seen as an admission of a lack of courage, which could not be found in a soaked soul like that of Alighieri. The only fear he had was that the battle would be lost. In fact, the Florentines at first appeared beaten; the Aretine cavalry made their infantry fold; but this first advantage of the enemy lost him by dividing his forces.

To this short campaign we owe perhaps one of the most admirable and famous pieces of the Divine Comedy. It was then that Dante made friends with Bernardino della Polenta, brother of this Françoise of Ravenna whom the place of her death had wrongly called Françoise de Rimini. We can believe that the friendship of the Poet for the brother made him even more sensitive to the misfortunes of the sister.

Jean-Jacques Ampère, La Grèce, Rome & Dante, pp. 241–42.

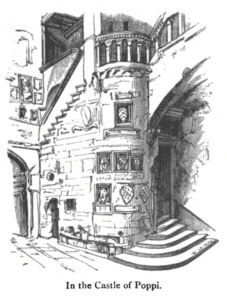

Crowning a hill about a mile to the right of the road is the town of Poppi, the old capital of the Casentino, with a station on the line from Arezzo to Stia. Its Castle, something like the Palazzo Vecchio at Florence on a small scale, was built by Arnolfo del Cambio, in 1274, for Count Simone, grandson of Count Guido Guerra. It stands grandly at the end of the town, girdled by low towers. In its courtyard is a most picturesque staircase, quite different (as will be seen by the annexed woodcut) from that of the Bargello at Florence, which is wrongly said to have been copied from it. In the chapel are frescoes attributed to Spinello Aretino. A chamber is shown as that of “la buona Gualdrada,” mentioned by Dante (Inf. 16:37), the beautiful daughter of Bellincione Berti, who declared to Otho IV., when he demanded her name, that she was the daughter of a man who would compel her to embrace him; upon which the maiden herself arose and said, “No man living shall ever embrace me, unless he is my husband.” Dante stayed here as the guest of the Contessa Battifolli.

Raphael, Cardinal Bibbiana, c. 1516 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

About 4 miles beyond Poppi is the pleasant little town of Bibbiena, which also has a station between Arezzo and Stia, and which contains a fine work of one of the della Robbia in the Church of S. Lorenzo. Here Bernardo Dovizi, 1470–1520, was born, the secretary and friend of Giovanni de’ Medici, who, when raised to the pontificate as Leo X., made him Cardinal Bibbiena. Raffaelle painted the fine portrait of this Cardinal now in the Pitti Palace, and might, had he been willing, have married his niece. Forsyth recalls how Bibbiena has been

Long renowned for its chestnuts, which the peasants dry in a kiln, grind into a sweet flour, and then turn into bread, cakes, and polenta. Old Burchiello sports on the chestnuts of Bibbiena in these curious verses, which are more intelligible than the barber’s usual strains: —

Ogni castagna in camicia e ‘n pelliccia

Scoppia, e salta pel caldo, e fa trictacohe,

Nasce in mezzo del mondo in cioppa riccia;

Secca lessa, e arsiccio

Si da per frutte a desinar e a cena;

Questi sono i confetti da Bibbiena.

Every chestnut in a shirt is in fur

It bursts, and jumps in the heat, and makes grinds,

Born in the middle of the world in curly lock;

Dry boiled, and arsiccio

It is given as fruit to dine and supper;

These are the confetti from Bibbiena.

Joseph Forsyth, Remarks, p. 127.

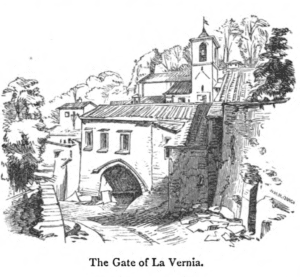

The convent of to La Vernia or Alvernia occupies the summit of a mountain which was bestowed upon S. Francis, in 1224, by the knight Orlando da Chiusi, who was moved thereto by the preaching of the Saint in the castle of Montefeltro. “I have a mountain,” said Orlando, “in Tuscany, a devout and solitary place, called Mount Alvernia, far from the haunts of men, well fitted for him who would do penance for his sins, or desires to lead a solitary life; this, if it please thee, I will freely give to thee and thy companions for the welfare of my soul.” S. Francis gladly accepted, but the monks who first took possession of the rocky plateau, and built cells there with the branches of trees, were obliged to have a guard of fifty armed men to protect them from the wild beasts.

Our path crosses the torrent Corselone, and then begins at once to ascend. The whole of the way is alive with the recollections of S. Francis, as given in the Fioretti. It was in the woods which we pass through that he vanquished demons in conflict during his first ascent, while his companions, overwhelmed with fatigue, had fallen asleep in the shade. Then, —

Beating his breast, he sought after Jesus, the beloved of his soul, and having found Him at last, in the secret of his heart, now he spoke reverently to Him as his Lord, now he made answer to Him as his judge, now he besought Him as his father, now he conversed with Him as his friend. On that night and in that wood, his companions, awaking and listening to him, heard him with many tears and cries implore the Divine mercy on behalf of sinners.

Leaving the wood, we enter upon the steeper and hotter part of the ascent, where —

The next morning his companions, knowing that he was too weak to walk, went to a poor labourer of the country, and prayed him, for the love of God, to lend his ass to Brother Francis their father, for he was not able to travel on foot. Then that good man made ready the ass, and with great reverence caused S. Francis to mount thereon. And when they had gone forward a little, the peasant said to S. Francis, “Tell me, art thou Brother Francis of Assisi?” And S. Francis answered “Yes.” “Take heed then,” said the peasant, “that thou be in truth as good as all men account thee; for many have great faith in thee, and therefore I admonish thee to be no other than what the people take thee for.” And when S. Francis heard these words, he was not angry at being thus admonished by a peasant, but instantly dismounting from the ass, he knelt down upon the ground before that poor man, and, kissing his feet, humbly thanked him for that his charitable admonition.

We skirt the stream, which the legend says issued forth from the hard rock by virtue of the prayers of S. Francis, and lastly, as we reach the flowering meadows below the convent, we see, upon the right, a group of old trees, shading some rocks and unprofaned by the axe, for —

As they drew near to Alvernia, it pleased S. Francis to rest a while under an oak, which may still be seen there, and from thence he began to consider the position of the place and the country. And while he was thus considering, behold there came a great multitude of birds of divers regions, which, by singing and clapping their wings, testified great joy and gladness, and surrounded S. Francis in such wise that some perched on his shoulders, some on his arms, some on his bosom, and others at his feet, which when his companions and the peasant saw, they marvelled greatly; but S. Francis, being joyful of heart, said to them, “I believe, dearest brethren, that our Lord Jesus Christ is pleased that we should dwell on this solitary mount, inasmuch as our brothers and sisters, the birds, show such joy at our coming.”1George Sand declared herself to have the same extraordinary attractive power over all animals which characterised S. Francis.

From hence we see the conventual buildings most picturesquely grouped on the perpendicular rocks, which rise abruptly from the grass, and backed by woods of pine and beech. Here it was that brother Leo often imagined that —

He beheld S. Francis rapt in God and suspended above the earth, sometimes at the height of three feet above the ground, sometimes four, sometimes raised as high as the beech-trees, and sometimes so exalted in the air, and surrounded by so dazzling a glory, that he could scarce endure to look upon him.

A rock-hewn path takes us to the arched gateway of the sanctuary, which has been enlarged at many different periods since its foundation by S. Francis in 1213, but which to Roman Catholics will ever be one of the most sacred spots in the Christian world, from its connection with the Saint, who always passed two months here in retreat, and who here is believed to have received the Stigmata, by which he became especially likened to the Master whose example he was always following, and thus, a radiative centre of love.

It was here that S. Francis learned the tongues of the beasts and birds, and preached them sermons. Stretched for hours motionless on the bare rocks, coloured like them, and rough like them in his brown peasant’s serge, he prayed and meditated, saw the vision of Christ crucified, and planned his Order to regenerate a vicious age. So still he lay, so long, so like a stone, so gentle were his eyes, so kind and low his voice, that the mice nibbled bread crumbs from his wallet, lizards ran over him, and larks sang to him in the air. Here, too, in those long solitary vigils, the Spirit of God came upon him, and the spirit of Nature was even as God’s Spirit, and he sang “Laudato sia Dio mio Signore, con tutte le creature, specialmente messer lo frate sole; per suor luna, e per le stelle; per frate vento, e per 1’aria e nuvolo, e sereno, e ogni tempo.” [“Be praised my Lord, through all Your creatures, especially Sir Brother Sun; through Sister Moon and the stars; through Brothers Wind and Air, cloudy and serene, and all weather.”] Half the value of this hymn would be lost were we to forget how it was written, in what solitudes and mountains far from men, or to ticket it with some cold word like Pantheism. Pantheism it is not, but an acknowledgment of that brotherhood, beneath the love of God, by which the sun and moon and stars, and wind and air and cloud, and clearness and all weather, and all creatures, are bound together with the soul of man.

Here is a sentence of Imitatio which throws some light upon the hymn of S. Francis, by explaining the value of natural beauty for monks who spent their lives in studying death. “If thy heart were right, then would every creature be to thee a mirror of life and a book of holy doctrine. There is no creature so small and vile that does not show forth the goodness of God.” With this sentence bound about their foreheads, walked Fra Angelico and S. Francis. To men like them the mountains, valleys, and the skies, and all that they contained, were full of deep significance. Though they reasoned “de conditione humanae miseriae” [the condition of human misery] and “de contemptu mundi” [contempt of the world] yet the whole world was a pageant of God’s glory, a poem to His goodness. Their chastened senses, pure hearts, and simple wills were as wings by which they soared above the things of earth, and sent the music of their souls aloft with every other creature in the symphony of praise. To them, as to Blake, the sun was no mere blazing disc or ball, but an innumerable company of the heavenly host, singing, “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God Almighty.” To them the winds were brothers, and the streams sisters brethren in common dependence upon God their Father, brethren in common consecration to His service, brethren by blood, brethren by vows of holiness. Perfect faith rendered this world no puzzle; they overlooked the things of sense because the spiritual things were ever present and as clear as day. Yet they did not forget that spiritual things are symbolised by things of sense; and so the smallest herb of grass was vital to their tranquil contemplations. We, who have lost sight of the invisible world, who set our affections more on things of earth, fancy that because these monks despised the world, and did not write about its landscapes, therefore they were dead to its beauty. This is mere vanity; the mountains, stars, seas, fields, and living things were only swallowed up in one thought of God, and made subordinate to the awfulness of human destinies. We to whom hills are hills, and seas are seas, and stars are ponderable quantities, speak, write, and reason of them as of objects interesting in themselves. The monks were less concerned about such things because they only found in them the vestibules and symbols of a hidden mystery.

“On the Cornice,” Cornhill Magazine, vol. xiv (November 1866), pp. 545–547.

La Vernia is one of the few great religious shrines which have not been confiscated by the Government. It originally belonged to the Arte della Lana, who conceded it to the Grand-Dukes; they in their turn made it over to the Municipality of Florence, who have defended their property. Annually the representatives of the Municipality come in mediaeval fashion, plant their standard on the convent platform, and inspect the buildings and woods. A hundred and seven brown monks still reside in the vast buildings. They change their names when they “enter into religion,” and take that of some saint to whom they especially devote themselves. On payment of the sum of 100 francs any peasant may become a Franciscan monk, with the prospect of eventually entering the priesthood. At La Vernia about 125 francs are required at the end of the novitiate for titolo di vestiario, or the expense of the habit. Strangers are hospitably received by the monks, and share with them the fare which they have, though it is of a wretched description. They have no property whatever except the garden where their salad is raised, and the neighbouring bosco. In the summer, when the air is always fresh on these mountain heights, and the woods resound with nightingales, their residence is pleasant enough, but it is terribly severe during the nine months of winter, and the cold is intolerable in their fireless cells. Eight hours of the twenty-four are passed in the church, one hour and a half being soon after midnight. Twice in the week the monks kneel in the midnight around the marble slab where the stigmata were inflicted, and as the five lamps in memory of the five wounds of S. Francis are extinguished, they scourge themselves in the total darkness, and the clanging of the iron chains of their self-inflicted punishment mingles with the melancholy howls of the winds around the stone corridor. Twice in the twenty-four hours they join in a chanting procession down the long covered gallery on the mountain edge in honour of the stigmata. During the remaining hours those monks who have to preach study for their sermons (the famous preacher Ferrara is a Franciscan), the doctors of the poor employ themselves in the speziería, others perform the manual labour of the vast establishment. They take little notice of the events of the outer world, and, as far as is apparent, seem contented with their monotonous lot. We asked some of them if they never felt tired of it—“Ah no; life is so short, but eternity so long.” Seeing the exquisite beauty of the bosco in spring, with its carpet of violets, primroses, daffodils, cyclamen, squills, saxifrage, and a thousand other flowers, we asked a monk if their loveliness was not a pleasure to him—“Ma perche? non mi sono mica confuso con la botanica” [But why? I am not distracted with botany] was the answer.

Subsisting entirely on the alms of the surrounding farmers and contadini, the monks, after a fashion, pay back what they have received on the great festas when the pilgrimages to La Vernia take place. Then all the pilgrims, often to the number of 300, are received, and, if they require it, are fed; not in guest-rooms, of which there are only twenty-four, these being generally reserved for “personaggi,” but encampments are made for them in the bosco or on the flagged terraces, upon which the brown figures of the monks—as they pace up and down and are seen relieved against the pale violet mountains—look as if the statues of S. Francis and S. Antonio had stepped from their niches and come back into life.

I felt with Dante in this place full of the memory of the miracles of Saint Francis, on this harsh rock of the Apennines, from which the famous order spread over the world which regenerated the Catholicism of the Middle Ages, and whose founder was so magnificently exalted by the poet of Catholicism and of the Middle Ages. The faith of the thirteenth century was still there. Brother Jean-Baptiste took me to the various places that witnessed the marvels performed by Saint Francis. As he told me about these marvels, he seemed to see them. “It is here,” he said, “that the miracle takes place; the saint was where I am.” And in pronouncing these words, the physiognomy, the voice, the gestures of Brother Jean-Baptiste expressed an invincible certainty. He showed me rocks split and broken by some geological accident, and said to me: “See how the bosom of the earth was torn in the night when Christ descended into hell to seek there the souls of the righteous dead. before his coming! How else to explain this disorder? I am not telling you this: you see it with your own eyes, you see it!”

I listened with all the more interest, as Dante alludes to the same belief. To pass into the circle of the violent, he must cross a landslide of rocks to which Virgil, his guide, attributes a similar origin. He relates it in the same way to the trembling which agitated the abyss on the day when Christ descended. Virgil told Dante exactly what Brother John the Baptist was telling me.

Andrea della Robbia, Madonna della Cintola (girdle), c. 1486 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The principal Church contains several fine works of the della Robbia family, that of the Ascension being magnificent. The church opens upon the terraced platform where Orlando finally made over the mountain to the Saint, and where, on their first arrival —

Francis caused his companions to sit down and taught them the manner of life they were to keep, that they might live religiously in this solitude; and, among other things, most earnestly did he enjoin on them the strict observance of holy poverty, saying, “Let not Orlando’s charitable offer cause you in any way to offend against our lady and mistress, holy Poverty. God has called us into this holy religion for the salvation of the world, and has made this compact between the world and us, that we should give it good example, and that it should provide for our necessities. Let us then persevere in holy poverty; for it is the way of perfection and the pledge of eternal riches.”

Close by is the site of the great beech-tree which over-shadowed the first cell—tuguriolo—of S. Francis, atto e divoto alla orazione [act and devoted to prayer]—in which he lived while the convent was being built, and where he sought the guidance of God by making the sign of the cross over his Bible, and then opening it at a venture. Each time the book opened at the story of the Passion of our Saviour, and hence he deduced that the remaining years of his life (for he was already in failing health) were to be as one long martyrdom, and that, in the words of his biographer Celano, “through much anguish and many struggles he should enter the kingdom of God.” The stone altar is shown whither Christ descended to hold visible converse with His servant. Beneath this is a valley of rocks, rising in huge and fantastic pinnacles against one another, and according to the legend, riven into these strange forms at the time of the Crucifixion. Over these rocks, fifty-three metres high, it is said that the Devil hurled S. Francis, and the hole is shown at the point which he lodged, when “the stone became as liquid wax to receive him.” In the inmost recesses of the deepest cleft is the secret caverned space, where, perpetually chanting the Penitential Psalms, S. Francis passed the “Lent of S. Michael.” One monk alone, Brother Leo, was permitted to approach him, once in the day, with a little bread and water, and once at night, and, when he reached the narrow causeway at the entrance, was bidden to say, “Domine labia mea aperies” [God will open my lips]; when, if an answer came, he might enter the cell and repeat matins with his master; but if there was silence, he must forthwith depart. In a second cave, covered with iron to prevent its being carried away piecemeal by the faithful, is a great flat stone—“il letto di San Francesco” [the bed of St. Francis]. Outside is the point of rock where —

Through all that Lent, a falcon, whose nest was hard by his cell, awakened S. Francis every night a little before the hour of matins by her cry and the flapping of her wings, and would not leave him until he had risen to say matins; and if at any time S. Francis was more sick than ordinary, or weak, or weary, that falcon, like a discreet and charitable Christian, would call him somewhat later than was her wont. And S. Francis took great delight in this clock of his, because the great carefulness of the falcon drove away all slothfulness, and summoned him to prayers; and, moreover, during the daytime she would often abide familiarly with him.

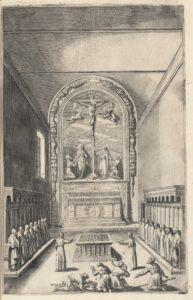

In another chapel is shown the grave of all the monks of La Vernia who have died in “the odour of sanctity,” that is, who have been distinguished by blue lights—corpse candles—hovering over their dead bodies. In another is the cell of S. Bonaventura, in another that of S. Antony of Padua, who came here into retreat, but was driven away by ill-health. The Chapel of the Stigmata contains one of the largest and grandest works of Andrea della Robbia—a Crucifixion, with the Virgin and S. John, S. Jerome and S. Francis, standing at the foot of the cross, surrounded by the most beautiful weeping and adoring angels.

Andrea della Robbia, Crucifixion, 1480-81 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The great church contains one of Andrea della Robbia’s sweetest Nativities, together with an annunciation very like the lunette of the Spedale degli Innocenti; in the Chiesina we have a large relief of the Madonna giving the measure of the chapel to S. Bonaventura, dated 1486; while the chapel of the Stigmata—the Holy of Holies—has a grand Crucifixion, the finest rendering of the subject in Della Robbia art. The heads of the Saints, S. John, S. Benedict, and others, at the foot of the cross, are unequalled in beauty of expression; that of Francis himself, in its intensity of yearning, reminds us of S. Giovanni Gualberto in Perugino’s Vallombrosa altar-piece, and every shade of grief and wonder is displayed in the gestures and faces of the angels hiding their eyes and clasping their hands wildly together, as they hover round the dying Lord. Nowhere does Andrea better reveal the depths of feeling that lived in his gentle breast; never before had terra-cotta been used to express passion so profound, or emotions of so varied and subtle a nature.

British Quarterly Review, Oct. 1885.

This chapel occupies that point in the desert where the story tells that—

S. Francis being inflamed by the devout contemplation of the Passion of Jesus Christ, beheld a seraph descending from heaven with six fiery and resplendent wings, bearing the image of One crucified.

And while S. Francis marvelled much at such a stupendous vision, it was revealed to him that by Divine providence this vision had been shown to him that he might understand that not by the martyrdom of his body, but by the consuming fire of his soul, he was to be transformed into the express image of Christ. “Then did all the Mont’ Alvernia appear wrapped in intense fire, which lit up all the mountains and valleys around, as it were the sun shining in strength upon the earth, whence the shepherds who were watching their flocks in that country were filled with fear, as they themselves afterwards told the brethren, affirming that this light had been visible on Mont’ Alvernia for upwards of an hour; and because of the brightness of that light, which shone through the windows of the inn where they were resting, muleteers who were travelling in the Romagna rose in haste supposing that the sun had arisen, and saddled and loaded their beasts; but as they journeyed on, they saw that light die down and the visible sun come forth.”

In this seraphic apparition, Christ spoke certain high and secret things to S. Francis, saying, “Knowest thou what I have done to thee? I have given thee the Stigmata which are the ensigns of my Passion, that thou mayest be my Standard-bearer.” And when the marvellous vision disappeared, upon the hands and feet of S. Francis the print of the nails began immediately to appear, as he had seen them in the body of Christ crucified. In like manner, on the right side appeared the image of an unhealed wound, as if made by a lance, still red and bleeding, from which drops of blood often flowed and stained the tunic of S. Francis. Although these sacred wounds impressed upon him by Christ afterwards gave great joy to his heart, yet they caused unspeakable pain to his body; so that, being constrained by necessity, he made choice of Brother Leo, for his great purity and simplicity, and suffered him to touch and dress his wounds on all days except during the time from Thursday evening to Saturday morning, for then he would not by any human remedy mitigate the pain of Christ’s Passion, which he bore in his body, because at that time our Saviour Jesus Christ was taken and crucified and died for us.2Celano, the earliest biographer of S. Francis, wrote three years after his death, and must have been in possession of everything then known and believed on the subject of the Stigmata. The ‘ Three Companions ‘ did not compose their narrative until twenty years after his death; but they were his constant companions during his life, and two out of the three are reported to have been with him on Mount Alverno. Bonaventura is the latest of all. His work was written in 1263, thirty-seven years after the death of the Saint; but he had lived all his life among those who had known and loved Francis, and had the fullest information at his command.

Contemporary witnesses of perfect trustworthiness and high character believed in the fact of the Stigmata, and vouch for it. It is not an afterthought, a pious invention for the use of a canonising Pope, but the evident belief of the time, arising out of something in the life of Francis which attracted the wonder and curiosity and eager guesses of his companions. With a few exceptions the wonder was received with perfect faith by his generation. It was affirmed and proclaimed authoritatively by two Popes, who were his personal friends, and must have had means of knowing whether the tale were false or true. One of them, indeed, Pope Alexander VI., Bonaventura tells us, publicly asserted that he had himself seen the mysterious wounds. The evidence altogether is of a kind which it is almost equally difficult to accept or to reject. There is sufficient weight of testimony, when fully considered, to stagger the stoutest unbeliever; and there is too much vagueness and generality to make the most believing mind quite comfortable in its faith. Mrs. Oliphant, Francis of Assisi, pp. 255, 259, & 267.

Another chapel contains an Assumption by one of the Della Robbia. The Madonna is portrayed as giving the measure of this very chapel to S. Bonaventura, by whom it was built. The measure thus consecrated has never been altered, though an ante-chapel has been added, containing a Robbia Nativity and a Pietà.

The poor friars of La Vernia are more loved and respected by the people who feed them than any of the chartered orders. Obliged and obliging, they mix intimately with the peasants, as counsellors and comforters and friends. In hospitals, in prisons, and on the scaffold, in short, wherever there is misery you find Franciscans allaying it. Having nothing, yet possessing all things, they live in the apostolical state.

Joseph Forsyth (1811). Remarks, pp. 124–25.

Most beautiful are the forest walks behind the convent, fragrant with the memories of holy Franciscan monks. “In these woods,” says Sir J. Stephen, “S. Francis wandered in the society of Poverty, his wedded wife; relying for support on Him alone by whom the ravens are fed, and awakening the echoes of the mountains by his devout songs and fervent ejaculations.” Here, in the emerald avenues, Brother James of Massa beheld in a vision all the Friars Minor in the form of a tree, from whose branches the evil monks were shaken by storms into perdition, while the good monks were carried by the angels into life eternal. Here the venerable Brother John of Fermo wandered, weeping and sighing in the restless search after divine love, till, when his patience was sufficiently tried, Christ appeared to him in the forest-path, and, with many precious words, restored to him the gift of grace. And “for a long time after, whenever Brother John followed the path in the forest where the blessed feet of Christ had passed, he saw the same wonderful light and breathed that same sweet odour,” which had come to him with the vision of his Saviour. From the highest part of the rock called La Penna (4165 ft.) is the most glorious view. In the shadowed depths of the gorges beneath, on one side rises the Arno, and on the other, in the mountain of La Falterona (5410 ft.), the Tiber.

A little south of the monastery is the ruined Castle of Chiusi, on the site of Clusium Novum, where the father of Michelangelo, Ludovico Buonarroti, held the office of Podesta. In this district also in the valley of the Singorna, is the village of Caprese, where the great master was born, March 6, 1475, though his parents removed to Settignano in the following year.

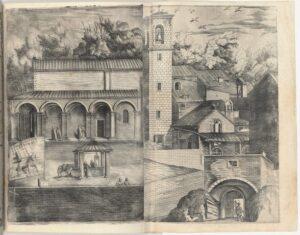

Most travellers will follow the road from Bibbiena to Camaldoli. The direct path is a wild and most exhausting ride of five hours. Descending between the beautiful moss-grown trees and steep rocks of Alvernia, the way (impossible without a guide) winds through woods to Soci, a flourishing village with manufactories of cloth. After this it is a stony road, ascending into arid and hideous earth-mountains. Crossing the highest ridge, it descends rapidly into a deep valley backed by pine-woods, and fresh with streams and flowers, an oasis in a most dreary wilderness. Here, in the depth of the gorge, close to the torrent Giogana, is the immense mass of the Convent of Camaldoli (2717 ft.), originally called Fonte Buona, which was founded by S. Romualdo, about A.D. 1012, and became the cradle of his order.

Giuseppe Barberis, Convento di Camaldoli, 1884 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The ancient buildings were strongly fortified, and successfully withstood a damaging siege by the Duke of Urbino and the Venetians in 1498, when forty of the assailants were killed and the Duke himself wounded. It was again successfully defended against the forces of Piero de’ Medici, when he was attempting to regain his lost power in Florence, by the Abbot Basilio Nardi, who is introduced by Vasari in one of his battle-pieces in the Palazzo Vecchio. On this occasion, according to monkish legend, S. Romualdo visibly fought in defence of his foundation. The present edifice has little interest, having been rebuilt under Vasari in 1523. From the Sala dell’ Accademia, “where Cristoforo Landino, Lorenzo de’ Medici, and Marsilio Ficino held examinations,” there is a beautiful view down the forest-clad gorge. The fine library has been dispersed, and the only literary treasure remaining is a commentary on the earlier part of the Psalms, written by S. Romualdo in the eleventh century. The church contains some pictures by Vasari. The grave of the Bishop of Antwerp, who died here a refugee from persecution, has the touching inscription: “Hic jacet Cornelius Fran. de Nelli, Episc. Anverp., peccator et peregrinus.” [Here lies Cornelius Fran. de Nelli, Bishop of Antwerp, sinner and foreigner] In the Cappella del Infermeria is a Christ in the Desert—a good work of Raffaellino del Garbo. The famous painter on glass, Guglielmo da Marcilla (1475–1537), bequeathed his property with his body to the monks of Camaldoli. The dependent buildings of the convent included a well-managed farm, a forge, a carpenter’s shop, a mill, and the sega or sawmill, which is worked by the torrent. The charities of the monks of Camaldoli were proverbial; 1000 families of the Casentino depended on the convent for work or help. In addition to other alms, 600 loaves of bread were weekly prepared in the bakehouse for the destitute poor.

The monks of Camaldoli follow the rules approved in 1671 by Clement X. Their principal observances consist in psalm-singing, meditation, and the labour of their hands. They never meet at a common table except on the great feasts of the Church, and when the General Chapter is sitting. They never eat meat, and that which they call fasting is abstinence from eggs and anything cooked with butter, and on days which are not fast-days their portion is confined to three eggs, or six ounces of fresh or four of salt fish. Their dress is a white serge tunic and scapulary, with a woollen girdle. The mantle of the same (used in choir and procession) has an ample hood. The famous Cardinal Placido Zurla and Mauro Cappellari—afterwards Pope Gregory XVI.—were Camaldolese monks. The painters Lorenzo Monaco and Giovanni degli Angeli also belonged to this Order.

Andrea Sacchi, Vision of Saint Romuald , 1631

About an hour’s walk through the forest higher up the valley, on a grassy plateau, is a second convent, or rather little street of twenty-four hermitages, called Il Sacro Eremo, which is interesting from its connection with the story of S. Romualdo, a member of the noble family of the Onesti of Ravenna, who was led to embrace the monastic life from the horror he experienced when present at a duel in which his father slew a near relation of his house. He first entered the monastery of S. Apollinare in Classe, where his austerities soon made him odious to the more lukewarm monks, and caused him to retire into the deserts of Catalonia, where he was joined by many disciples. In 1009 he received from the Counts of Maldoli a gift of the lands upon which this, his greatest monastery, was founded, and which has ever borne the name of Campo-Maldoli, Camaldoli. By the observances which he here added to the rule of S. Benedict, he gave birth to the new order of Camaldoli, which united a cenobite and an eremite life. At the Sacro Eremo he saw in a vision his monks mounting in white robes by a ladder to heaven, and so changed the habit from black to white. This vision is the subject of the famous altar-piece of Andrea Sacchi, painted for the church of the Camaldolesi at Rome, and now in the Vatican gallery. The first inhabitants of the hermitages were the five chosen companions of S. Romualdo—Dagnino, Benedetto, Gisso, Teuzzone, and Pietro.

The whole hermitage is enclosed within a wall; none are allowed to go out of it; but the hermits may walk in the woods and alleys within the inclosure at discretion.

Everything is sent them from the monastery in the valley; the food is every day brought to each cell; and all are supplied with wood and necessaries, that they may have no dissipation or hindrance in their contemplation. Many hours of the day are allotted to particular exercises, and no rain or snow prevents any one from meeting in the church to assist at the divine office. They are obliged to strict silence in all public common places; and everywhere during their Lents, also on Sundays, Holy days, Fridays, and other days of abstinence, and always from compline till sun- rise the next day.

For a severer solitude, S. Romualdo added a third kind of life, that of a recluse. After a holy life in the hermitage, the superior grants leave to any that ask it, and seem called by God, to live for ever shut up in their cells, never speaking to any one but to the superior when he visits them, and to the brother who brings them necessaries. Their prayers and austerities are doubled and their fasts more severe and more frequent. S. Romualdo condemned himself to this kind of life for several years; and fervent imitations have never since failed in this solitude.

Alban Butler, Lives of the…Saints, vol. 2, pp. 78–79.

The Sacro Eremo or Sant’ Ermo is mentioned by Dante apropos of the death of Buonconte di Montefeltro, slain on the banks of Archiano, a torrent which flows into the Arno, and has its source near Camaldoli:—

Che sovra l’Ermo nasce in Apennino.

born

Above the Hermitage in Apennine.

Dante, Purgatorio 5:95–6. Trans. Longfellow.

View, Poggio Scali (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

One of the highest points of the ridge of the Prato a Soglio is that called Poggio a Scali, which, as Ariosto says—

Scopre il mar Schiavo e ’l Tosco

Dal giogo, onde a Camaldoli si viene.

May Tuscan and Schavonian sea explore,

There, whence we journey to Camaldoli.

Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando Furioso, vol. 1, iv, xi, p. 51.

The view is certainly one of the finest in this part of Italy. Schellfels declares that the houses of Forli, Cesena, and Ravenna are visible from this mountain.

Dante certainly climbed the summit of Falterona; it is on this summit, from which we embrace the whole valley of the Arno, that the poet makes one read the singular imprecation which he has pronounced against this entire valley. He follows the course of the river, and, advancing, he marks all the places he meets with a fiery invective. The more he walks, the more his hatred redoubles in violence and bitterness. It is a piece of satirical topography of which I know of no other example.

Jean-Jacques Ampère, La Grèce, Rome & Dante, p. 247.

Hence we may

Pursue

The Arno from his birthplace in the clouds,

So near the yellow Tiber’s springing up

From his four fountains on the Apennine,

That mountain-ridge a sea-mark to the ships

Sailing on either sea. Downward he runs,

Scattering fresh verdure through the desolate wild,

Down by the City of the Hermits, and the woods

That only echo to the choral hymn;

Then through these gardens to the Tuscan sea,

Reflecting castles, convents, villages,

And those great rivals in an elder day,

Florence and Pisa.

Samuel Rogers, Italy: A Poem.

It is a wild ride (or rather walk, for the path in places is precipitous) of four hours from Camaldoli to Pratovecchio. The road to Pontassieve ascends by the old castle of Romena, where the poet visited his friend the Ghibelline chieftain, Count Alessandro da Romena. It is mentioned by Dante in the words of Maestro Adamo the coiner:—

Ivi è Romena, là dov’ io falsai

La lega suggellata del Battista,

Perch’ io il corpo suso arso lasciai.

There is Romena, where I counterfeited

The currency imprinted with the Baptist,

For which I left my body burned above.

Dante Inferno 30:73–75. Trans. Longfellow.

Near this is the church where Landino, the first commentator of Dante, is shown as a mummified saint. Lovers of Dante will certainly seek for the Fonte Branda, a thread of water falling into a stone basin in a brick wall, which naturally, and not the fountain of Siena, is that alluded to by Maestro Adamo when, tormented by the thirst of hell, he says that he would rather see his seducers brought to the same suffering than himself be refreshed by the clear waters of his home.

Per Fonte Branda non darei la vista.

For Branda’s fount I would not give the sight.

Dante Inferno 30:78. Trans. Longfellow.

Hence we look down upon the whole valley of the Casentino, and—

Li ruscelletti, che de’ verdi colli

Del Casentin discendon giuso in Arno,

Facendo i lor canali e freddi e molli,

Sempre mi stanno innanzi, e non indarno.

The rivulets, that from the verdant hills

Of Cassentin descend down into Arno,

Making their channels to be cold and moist,

Ever before me stand, and not in vain;

Dante Inferno 30:64–67. Trans. Longfellow.

who thence addressed a letter upbraiding the Florentines for resisting the Emperor—“Scritta in Toscana sotto la fonte d’Arno, 11 Avrile, 1311” [Written in Tuscany under the Arno spring, 11 April, 1311],” and one tradition holds that he was in durance here.

A pleasant day’s excursion from Florence may be made by taking the train to Pontassieve, and a carriage thence down the valley of the Arno to Sicci, where the torrent of that name enters the Arno. Hence you follow the Sicci to its source, keeping the valley for five miles farther to the fortress of Castel Lobaco, beneath which is the church of S. Martino in Baco, on a cypress-crested rock with a glorious view. A path ascends from the fortress of Lobaco to the sanctuary of La Madonna del Sasso, whence a path, below the east wall of the church, leads to cave wherein the S. Bridget (c. 874) lived after the death of her brother Andrew at S. Martino a Mensola, and where she died.

The drive from Pontassieve to Florence has much beauty, and follows the windings of the Arno, lying in the low bed which Dante calls

La maladetta e sventurata fossa.

This maledict and misadventurous ditch.

Dante Purgatorio 14: 51. Trans. Longfellow.

It may have been from this road that Michelangelo, as he rode away to Rome for work on S. Peter’s, turned round, and, beholding the red dome of the cathedral in the grey of morning, exclaimed, “Come te non voglio, meglio di te non posso.” [Like thee I will not, better than thee I cannot.]

Podesta. —Supreme officer of state elected by the citizens annually in place of the earlier Consuls, from c. 1200.

Le Arti. —The Guilds; divided into Maggiori and Minori; seven and fourteen. Each had its gonfalone or standard, its coat of arms, and its depot. Every citizen was enrolled in one of these.

Proconsolo. —A sort of Solicitor-General to the Guilds.

Il Bargello. —The High Sheriff or Executor of Justice; usually a non-Florentine Guelf. Later on the State-gaoler.

Gonfaloniere Di Giustizia. —Always a Florentine. The standard-bearer of the people and summoner; in later days of the Republic virtually the head of the Signoria, and President of the Priori.

Signoria. —The governing body of Florence, composed of the Priori delle Arti.

Priori. —Eight in number, two from each quarter of Florence.

Buonomini. —Twelve in number, coadjutors to the Priori, and holding office for three months.

Grandi. Nobles.

Popolani. —Citizens and tax-payers, belonging to the Guilds.

Popolo Minuto. —Small, but enfranchised tradesfolk.

Plebe. —Lower classes; non-tax-paying, and ineligible to office.