Preface & Introductory

Augustus J. C. Hare

Preface

IN 1875 almost all the places described were carefully revisited, in order to make the information they contain…as correct as possible up to the present time. But in giving to others what has been at once the companion and employment of many years, I am only too conscious of the imperfections of my work—of how much better descriptions might be given, of the endless amount which remains unsaid. Bearing Italy ever in my heart, I can only hope that others…will be led to drink at the great fountain which it is impossible to exhaust, though those who have once been refreshed by it, will always long to return.

The Illustrations, with very few exceptions, are from my own sketches taken on the spot, and transferred to wood by the kindness and skill of Mr. T. Sulman.

Augustus J. C. Hare, Holmhurst, January 1876

Introductory

THE old days of Italian travel are already beginning to pass out of recollection—the happy old days, when with slow-trotting horses and jangling bells, we lived for weeks in our vetturino carriage as in a house, and made ourselves thoroughly comfortable there, halting at midday for luncheon, with pleasant hours for wandering over unknown towns, and gathering flowers, and making discoveries in the churches and convents near our resting-place. All that we saw then remains impressed upon our recollection as a series of beautiful pictures set in a frame-work of the home-like associations of a quiet life which was gilded by all that Italian loveliness alone can bestow of its own tender beauty. The arrangements of vetturino travel warded off the little rubs and collisions and discomforts which are inevitable now, and the mind was left perfectly free to drink in the surrounding enjoyment. The slow approach to each long-heard of but unseen city, gradually leading up, as the surroundings of all cities do, to its own peculiar characteristics, gave a very different feeling towards it to that which is produced by rushing into a railway station—with an impending struggle for luggage and places in an omnibus—which, in fact, is probably no feeling at all. While, in the many hours spent in plodding over the weary surface of a featureless country, we had time for so studying the marvellous story of the place we were about to visit, that when we saw it, it was engraved for ever on the brain, with its past associations and its present beauties combined.

Still, there is much to be grateful for in the convenience of modern travel, and indeed many who could not otherwise explore Italy at all, are now, by its network of railways, enabled to do so.

First, we have the rich Arno valley, with its visions of old convents, and castles with serrated towers, standing on the crests of hillsides covered with a wealth of olives and peach-trees, and themselves shut in by ravines of hoary snow-tipped mountains;—of villages and towns of quaint houses, all arches and balconies, with projecting tiled roofs stained golden with lichen, and with masses of still more golden Indian com hanging from the railings of their outside staircases.

Not to be disappointed in Italy as in every thing else, it is necessary not to expect too much, and hurried travellers generally will be disappointed, for it is in the beauty of her details that Italy surpasses all other countries, and details take time to find out and appreciate. But when we once leave general forms to consider details, what a labyrinth of glory is opened to us, where, instead of the rugged outlines and expressionless features of our mediaeval architects and painters, we have the delicate workmanship of a Nino or Giovanni Pisano, or the inspiration of a Fra Angelico or an Orcagna. In almost every alley of every quiet country town, the past lives still in some lovely statuette, some exquisite wreath of sculptured foliage, or some slight but delicate fresco, a variety of beauty which no English architect or sculptor has ever dreamed of, and which to English art in all ages would have been simply unattainable. Most beautiful of all, perhaps, are the tombs, for the Italians of the Middle Ages never failed to enshrine their dead in all that was loveliest and best.

Those who would carry away the pleasantest recollections of Italy should also certainly not sight-see every day. [T]he sight-seeing days will become all the more profitable from having interludes, when it is not necessary to give oneself a stiff neck over staring at frescoed ceilings, and to addle one’s brain by walking through miles of pictures and hundreds of churches, without giving oneself time to enjoy them. Oh no, by all means digest what you have seen; take a fresh breath, think a little what it has all been about, and then begin again.

Another thing which is necessary—most necessary—to the pleasure of Italian travel, is not to go forth in a spirit of antagonism to the inhabitants, and with the impression that life in Italy is to be a prolonged struggle against extortion and incivility.

Nothing can be obtained from an Italian by compulsion. A friendly look and cheery word will win almost anything, but Italians will not be driven, and the browbeating manner, which is so common with English and Americans, even the commonest facchino regards and speaks of as mere vulgar insolence, and treats accordingly. Travellers, however, are beginning, though only beginning, to learn that difference of caste in Italy does not give an opening for the discourtesies in which they are wont to indulge to those they consider their inferiors in the north. Unfortunately they do not always stay long enough to find this out, and the bad impression one set of travellers leaves, another pays the penalty of.

With every year which an Englishman passes in Italy, a new veil of the suspicion with which he entered it will be swept away, only it is a pity that his enjoyment should be marred at the beginning. Englishmen are apt, and chiefly on religious subjects, to accept old prejudices as facts, and to judge without knowledge. Especially is it impossible for “Protestants” to assert, as they so often do, the point where simple reverence for a Cross and Him who hung upon it becomes “Idolatry.”

It cannot be too much urged, for the real comfort of travellers as well as for their credit with the natives, that the vulgar habits of bargaining, far too frequently inculcated by hand-books, are greatly to be deprecated, and only lead to suspicion and resentment. Italians are not a nation of cheats, and cases of overcharge at inns are most unusual,

Those who have travelled in Italy many years ago will observe how greatly the character of the country has changed since its small courts have been swept away. With the differences of costume and of feeling, the old proverbs and stories and customs are gradually dying out. Travellers will view these changes with different eyes. That Venice and Milan should have thrown off the hated yoke of Austria and united themselves to the country to which they always wished to belong, no one can fail to rejoice, and the cursory observer may be induced by the English press, or by the statements of the native mezzo ceto, who are almost entirely in its favour, to believe that the wish for a united Italy was universal. Those who stay longer, and who make a real acquaintance with the people, will find that in most of the central states the feeling of the aristocracy and of the contadini is almost universally against the present state of things. Not only are they ground down by taxes, which in some of the states, especially in Tuscany, were almost unknown before, but the so-called liberal rule is really one of tyranny and force.

The abolition of the religious institutions has also been grievously felt throughout the country, and there are few even of the friends of Italian unity who have not had personal reason to experience its injustice. When “Days near Rome” appeared, one of the Reviews regretted that its author should not rejoice that Italians were no longer called upon “to support swarms of idlers in vestments, and hordes of sturdy beggars in rags.” This is exactly what Italians, with regard to the old ecclesiastical institutions, were not called upon to do. The convents and monasteries were richly endowed; they had no need of being supported. It was, on the contrary, rather they who supported the needy, the sick, the helpless, and the blind amongst the people, who received their daily dole of bread and soup from the convent charities. When the marriage portions of the nuns were stolen by the Government, there was scarcely any family of the upper classes throughout Central Italy which did not suffer; for almost all had a sister, aunt, or cousin “in religion,” upon whom a portion of 1,000l., 5,000l., or 10,000l., had been bestowed, and who was thrown back helpless upon their hands, her fortune confiscated, and with an irregularly paid pension of a few pence a day, quite insufficient for the most miserable subsistence. The English press is slow to see the injustice of these things when it affects other nations.

Those who declaim so loudly upon the advantages of Italian unity are often unaware of the extreme difference which exists between the people and the language in the North and South of Italy—that a Venetian would not in the least be able to understand a Neapolitan and vice versâ. This difference often comes out when the absurd red-tapeism of the Government is put into action.

Where the natives have suffered, foreigners have reaped many advantages from the union in the absence of wearisome custom-houses and requests for passports, and, even more in the ease afforded by the universal coinage, though it has made things more expensive.

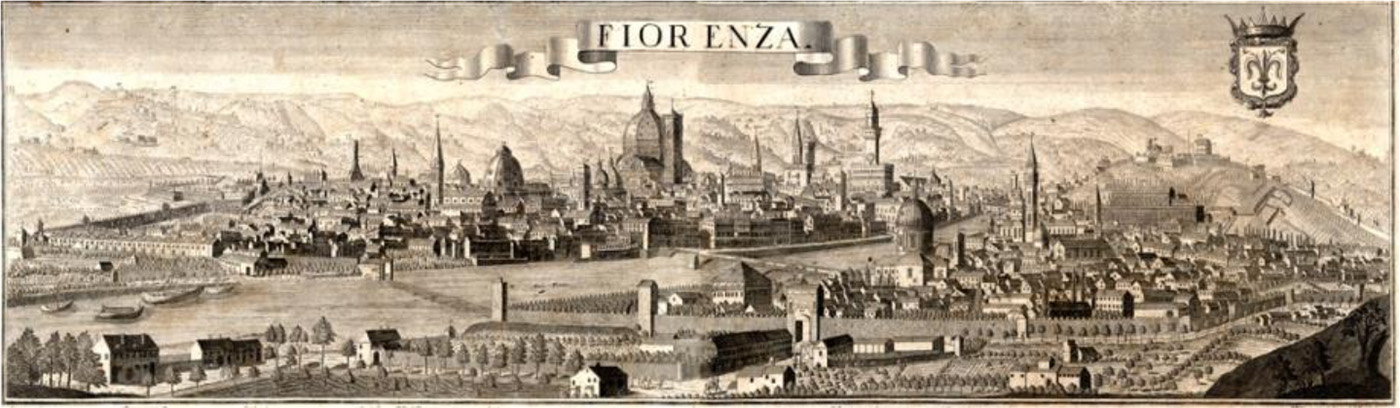

The characteristics of the great Italian cities are well summed up in the proverb: “Milano la grande, Venezia la ricca, Genova la superba, Bologna la grassa, Firenze la bella, Padova la dotta, Ravenna l’antica, Roma la santa.”1Milan the great, Venice the rich, Genoa the proud, Bologna the fat, Florence the beautiful, Padua the learned, Ravenna the ancient, Rome the holy. They are wonderfully different, these great cities, quite as if they belonged to different countries, and so indeed they have, for there has been no national history common to all, but each has its own individual sovereignty; its own chronicle; its own politics, domestic and foreign; its own saints, peculiarly to be revered—patrons in peace, and protectors in war; its own phase of architecture; its own passion in architectural material, brick or stone, marble or terra-cotta; often its own language; always its own proverbs, its own superstitions, and its own ballads.

The smaller towns repeat in extreme miniature the larger cities to which they have been annexed by rule or alliance. Thus the characteristics of Udine and Vicenza repeat Venice, and Pistoia and Prato repeat Florence.

The history of Italy, owing to the complete individuality of its different states, which never have been nominally united till a few years ago, and never have been sympathetically united at all, is chiefly interesting when it treats of internal questions. The different invasions of foreign nations serve only as great historic landmarks amid all that has to be told and learnt of the dealings of the various Italian States and their rulers with each other. Of these, in the fifteenth century, there were twenty petty states, most of them with tyrants of their own, and all these fought with each other.

All the life of the nineteenth century seems to be confined to the greater cities. The smaller cities live upon their past. Each house where a great man lived, each famous event which occurred there, is marked by an inscription, so that the chronicle of the city is written on its own stones; and in the buildings, and the habits and feelings of the people, one seems to be living still in the fifteenth century, lighted by the sunshine of today.

The pictures and buildings of these otherwise forgotten places will always keep them in the recollection of the world, and it is only these which attract strangers to them now; but the traveller who will throw himself into the subject will find unfailing interest and pleasure in seeing how the natural features and opportunities of the place are always repeated in the works of all its eminent artists.

It is a fact more universally acknowledged than enforced or acted upon, that all great painters, of whatever school, have been great only in their rendering of what they had seen or felt from early childhood; and that the greatest among them have been the most frank in acknowledging this their inability to treat anything successfully but that with which they had been familiar. The Madonna of Raffaelle was born on the Urbino mountains, Ghirlandajo’s is a Florentine, Bellini’s a Venetian; there is not the slightest effort on the part of any one of these great men to paint her as a Jewess.

John Ruskin, Modern Painters, vol. 1, p. 121.

The quantity of pictures in the Italian churches and galleries is so enormous that as a rule only the best works are mentioned. There are scarcely any good modern works of art in Italy (the pictures of Benvenuti in the cathedral of Arezzo are an exception), but the way in which art is followed up in Italy is at least continuous and regular, and recalls the remark of Scipione Maffei, that “if men paint ill in Italy, at least they paint always.”2Verona lllustrata.

Those who cannot admire any architecture which is not gothic will be disappointed with what they find in Italy, and, regardless of style, the exterior of most Italian churches is really very ugly. Gothic architecture was introduced into Italy from Germany, and Tedesco is the name it bore and bears. But it was soon “adapted” to the Italian taste, Arnolfo (1294) being the first great operator, and after the dome, which is to be found in no real gothic cathedral (and of which the Pantheon is the only pagan example in Italy) was added… all the rude severity of the northern minster began to disappear under a delicate display of sculpture, and the vagaries of fantastic art, which seemed more suited to the soft skies and pellucid atmosphere.

The real glory of the Italian towns consists not in their churches but in their palaces, in which they are unrivalled by any other country. The most magnificent of these are to be found in Florence, Venice, and Genoa. The greatest palace-architects, amongst many, have perhaps been Vignola, Baldassare Peruzzi, Bramante, Leon-Battista Alberti, Sanmichele, and Palladio.

Turning from towns to the country districts, the vine-growing valleys of Tuscany are perhaps the richest and the happiest, as well as the most beautiful:—

No northern landscape can ever have such interchange of colour as these fields and hills in summer. Here the fresh vine foliage, hanging, curling, climbing, in all intricacies and graces that ever entered the fancies of green leaves. There the tall millet, towering like the plumes of warriors, whilst amongst their stalks the golden lizard glitters. Here broad swathes of new-mown hay, strewed over with butterflies of every hue. There a thread of water runs thick with waving canes. Here the shadowy amber of ripe wheat, rustled by wind and darkened by passing loads. There the gnarled olives silver in the sun, and everywhere long the edges of the corn and underneath the maples, little grassy paths running, and wild rose growing, and acacia thickets tossing, and white convolvulus glistening like snow, and across all this confusion of foliage and herbage, always the tender dreamy swell of the far mountains.

Ouida, Pascarèl, vol. 2, pp. 242–43.

The Contadini of Tuscany are a most independent and prosperous race, who have their own laws for home government, which answer perfectly. The land is all let out by the padrone to the contadino, who is hereditary on the estate, upon the Mezzaria system (from meta, mezzo) by which half the produce of all kinds is given to the padrone, the contadino meanwhile paying no rent, being liable to no taxes, and the padrone supplying everything except the labour. The contadino receives no wages from his padrone, but, according to the rules of the different fattorie, is in addition compelled to supply so many days’ labour for him personally, either with oxen or without. From every contadino when a pig is killed, one ham is given to the padrone. Every contadino also pays a tribute of three or four fat capons at Easter. The “Droit de Seigneur,” which actually existed in Tuscany till late years, is now abandoned, but no contadino can many without the consent of his padrone, and a padrone can insist and often does so, upon his contadino marrying.

The “families” of the contadini are by no means necessarily related to one another, though they live in the same house, and dwell perfectly harmoniously together. Six or seven families often live together under the same heads with the most perfect unanimity. If one of the number is ill, he is always looked after by the rest before they go out to work, and if one becomes maimed or helpless, he is never deserted by his “family” even if they are in no way really related. The women are chiefly occupied about their home duties, but they also have to cut the grass for the beasts. In a vintage, also, everyone works; in the olives only the men.

Bachi, or silk-worms, are a subject of the most vital importance. As the tiny worms grow bigger, every hand, from that of an Italian country-loving marchesa to that of the smallest contadino, is employed in their behalf. The men are busied on ladders in gathering into great sacks the leaves of the gelsi, or white mulberries, which, with the exception of the sweet chestnuts, are the only trees Italians care to cultivate. The whole time of the women is taken up in feeding the creatures, and the amount they eat is simply stupendous. The upper story of a contadino’s house, or of one wing of a palazzo, is usually given up to them.

When the bachi are done with, it is time to think about the vintage, and then come the olives. It is no wonder that Italian contadini have no time to care for the cultivation of flowers such as one sees in English cottage gardens—a bush of roses and another of rosemary generally suffices them, indeed, for all flowers which have no scent, they have the utmost contempt—“fiore di campagna.” Every spare moment is given by a Tuscan woman to straw plaiting, and the girls are allowed to put by the money earned in this way for their dowries. In the winter the men are employed in pruning the gelsi and in cutting the vines down to the ground, in accordance with the Tuscan proverb— “Fammi povero, e ti farò ricco” [Make me poor, and I’ll make you rich].

Attached to all the principal villas is a church or chapel with the priest’s house adjoining it. The contadini almost always go to pray before beginning their work. When the crops are beginning to mature, the priest followed by the fattore and the whole body of the contadini, male and female, walk for several days at 6 a.m. round all the boundaries of the parrócchia [parish], singing a litany. It is the same litany which is represented in the eleventh canto of Tasso as being sung before the walls of Jerusalem.

There are very few good books of general Italian travel. Valery in French, and Forsyth in English, continue to be the best. The latter, which struck Napoleon so much by its perfection of style, that its author obtained his release from captivity, is incomparable as far as it goes, but it is terribly short. Little, except classical quotations, can be gained from the ponderous volumes and stilted language of Eustace. Goethe wrote a volume of travels in Italy; but then, as Niebuhr says, “he beheld without love.”3Barthold George Niebuhr, Letter to Savigny, Feb. 16, 1817. Life and Letters, vol. 2, p. 93. The full quote: “Of Florence I will say nothing,—not even wonder how any one could hasten through it in such a way,—nor yet of his omitting to see the waterfall of Terni. I say all this merely to prove my assertion that he [Goethe] has beheld without love.” Lately Taine, Gautier, and others have given to the world some pleasant Italian gleanings: many delightful descriptive passages may be found in the novels of “George Sand,” and no traveller should leave unread Mr. J. A. Symonds’s enchanting Sketches in Italy and Greece. But for Italy in general there is wonderfully little to read.

In English, too, especial places in Italy have been well attended to; Lord Lindsay’s delightful volumes are perhaps especially full on the art of Pisa and Siena. Florentine travellers will have found their “walks” somewhat elucidated by the volumes of Miss Horner, and may have been able to pick something out of Trollope’s History of the Commonwealth of Florence, even if they are unable to read the Marchese Gino Capponi’s two most useful and intensely interesting volumes on La Storia della Repubblica de Firenze. The incomparable novel of Romola, and the vividly picturesque though very verbose Pascarèl should be read at Florence. Dumas’ Une année à Florence will also be found very amusing. Other pleasant books to be read in Italy are L’ltalie and Les Monastères Benedictins of Alphonse Dantier. The Corinne of Madame de Staël should not be forgotten, or I Promessi Sposi of Manzoni, while I Miei Ricordi of Massimo Azeglio, not only contains many charming pictures of Italian existence, but is interesting as being the first work of any importance written in Italian, not stilted and heroic, but as it is spoken in daily life.

Far the best guide-books are those of Dr. Th. Gsell-fels, both as regards their style, their information, and, above all, their accuracy. The historical paragraphs which are affixed to the accounts of the towns in these volumes are most interesting, and the maps are invaluable. The French guide-books of Joanne are also admirable in many ways. The small hand-books of Baedeker are excellent, carefully corrected, full of practical knowledge, and most useful to the hurried traveller. The architectural student will be glad to have his recollections awakened by the pictures in Gally Knight’s magnificent work on The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Italy from the Time of Constantine to the Fifteenth Century. Much also may be learnt by the study of Street’s Brick and Marble in the Middle Ages, and from a series of articles on the Italian towns which have appeared from time to time in the pages of the Saturday Review.

For the sculpture of Italy, the admirable works of C. C. Perkins, Italian Sculptors and Tuscan Sculptors, should be carefully studied, and are most interesting. The History of Sculpture and the History of Art, by Wilhelm Lübke, translated by F. E. Bunnètt, are also useful, though perhaps more so from their many engravings than from their letter-press. The art-student will read Kugler’s Handbook of Painting, edited by Sir Charles Eastlake, and will, of course, be familiar with Vasari’s Lives of the Painters,—indispensable, though often incorrect—and with Lanzi’s History of Painting. He will also find the ponderous Histories of Painting, by Crowe and Cavalcaselle, very useful for reference, and will refresh himself with M. F. A. Rio’s Poetry of Christian Art.

It is unnecessary to give any “Tours” here. The author would only again advise those who are hurried not to seek to see too much: and if they have not time for more, to see rather those places which are related to one another, and illustrate one course of history and one school of art, than to seek to see many great towns in scattered directions, with a confused recollection of many histories and many schools; the traveller who wishes to make Florence his centre should see at least Prato, Pistoia, Lucca, Pisa, Volterra, S. Gimignano, and Siena, and, if he is healthy and strong, should endeavour to visit the monasteries of the Casentino, especially La Vernia.

The Author would again urge that it is always better to omit than condense—to see something thoroughly.