Chapter I: Useful Information and Historical Outline

Of all the fairest cities of the earth,

None is so fair as Florence. ‘Tis a gem

Of purest ray; and what a light broke forth

When it emerged from darkness! Search within,

Without; all is enchantment! ‘Tis the Past

Contending with the Present; and in turn

Each has the mastery.

Samuel Rogers, Italy: A Poem, “Florence.”

At Pisa we say “How beautiful”: here we say nothing: it is enough if we can breathe.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Letters, vol. 1, p. 331.

Painters:

Gio. Cimabue (c. 1240–1302)

Giotto di Bondone (1276–1337)

Andrea Orcagna (c. 1369)

Amb. Lorenzetti (c. 1348)

P. Lorenzetti (c. 1350)

Taddeo Gaddi (c. 1300–1366)

Lorenzo Monaco (c. 1370–1475)

Simone Martini (c. 1285–1344)

Spinello Aretino ( –1410)

Masolino (1384 (?) –1447)

Masaccio (1402–1429)

Paolo Uccello (1397–1475)

Andrea del Castagno (1396–1457).

Gentile da Fabriano (c . 1370–c. 1450).

Fra Angelico (1387–1455).

Benozzo Gozzoli (1420–1498)

Lippo Lippi ((?) 1412–1469)

Filippino Lippi (1457–1504)

Sandro Botticelli (1447–1510)

Piero di Cosimo (1462–1521)

Dom. Ghirlandajo (1449–1497)

A. Mantegna (1431–1506)

Luca Signorelli (1441–1523)

P. Perugino (1446–1524)

B. Pinturicchio (1454–1513)

Fra Bartolommeo (1475–1517)

M. Albertinelli (1474–1515)

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

Raffaello Sanzio (1483–1520)

Vasari (1511–1574)

Architects and Sculptors:

Arnolfo del Cambio (1240–1310)

Giotto (1276–1337)

Andrea Pisano (c. 1273–1349)

Franc. Talenti (c. –1395)

Giov. di Lapo Ghini (fl. 1345–1357)

Simone di Fr. Talenti (c. –1395)

Taddeo di Ristoro (fl. 1330)

Benci di Cione ((?) c. 1350–1400)

Giov. di Fetto ((?) 1340–1380)

Andrea Orcagna (1308–1369)

Lorenzo di Filippo (fl. 1382–1390)

Michele di Giovanni (fl. 1380–1390)

Nicolo di Piero (di Arezzo) (c. 1360– 1444)

Antonio di Banco ((?) –1415)

Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455)

Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446)

Michelozzo (1396–1482)

Leone. B. Alberti (1405–1472)

Donatello (1386–1466)

Luca della Robbia (1399–1482).

Bern. Rossellino (1409–1464)

Ant. Rossellino (1427–1478)

Desiderio da Settignano (1428–1464)

Mino da Fiesole (1431–1484)

Vecchietta (1410–1480)

Giuliano di Maiano (1432–1490)

Benedetto di Maiano (1442–1497)

G. di San Gallo (1445–1516)

Ant. di San Gallo (1455–1534)

Andrea della Robbia (1435–1525)

Cronaca S. del Pollaiuolo (1457–1508)

Andrea Verocchio (1435–1488)

Jacopo San Sovino (1477–1570)

Michel Angelo (1475–1564)

Benv. Cellini (1500–1571)

Gian Bologna (1524–1608)

B. Ammanati (1511–1592)

B, Bandinelli (1493–1560)

R. di Montelupo (1505–1567

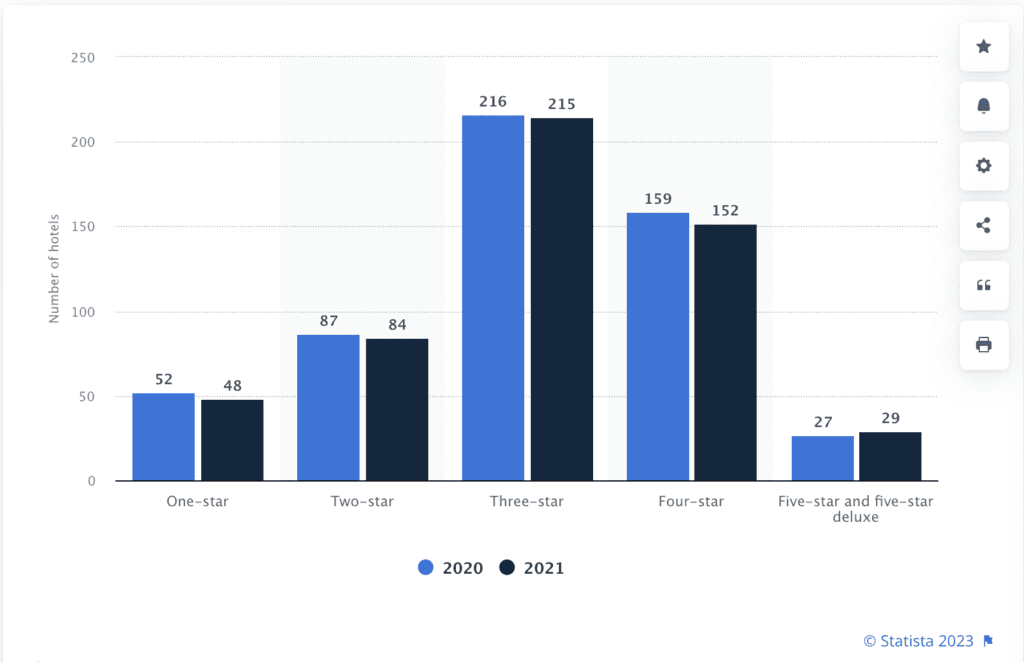

Hotels. In Italy the government ranks hotels based on standardized criteria according to a star system with one star being the lowest and 5 the highest. The criteria can vary somewhat between regions, but within a given province or city the criteria applied to all hotels should be the same. Comparing 2020 and 2021, Statista found that the total number of hotels in Florence remained relatively constant as shown in the graph:

The Covid-19 pandemic and the national lockdown during 2020 greatly limited the number of visitors to Florence. According to Statista: “Overall, the volume of overnight stays by inbound and domestic tourists in Florence totaled nearly 5.4 million in 2021, rising by 60 percent compared to 2020 but only accounting for roughly a third of the figure reported in 2019.”1Statista

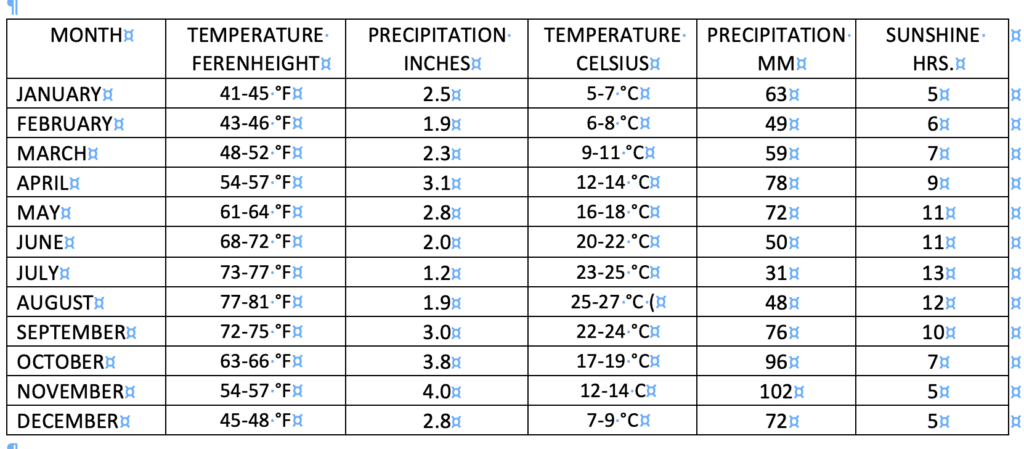

Visitors should bear in mind that High Season runs May through September and that reservations for hotels, restaurants, and museums need be made in advance. The spring and fall Shoulder Seasons are also crowded, but not to the same degree. The winter months represent the Low Season.

Obviously this website cannot list all the hotels in each category. Nevertheless the following selection should provide value in each star category. As a convenience, links to each establishment’s reservation desk is provided. Note that Florence on Foot does not receive a commission if you make a reservation through this site although each hotel has paid for the listing.

★★★★★

The St. Regis Florence

Bernini Palace

Portrait Firenze – Lungarno Collection

Il Tornabuoni The Unbound Collection by Hyatt

★★★★

Brunelleschi Hotel

Grand Hotel Baglioni

Grand Hotel Cavour

Grand Hotel Minerva

★★★

Hotel Paris

Hotel Silla

General Aspect

THE radiant loveliness of the mountain land immediately around Florence renders it the most delightful of all Italian cities for a spring and early summer residence, and no one who has once seen the glorious luxuriance of the flowers which fill its fields and gardens, and lie in desired masses for sale on the broad grey basements of its old palaces, can ever forget them. May is perhaps the most perfect month for Florence, when there are roses inside the house, and outside it the soft hum of the cathedral bells. In winter the frost-fingered winds from the Apennines blow down the valley of the Arno, biting like the wolves of yore. Forsyth mentions that physicians say they can scarcely conceive how people live at Florence in the winter or how they can die there in summer.

Florence, “La bellissima e famosissima figlia di Roma” [The most beautiful and most famous daughter of Rome. Dante Convivio, 1:3,4.] as Dante calls her, was, until 1888, less modernised than Rome has been since the change of Government, though, during the short residence here of the King’s court, the magnificent old walls of Arnolfo, one of the glories of the town, were destroyed, to the great injury of the place, with the towers which Varchi described as “encircling the city like a garland.”2Some of these were demolished in 1527. Benedetto Varchi, Storia Fiorentina, vol. 1, p. 96. “le torri, le quali a guisa di ghirlanda le mura di Firenze intomo intomo incoronavano.”

Conservatism was, till recently, a prominent element in Florentine character, and there is scarcely the site of an old building or a house once inhabited by any eminent person which is not marked by an inscription. Even the paving-stones in many streets have adhered to a polygonal style since A.D. 1240, when Messer Rubaconte is said to have introduced it from Milan. But there are two very distinct styles of paving here. In the last few years, however, building speculations, encouraged by a commercial Municipality, have done as much as possible to destroy the harmonious beauty of the place.

THE radiant loveliness of the mountain land immediately around Florence renders it the most delightful of all Italian cities for a spring and early summer residence, and no one who has once seen the glorious luxuriance of the flowers which fill its fields and gardens, and lie in desired masses for sale on the broad grey basements of its old palaces, can ever forget them. May is perhaps the most perfect month for Florence, when there are roses inside the house, and outside it the soft hum of the cathedral bells. In winter the frost-fingered winds from the Apennines blow down the valley of the Arno, biting like the wolves of yore. Forsyth mentions that physicians say they can scarcely conceive how people live at Florence in the winter or how they can die there in summer.

Florence, “La bellissima e famosissima figlia di Roma” [The most beautiful and most famous daughter of Rome. Dante Convivio, 1:3,4.] as Dante calls her, was, until 1888, less modernised than Rome has been since the change of Government, though, during the short residence here of the King’s court, the magnificent old walls of Arnolfo, one of the glories of the town, were destroyed, to the great injury of the place, with the towers which Varchi described as “encircling the city like a garland.”3Some of these were demolished in 1527. Benedetto Varchi, Storia Fiorentina, vol. 1, p. 96. “le torri, le quali a guisa di ghirlanda le mura di Firenze intomo intomo incoronavano.”

Conservatism was, till recently, a prominent element in Florentine character, and there is scarcely the site of an old building or a house once inhabited by any eminent person which is not marked by an inscription. Even the paving-stones in many streets have adhered to a polygonal style since A.D. 1240, when Messer Rubaconte is said to have introduced it from Milan. But there are two very distinct styles of paving here. In the last few years, however, building speculations, encouraged by a commercial Municipality, have done as much as possible to destroy the harmonious beauty of the place.

Building anew, as though upon a barren land, without regard either to the architecture of the quarter, or any attention to the memories and associations of the past.

(Pietro??) Franceschini.

Endless buildings of interest have been swept away or are doomed to destruction, and, not content with that, the too-well-known municipal insect has attacked the nomenclature of the historic streets, as in other illustrious cities. Instead of being makers of History the House of Savoy has been led by fawning municipalities to destroy and sweep much of it away.

The ancient towers of the Amidei, the superb groups of the Piazza S. Biagio; the residence of the Arte della Seta, that of the Arte dei Rigaturi, and that of the Arte dei Linaioti, the house of the Lamberti, the palace of Dante di Castiglione, the towers of the Caponsacchi and the Ubaldini, the house and towers of the Amidei; two noble palaces of the Sassetti; the Anselmi, the Vecchietti, and the Buondelmonti palaces; the column of Santa Trinità, the interesting and ancient residences of the Via del Refe Nero and of the Vecchietti; and the mutilation or destruction of the fine XIV. c. palace of the Martelli, between the Via dei Cerretani and the Piazza del Olio, and of the palace of the famous Arte della Lana—all these, one and all, are condemned to destruction by the Municipality of Florence. . . .

It has been reserved for the thankless sons of Florence, of a venal and degenerate time, to efface all that the cannon of the Spaniard spared, all that the German and Frenchman left unharmed.

Ouida.

In few cities was the history of the place written more vividly and effectively upon its stones than in Florence.

Florence existed in Etruscan times; and became a Roman colony; and Christianity is said to have been introduced in A.D. 313, but she never attained great importance until the Middle Ages. Her earliest written records belong to the twelfth century. Giovanni Villani (1300) has not very much to relate regarding her past that is not legendary; and he begins with the tower of Babel, and plunges onwards into universal history, like the Florentine woman in the Paradiso (15:125): —

Favoleggiava con la sua famiglia

De’ Trojani e di Fiesole e di Roma.

Told o’er among her family the tales

Of Trojans and of Fiesole and Rome.

Dante Paradiso 15:125–26. Trans. Longfellow.

Excavations have proven that the Forum of Roman Florence occupied the site of the now vanished Mercato Vecchio; and the amphitheatre that of the Borgo dei Greci. In A.D. 405 the Goths beleaguered her, under Radagasius; from which crisis Stilicho’s arrival with an army relieved her. Toward the end of the following century the Lombards occupied Tuscany; and Professor Villari and others have cited documents which show that in the eighth century Florence had become an annex of Fiesole—the hill that dominated the Roman road or Via Cassia, on which she was situated. But consult Davidsohn’s Geschickte, &c. Certain it is that

at the commencement of the eleventh century the construction of San Miniato al Monte, in addition to other churches built about the same period affords indubitable proof of awakening prosperity and religious zeal, in fact, Florence became one of the centres of the movement in favour of monastic reform. S. Giovanni Gualberto, of Florentine birth, who died in 1073, inaugurated the Reformed Benedictine Order known by the name of Vallombrosa, in which place he founded his celebrated cloister.

Pasquale Villari, First Two Centuries of Florentine History, p. 74.

and again, no fixed year can be assigned to the birth of the Florentine Commune, which took shape very slowly, and resulted from the conditions of Florence under the rule of the last Dukes and Marquises of Tuscany—while her commerce and industry undoubtedly increased during the rule of Countess Matilda (1046–1115)—and even in her days we find the mass of the citizens divided and arranged in groups.

Pasquale Villari, First Two Centuries of Florentine History, pp. 84 & 100.

Villani records that the guild of woollen-cloth refiners, i.e. Calimala, were entrusted in 1150 by the Commune with the construction of San Giovanni; and this Commune was represented by Consuls elected annually from members of various Guilds, which, federated, formed the yet unconsolidated Constitution. It was inevitable that such a growing force as this would come into conflict with, and have to work out its own salvation through conflict with Feudal authority, represented by the Imperial Envoys and Teutonic nobles, who naturally regarded their rights as absolute. The Florence we study was largely the result of this attrition, acutely modified, however, in special directions by her adherence to the side of the Papacy during its long and bitter struggle with the Empire. Florence, in fact, was shaped between the hammer and the anvil, as many other beautiful things have been. Her whole history, complicated as it is, works out in perfect logical sequence, link by link, as she becomes the dominant power in Tuscany, political, the dominant power in Europe, financial; and finally (before her brilliant decline), the dominant power in the world, aesthetic. In 1198 she already stood at the head of a league of the Tuscan towns against Philip of Swabia. But in 1246, when the Emperor Frederick II. favoured the Uberti, who as imperialists were now called Ghibellines, the Guelfs or Buondelmonti faction were expelled from Florence. A hundred years later Dante complains of the changes which Florence strove to introduce in politics and civilisation: —

Quante volte del tempo che rimembre,

Leggi, monete, officii e costume

Hai tu mutato, e rinnovato membre?

How oft, within the time of thy remembrance,

Laws, money, offices, and usages

Hast thou remodelled, and renewed thy members?

Dante Purgatorio 6:145–47. Trans. Longfellow.

Upon the death of Frederick II. in 1250, the Guelfs returned and there was a reconciliation. A military democratic confederation was then formed, called “Primo Popolo.” The six divisions—Sestiere—of the town each chose two burgesses—Anziani—for a year, and, the better to avoid party spirit, two foreigners, one of whom was to serve as Podestà, the other as Capitano del Popolo. The confederation was divided under twenty standards, with an annual change of captains—Gonfalonieri. In battle, the Carroccio, a huge car, drawn by oxen with scarlet trappings, and supporting the standard of Florence, and a bell which was to ring ceaselessly, was to be the great centre and rallying-point. The standard was changed from being a white lily on a red field to the reverse.

When Manfred had gained possession of Naples, the Ghibellines hoped by his assistance once more to obtain the supreme power in Florence, but the Anziani discovered their plot and drove them out of the city. They fled to Siena, where, under Farinata degli Uberti, they completely defeated the Florentine army of the Guelfs in the Battle of Monteaperto, September 4, 1260, captured the Carroccio, and re-entered Florence in triumph. They would even have destroyed the city but for the noble defence of Farinata, who declared that he had only been induced to conduct the war by the hope of returning to his beloved native place. Six bitter years for Florence followed, during which Dante was born. After Manfred, in fighting against Charles of Anjou at Benevento (1266) had lost his life and his kingdom, the Guelfs regained their lost power, and a new democratic Constitution was formed under the invited suzerainty of King Charles (for ten years), who used to appoint the Podestà, and now sent Guy de Montfort with 800 French knights to occupy the city (1267).

The administration became reorganised with the following officials: 12 Anziani—two for each division of the city, aided by 100 Buonomini as a deliberative Council; then a Captain of the People, assisted by a Council of eighty Guelfs, including the Captains of the Arti, or Guilds. To these two separate Parliamentary bodies politic were added the Podestà, appointed by Charles of Anjou, with a Council of ninety, and a general Council of the Commune numbering 300. In 1282 (after certain modifications as well as the expiration of the suzerainty of King Charles), the Guilds, or Arti, led by that of the Calimala, or dressers of foreign cloth, were enabled to elect additional officials as their representatives. These were called Priors, or Priori dell’ Arte; and their official Chapter-house was called the Bocca di Ferro (later the Torre di Dante) adjoining the future Badia, before they removed to the Palazzo Vecchio. A Guelfic Democracy, which disfranchised all nobles who did not enrol themselves in their guilds, and were chronically anti-Ghibelline—thus consolidated the Government of Florence in the hands of the merchants, and it was now that the third and last girdle-wall of the expanding city was built, whose gates alone have been spared to us by the Vandals of 1863. In 1289, the Florentine Guelfs, having established their own power, assisted the popular party at Arezzo in gaining the bloody Battle of Campaldino, June 11, 1289, in which Dante, who had been received into the Guild of Doctors, fought amongst the Guelfic troops. In 1298 the Palazzo della Signoria was built at Florence—per maggior magnificenza e più securità de’ Signori, [for the greater magnificence and security of the Signori] and many other new buildings were erected. Macchiavelli says— “Never was the town in a more happy or flourishing condition than at this time, rich in population, treasure, and aspect; having 30,000 armed citizens, and 70,000 from its territory (suo contado); while the whole of Tuscany was either subject or allied to it.”

The principal families in Dante’s time were the Buondelmonti and Uberti, the Amidei and Donati. A widow of the noble house of Donati being determined to have no other son-in-law than the head of the great family of Buondelmonte, persuaded him to marry her daughter, who was of matchless beauty, while he was actually engaged to one of the Amidei.

When the marriage was known, the Amidei, and their relations the Uberti, fell upon the young Buondelmonte as he was riding across the Ponte Vecchio, and slew him at the foot of a statue of Mars. This murder threw the whole city into confusion, half the citizens siding with the Buondelmonti, half with the Uberti. Dante, in fact, grew up while the Guelf party, to which he belonged by birth, increased in power; albeit it became divided into two sections: the extremes and the moderates. The latter were not hostile to the idea of reconciliation with the Ghibellines, and are identifiable with the Bianchi; while the former tied itself to the Court of Rome and desired the actual extirpation of the Ghibellines. This party acquired the upper hand, and the section to which Dante belonged, which preferred an ideal Emperor to any possible Pope, suffered. The great artists and men of letters were born of these cross-currents, which their lives and talents have since so splendidly illustrated. The inflammable material so abundant was but the natural heritage of ages of disorder and violence, common to every part of Italy, but concentrated in the towns. Out of sanguinary confusion the Genius of Florence eliminated high ideas and imaginings, but the pilot to these was not either the Church nor Feudalism, but practical Commerce. Industrialism triumphed over both until it became metamorphosed into a tyrannous Plutocracy.

Florence had now such power as to fear neither the Empire nor her own exiles, but her strength continued to be wasted by internal strife, and content was not known. Family feuds complicated by trade jealousies, which even a successful war with Arezzo did not allay. “The New Aristocracy, puffed up with wealth and success, were becoming lawless and arrogant; while the popolo minuto (or small enfranchised tradesfolk) were grown strong enough to resist the galling insolence with which they were treated, and to demand a larger share in the Government.” (F. A. Hyett, Florence: Her History and Art, p. 51.). Dino Compagni, in fact, tells us how completely corrupted were both the Guelfic nobility and the Priors. We should also recollect that serfdom had been abolished in 1289. Five years later the Ordinamenti della Giustizia were made law, so as to exclude nobles from the Government, and strengthen the Guilds. Special elements of discord were found in the quarrels of the great family of the Cerchi, who had become powerful through trade, and the noble race of the Donati. The Cerchi adopted the name of Bianchi, the Donati that of Neri, names borrowed from the Ghibelline and Guelfic divisions of neighbouring Pistoia. Both in turn were banished, and it was the anger excited by the recall of the Ghibelline Guido Cavalcanti which led to the banishment of Dante, who was his personal friend, and who was condemned by a Guelfic court, under the influence of Corso Donati, afterwards himself exiled and put to death.

No king of the Romans was proclaimed or came southward to be crowned until 1312. The Ghibellines, or Imperialists, were therefore not held in check by their over-lord; while the Guelfic Communes had no arbiter to appeal to without giving too flattering a power to the Pope.

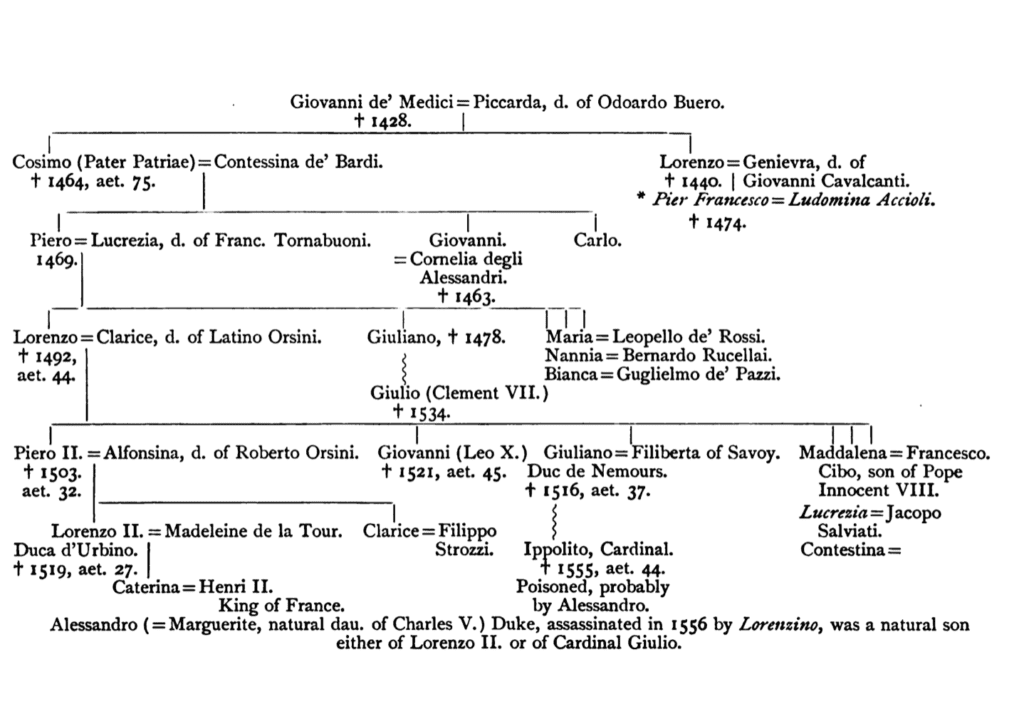

After the death of Charles of Calabria in 1328 (great grandson of Charles of Anjou), whose aggressions had made the foreign Signorie unpopular, foreigners were excluded from the Government, until the successes of his French kinsman, Walter de Brienne, Duke of Athens, as general of the Florentine army, led to his so far gaining the affections of the people that, on September 8, 1342, he was rashly invested by popular acclamation with the sovereignty for life; but his rule of violence and vanity was of short duration, and he was expelled in the following year. In ten months he had extracted 400,000 fiorini from the commonwealth. The Guelfs now returned to power, and strengthened their influence by the benevolence they showed during the great plague of 1348, which is described by Boccaccio (born 1313). The noble family of the Albizzi was now at the head of the Guelfs, and their tyranny was such that the Ghibellines, rather than the Guelfs, became the representatives of the popular party. Such was the case when the Revolution of the Ciompi (Plebs) took place under Michele di Lando (1378) a wool-carder, who was chosen Gonfaloniere, and, in the words of Macchiavelli, “overcame every citizen by his uprightness, cleverness, and kindness, like a true deliverer of his country.” He ruled Florence for only twenty-six hours. The Ciompi, however, were soon expelled, and excluded from the new Signoria, and the Ghibelline family of the Medici, who had risen to wealth under the banker Giovanni de’ Medici, coming forward as patrons of the popolo minuto, began to rise in power in spite of the utmost efforts of the Albizzi, who felt that their star was waning. Giovanni, who died in 1428, left an enormous fortune to his two sons, Cosimo, born 1383, and Lorenzo, born 1394. Both these were banished for a time by the influence of Rinaldo Albizzi; on their recall, Cosimo, who was made Gonfaloniere, gained universal approbation by the magnificence with which his immense fortune enabled him to receive the illustrious guests who came to the Council of Florence in 1439, while his sympathetic intercourse with men of genius led to his being regarded as a typical patron of the arts and sciences. It was at this time that Brunelleschi and Michelozzi graced Florence as architects; Donatello and Ghiberti as sculptors; Masaccio and Filippo Lippi as painters. The enthusiasm of Cosimo for Platonic philosophy led to his founding the famous Platonic Academy of Florence, in which Marsilio Ficino, the son of his physician, was the leading spirit. The wonderful learning of Cosimo in Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, and other languages, brought about the foundation of the Medicean Library, while his love of art led to the decorations of S. Marco by Fra Angelico. In the alliances of his children he thought rather of noble Florentine families than of foreign princes. In the financial world he was the Rothschild of his day, and he was so beloved by the people that shortly before his death the title of Father of his Country was bestowed upon him by a public decree in 1464.

Lorenzo de’ Medici, afterwards called the Magnificent, was only in his sixteenth year when his grandfather Cosimo died, but his brilliant talents and training at once enabled him to take a part in public affairs, and to assist his feeble father Piero, who died five years afterwards. When the rich Luca Pitti (who was then building the Pitti Palace) and others were discovered in a plot to overthrow the Medicean power, he transformed them into friends, acting, in the words of Valori, on the principle that “he who knows how to forgive, knows how to win everything.” At the famous tournament of the Piazza S. Croce (1468), which has been celebrated by Pulci and Politian, both Lorenzo and his brother Giuliano won prizes. Landino wrote a whole book upon the education of the Medici, which was chiefly carried on under Marsilio Ficino; they soon received the name of “principi dello stato” [first citizens].

Lorenzo married, in 1468, a daughter of the Roman family of Orsini. In 1469 his father died, and he was immediately requested to undertake the government of the State. He continued to seek the advice of the wisest counsellors, and then to act independently after mature consideration. He remained bound by the closest friendship to his brother Giuliano. He liberally expended for the benefit of the State the great treasure which he gained from trading speculations all over Europe. His encouragement made Florence at this time the capital of the Arts for the whole world; whilst a visit from Galeazzo Sforza, Duke of Milan, introduced a fashion of display and luxury hitherto unthought of. In 1478, republican fears, mingled with private jealousies, led to the Conspiracy of the Pazzi, who plotted with the Riarii, nephews of Sixtus IV. (whose arrogant claims had been resisted by Lorenzo), to murder both the Medici in the cathedral, and to raise a demonstration of Freedom. Giuliano fell under the dagger of Francesco dei Pazzi as the Host was being elevated, but Lorenzo, though wounded, was able to take refuge in the sacristy. When Jacopo dei Pazzi rushed with shouts of “Libertà” through the streets, no one responded, and the people rose for the Medici, crying “Vivano le palle”4The arms of the Medici were or, five palle, gules: first eleven, then nine, then (Cosimo I.) eight, then (Piero) seven, then (Lorenzo the Magnificent) six. “Il Magnifico” was the courtly expression for almost all great nobles. (the arms of the Medici). The Pazzi and their co-conspirator, the Archbishop of Pisa, were executed. Sixtus IV., furious, having vainly demanded the exile of the Medici, now stirred up the King of Naples against Florence, whereupon Lorenzo, to save the republic, delivered up his person, and gained over his enemy by his magnanimity (“vicit praesentia famam.”—Valori, [fame has conquered the present]). Thenceforward the importance of Florence seemed to glow from Lorenzo as from a radiant centre. Foreign Courts sought not only his alliance, but his advice; even the Sultan placed himself in friendly relations with him, and sent him a giraffe and other strange animals. Commerce flourished, for since Florence had won the harbour of Leghorn from the Genoese in 1421, she had built her own ships, which traded in the ports of Asia Minor, the Black Sea, Africa, Spain, England, France, and Flanders. Until 1480 the galleys all belonged to the State, under the command of an admiral, the State letting them out to the merchants at an assessment.

Florence, become more than ever the metropolis of art and learning, had in 1471 her own printer, Cennini. Greek became the most popular of studies. Scholars, by their readiness of speech, won great weight in all political transactions; literary fame brought riches; and scientific conversation was a power in good society. Even ladies shone as philologists. Lorenzo, instructed by Landino, Filelfo, Ficino, Lorenzo Valla, Poliziano, Sannazzaro, and brought up on the Platonic philosophy, became also a poet: his sonnet, “O chiara stella, che co’ raggi suoi,” [O bright star, that with your rays] is still well known. Amongst the artists he encouraged were Antonio Pollajuolo and Luca Signorelli, the forerunners of Michelangelo, and he founded in the garden of S. Marco an academy for young artists, to which Michelangelo became admitted on the recommendation of Domenico Ghirlandajo. Lorenzo died in his famous Villa Medicea at Careggi, April 8, 1492.

A partial reaction from the extreme luxury in which Florence had been revelling had set in about two years before owing to the sermons of Savonarola, a Dominican monk of S. Marco. His prophecy that chastisement was at hand seemed to be fulfilled under the government of the weak Piero de’ Medici, son of Lorenzo, who purchased the protection of Charles VIII. by the surrender, in 1494, of all the fortified places of the Republic. The disgrace was so keenly felt by Florence that Capponi in the Signoria declared Piero incapable of conducting affairs, and the Medici were expelled from Florence, amid cries of “Abbasso le palle.” [down with the palle (balls=the Medici arms)]

On Nov. 17, 1494, Charles VIII. made a triumphant entry into Florence, but his exactions were restrained by the dignity of the Florentine deputy Capponi. After his departure, Savonarola was made law-giver of Florence. A council of 1000, with a select committee, like that of Venice, but with Christ as their King instead of a doge, was the form of government which he advocated. In 1495, the entire organisation of the State was given up to him as the representative of the “Christocratic Florentine Republic”; his throne being the pulpit. For three years he ruled in a manner which induced even Macchiavelli to acknowledge his greatness. During this time such an inspiration of love and sacrifice breathed throughout Florence, that unlawful possessions were restored wholesale, mortal enemies embraced each other, hymns, not ballads, were sung in the streets, the people received the sacrament daily, and over the cathedral pulpit and over the gate of the Palazzo Vecchio was written—“Jesus Christ is the King of Florence.” The public officials now included—Lustratori (purifiers of worship), Limosinieri (collectors of alms), and Moralisti, who cleared the houses of playing-cards, musical instruments, and worldly books. In 1497 an attempt was made to restore the amusements of Carnival, but the adherents of Savonarola went from house to house collecting the Vanità or Anatema that is, all sensuous books and pictures, which they burnt in Piazza S. Marco on a huge pyramidal pyre on the last day of Carnival amid the blare of the trumpets of the Signory and the songs of the children.

But the true old Florentine spirit wearied of theocratic monkish government, and Alexander VI., indignant at Savonarola’s having dubbed his court the Romish Babylon, excommunicated the monk, who however refused to recognise his prohibition to preach, declaring that “when the Pope orders what is wrong, he does not order it as Pope.” A Franciscan friar now accused Savonarola of heresy, and challenged him to the Ordeal by fire. He consented, but when the day came, the ordeal was postponed by trivial discussions, until a storm of rain extinguished the flames. Then the prophet lost his glory. S. Marco was stormed, Savonarola was taken prisoner, was forced by the torture to confessions which he vainly recanted, and, on Ascension Day, 1498, he was hanged, and afterwards burnt, together with his two principal followers, Fra Domenico and Fra Silvestro, in the Piazza della Signoria.

It was about this time that Amerigo Vespucci of Florence, who gave his name to America, was exploring the coast of Venezuela.5See his portrait in Dom. Ghirlandajo’s fresco, 2nd altar, R., in the Church of the Ognissanti, where, in 1512, he was buried.

Piero de’ Medici had died in exile in 1503, but in 1512 the Dynasty returned to Florence in the person of his son Lorenzo II. and his youngest brother Giuliano. In the same year Giovanni de’ Medici ascended the papal throne as Leo X. Both the Medici who were “restored” died young, Giuliano in 1516, and Lorenzo in 1519, a year after his marriage, leaving an only daughter, Catherine de’ Medici, afterwards the famous Queen of France. Besides this infant, of descendants of Cosimo (Pater Patriae), there only remained Pope Leo X., who was son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, Cardinal Giulio, afterwards Pope Clement VII., son of Lorenzo’s brother Giuliano (killed by the Pazzi), and two illegitimate youths, Alessandro, supposed to be the son of Cardinal Giulio, and Ippolito, son of Giuliano.

The illegitimate Medici were brought up at Florence by guardians appointed by their papal relatives, but after the misfortunes of Clement VII. —called by Ranke “the very sport of misfortune, and without doubt the most ill-fated Pontiff that ever sat upon the papal throne” —the Medici and Passerini, their guardian, were once more expelled from Florence by a revolution under the younger Filippo Strozzi and his wife Clarice, herself the daughter of Piero de’ Medici—the lady who nick-named them “Mules” and declared that the Medici-Riccardi Palace (Lorenzo’s house) should not be their stables.

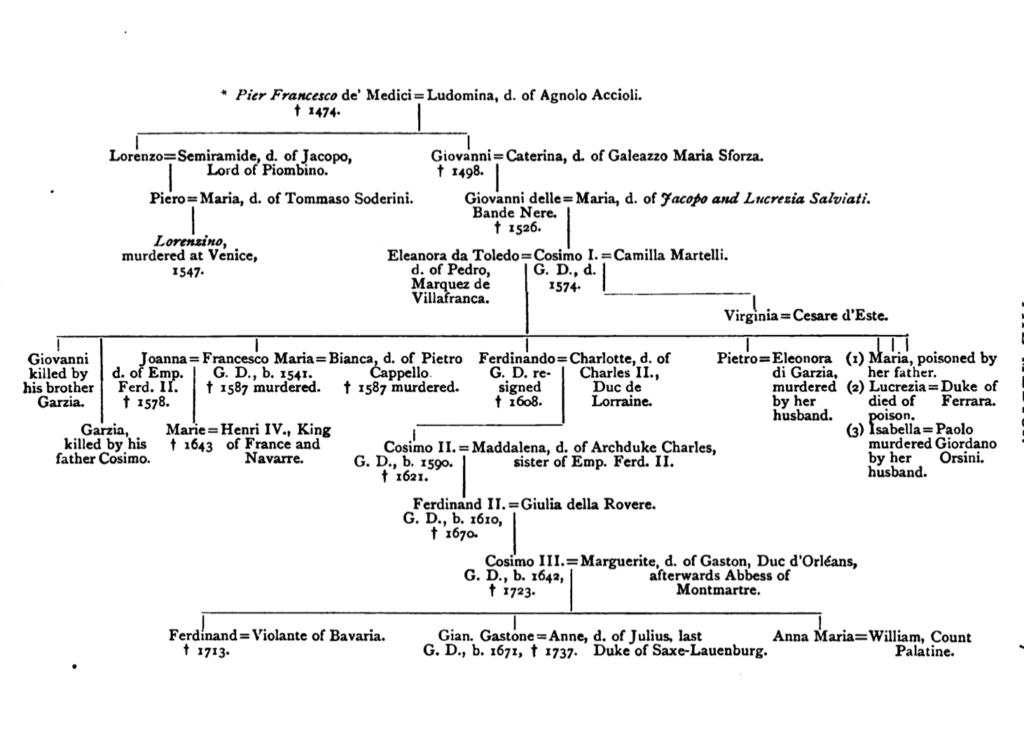

But the family fortunes again turned. Ippolito was created a Cardinal; and in 1529 a league hostile to the liberties of Florence was formed between Clement VII. and the Emperor, Charles V., by which it was arranged that Alessandro should marry Margaret, the illegitimate daughter of the latter. Florence, resolved to resist attack, was fortified by Michelangelo, but succumbed after an eleven-months’ siege, and her republican freedom was finally lost, August 3, 1530, at the Battle of Gavinana in the Apennines, where both the generals, the Prince of Orange and the gallant Ferucci, fell. On July 29, 1531, the imperial envoy announced to the Signoria the Decree which abolished it and made Alessandro de’ Medici hereditary Duke of Florence, under the suzerainty of the Emperor. Alessandro surrounded himself with a body-guard of 1000 men and built a new citadel, but was murdered by his relation Lorenzino in 1537, when Cosimo I., son of Giovanni delle Bande Nere, succeeded in his 18th year, and moved the seat of Government to the Palazzo Vecchio and thence to P. Pitti. Cosimo imitated the great Lorenzo by founding the Academy of Florence and beginning the glorious collections of the Uffizi. In 1569 he was made Grand-Duke by Pope Pius V., and the title was confirmed to his son in 1575 by the Emperor Maximilian II. In 1574 he was succeeded by Francesco I., who married first Joanna of Austria, sister of that Emperor, and secondly, the beautiful Venetian, Bianca Cappello, who had long been his mistress.

In 1587, upon the tragical deaths of both Francesco and Bianca, his brother Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici succeeded, and became distinguished by his war against the Turks and by his popularity. The next sovereign, Cosimo II., who succeeded in 1609, was also distinguished as a protector of art and science. But the prosperity of Florence began seriously to wane under the weak Ferdinand II., and continued to do so under the vain Cosimo III. and the foolish Gian-Gastone, who was the last of the Medici except his sister, widow of the Elector Palatine, whom Gray the poet (1740) describes as “receiving him with much ceremony, standing under a huge black canopy,” and as “never going out but to church, and then with guards and eight horses to her coach.” [Thomas Gray, Works, p. 70.] With this childless princess the family came to an end.

After the extinction of the Medici, in accordance with the conditions of the Peace of Vienna of 1735, Tuscany fell to Duke Francis Stephen of Lorraine (afterwards the Emperor Francis I.), the husband of Maria Teresa. Under his son and grandson it prospered exceedingly. In 1799 the French expelled the Grand-Duke, and in 1801 Tuscany was placed under the Infante Louis of Parma as the kingdom of Etruria; in 1808 it was ceded to France; in 1814 it was given back to the Grand-Duke Ferdinand, whose son Leopold II., raised to the sovereignty in his 18th year, was the great benefactor of the lands of Tuscany, under the ministry of Count Fossombrone. In 1848 the Grand-Duke was compelled to recognise a radical ministry (Guerazzi, Montanelli, Mazzini, Prince Corsini-Lajatico). In 1849 he fled to Gaeta, and for one fortnight Guerazzi ruled as Dictator. Then the Grand-Duke was recalled, imprudently strengthened himself with 10,000 Austrian soldiers, and in 1852 abolished the constitution. In 1859 he was compelled to abdicate. In 1860 Tuscany was incorporated with the kingdom of Victor Emanuel; from 1863 to 1871 Florence was the capital of that kingdom. In 1871 it resigned its position to Rome, and has since then sunk into a provincial city, bereft of the presence of a court. To its Medici princes and their Austrian successors it owes many of its noble buildings, and its incomparable galleries and museums; the reign of Victor Emmanuel is commemorated by the façade of S. Croce, the destruction of the remaining walls which encircled the city, and which made Florence, with the exception of Rome, unique amongst European capitals.

After the death of Florentine freedom in 1530, Art also began to decline at Florence, only finding a noble representative in the sculptor Giovanni da Bologna—properly Jean Boullonge of Douai. The works of the later architects, Buontalenti, Ammanati, &c., and of such artists as Vasari and Allori, do not make us regret that they are few in number in comparison with those of their predecessors.

In Architecture Florence shines especially by her palaces, which with the chief churches and bridges, may be enumerated here, together with their authors: Palazzo Vecchio: (designer) Arnolfo di Cambio (1298); court, Michelozzo (1434). Bargello (1255): court and outside stair, Benci di Cione (1433–45). Duomo (1296): Arnolfo, Giotto, Francesco Talenti. Campanile: Giotto and Talenti (1334). Dome: Brunelleschi (1420–34). Loggia dei Lanzi: Benci di Cione and Simone Talenti (1376). Or San Michele (1337): Taddeo Gaddi, Orcagna, Simone Talenti. Baptistery: (ancient) bronze doors (1330), Andrea Pisano; northern and eastern doors, Lorenzo Ghiberti (1403–47). Palazzo Medici-Riccardi: Michelozzo (c. 1430). Palazzo Strozzi (c. 1470): Benedetto da Maiano and Simone del Pollajuolo. Palazzo Rucellai (c. 1495): Leon-Battista Alberti. Palazzo Antinori (1490?): Giuliano di San Gallo. S. Maria Novella: Fra Ristoro (1279); Fra Jacopo Talenti (1357); façade by Alberti (1470). S. Lorenzo: Brunelleschi (1425). Laurenziana: (designed) Michelangelo. Medicean Chapel (1504): Giov. di Medici. S. Marco: Michelozzo (1437–52). Ognissanti (c. 1560): S. Trinità: Niccolò da Pisa (1250); Buontalenti (1536–1608). S. Croce: Arnolfo di Cambio (1294); Simone del Pollajuolo (1480). Palazzo degli Uffizi: Vasari (1560); tribune, Buontalenti. Loggia dei Pesci: Vasari. Mercato Nuovo: Tasso (1549). S. Maddalena dei Pazzi: Brunelleschi and Giuliano da San Gallo (1479). Palazzo Panciatichi-Ximenes (1490): G. San Gallo. Palazzo Gondi (1481): G. da San Gallo. Palazzo Pitti (1435): Brunelleschi; wings and court, B. Ammanati (1560). Badia (campanile, c. 1350): refashioned 17th cent. Carmine (15th cent, nearly destroyed by fire 1771). S. Spirito (nearly destroyed by fire 1471, restored by Brunelleschi); choir (1599–1608) G. B. Michelozzi. S. Miniato (1013), chapel of S. James (1461): A. Rossellino; sacristy (1387); campanile, Baccio d’Agnolo (1519). Certosa (1341): A. Orcagna. Ponte S. Trinità (1566–69): B. Ammanati. Ponte Vecchio: Taddeo Gaddi (?) (1335). Ponte alla Carraia (1335–1557): Ammanati. Ponte alle Grazie (Rubaconte) (c. 1240): Lapo; damaged 1557, widened since.

The treasures of the Galleries and Museums (including sixteen works attributed to Raffaelle) are inexhaustible, and every taste may be satisfied in them. In the Uffizi and Pitti alone, a walk of miles may be taken on a wet day, entirely under cover, and through avenues of Art-treasures the whole way. When we add to these attractions the proverbially charming, genial character of the Tuscan people, we feel that it would be scarcely possible to find a pleasanter residence than Florence is in spring or autumn.

A city complete in itself, having its own arts and edifices, lively and not too crowded, a capital and not too large, beautiful and gay— such is the first idea of Florence.

Hippolyte Taine, Florence, p. 71.

Other, though not many, cities have histories as noble, treasures as vast; but no other city has them living and ever present in her midst, familiar as household words, and touched by every baby’s hand and peasant’s step, as Florence has.

Every line, every road, every gable, every tower, has some story of the past present in it. Every tocsin that sounds is a chronicle; every bridge that unites the two banks of the river unites also the crowds of the living with the heroism of the dead.

In the winding dusky irregular streets, with the outlines of their loggie and arcades, and the glow of colour that fills their niches and galleries, the “men who have gone before” walk with you; not as elsewhere, mere gliding shades clad in the pallor of a misty memory, but present, as in their daily lives, shading their dreamful eyes against the noonday sun, or setting their brave brows against the mountain wind, laughing and jesting in their manful mirth, and speaking of great gifts to give the world. All this while, though the past is thus close about you, the present is beautiful also, and does not shock you by discord and unseemliness, as it will ever do elsewhere. The throngs that pass you are the same in likeness as those that brushed against Dante or Cavalcanti; the populace that you move amidst is the same bold, vivid, fearless, eager people, with eyes full of dreams, and lips braced close for war, which welcomed Vinci and Cimabue and fought from Monteaperto to Solferino.

And as you go through the streets you will surely see at every step some colour of a fresco on a wall, some quaint curve of a bas-relief on a lintel, some vista of Romanesque arches in a palace court, some dusky interior of a smith’s forge or a wood-seller’s shop, some Renaissance seal-ring glimmering on a trader’s stall, some lovely hues of fruits and herbs tossed down together in a Tre Cento window, some gigantic heap of blossoms being borne aloft on men’s shoulders for a church festivity of roses, something at every step that has some beauty or some charm in it, some graciousness of the ancient time, or some poetry of the present hour.

The beauty of the past goes with you at every step in Florence. Buy eggs in the market, and you buy them where Donatello bought those which fell down in a broken heap before the wonder of the crucifix. Pause in a narrow by-street in a crowd, and it shall be that Borgo Allegri, which the people so baptized for love of the old painter and the new-born art. Stray into a great dark church at evening-time, where peasants tell their beads in the vast marble silence, and you are where the whole city flocked, weeping, at midnight, to look their last upon the dead face of their Michelangelo. Pace up the steps of the palace of the Signoria, and you tread the stone that felt the feet of him to whom so bitterly was known “com’ è duro calle lo scendere e’l salir per l’ altrui scale.” [and how hard a road / The going down and up another’s stairs. Dante Paradiso 17.59–60. Trans. Longfellow.] Buy a knot of March anemones or April arum lilies, and you may bear them with you through the same city ward in which the child Ghirlandajo once played amidst the gold and silver garlands that his father fashioned for the young heads of the Renaissance. Ask for a shoemaker, and you shall find the cobbler sitting with his board in the same old twisting, shadowy street-way where the old man Toscanelli drew his charts that served a fair-haired sailor of Genoa, called Columbus. Toil to fetch a tinker through the squalor of San Nicolò, and there shall fall on you the shadow of the bell-tower, where the old sacristan saved to the world the genius of Night and Day. Glance up to see the hour of the evening, and there, sombre and tragical, will loom above you the walls of the communal palace on which the traitors were painted by the brush of Sarto, and the tower of Giotto, fair and fresh in its perfect grace as though angels had built it in the night just past, “ond’ ella toglie ancora e terza e nona” [From which she taketh still her tierce and nones. Paradiso 15:98. Trans. Longfellow.], as in the noble and simple days before she brake the “cerchia antica” [ancient walls].

Ouida, Pascarèl, vol. 1, pp. 242–245.

Fair Florence, a city so beautiful, that the great Emperor (Charles V.) said that she was fitting to be shown and seen only upon holidays.

James Howell, Familiar Letters, p. 90.

I love Florence; the place looks exquisitely beautiful in its garden ground of vineyards and olive-trees, sung round by the nightingales day and night. If you take one thing with another, there is no place like Florence, I am persuaded, for a place to live in–cheap, tranquil, cheerful, beautiful, within the limits of civilisation, yet out of the crush of it.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Letters, vol.2, pp. 169–70.

O Florence, with thy Tuscan fields and hills,

Thy famous Arno, fed with all the rills,

Thou brightest star of star-bright Italy!

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Garden of Boccaccio, 75–77.

O Foster-nurse of man’s abandoned glory,

Since Athens, its great mother, sunk in splendour,

Thou shadowest forth that mighty shape in story,

As ocean its wrecked fanes, severe yet tender:

The light-invested angel Poesy

Was drawn from the dim world to welcome thee.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mazenghi, 1–6.

What Florence is, the tongue of man or poet may easily fail to describe. The most beautiful of cities, with the golden Arno shot through the breast of her like an arrow, and “non dolet” [painless] all the same.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Letters, vol. 1, p. 343.

Belted with its many bridges, and margined with towers and palaces, Arno is the most beautiful and stately thing in the beautiful and stately city, whether it is in a dramatic passion from the recent rains, or dreamily raving of summer drouth over its dam, and stretching a bar of silver from shore to shore.

W.D. Howells, Tuscan Cities, pp. 138–139.

Oh, that Arno in the sunset, with the moon and evening star standing by, how divine it is!

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Letters, vol. 1, p. 373.

Useful Information

Popular Festivals. — On the Saturday before Easter “Lo Scoppio del Carro” (the waggon-explosion). A car laden with fireworks, in front of the cathedral, is lighted at noon by an artificial dove (Colombina), which descends by a string from the high altar. The success of the dove is watched by thousands, who believe that a good or bad harvest depends upon it. The Befana (the Eve of the Epiphany, January 6) is noisily honoured with torch-processions and singing, the children blowing glass-trumpets. April 1, All Fools’ Day (Pesci d’Aprile). The Giorno dei Grilli (Feast of the Assumption), is an al-fresco festa in the Cascine. Crickets (Grilli) are caught, put in little cages, and sold for luck, and should be fed on lettuce, and let go in the evening. The Festa del Statuto (first Sunday in June) has an illumination and procession in the Cascine. S. Giovanni (June 24) is honoured by fireworks on Ponte alla Carraia, masses and music. The Fair of Impruneta is on October 18.

Sights. — Those who sojourn long at Florence will probably make themselves acquainted with most of the buildings described in these pages. A week is the very least which should be given to Florence. For those who can only spend two days here it may be suggested that they should—

1st day, Morning. — Visit the Piazza della Signoria and the Bargello; the Uffizi (especially the Tribune); and walk through the Galleries to the Pitti, returning by the Ponte Vecchio.

Afternoon. — See the frescoes of the Carmine, and drive by the Colle to S. Miniato; and, if possible, see the lower part of the Boboli Gardens afterwards.

2nd day, Morning. — Or San Michele; Bigallo; the Cathedral and Baptistery; S. Croce; and the Casa di Dante in Via Dante.

Afternoon. See S. Maria Novella, and take the tram to Fiesole: and thereafter the Roman theatre and Etruscan walls, and the Badia; go up to San Francesco to obtain- the views. (Tramway starts from near Giotto’s tower).

Gardens. — Cascine, Boboli.