8.1: Fiesole

THE old city of Fiesole (Faesulae), about three miles distant, is one of the most conspicuous features in all views from Florence, cresting a hollow between the hill-tops to the north-east of the city.

The road to Fiesole is the second of those which turn to the right outside the Porta S. Gallo. The nearest way is that which follows the right bank of the Mugello as far as the Villa Palmieri, formerly Schifanoja (Banish worry) (Dowager-Countess of Crawford and Balcarres), which belonged to the learned Matteo Palmieri, of a family which came from the old castle of Rasojo del Mugello. He was author of the poem “La Città della Vita,” which inspired the great picture of the Assumption by Francesco Botticini,1Both Hare and St. Claire Baddeley give this painting to Botticelli. intended for the Palmieri Chapel in San Pier Maggiore, now in our National Gallery, in which Florence, the Villa Palmieri, with Matteo and his wife are represented. The house was formerly called “La Fonte di Trevisi,” from an old three-faced head of Janus which was placed over it, and only changed its name when it was bought by Matteo Palmieri in 1454 from the Tolomei. It was inhabited by Queen Victoria in 1888.

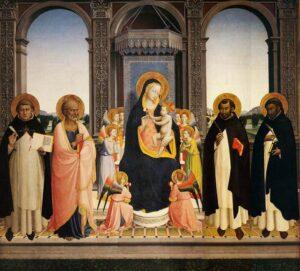

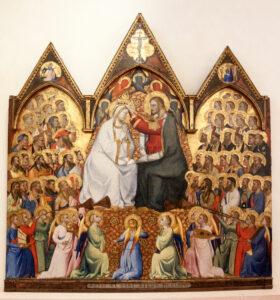

From the villa the road ascends between walls to S. Domenico di Fiesole, half-way up the hillside where the road divides. The convent of this name (right) was united to S. Marco, having been founded in 1406 by the Beato Giovanni di Domenico Bacchini, with the object of restoring the strict observance of cloister rule at a time when it had grown very lax. It was here that Fra Giovanni (called Angelico) and his brother Fra Benedetto lived as monks, and from hence he took his name. The only memorial of him is a picture from his hand in the choir of the church.

The Virgin, enthroned between SS. John the Baptist and John the Evangelist (right), SS. Mary Magdalen and Mark (left), holds the infant Saviour standing on her knee. The four guardian angels stand in pairs behind, grasping their tribute of flowers. The pinnacles are adorned with a crucified Saviour, and the figures of the grieving Virgin and S. John, while in medallions, at the base of the central one, the angel and Virgin annunciate are depicted. In the pediment of this altar-piece, which comprises all the freshness of feeling and religious sentiment peculiar to the master, the scenes from S. Dominic’s life are finely given, and preserve their original beauty.

Crowe and Cavalcaselle, History of Painting in Italy, vol. 1, p. 570.

The choir also contains a Baptism of Christ by Lorenzo di Credi. The famous Coronation of the Virgin by Fra Angelico in the Louvre came from this church.

Here, as a brother of his Order poetically relates, Fra Angelico gathered in abundance the flowers of art which he seemed to have plucked from Paradise, reserving for the pleasant hill of Fiesole the gayest and best-scented that ever issued from his hands. There, in a period of corruption, of pagan doctrine, of infamous policy, of schisms and heresies, he (for eighteen years) shut himself up within a world of his own, which he peopled with heroes and saints, with whom he conversed, prayed, and wept, by turns.

Padre Vincenzo Marchese.

Below the road, on the left, marked by its old campanile, is La Badia di Fiesole, built by Cosimo il Vecchio in 1462. Its terrace has a lovely view. It was in the early church on this site, founded by S. Romolo in A.D. 60, that the Irish missionary saint Donatus, was enthroned as a bishop (c. 860). His head is preserved here in a silver bust. This continued to be the cathedral of Fiesole till the erection of the present building in 1028. The church of La Badia was restored by Andrew, who had accompanied Donatus from Ireland, and remained with him at Fiesole till his death.

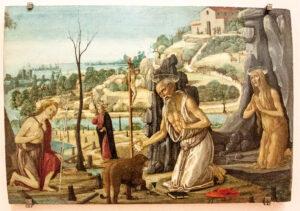

The building of the present Badia is due to Cosimo de’ Medici, 1462. The few and small windows, the round piers, the caps often too small for their columns, the gloomy coldness, all remind one of a romanesque or Norman church. A tablet tells that in 1873 “per crescere l’eleganza della chiesa,” the ancient octagonal chapel was removed, in which its founder, S. Donatus, had rested for 1000 years. The church contains a relief by Desiderio da Settignano, and the refectory a fresco by Giovanni da S. Giovanni, of the angels ministering to Christ in the wilderness.

Giovanni de’ Medici, afterwards Leo X., was invested with his cardinal’s robe in the monastery, which was long the residence of the Cavaliere Francesco Inghirami, the patriarch of Etruscan antiquarians.

A little to the right of S. Domenico, embosomed in cypresses, is the Villa Landore (once Gherardesca), where Walter Savage Landor passed many years of his unhappy married life. It is in the parish of Majano, of which a history has been written by the late Mr. Temple Leader (owner of a beautiful villa there), and which is the native place of many distinguished men, amongst the best known of whom are the sculptors and architects Benedetto and Giuliano da Majano and the XIV. c. poet, Dante da Majano.

I stuck to my Boccaccio haunts, as to an old home, . . . My almost daily walk was to Fiesole, through a path skirted with wild myrtle and cyclamen; and I stopped at the cloister of the Doccia, and sate on the pretty melancholy platform behind it, reading, or looking through the pines down to Florence.

Leigh Hunt, Autobiography, vol. 3, pp. 106–07.

On either side of Majano were laid the two scenes of the “Decameron” of Boccaccio; the little streams that embrace it, the Affrico and the Mensola, were the metamorphosed lovers in his Nimphale Fiesolano; within view was the Villa Gherardi, before the village the hills of Fiesole, and at its feet the Valley of the Ladies. Every spot around was an illustrious memory. To the left, the house of Macchiavelli, still further in that direction, nestling amid the blue hills, the white village of Settignano, where Michelangelo was born; on the banks of the neighbouring Mugnone, the house of Dante; and in the background, Galileo’s villa of Arcetri and the palaces and cathedral of Florence. In the centre of this noble landscape, forming part of the village of S. Domenico di Fiesole, is Landor’s villa. The Valley of the Ladies was in his grounds; the Affrico and Mensola ran through them; above was the ivy-clad convent of the Doccia overhung with cyress; and from his entrance-gate might be seen Valdarno and Vallombrosa.

John Forster, Walter Savage Landor, vol. 2, pp. 223–24.

Landor himself wrote of his Florentine homes: —

From France to Italy my steps I bent,

And pitcht at Arno’s side my household tent.

Six years the Medicean Palace held

My wandering Lares; then they went afield,

Where the hewn rocks of Fiesole impend

O’er Doccia’s dell, and fig and olive blend.

There the twin streams in Affrico unite,

One dimly seen, the other out of sight,

But ever playing in his smoothen’d bed

Of polisht stone, and willing to be led

Where clustering vines protect him from the sun,

Never too grave to smile, too tired to run,

Here, by the lake, Boccaccio’s fair brigade

Beguiled the hours, and tale for tale repaid.

How happy! Oh, how happy had I been

With friends and children in this quiet scene!

Its quiet was not destined to be mine;

‘Twas hard to keep, ‘twas harder to resign.

Walter Savage Landor. (Quoted in Forster, Walter Savage Landor, vol. 2, p. 199.)

Visions of the fair Fiammetta and her companions arise as one remembers how on the sixth day after Elisa had crowned Diomed king, and laughingly told him it was time he should find out what a charge it was to rule over and guide women, the three youths sat down to play at draughts, while she led the ladies to an unknown valley. Little or no sun entered there, even when high in the heavens it only just touched the earth clothed with sward of finest grass, and rich in purple and other flowers. Beside this a rivulet, which was not a less delight, came from a valley dividing two of those small hills. When the ladies had observed everything they commended the place exceedingly, and the heat being great they decided to bathe, and all seven disrobed and went down one by one to the lovely water, which hid their white bodies no more than a thin glass would hide a crimson rose.

Janet Ross, Florentine Villas, pp. 113–14.

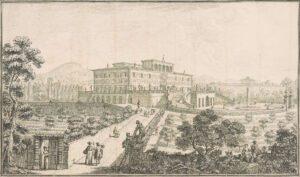

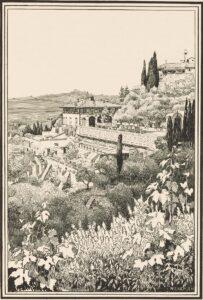

A steep footway ascends, by the chapel of S. Ansano, to the gates of Il Palagio or the Villa Medici,2This was one of the four country residences of Cosimo; the others were Carreggi, Cafaggiolo, and Trebbia. The lane which passes Villa Landore leads to the Villa Fontanelle, which belongs to the old family of the Turchi, with one of whom S. Luigi Gonzaga was left as a pupil in his boyhood by his father, who was a friend of the Medici. The little chapel of the villa is open on the festa of the saint. On the hill above the Villa Fiaschi was the convent of Doccia, built in the XV. c. The portico was by Santi di Tito, from designs of Michelangelo. a beautiful old palace with balustraded terraces and gardens of ancient cypresses, built by Michelozzo for Giovanni de’ Medici, and the favourite residence of Lorenzo, the Magnificent.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Villa Medici (detail Assumption of the Virgin, Tornabuoni Chapel, S. Maria Novella), 1486-90

In a villa overhanging the towers of Florence, on the steep slope of that lofty hill crowned by the mother city, the ancient Fiesole, in gardens which Tully might have envied, with Ficino, Landino, and Politian at his side, Lorenzo delighted his hours of leisure with the beautiful visions of Platonic philosophy, for which the summer stillness of an Italian sky appears the most congenial accompaniment.

Never could the sympathies of the soul with outward nature be more finely touched; never could more striking suggestions be presented to the philosopher and the statesman. Florence lay beneath them; not with all the magnificence that the latter Medici have given her, but, thanks to the piety of former times, presenting almost as varied an outline to the sky. One man, the wonder of Cosimo’s age, Brunelleschi, had crowned the beautiful city with the vast dome of its cathedral; a structure unthought of in Italy before, and rarely since surpassed. It seemed, amidst clustering towers of inferior churches, an emblem of the Catholic hierarchy under its supreme head; like Rome itself, imposing, unbroken, unchangeable, radiating in equal expansion to every part of the earth, and directing its convergent curves to heaven. Round this were numbered, at unequal heights, the Baptistery, with its gates, as Michelangelo styled them, worthy of Paradise; the tall and richly decorated belfry of Giotto; the church of the Carmine, with the frescoes of Masaccio; those of Santa Maria Novella (in the language of the same great man), beautiful as a bride; of Santa Croce, second only in magnificence to the cathedral; of S. Marco, and of S. Spirito, another great monument of the genius of Brunelleschi; the numerous convents that rose within the walls of Florence, or were scattered immediately about them. From these the eye might turn to the trophies of a republican government that was rapidly giving way before the citizen-prince who now surveyed them; the Palazzo Vecchio, in which the signory of Florence held their councils, raised by the Guelf aristocracy, the exclusive, but not tyrannous faction that long swayed the city; or the new and unfinished palace which Brunelleschi had designed for one of the Pitti family before they fell, as others had already done, in the fruitless struggle against the House of Medici, itself destined to become the abode of the victorious race, and to perpetuate, by retaining its name, the revolution that had raised them to power.

Harry Hallam, Literature of Europe (1860), vol. 1, p. 243.

The place is well described by the verses of Politian:

Such was my song, with idle thought

In Fiesole’s cool grottoes wrought,

Where from the Medici’s retreat

On that famed mount, beneath my feet

The Tuscan citv I survey,

And Arno winding far away.

Here sometime at happy leisure

Bounteous Lorenzo takes his pleasure

His friends to entertain and feast.

(Of Phoebus’ sons himself not least)

Offering a haven safe and free

To storm tossed ships of Poesy.

Poliziano, Rusticus. Trans. R. C. Trevelyan.

See Janet Ross, Florentine Villas, p. 86.

Here lived the eccentric Lady Orford in 1782. At her death the villa passed to Cavaliere Mozzi, whom Horace Mann described as her “old Cicisbeo [lover],” who in turn sold it to the Buoninsegni from whom the Englishman William Blundell Spence bought the property in 1862. In the chapel is the very beautiful tomb, by Fantacchiotti, of Mrs. Spence. In 1911 Lady Sybil Cutting purchased the property from the Macalmont family. Lady Sybil’s daughter, who spent her early years here, was the author and biographer Iris Origo.

From the little platform outside the villa gates the view is exquisitely beautiful—of Florence and the rich plain of the Arno, with the villa-dotted hills and the surrounding chain of amethystine mountains. Perhaps spring, when the purple cloud-shadows are travelling over the delicate green of the young cornfields, and when tulips and anemones make every bank blaze with colour, is the most beautiful season.

Chi Fiesol hedificò conobbe el loco

Come gia per gli cieli ben composto.

Whoever built Fiesole knew the place

As it was for the well ordersed skies.

Fazio degli Uberti, Il Dittamondo, p. 225.

A few steps now bring us into the wide Piazza Mino da Fiesole, the ancient Faesulae, and it is strange, within sight of Florence and her great cathedral, to find this ancient village-bishopric with a cathedral and the 14th-century Palazzo Pretorio, currently the town hall. Its loggie display the stemme (coat of arms) of former podestà. In front of the Palazzo, Oreste Calzolari’s Equestrian statue, 1906, commemorates the meeting between King Vittorio Emanuele II and Giuseppe Garibaldi at Teano in 1860 that led to a united Italy.

It was hither that Catiline fled from Rome after his conspiracy, and the fancy of its historian, Malaspina, has made a romance for Fiesole founded on the story of “Catellino,” who wages war against Fiorino, King of Rome. The latter is killed in battle, and the new city, Fiorenza Magna, is founded in his memory. Afterwards the new city finds a friend in Attila, who destroys Florence and rebuilds Fiesole. Dante alludes to Fiesole as if it were the cradle of Florence: —

Ma quell’ ingrato popolo maligno,

Che discese di Fiesole ab antico,

E tiene ancor del monte e del macigno

But that ungrateful and malignant people,

Which of old time from Fesole descended,

And smacks still of the mountain and the granite.

Dante Inferno 15:61–63. Trans. Longfellow.

The name of Faesulae constantly occurs in history. It is mentioned by Polybius, Sallust, and Procopius, but never as playing any leading part. Always a city, it never became great; as Mr. Freeman says, it has been almost as eternal in its littleness as Rome in her greatness.

Milton and Galileo give a glory to Fiesole beyond even its starry antiquity: nor perhaps is there a name eminent in the best annals of Florence to which some connections cannot be traced with this favoured spot. When it was full of wood, it must have been eminently beautiful. It is at present indeed full of vines and olives, but this is not wood, woody.

Leigh Hunt, The Wishing-Cap Papers, p. 99.

Duomo di S. Romolo, 1028 with later additions (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Duomo (1028), with its slender crenellated tower, occupies one side of the piazza. It is dedicated to S. Romolo, first bishop and apostle of Fiesole, who is said to have been a convert of S. Peter, and to have received a special mission from him to preach at Faesulae. His image, by one of the Della Robbia, is seen in a niche above the west doorway. Under Nero he was imprisoned and martyred. The church was begun in 1028, but little remains of so early a date. It is in form a basilica, having narrow aisles of ten arcaded bays, and a choir with cross-arms raised high, and carried on five arches above a crypt. It has a clear-storey of small round lights, only in S. aisle. Beneath the high altar rests the Irish bishop S. Donatus, whose remains were brought here from the Badia. Over the altar is a triptych of Madonna and saints, and the vault of the apse contains frescoes in eleven sections.

In the chapel R. of the high-altar is the tomb of Bishop Leonardo Salutati, a member of one of the noblest Florentine families,3The ornaments of Benedetto Salutati and his horse, when they appeared in a tournament in Piazza S. Croce, were valued at 5000 gold florins. the learned friend of Pope Eugenius IV., executed in 1462 by Mino di Giovanni or da Fiesole, who, however, was not born here.

Mino da Fiesole, Bishop Salutati, 1466 (photo via Researchgate)

The bust of Bishop Salutati is certainly one of the most living and strongly characterised “counterfeit presentments” of nature ever produced in marble. Any one who has looked at those piercing eyes, strongly marked features, and that mouth, with its combined bitterness and sweetness of expression, knows that the bishop was a man of nervous temperament, a dry logical reasoner, who, though sometimes sharp in his words, was always kindly in his deeds. From the top of his jewelled mitre to the rich robe upon his shoulders, this bust is finished like a gem. It stands below a sarcophagus, resting upon ornate consoles, upon an architrave supported by pilasters and adorned with arabesques. In design the tomb is perfectly novel, and, as far as we know, has never been repeated, despite its beauty and fitness. Directly opposite is the lovely altar-piece which Mino sculptured by Salutati’s order and at his expense. It is divided into three compartments, containing a central group of the kneeling Madonna with the Infant Christ and S. John, on either side of which are statuettes of San Lorenzo and San Remigius, under an entablature on which is placed a poor bust of Our Lord. The Infant Saviour, sitting upon the steps at the Madonna’s feet, holds a globe upon his knee, and smilingly stretches out his left hand to the little S. John, who kneels before him in artless simplicity. Upon these children, whose grace and unconsciousness remind us of those of Raffaelle, the kneeling Virgin looks down with a gentle smile, her hands crossed upon her breast.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, pp. 208–09.

One of the ancient ambones of the cathedral, taken away in 1544, was first preserved in S. Pietro Scheraggio, and is now in S. Leonardo in Arcetri. On N. side is a little cloister with a granite column in the centre.

S. Maria Primerana, a little church in the piazza, contains a tabernacle by one of the Robbias, and a picture by Andrea da Fiesole. A column in front of the church commemorates the return to Tuscany of Ferdinand III. in 1799.

The little XVII. c. oratory of Fonte Lucente contains a crucifix reputed miraculous.

The most important remains of the Etruscan fortifications are on the northern brow of the hill, where they rise to a height of from twenty to thirty feet.

It is pleasant indeed to sit here, under a line of dark cypresses that are firmly rooted in the crevices of the mighty wall of the Etruscan town. The modern town is just a hundred yards away, slightly on the higher ground. The slender campanile stands relieved against the pale blue sky; while olives with silver-green, and the more brilliant rising wheat beneath them, fill the foreground. Birds are chirruping among the cypresses, and large droves of labouring milk-white clouds pass over, shading the landscape a good deal, though the grass shines brilliantly wherever the sun-beams fall. Behind us spreads an arid brown-grey basin of mountains, in reality much cultivated, but things are not far forward; and the mountains themselves are bare of trees, saving where at rare intervals a townlet with its grove of cypresses appears. White farms and “villini” are sprinkled everywhere, invisible from Florence.

Unattributed.

Behind the cathedral, in a garden, are some remains of the Roman Theatre, which once accommodated 3,000 spectators, and baths. There is now much to see, and it is a charming spot half-buried in flowers.4An Etruscan altar, with base-moulding similar to that of the pedestals under the Niger Lapis at Rome, is seen N. of theatre. In the summer concerts and plays are performed here. Some of the outer wall and some of the seats are visible. Some vaults beneath, of opus incertum, are called by the Fiesolani “Le Buche delle Fate” or Dens of the Fairies.

Museo Civico, 1914 (photo corvinus)

The façade of the Museo Civico (1914) resembles a Roman temple with a pediment surmounting an entablature that is supported by two Ionic columns in anta and pilasters of the same order on the sides. contains Etruscan, Roman, and Lombard archaeological objects.5 The museum opened in 1878 on the ground floor of Palazzo Pretorio and moved into the present building in 1914. In 1985 Alfiero Costantini donated a superb collection of Greek vases, which are displayed on the upper floor. Especially note an alabaster Tessera Gladiatoria allowing Euporus a free entry to public spectacles, B.C. 76. Tickets must be obtained at the entrance to the theatre, away on the left.

Sant’Alessandro (R). Convent of S. Francesco at rear (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

In the Borgo Unto is a curious fountain in a subterranean passage approached by a gothic archway. It is called Fonte Sotterra, and its pure waters supply the whole neighbourhood. A stony path, opposite the west end of the cathedral, leads up to what was no doubt the Arx of the ancient city. Here are a Franciscan Convent and the Church of S. Alessandro, with eighteen cipollino columns, said to have belonged to a temple of Bacchus. The view is glorious.

A veder pien di tante ville i colli,

Par che ‘l terren ve le gergmogli, come

Vermene gemogliar suole e rampolli.

Se dentro un mur, sott’ un medesmo nome

Fosser raccolti i tuoi palazzi sparsi,

Non ti sarian da pareggiar due Rome.

To see the hills so full of many villas

It seems the soil there sprouts like

Shoots on budding branches.

Were your scattered palaces collected

Under one name within a city wall

Two Romes won’t equal you.

Ludovico Ariosto, Poems (Rime), cap. xvi, p. 299.

If we now ascend the Via di S. Francesco and gain the first terrace, where the women are selling straw fans, we shall find a magnificent prospect. The Arno runs out west in a long silvery line, and the mountain ridges are bedimmed with a golden haze. The setting sun pours a soft rosy blaze along the western flank of Florence, and the dim red dome itself is a great diadem. To the left of it S. Miniato throws back the light from its facade, and behind it rises the hill where Gelsomino is, which looks into Val d’Ema. We are N.E. of it all, and below us immediately the villas sit deep amid their olives and vines, guarded by lines of cypresses, like Angelico’s angels, “up to their knees in flowers.” Above, we reach a little piazza, sweet with clover and bees, which overlooks the cathedral and theatre, and across to a further height. By ringing the bell we can enter the convent and pass along its cloisters to obtain exquisite views, or go into the vineyard and bosco beyond and listen to the nightingales, and recollect S. Francis and his love of birds.

At the top of the hill, the church of San Francesco, dating from approximately 1330, occupies the site of the former Etruscan acropolis. Between 1905-07 Giuseppe Castellucci remodeled the church in a neo-Gothic style adding a rose window and cusped Gothic arch canopy. The severe single-aisled nave has a pointed barrel vault. The Corinthian chancel arch in pietra serena is attributed to Benedetto da Maiano (1442–97).

San Bernardino of Siena (1380–1444) was superior of the convent for several years after 1417. His cell can be visited if one climbs the stairs to the convent’s first floor.

Few travellers can forget the peculiar landscape of this district of the Apennine, as they ascend the hill which rises from Florence. They pass continually beneath the walls of villas bright in perfect luxury, and beside cypress hedges, enclosing fair terraced gardens, where the masses of oleander and magnolia, motionless as leaves in a picture, inlay alternately upon the blue sky their branching lightness of pale rose-colour and deep green breadth of shade, studded with balls of budding silver, and showing at intervals through their framework of rich leaf and rubied flower the far-away bends of the Arno beneath its slopes of olive, and the purple peaks of the Carrara mountains, tossing themselves against the western distance, where the streaks of motionless cloud burn above the Pisan sea. The traveller passes the Fiesolian ridge, and all is changed. The country is on a sudden lonely. Here and there, indeed, are seen the scattered houses of a farm grouped gracefully upon the hillside—here and there a fragment of tower upon a distant rock; but neither gardens, nor flowers, nor glittering palace walls, only a grey extent of mountain ground tufted irregularly with ilex and olive; a scene not sublime, for its forms are subdued and low; not desolate, for its valleys are full of sown fields and tended pastures; not rich nor lovely, but sunburnt and sorrowful; becoming wilder every instant as the road winds into its recesses, ascending still, until the higher woods, now partly oak and partly pine, drooping back from the central nest of the Apennine, leave a pastoral wilderness of scattered rock and arid grass, withered away here by frost, and there by lambent tongues of earth-fed fire. Giotto passed the first ten years of his life, a shepherd-boy, among these hills; was found by Cimabue, near his native village,6At Vespignano, a village near Borgo S. Lorenzo, where Giotto was the son of a poor contadino called Bondone. drawing one of his sheep upon a smooth stone; was yielded up by his father, “a simple person, a labourer of the earth,” to the guardianship of the painter, who, by his own work, had already made the streets of Florence ring with joy; attended him to Florence, and became his disciple.

John Ruskin, Giotto and His Works in Padua, pp. 11–12.

Of the many villas near Fiesole, the Villa Allegri, chiefly of the XVII. c., dates from the XV. c., and has passed through many illustrious hands. In the chapel are many monuments of the Allegri family.

Vincigliata (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

In the hills beyond Fiesole is the late Mr. J. Temple Leader’s7John Temple Leader (1810-1903), an English politician who moved to France in 1844, and subsequently to Florence where he died. beautiful castle-villa of Vincigliata, built in the latter part of the XIX. c. on the ruins of a castle of the Visdomini, and containing collections of ancient furniture, armour, &c. One of the rooms is decorated with frescoes from the ancient Hospital of S. Maria della Scala. A courtyard has frescoes relating to the story of the castle, especially its destruction by Sir John Hawkwood in 1364. The tower of the church bears the arms of the Alessandri, and it contains a beautiful XV. c. lavabo and ciborio. The hill above is crowned by Castel di Poggio, the ancient fortress of the Del Manzecca family, afterwards of the Alessandri (who restored it in the XV. c.), of the Girolami and Buonacorsi. The great villa of Il Querceto, in this direction, is of the XVII. c., but occupies the site of an old castle of the Strozzi. In its chapel is a tabernacle by Luca della Robbia. It is a beautiful drive back to Florence from Fiesole by Vincigliata and Ponte a Mensola.

Camerata, on the lower slopes of the Fiesolan hills, has a beautiful view of Florence. Amongst its many country-houses, the Villa Rasponi belonged to the Gaddi family, of which the painters Taddeo and Agnolo were members. At La Querce, the Collegia dei Barnabiti occupies the site of a villa of the Grand-Duke Leopoldo. The Villa Altrocchi, formerly La Topaia, belonged to the Antinori from 1567. The Villa Aurora belonged to the Falconieri.