The Piazza S. Croce. In 1250 the first popular Assembly was held here; and here, in 1342, Walter de Brienne, Duke of Athens, coming out of S. Croce, first roused the populace against the nobles. The statue of Dante, by Enrico Pazzi, was placed in the centre of the piazza on the sixth centenary of his birth, 1864, in presence of Victor Emmanuel and deputations from all parts of Italy, hungering for that independence and unity “promised by our ever-living poet.” After the flood of 1966, the statue was moved to its present location on the north side of the basilica.

Tender Dante loved his Florence well,

While Florence now to love him is content.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Casa Guidi Windows, Part 1:15.

Palazzo Stufa, 14th c. (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

On the left, or S. side of the Piazza, are several picturesque palaces, with first floors corbelled out on the characteristic brackets (sporti), and remains of frescoes upon the wall. No. 23, Palazzo Stufa, once Antella, was built by Giulio Parigi. The Antellesi bore: Argent, a chevron gules, traces of the shield can be seen among the frescoes by Giovanni da San Giovanni, supported by children. There is a white marble disc beneath the third window (coming from the church) set to mark the frontier line across the Piazza between the rival players in the Giuoco del Calcio, which was played here time out of mind; even (out of bravado) during the siege of 1529. No. 1 was built for the Cocchi by Baccio D’Agnolo (1462–1543), and passed to the Serristori.1Arms of Serristori: a fess between three stars, two and one. No. 8 was once the Florentine residence of the Barberini, to whom Milton was indebted while in Rome. The family of Maffeo Barberini, the future Pope Urban VIII., occupied this palazzo when in Florence. The houses on the farther side, including Palazzo Serristori, stand upon the line of the second circuit of walls, leading by a street (S.) direct to Ponte alle Grazie, and along which stood the towers and palaces of the Alberti, a noble family who belonged to the Calimala Guild and were intimate partisans of Cosimo de’ Medici, and from whom sprang the immortal Leon Battista Alberti.2Arms of Alberti: azure, a cross chain with central ring, argent. Into the Piazza falls at S.W. angle the Borgo dei Greci, the quarter of the Peruzzi family, probably named from Greek merchants in their service or that of the Acciajuoli, when Dukes of Corinth. Next it falls in Via Anguillara, an equally interesting street, and leading like it direct to the Piazza Signoria. Some of the houses have hatched ornament—allo sgraffiato.

Santa Croce façade, before 1863 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Nicolo Matas, Santa Croce façade, 1863 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

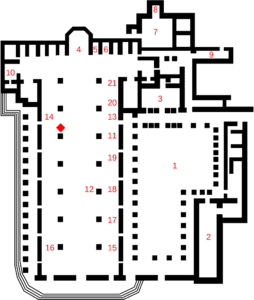

Santa Croce Plan (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Plan of the Basilica of Santa Croce: 1) First Cloister 2) Refectory 3) Pazzi Chapel 4) Choir 5) Bardi Chapel 6) Peruzzi Chapel 7) Sacristy 8) Rinuccini Chapel 9) Chapel of the Noviciate 10) Bardi di Vernio Chapel 11) Donatello”Annunciation” 12) Pulpit, by Benedetto da Maiano 13) Bernardo Rossellino “Tomb of Leonardo Bruni” 14) Desiderio da Settignano “Tomb of Carlo Marsuppini” 15) Tomb of Michelangelo Buonarroti 16) Tomb of Galileo Galilei 17) Cenotaph of Dante Alighieri 18) Tomb of Vittorio Alfieri 19) Tomb of Niccolò Machiavelli 20) Cenotaph of Gioacchino Rossini 21) Tomb of Ugo Foscolo.

The Church of Santa Croce was begun in 1297, by Franciscan monks, from the designs of Arnolfo di Lapo, on ground given them by the Altafronte family. But little remains of the original building externally; the modern façade, in the mediaeval diagonal style, of black and white marble, a work of Nicolo Matas, is due to the generosity of an Englishman, Mr. Francis Sloane, and was finished in 1863. In the north porch are some mediaeval sarcophagi. The Holy Cross is several times represented.

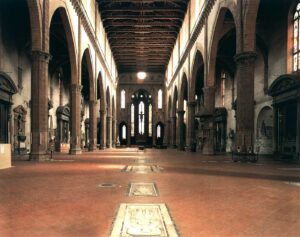

The somewhat tatterdemalion interior is striking from its vast width, and the blaze of rainbow glass around the choir gives some compensating richness of colour, but it is spoilt by the brown and white wash with which it is covered, and by its fine, but unbefitting, roof. It is a peculiarity of the nave that it has no side chapels. The chancel is almost entirely of the time of Arnolfo di Lapo. The patchy colour given to it by the numerous grey slabs, tombs, canopies, renaissance altars, blocked-up aisle-windows, and frescoed walls is, after all, becoming to an ancient and ill-kept abbey-church.

In 1514 S. Croce became celebrated for the extraordinary religious revival under Fra Francesco da Montepulciano, who preached sermons so awful that his vast audience would sometimes cry “Misericordia!” with one voice, at other times almost seemed as if they had lost their senses with horror and grief.

The nave extends seven bays in length, and is followed above the arches by a corbelled gallery or passage, above which occurs the clear-storey, every alternate window being closed up. The columns are of serena and octagonal in form, and upon several are fastened painted and carven plaques, bearing old Florentine coats-of-arms. In the olden days the bare aisles were rich with votive pennons, swords, and helmets of those who had fought or fallen. It is to be feared that Vasari swept much of this attraction before him, when Duke Cosimo I. gave him orders to improve the church in 1560. He is the author of the ugly altars we now see in the aisles, and he moved the choir, as was done at S. Maria Novella, from the middle of the church, together with the pulpitum and rood. The aisle-windows (S.), filled with precious fourteenth-century glass with rich quarry borders, are a blaze of glory on bright May afternoons above the gloomy array of often very ugly tombs. The roof, though unbefitting, forms an interesting study of gabled timber work. It, moreover, interferes with the effect of the church by truncating the pediment at either end. The transepts form here the head of the letter T.

The nave is cut across sharply by a line of ten chapels, the apse being only a tall recess in the midst of them.

John Ruskin, Mornings in Florence, p. 12.

It is perhaps more than that, for the choir is pentagonal, covered with frescoes, and lit with three lofty windows of twelve panels a-piece of superb glowing fourteenth-century glass, and the effect is greatly increased by there being another tall window over the first chapel arch on either side the choir, filled with Apostles, Kings, and Popes. The arms of the Bardi—or, a bend, lozengy gules—frequently occurs.

Over the West door (from within) is a statue of S. Louis of Toulouse, elder brother of King Robert the Wise of Naples, by Donatello; not a very impressive work of its great sculptor who, being chaffed about it, is said to have retorted that it was quite good enough for a man who had been so foolish as to exchange his kingdom for a monastery. If, however, we reflect what kind of a pleasure it may have been to wear a Neapolitan, or any other, crown in the 14thcentury, we may not a little question the unwisdom of S. Louis!

The magnificent circular window above it is from a design of Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455), and represents the Deposition. Below it is placed a circular stone medallion, bearing the sacred monogram and inscription, “In nomine Jesu omne genu flectatur cœlestium, terrestrium, et inferorum.” [At the name of Jesus every knee should bend, of things in heaven, on earth, and beneath.3Philippians 2:10. It was placed by S. Bernardino of Siena (1437) upon the façade of the Church.

The Church of S. Croce would disappoint you as much inside as out, if the presence of great men did not always cast a mingled shadow of the awful and beautiful over our thoughts.

Leigh Hunt, Autobiography, vol. 3, p. 102.

The Church is almost surrounded by monuments of the great men of Italy, though comparatively few of them possess artistic interest.

See these huge tombs on your right hand and left, with their alternate gable and round tops, and the paltriest of all possible sculpture, trying to be grand by bigness, and pathetic by expense.

John Ruskin, Mornings in Florence, p. 14.

In Santa Croce’s holy precincts lie

Ashes which make it holier, dust which is

Even in itself an immortality,

Though there were nothing save the past, and this,

The particle of those sublimities

Which have relapsed to chaos:—here repose

Angelo’s, Alfieri’s bones, and his,

The starry Galileo, with his woes;

Here Machiavelli’s earth, return’d to whence it rose.

Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, 4:54.

Giorgio Vasari, Tomb of Michelangelo, 1570 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Giovanni Battista Foggini, Tomb of Galileo, 1722–27 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Innocento Spinazzi, Tomb of Machiavelli, 1787 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

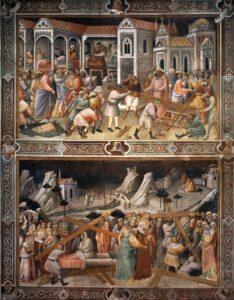

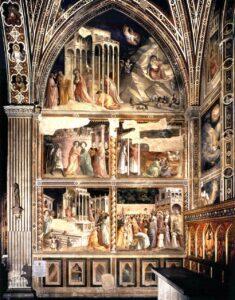

There is probably no stronger testimony existing in the world of the profound religious force exerted by S. Francis over men’s minds and hearts than that so many men of varied rank and genius should have desired to lie in his sanctuary; force exerted, too, and sustained through these especial centuries when the long suppressed intellectual ambitions of mankind had forced their way to the light. But before we refer to their tombs in detail, let us pass up the middle of the Church, merely noticing that several slabs with much worn-down effigies of bishops and clerics, attest the locality of the original presbyterium, a favourite and particularly sought-for resting-place, and so gain the crossing of the transept. We may then pass into the modern monk’s choir behind the high altar, and admire the frescoes illustrating the whole legend of the Cross and its re-discovery by S. Helena. It commences at the top of the South wall, and the whole series on both walls are the work of Agnolo Gaddi, son of Taddeo (d. 1396), who painted them at the cost of Jacopo degli Alberti.

1. Seth receives from an Angel a chosen branch, which he plants in the breast of Adam.

2. The Queen of Sheba adores the tree, and Solomon commands it to be buried.

3. Taken from the pool of Bethesda, it is formed into a cross.

4. Its discovery by the Empress Helena, and the recovery of a sick woman.

On the North wall—

- People venerating the Cross while being carried in procession.

- The capture of the Cross by Chosroes, King of Persia, at his taking of Jerusalem.

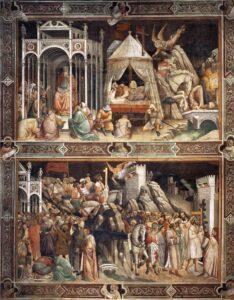

- The Vision of Chosroes. The King seated in his golden tower, and posing as the King of Kings. The defeat of his son by the Emperor Heraclius.

- Heraclius carries the Cross back to Jerusalem. He occurs twice in the fresco, on horseback and on foot, having presumed to enter the Holy City on his charger, until, warned by an angel, he dismounted, and bore the Cross into the city without hindrance. Agnolo Gaddi himself is portrayed in the right-hand corner, bearded and wearing a red hood.

The beautiful glass is of the 14th century, c. 1325.

Let us now take the successive chapels on the S. of the Choir.

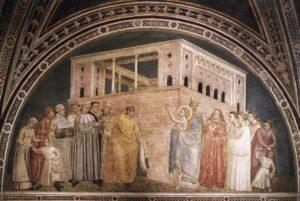

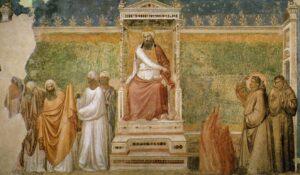

(1). The Bardi (chapel), whose arms (or, a bend lozengy gules) appears in the windows here and there, owned this chapel, and were one of the leading banking firms in fourteenth-century Florence—the Villani, and Boccaccio’s father, being in their service. For them Giotto has illustrated his own favourite subject, the life of S. Francis.

Beginning on the North Wall—

On the South Wall—

Left of the window, S. Louis of Toulouse and Sta. Chiara. On the right, his great uncle, Louis IX. of France, and S. Elizabeth of Hungary. On the vault are presented S. Francis in glory, with the three virtues of his rule—Obedience, Chastity, and, over the arch, Poverty.

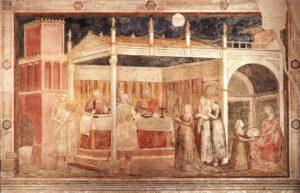

(2) The next chapel, equally famous for its paintings, which were restored in 1844, is that of the Peruzzi, two of whom are here commemorated by monuments. The frescoes, also by Giotto, and his most representative works, illustrate the lives of the two SS. John.

On the North Wall—

On South Wall—

These are much less restored than are the paintings in the Bardi Chapel. They tell their story with an almost Homeric force and simplicity, unembarrassed by learned accessories.

(3) The third chapel, formerly Giugni, and now Bonaparte, once likewise decorated by Giotto, has lost every trace of his work. It belonged to the ex-King of Spain, Joseph Bonaparte, hence his monument, and that of Giulia Clary, his wife, by Pampaloni. That of their daughter Charlotte, wife of Charles L. Napoleon, brother of the Emperor Napoleon III. (1839), is by Bartolini. A slab placed on the pilaster between the two last chapels commemorates the Emperor.

(4) The fourth, or Soderini-Riccardi Chapel, contains the Discovery of the Cross, by Jean Bilivert (1576–1644); S. Francis praying, by Matteo Rosselli; and S. Francis giving his goods to the Poor, by Passignano (1566–1638). The vault is painted with episodes in the life of S. Andrew by Giov. de San Giovanni. Observe the beautiful late thirteenth-century glass in these chapels.

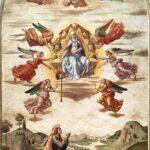

(5) The fifth, or Morelli-Velluti, is dedicated to S. Michele, and decorated by a series of much-damaged Giottesque frescoes illustrating the story of the appearance of S. Michael to a rich shepherd on Monte Gargano, which caused that mountain promontory to become the great Apulian place of pilgrimage in the Middle Ages, to which even Canute of England found his way. The altar-piece, Assumption of the Virgin, is by C. Allori. The Velluti were important merchants, and are commemorated in the names of one or more streets.

The door in the S. Transept leads to the Sacristy, which we now enter through a door on the left. It is a square chamber, containing also the railed-off Rinuccini chapel. On application, the fine inlaid presses will be shown, together with ancient vestments, some of beauty, missals, &c., which form a museum. A number of little Giottesque paintings, which formerly adorned the panelling of the walls, were removed to the Accademia. On the S. wall are frescoes of the same school. The two crucifixes here are attributed, one to Margheritone, and the other to Giotto. There is another, by Santi di Tito; a Nativity, by Bugiardini, a scholar of Domenico Ghirlandaio; and a S. Antonio, attributed to Perugino; and near the door is a Head of Christ, by A. Della Robbia.

The walls of the Rinuccini Chapel are decorated with ill-preserved frescoes by Giovanni da Milano, the most important of Taddeo Gaddi’s pupils. On the vaulting is the Saviour in the act of Benediction, and four prophets.

The Altar-piece and the Frescoes belong to the last quarter of the fourteenth century, and the latter depict the lives of the Virgin and Mary Magdalene, both facts and legends.

Michelozzo, Medici Chapel, 1435-45 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

We now turn to the left along the corridor, and enter the Chapel of the Medici, dedicated to their patron saints, Cosmo and Damiano, physician-martyrs, and containing some of the most beautiful objects in the church. Let us first, however, before looking at these, call to mind that the body of Galileo (1542) rested here for fifteen years before it was permitted to be interred befittingly in the nave of the church itself. Vincenzo Viviani, his disciple (1703), was likewise brought in here. The chapel was built for Cosimo by Michelozzo.

Andrea and Giovanni della Robbia, Medici Chapel Altarpiece, c. 1495 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Above the altar is a Della Robbia Relief, showing the Virgin and Child beneath a frieze of charming cherubim, with angels crowning her, between S. John the Baptist, S. Elizabeth, with roses falling, S. Anthony of Padua; and (L. H.) S. Lawrence, S. Francis, and S. Louis of Toulouse. Above the door is a lunette, probably by Andrea della Robbia, representing Christ between angels, with a fruit-garland around. There is a fascinating Ciborio by Mino da Fiesole (1431–84).

A Coronation of the Virgin, in five panels, formerly the altar-piece of the Baroncelli Chapel, is a beautiful work, with forged signature of Giotto, whose painting it, nevertheless, probably is.

To perfect decorum and repose Giotto added in this altar-piece his well-known quality of simplicity in drapery.

Crowe and Cavalcaselle, New History of Painting in Italy, vol. 1, p. 309.

The predella contains SS. Francis, the Baptist, Peter, and Paul the Hermit.

Baroncelli Chapel, 14th century window

On returning to the church, on our left is the Cappella Baroncelli, with a grand fourteenth-century window of eight panels, with arms of the Baroncelli in the crowning light, below which S. Francis is seen receiving the stigmata from a winged crucified Saviour.4Arms of Baroncelli: 6 bands, silver, gules. Below are SS. Peter and John Baptist, SS. Augustine and Gregory, and SS. John and Bartholomew—all set in crocketted canopies, enclosed in a gorgeous bordure of vine-leaves, green and gold, on a blue and red ground. The colossal dead Christ before it, upon the altar, is by Bandinelli.

The cross-vaulting contains four angels. At the sides next the window, in six compartments, are frescoes of Taddeo Gaddi.

Taddeo Gaddi, L. H. side of window:

The Annunciation,

The Angels appearing to the Shepherds,

The Adoration of the Shepherds.

Taddeo Gaddi, Baroncelli Chapel, South Wall, c. 1330 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Taddeo Gaddi, R.H. side of window:

The Visitation,

Bethlehem,

The Magi; while in the adjoining pilaster are David and S. Giuseppe.

On the L. wall of the chapel (E.), in five compartments, are:

(photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Taddeo Gaddi: Joachim Expelled from the Temple and Dream of Jaochim in the lunette; below, the meeting of Joachim and Anna, Birth of the Virgin and Presentation in the Temple, Her Marriage to Joseph. Certain of the male figures in the Presentation are doubtful portraits of the painter’s father, Gaddo Gaddi and Andrea Tafi, c. 1330

On the opposite (W.) wall, above a statue of Madonna by Vincenzio Dante (sculptor of the statue of Julius III. at Perugia) is a large fresco by S. Mainardi, showing the Madonna letting down the cintola, or girdle, to the ever-doubting Thomas, who kneels, aureoled, at her open sarcophagus, which is filled with flowers.

Next to the exit occurs a fine mid-fourteenth century Baroncelli tomb, with five-cusped canopy carried on twisted (tortellate) columns, having classic caps. It is, however, best admired from the other side the wall, where the centre is filled with an iron grille of quatre foils, within a rich sixteenth-century frame of stonework. The inscription below tells us that, in 1327, four brothers of the Baroncelli raised the chapel in honour of God and the Beata Annunziata.

We next enter the Chapel of the H. Sacrament, lit by an ugly square window. It consists of two bays with cross-vaulted ceilings. On the L. pier as we enter is a bronze plaque to Benedetto Varchi, historian of Florence, 1502–65; and within the chapel the monument of Alice, Countess of Albany (Stolberg), wife of the Pretender (1772), who later, having left him, married the poet Alfieri, and died at Florence in 1824. On pedestals in front of the pilasters dividing the chapel are two Franciscan saints by Della Robbia, of fine expression, especially that on the left. The frescoes on the walls to the right, all much damaged, represent episodes in the life of S. Nicolas of Bari; and, second bay, the life of S. John Baptist.

On the left wall, first bay, S. John the Divine; and, second bay, episodes in the life of S. Anthony.

We now descend five steps again into the transept, and in the floor, utterly neglected and unprotected, is, among others, the first-rate canopied effigy in high-relief of white marble of Biordi degli Ubertini (1353), showing that chain mail resisted the invasion of plate mail longer in Italy than in England.

The white marble cenotaph on the main pier of transept is that of Prince Neri Corsini who died of small-pox in London, 1859, while carrying on negotiations for the Grand-Duke Leopold II.

Let us now pass across the front of the choir to the chapels north of it.

- The Tosinghi-Spinelli-Sloane Chapel with modern frescoes by Martellini.

- S. Anne contains a monument to Pietro Nardini, an excellent violinist and composer of the Scarlatti school, 1725–96. On the two pilasters fronting the transept are bronze plaques commemorating Victor Emmanuel II. and Cavour, the great statesman.

- S. Antonio, has modern frescoes by the Sabatelli family.

- Has a fine fourteenth-century window containing SS. Mathias, Maurice, Stephen, and L . . . . ius. This is the Pulci Beraldi chapel, and contains frescoes by Daddi. A heavy stone chained to the right pilaster fell in 1698, but injured no one. Over the altar is a Madonna and Child enthroned with Angels, by one of the later Della Robbia firm. The arms depicted are, argent, gules, a barry of eight.

- S. Silvestro, also a Bardi chapel with a fine family tomb on left to Andrea dei Bardi (1367). The frescoes here, much damaged, represent episodes in the life of S. Sylvester. The lowest on the right gives with much character the triumph over the dragon in the Foro Romano which the Mirabilia tells us killed so many people in the time of Constantine, who is seen looking on at the miracle.

- Niccolini Chapel entered through a handsome cinquecento door with monolith columns of Sicilian jasper. The frescoes on the cupola are by Volterrano. It is quite a museum of Roman marbles, and will never look old. The statues are by Francavilla.

The spacious chapel with a long grille terminating the transept is also a (third) Bardi chapel, but is only interesting for its beautiful fourteenth-century glass, much of which is lamentably hidden by the altar, above which the Bardi shield, or and gules, is seen. The window in the left wall (W) has unfortunately been shortened at base, but it consists of two lights and a circular head, with the Bardi arms repeated. The panels contain kings and saints framed in exceptionally lovely armorial quarries of lions and popinjays, and shields with argent-gules, a barry of eight. Another fourteenth-century Bardi tomb flanks the fine grille on the W. side.

We next enter the Salviati-Borghese Chapel, containing a monument to Countess Zamoyska by Bartolini, and another to Vannucci by Pazzi. Vannucci was an ardent writer for the liberty of Italy, and librarian of the National Library. He died 1880. Against the transept pier stands Fantacchiotti’s cenotaph to the great composer Cherubini (1760–1842).

Below us, under all those handsome marble slabs, lie the Bardi, Sachetti, Taldi, Albergotti, Strozzi, and others.

Elevated portico to left, Pazzi Chapel center, begun 1441 (phot via Web Gallery of Art)

But let us now get a breath of the more open air by stepping across to the great cloisters, which are found through a door, usually open, near the fifth bay of the south aisle, formerly the chief entrance for the monastic processions here. Contrary to custom, we find ourselves standing in a long raised portico, some ten feet above the level of the cloister-garth—a device against the floods of Arno. Immediately beneath us we descend into the portico of Brunelleschi’s beautiful chapel. The cloisters, now united, were formerly two in number; the larger, built by Arnaldo di Lapo, is centred by a statue originally intended for the high altar in the Duomo which was removed thither in 1843. On our left is a marble sarcophagus of the early fourteenth century with the effigy of Gastone della Torre of Milan, Bishop of Aquileia in Dante’s time.

The unique Cappella dei Pazzi formerly served as a chapter-house, and not merely for the friars of the convent, but for those of the entire Order. It was raised at the cost of Andrea dei Pazzi, and dedicated to his apostolic name-saint. The façade consists of a Corinthian portico of four bays divided by a noble and lofty arch leading to the door of the chapel itself. The wall above these becomes an extended frieze, or screen, which in turn supports a low loggia covered by a leaning roof. Within, the walls are decorated by twelve Della Robbia medallions in white on blue, and above them is a Della Robbia frieze of lambs and cherubim running round the entire walls. The vaulting of the portico is also panelled with rosettes, and over the door are the Pazzi arms, two dolphins addorsed between five daggers.

Jacopo Pazzi had headed the conspiracy against the Medici in 1478, and after attempting to raise the people, had been captured in his escape, tortured, and hanged. It was said that he had cried in dying that he gave his soul to the devil; he was certainly a notorious gambler and blasphemer. When buried here the peasants believed that he brought a curse upon their crops, so the rabble dug him up, dragged his body through the streets, and finally, with every conceivable indignity, threw it into the Arno.

Edmund G. Gardner, Story of Florence, p. 243.

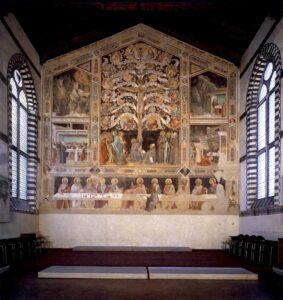

Taddeo Gaddi, Tree of Life and Last Supper, c. 1350, Great Refectory (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Beyond, through a beautiful door, by Brunelleschi likewise, is entered the Great Refectory, the walls of which are covered with frescoes by the scholars of Gaddi, illustrative of the lives of Christ, S. Francis, and S. Louis. Here are collected many objects of family and archaeological interest, including a fresco from the vanished Church of S. Maria Sopra Arno, attributed to Andrea del Castagno.

The Minor Refectory is frescoed by Giovanni di San Giovanni (1590–1636): S. Francis miraculously multiplying loaves. The library was taken to enrich the “Laurenziana” in 1766. In one of the chambers toward the Piazza the Holy Inquisition used to hold its sittings; and here, in 1328, Cecco D’Ascoli, astrologer, poet, and physician, was condemned to be burned outside the Porta S. Croce. Tommaso Crudeli, likewise a physician, was also condemned here.

The Inquisition here held its tribunals from 1284 to 1782, and practised appalling cruelties. Until the end of the XVIII c. the first cloister bore the inscription—“Qui si punisce quel che in Dio non crede e l’assicura nella vera fede.” [Here are punished those who don’t believe in God and the true faith is protected.] One or two instances are memorable.

Amongst the countless victims of this tribunal it is sufficient to mention Francesco Stabili, known as Cecco d’Ascoli, the philosopher, and astrologer of the Duke of Calabria, burnt in 1328, the victim of ecclesiastical ignorance and cruelty; Giovanni del Cane da Montecatini, burnt in 1450; Ludovico Domenichi, a literary man in the service of Cosimo I., condemned in 1547; Pietro Carnesecchi, given over to the Inquisition at Rome, which put him to death; Bartolommeo Panciatichi and Lucrezia Puccisma his wife, condemned in 1552; Galileo Galilei, infamously compelled to retract the sublime opinions which have been so much valued by those who came after him; Canon Pandolfo Ricasoli, condemned in 1641, for immorality, to the loss of all his goods and to perpetual imprisonment; Domenico Passerini, imprisoned for life in the fortress of S. Martino in Mugello in 1692. The last victim was the illustrious Tommaso Crudeli, the brilliant poet. It was his imprisonment which caused the famous senator, Giulio Ruccellai, to demand the suppression of the tribunal. It was eventually done away with by the Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo I., by a law of July 5, 1782.

Luigi Passerini.

Cecco d’Ascoli, while at Bologna, a university whose learned atmosphere was suspected of being full of perilous stuff, had published a commentary on “De Sphæra Mundi” by Sacrobosco (John Holiwood), for which he had been cited and reprimanded in the Convent of S. Domenico in that town. He was also a practising physician there, and it is shrewdly to be suspected that a father and son, Dino and Tommaso del Carbo, rival practitioners, undertook his ruin. He, however, escaped with his life. This was in 1324. In May 1327 we find him appointed Court astrologer-physician at Florence to Charles, Duke of Calabria, and enjoying the reputation of a vain and bitter man, a despiser of women, a clever prophet, and an open mocker of the lately deceased national poet, Dante. Unfortunately, his former rival Dino was likewise practising in this city of thorns and roses; and at Court, the Bishop of Aversa procured his dismissal on the ground of being a fatalistic philosopher; and presently appeared on the Tribunal bench at S. Croce, before which the wretched Cecco was charged with being a relapsed heretic in July: “Pieno di eresie, falsita ed inganne.” [Full of heresies, falsehood and deceit] His doom was pronounced September 15, and next day all Florence flocked to the place of execution, called “Africa,” just beyond the neighbouring walls of the city, many expecting that spirits might come down and carry off the astrologer from the flames, which were fed by the MSS. of his condemned works, including L’Acerba, his poem.

It was in the Convent of S. Croce that Sixtus V., as a monk, went stooping as if in decrepitude, “looking for the keys of S. Peter.”

The “Dormitorium” has vanished. The Second Cloister is used for barracks.5Although both the 6th and 9th editions of Florence note that “The Second Cloister is used for barracks,” this is no longer the case.– Ed.It was designed by Brunelleschi.

Around the pleasant Cloister are monuments of minor Tuscan celebrities.

There is nothing more Florentine in Florence than these old convent courts into which your sight-seeing takes you so often. The middle space is enclosed by sheltering cloisters, and here the grass lies green in the sun the whole winter through, with daisies in it, and other simple little sympathetic weeds or flowers; the still air is warm, and the place has a climate of its own.

W. D. Howells, Tuscan Cities, pp. 65–66.

Let us now return to the church, and view the splendid windows in the choir.

The Choir-windows consist of three lights of twelve panels, of beautiful early fourteenth-century glass. Opera-glasses alone can reveal its full interest, though its effect is easily appreciated.

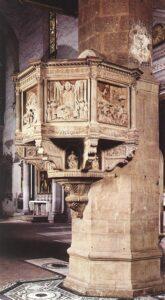

Benedetto da Maiano,

Pulpit, 1480-85 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The Pulpit attached to the third pier of the nave is a masterpiece of Benedetto da Majano, in white Serravezza marble, adorned with reliefs in five panels, representing: (1) Confirmation of the Order of S. Francis; (2) Burning of heretical writings; (3) the Stigmata; (4) Death of S. Francis; (5) Martyrdom of Franciscan friars in Mauretania. Beneath are small niches containing figures of Faith, Hope, Charity, Fortitude, and Justice.

Desiderio da Settignano, Tomb of Carlo Marsuppini, 1453-64 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

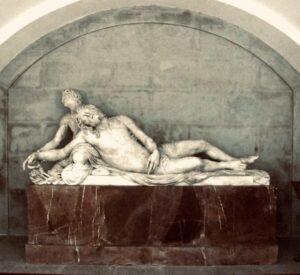

The Monuments, of which few have conspicuous merit, are nevertheless memorials of many of the most illustrious sons of Florence, many of whom repose in their last sleep below them. Far the most beautiful is that of Carlo Marzuppini, 1453–64, the masterpiece of Desiderio da Settignano, near the end of the N. aisle.

Marzuppini was born in 1399 at Arezzo, became a Greek scholar and Professor of Rhetoric at Florence 1434, and ten years later Secretary to the Signoria. He translated some of the Homeric poems, died in 1453 and was accorded a public funeral.

This is one of the three finest tombs in Tuscany—the best example of the delicate, sweet, and captivating manner of its sculptor. Desiderio has represented Marsuppini dressed as a civilian, with a book upon his breast, lying upon a sarcophagus, whose base, at each end of which stand genii holding shields, is adorned with sphinxes, festoons, and various ornamental devices; the arched recess in which the monument stands is crowned by a flaming vase, with the graceful angels holding festoons which fall upon the sides of the arch. The lunette contains a group in alto-relief of the Madonna and Child adored by angels. Although every part of its surface is covered with elaborate ornament, yet, owing to the exquisite delicacy with which its details are sculptured, the effect of the whole mass is extremely rich without being overloaded.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, pp. 173–74.

Bernardo Rossellino, Tomb of Leonardo Bruni, 1446-48 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The tomb of his predecessor, Leonardo Bruni, also an illustrious Aretine, who enjoyed the Medici’s favour, is nearly opposite in the S. aisle.

Antonio Canova, Tomb of Vittorio Alfieri, 1804-10 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

In the S. aisle will be easily found Canova’s huge monument to C. Alfieri, the poet, placed there by the Duchess of Albany, his widow (1749–1803).

Innocento Spinazzi, Tomb of Machiavelli, 1787 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

In the pavement of the third bay is a stone recording the spot where lie the remains of Ugo Foscolo (1776–1827), author of I Sepolcri (1807), an officer in the army collected by Napoleon for the invasion of England. Foscolo emigrated thither in 1816, and died in Chelsea, having become a teacher of Italian and lecturer on the literature of his land.

Near by is the cenotaph to Machiavelli (1469–1527) by Spinazzi, placed here in 1787. Statesman, diplomatist, and masterly writer, Secretary of State for fourteen years; banished in 1512, when he wrote “Il Principe” in retirement, for the use of Lorenzo de’ Medici.

His History of Florence is enough to immortalise the name of Machiavelli; seldom has a more gigantic stride been made by any department of literature than by this judicious, clear, and elegant history.

Henry Hallam, Introduction to the Literature of Europe, vol. 1, p. 564.

Near the First Altar of this aisle is Vasari’s monument to Michelangelo Buonarroti, the bust being by B. Lorenzo (1475–1564). Pius IV. wished the body buried in Rome, where the master had died, but the Florentines hastily carried it away by night, and brought it here.

On the pier opposite is a stoup for holy water, above which is a Mandorla, or almond-shaped glory, containing a beautiful Madonna and Child, encircled by cherubim, and placed there by the Nori in memory of their illustrious kinsman, Francesco, a Prior of the Republic, who during the murderous attack on Lorenzo dei Medici by the Pazzi in the Duomo, hurled himself between him and the assassins, and so received his death-blow. Leo X. gave Indulgence to all who prayed for Nori’s soul. The work is by Ant. Rossellino (1427–79).

Stefano Ricci, Cenotaph of Dante, 1818-29 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The monument to Dante will scarcely interest those who have visited Ravenna, where his remains lie in “the little cupola more neat than solemn.” [Lord Byron, Don Juan, Canto 4] It is by Ricci (1829). A bronze tablet commemorates, next, Mazzini (1805–72), the ardent and dexterous patriot, who achieved so well for the independence and unity of Italy, and met with constant encouragement in England, where he spent some years. Opposite the fifth pier of the same aisle (going toward the transept) is a medallion to Abbé Luigi Lanzi, the historian of Italian painting, a Jesuit scholar, who founded the excellent Etruscan Museum, and died in 1810. Opposite the sixth pier is a slab marking the spot where lie the remains of Rossini(1792–1867), brought from Paris in 1886.

Beyond the door of the north aisle is the tomb of Fossombroni, minister to the Grand Dukes Pietro Leopoldo and Ferdinando III., ob. 1844. Then a plaster monument, with a statue, commemorates Donatello. Lastly we reach the tomb of Angelo Tavanti, the jurist, 1781; of the learned Pompeo Signorini, 1812; of the historian, Giovanni Lamio; and the monument of Galileo by Foggini. In the centre of the nave is a flat tomb, with an incised figure and mosaic border, to John Ketterick (spelt Catrick), Bishop of Exeter, who died here in 1419, on a mission from Henry V. to Pope Martin V. Many others of the monumental slabs and incised figures let into the pavement are deserving of study, especially one in bold relief of “a Galileo of the Galilei, who in his time was head of philosophy and medicine, and who also in the highest magistracy loved the Republic marvellously.”

Left of the main entrance is the tomb of the learned Gino Capponi, author of the Storia della Repubblica di Firenze (1884).

The Via de’ Malcontenti (so called because criminals were led along it to execution), on the north of S. Croce, contains at its farther end the Pia Casa di Lavoro, or Work-house, erected on the site of two convents, the Monte Domini and the Monticelli.

It was in the old convent of Monticelli that Piccarda Donati, the sister of Corso Donati, and a cousin of Gemma Donati, the wife of Dante Alighieri, took the veil, as Sister Costanza. Piccarda became a nun to avoid a marriage with Messer Rossellino della Tosa; but her father, Simone Donati, and her brother Corso carried her forcibly from her refuge, and insisted on her union with Della Tosa. No sooner had the marriage ceremony ended, than Piccarda threw herself on her knees before the Crucifix, entreating for protection, when she suddenly became so ill that her father was constrained to yield to her request, and to send her back to her convent, where she died in eight days. Dante has placed Piccarda in Paradise in the moon, or lowest heaven, reserved for those who have involuntarily broken their vows.

Susan & Joanna Horner, Walks in Florence, 2nd Ed. vol. 2, p. 77.

No. 7 has an interesting coat-of-arms on a shield: Per pale, a demi-griffon holding a star, and in base, chequy impaling a chevron between roses, “in sublime.”

The next street which runs parallel to the “Malcontenti” is the Via Ghibellina, named, in 1261, after the Ghibelline victory at Monte-Aperto. Here was the Convent of S. Maria delle Murate, whither the famous Caterina Sforza, Duchess of Forli, commonly called “La Madonna di Forli,” retired in 1498, and continued to reside till her death in 1509. She had, though only in her thirty-ninth year, survived her three husbands—Girolamo Riario, nephew of Sixtus IV., murdered 1488; Giacomo Feo, murdered 1495; and Giovanni de’ Medici, by whom she was the mother of Giovanni delle Bande Neri, 1498. She had undergone numerous sieges, and been cruelly imprisoned for a year in the castle of S. Angelo.6She was the direct ancestress of Alfonso XII. of Spain. She was buried in the convent chapel, but her tomb was wilfully broken up, and her remains thrown away (!) on the recent conversion of the building into a State prison (1832–1983). Here, in 1529, Catherine de’ Medici was placed under the protection of the nuns, being then only seven years old. Since 2002 the former nunnery and prison has housed the Faculty of Architecture and a museum.

In the Via Allegri, which crosses the Ghibellina, was the studio of Cimabue (1240–1300), who, says Vasari, “gave the first light to the art of painting.” His most important works remain in his native city.

Cimabue knew more of the noble art than any other man; but he was so arrogant and proud withal, that if any one discovered a fault in his work, or if he perceived one himself, he would instantly destroy that work, however costly it might be.

Anonimo [anonymous] commentating on Dante.

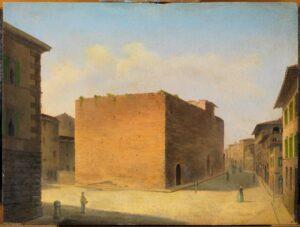

Fabio Borbottoni, View of the ancient Isola delle Stinche

The Accademia Filarmonica and the Teatro Verdi (formerly the Pagliano Theatre), in the Via Ghibellina, occupy the site of the historical prisons, called the Stinche, demolished in 1838. Telemaco Bonaiuti designed the Neo-Classical theatre for Girolamo Pagliano. The new theatre opened with a performance of Verdi’s Rigoletto in September 1854. On the stairs of the Accademia is a curious fresco called the “Scimia della Natura,” attributed to Giottino: it is an allegory relating to the expulsion of the Duke of Athens. A tabernacle, on the exterior of the Accademia, of a merchant bestowing alms upon the prisoners, while the Saviour and angels look on, is by Giovanni di San Giovanni.

In the neighbouring Via del Fosso (named from its position on the moat of the early city) is the Palazzo Conte Bardi, a graceful work of Brunelleschi. Here, in an orange garden opposite the theatre (now destroyed), the handsome page, Lelio Torelli, beloved by Isabella, daughter of Cosimo I., was murdered by her jealous husband, Troilo Orsini. This story is the subject of Guerazzi’s novel Isabella Orsini.

Santi Simone e Giuda (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Behind the Teatro Verdi is the little Church of S. Simone, founded in 1202, restored by Silvaniin 1698, where Raffaellino del Garbo is buried. Some women were burnt for heresy in its little piazza, February 14, 1551.

Casa Buonarroti (photo Casa Buonarroti Museum)

Opposite the Teatro Verdi (No. 64 Via Ghibellina) is the House of Michelangelo Buonarroti (No. 70), which, in 1858, was bequeathed to the city of Florence by Cosimo Buonarroti, a descendant of the brother of the great master.

The Casa Buonarroti contains a Battle of Hercules and the Centaurs and the Madonna of the Steps, bas-reliefs that Michelangelo executed while still a youth. Vasari highly praised both works, but Hare found the former to be “a hopelessly confused and ugly relief.”

At this time and by the advice of Politiano, Michelagnolo executed a Battle of Hercules with the Centaurs in a piece of marble given to him by Lorenzo [the Magnificent], and which proved to be so beautiful, that whosoever regards this work can scarcely believe it to have been that of a youth, but would rather suppose it the production of an experienced master. It is now in the house of his family, and is preserved by Michelagnolo’s nephew Lionardo, as a memorial of him, and as an admirable production, which it certainly is. Not many years since, this same Lionardo; had a basso-rilievo of Our Lady, also by Michelagnolo, and which he kept as a memorial of his uncle; this is of marble and somewhat more than a braccia high; our artist was still but a youth when it was done, and designing to copy the manner of Donatello therein, he has succeeded to such an extent that it might be taken for a work by that master, but exhibits more grace and higher powers of design than he possessed. That basso-rilievo was afterwards given by Lionardo to Duke Cosimo, by whom it is highly valued, and the rather as there is no other basso-rilievo by his hand.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 4, pp. 45-6.

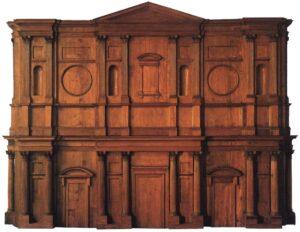

Other works by Michelangelo include a wooden model for the façade of San Lorenzo that was never executed; a reclining river god, perhaps intended for the New Sacristy; a collection of drawings shown in rotation; and a number of small sculptural bozzetti including a wax model for the David, and some autographs of the sculptor.

To celebrate the life of his great uncle, Michelangelo Buonarotti the Younger commissioned the leading artists of his time then resident in Florence to decorate the ceilings and walls of a suite of four rooms. Completed between 1613-37, the artists included Artemisia Gentileschi, Jacopo da Empoli, Domenico Passignano, and Pietro da Cortona.

Michelangelo’s pupils, in perpetual testimony of their admiration and gratitude, have ornamented his house with all the leading features of his life; the very soul of this vast genius put in action. This is more than biography!—it is living as with a contemporary.

Isaac Disraeli, Curiosities of Literature, vol. 3, p. 399.

Oratory of SS. Procolo e Nicomede (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

In the neighbouring Via Giraldi were the houses of the historic chronicler-family, the Villani.7Giovanni, Matteo, and Fillippo. The Oratory of SS. Procolo e Nicomede is a relic of one of the oldest churches in Florence. At the end of the Via Ghibellina we again find ourselves at the Bargello, opposite which were the houses of the powerful Counts Gondi of the Casentino.