5.1: SS. Apostoli, Or S. Michele, Mercato Vecchio, Piazza della Repubblica, Bigallo

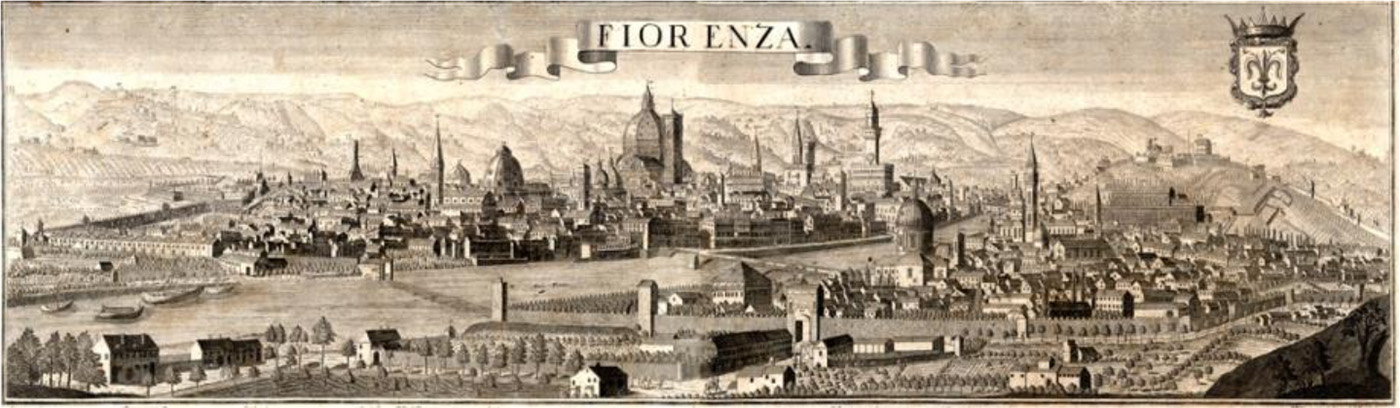

LEAVING the Piazza S. Trinità at the back of the Palazzo Ferroni, called, until 1871, the Palazzo del Municipio, the narrow street called Borgo degli SS. Apostoli leads toward the Uffizi. It was remarkable as containing the houses of the Buondelmonti. One of their towers is still seen.

Santi Apostoli Façade (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The little Church of the S. Apostoli (right, in the Piazza del Limbo), whose foundation is apocryphally attributed to Charlemagne, was much admired and studied by Brunelleschi. The sixteenth-century square door-frame of black and white marble belies its date, which probably reaches back to the XI. c. Once known, this little church will be loved. It consists of a nave and aisles of seven bays, with black marble columns, red-tiled, with a railed-off choir and bold apse, and a chapel at the end of each aisle, besides lateral altars. It is a mausoleum of the Altoviti family, whose erect white wolf (argent on sable) frequently occurs on the slabs. The Acciajuoli are also buried here in numbers. In front of the altar lies Dardano Leone degli Acciajuoli, while at the head of the N. aisle is the tomb of Neri dei Donati de’ Acciajuoli.

Andrea della Robbia, Altar of the Sacrament, 1512 (photo Web Gallery of Art)

The altar beyond has an exceedingly beautiful work by Luca della Robbia’s successors, a Ciborium with angels drawing aside curtains, the old motive of Arnolfo, well used after two centuries. On the wall, near by, is the splendid tomb to Oddo Altovitiby Benedetto da Rovezzano (1507), consisting of a sarcophagus richly sculptured beneath a noble canopy. At the head of the opposite (or south) aisle is a dark marble door leading into the sacristy and former cloister. Above it is the tomb of Bindo Altoviti (1570) by Ammanati. Over the altar rails are fine relief effigies of 1392 of Stuldo Altoviti, and his son. In the cloister-arcade vaulting occur the arms of Andrea di Domenico Fiocchi, Prior in 1452, which gives us the date of their erection, i.e.: Per fesse, a dragon, above a barry of three. Here is also a Carducci tomb. In the sides of the apse are busts of Charlemagne (so-called) and an Archbishop of the Altoviti family by Caccini.

In the little Romanesque church of Saint Apostoli there is a tabernacle of such exquisite taste, both for the general design and for the details of the ornamentation, that it would be impossible not to see a work there, and even one of the best works, by Luca della Robbia, if the heavy garland, in dull colours, which falls on both sides, did not show a hand much less skilful and less delicate than that which made the two angels, whose beauty first strikes the eyes. This first impression is further strengthened by the kind of luminous glaze with which the figures and the mouldings seem coated, as a result of the tints left there by the gilding with which they are enhanced, and of which we can still see some trances. Now, we know that this additional process was practiced by the head of the family; and this is one more reason to regard this delicious monument as a joint work of uncle and nephew.

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, vol. 1 (1861), p. 411.

Benedetto da Rovezzano, Palazzo Altoviti-Sangalletti (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

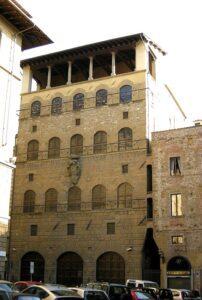

The Palace of the Altoviti (Nos. 10–14) south of the church, bearing their arms (sable, a wolf erect, argent) is by Benedetto da Rovezzano. The Altoviti family was founded in Florence by a Ghibelline knight in the time of Frederick II. [The palace was the home of the legendary Caffè Doney frequented by the Scorpioni, a group of elderly English ladies in the 1930s and ‘40s known for their sharp wit. The Doney is featured prominently in Franco Zeffirelli’s 1999 film Tea with Mussolini. — ed.]

Baccio d’Agnolo, Palazzo

Borgherini-Turco, c. 1517 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The adjoining Palazzo del Turco or Borgherini (No. 15) was built by Baccio d’Agnolo. In its anglewall is a lovely relief of the Virgin and Child by Rovezzano, and at the corner of the building wrought-iron torch-holders. The art-treasures of this house were courageously and successfully defended in 1529, against the agent of the King of France, by Margherita Acciaiuoli, who declared that she would spend the last drop of her blood in defence of that which had been her father-in-law’s wedding-gift. Some of the best pictures in the Pitti came from this palace.

This street enters that of the Por (Porta) Santa Maria, just under the old Tower of the Palazzo Lambertesca, the rallying-place of the Amidei,1Arms: Or, a fess, gules. so celebrated in their feuds with the Buondelmonti,2Arms: Az., a monte with six summits, gules, topped with a Latin cross. (Varielles). and by whom young Buondelmonte was slain.

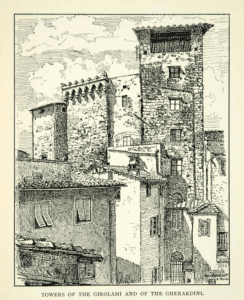

Opposite is another highly picturesque old tower—Torre de’ Girolami3The Girolami possessed the ring of S. Zenobio, which was supposed to have rare healing power. Lorenzo il Magnifico sent it in 1482 to Louis XI. of France, who was seriously ill, and who, on his recovery, returned it in a golden box filled with precious stones, by the sale of which the Girolami founded a canonry for the cathedral of Florence.—once the dwelling of San Zanobio, and still decorated with flowers on his festa. The tower was badly damaged in August 1944 as the Germans retreated, but it has been rebuilt. These towers are, of course, relics of the period before the rule of the Medici, when the population of Florence was divided into three classes—the Grandi, the Popolani, and Plebe.

Santo Stefano (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

A little beyond this, on the right, looking on to a trapezoidal court, is the ancient Church of S. Stefano al Ponte, called “ad Portam Ferream” from its iron gate, upon which may be seen the historic horse shoe of the palfrey of Buondelmonte. The façade has its square-headed central door of black and white marble, with a circular light in the tympanum. Around this marble frame runs a lozenge border. The side doors are no longer walled up. The upper half is later work, finishing with a pretty corbelled gable-cornice. Here, in 1218, the Amidei met to arrange the murder of Buondelmonte. The church was deconsecrated in 1986 and is currently a performance venue called the Cattedrale dell’Immagine.4S. Stefano was much damaged by the 1966 flood. In 1993 a mafia bomb damaged the building. It contains many monuments of the Bartolomei family, who succeeded the Girolami at the old house in the Via Lambertesca, and restored the church in 1656. In the choir is a statue of S. Stephen by Guercio del Gambasso (the squint-eyed), the master of Luca della Robbia. A curious renaissance staircase by Buontalenti recently removed hither (1895) from S. Trinità is the feature of the church.

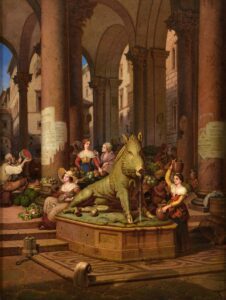

The Via Por San Maria leads (left) to the Mercato Nuovo, with a loggia built by Battista del Tasso for Cosimo I. in 1547. Its niches have been recently filled with statues of famous Florentines. On one side is a fountain with a bronze boar, copied from an ancient marble one in the Uffizi, by Tacca, a pupil of Giovanni da Bologna.5Today the boar in the Mercato Nuovo is a 1998 copy of Tacca’s original, which is in the Stefano Bardini Museum.

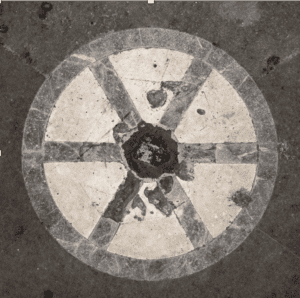

Bankrupts were formerly compelled to sit on the round marble slab in the centre of the market. It served as their asylum. It represents a wheel of the Carroccio.

In the middle, on the ground, is a circular space formed of marble slices, alternately white and black, and regularly cut by six radii, in memory of the ancient war chariot, the carroccio, which the republic dragged to all battles, and which was stored there before the construction of the market. When the carroccio was no more, this same place was put to a singular use. Bankrupts, by virtue of an ancient custom, had to strike this confined space three times with their bare butts before obtaining their concordat. From the way the stone is worn, we can guess that it has been used a few times.6See the verses of the Tuscan poet Lippi, in allusion to this custom.

In the middle, on the ground, is a circular space formed of marble slices, alternately white and black, and regularly cut by six radii, in memory of the ancient war chariot, the carroccio, which the republic dragged to all battles, and which was stored there before the construction of the market. When the carroccio was no more, this same place was put to a singular use. Bankrupts, by virtue of an ancient custom, had to strike this confined space three times with their bare butts before obtaining their concordat. From the way the stone is worn, we can guess that it has been used a few times.6See the verses of the Tuscan poet Lippi, in allusion to this custom.

Louis Simonin. Les Anciens Banquiers Florentins, p. 653.

From the corner of the Mercato the Via Capaccio leads to the Church of S. Biagio, now used for firemen. It occupies the site of and partly incorporates Santa Maria sopra Porta, where the Carroccio, or war-chariot, was kept, and where its bell called “La Martinella” the “Little Mars” tolled continuously before the commencement of a war. Here the earlier captains of the Guelf party used to hold council. The adjoining palace, afterwards used for the Guild of Silk, belonged to the Lamberti, descended from a German baron, who came into Italy with Otho II. in 962; their arms were six golden balls on an azure ground, whence the lines of Dante—

e le palle dell’ oro

Fioran Fiorenza in tutti i suoi gran fatti.

and how the Balls of Gold

Florence enflowered in all their mighty deeds!

Dante Paradiso 16:110–11. Trans. Longfellow.

Every Thursday there is a flower market here.

E. and W. of the Mercato Nuovo runs the Via Porta Rossa(so called from a gate which existed in the first circuit of the walls), which leads into the Piazza della Signoria. Cennini who introduced printing into Florence lived at No. 3.

Palazzo Davanzati, c. 1350 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

At No. 13 is the Museo di Palazzo Davanzati, (converted into a charming museum for things mediæval by Professor Volpi), formerly Davizzi, of the XIV. c., with a shield of arms wrongly attributed to Donatello in its court, and, above, a loggia of five bays. No fewer than forty-four priors and ten gonfalonieri were of the Davanzati7Arms of Davanzati: Az., a lion, or, clawed and tongued, gules. family, also many famous warriors and ambassadors, and the historian Bernardo Davanzati. Beneath it in XV. c. were the three wool shops of this rich family. In 1904 Elia Volpi an antiquarian and art dealer, purchased the building and filled it with art and objects such as would have been found in a noble’s quattrocento home. However in 1916, six years after opening the refurbished palace as a museum, Volpi was forced to liquidate its contents. In the introduction to the auction sale catalogue, Volpi noted that he had previously cited “the unhappy state of Europe which has forced me to disperse the gatherings of years, and gave the reasons for my determination, not only that my collection should be sold at public auction, but that the sale should take place in America.”8WWI, which had begun in 1914, was ongoing. The auction catalogue is a fascinating document, especially the one at Princeton, which contains hand-written notes of the naming the buyers and prices realized. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101075991495&view=1up&seq=17 Eventually the property was acquired by the State, which had been Volpi’s intention, and the noble interior has been recreated.

Opposite to it a cleared space opens out toward the Strozzi Palace. No. 13 (the Hôtel Porta Rossa) has bracketed projecting storeys. The Via Monalda, opposite, is named from the towers of the Monaldi9Arms of Monaldi: Gules, a peacock, in profile. family, of whom Buonfigliuolo was one of the seven founders of the Servi di Maria. The other, or eastern part of the street, was formerly called Via dei Cavalcanti, from the illustrious Guelphic race whose houses stood there.10Arms of Cavalcanti: Arg, semee with crosslets, gules. Of this family was that Guido, considered by Dante to be a better poet than his rival Guido Guinicelli: —

Cosi ha tolto l’uno l’altro Guido

La gloria della lingua.

So has one Guido from the other taken

The glory of our tongue

Dante Purgatorio 11:97–98. Trans. Longfellow.

In the overthrow of the nobles by the people after 150 years of struggling, in the reforms decided upon after the expulsion of the Duke of Athens (1343), the houses of the Cavalcanti, Pazzi, and Donati were taken. The people then assailed the palaces of the Rossi, Bardi, Manelli, and Nerli, which extended in an almost unbroken line along the S. bank of the Arno from the [Ponte] alle Grazie to the [Ponte] alla Carraia, and those of the Frescobaldi and Rossi, which stood in the street now known as the Via Maggio and in the Piazza de’ Frescobaldi. The attacking party, although reinforced, was repulsed with great slaughter. But the attack was renewed, and the houses of the Frescobaldi and Rossi were captured. The Bardi alone held out, but were finally compelled to yield. Not less than twenty-two of their houses were burned to the ground.

F. A. Hyett, A History of Florence(1903), pp. 134–35.

Turning to the left, we now enter the Via Calzaioli, or “StockingMakers’ Street”11The Florentine serge-stockings calze di rascia had long a great reputation. Charles V. wore a pair when he made his entry in 1536. (originally Corso degli Adimari). One of this family seized Dante’s goods.

Calzaioli will always talk if you will listen—here on the stones that are still called the Song of the Lily it has heard the soft footfall of Ginevra’s bare and trembling feet; here, where Guardamortà rose, it saw the lion tremble before a mother’s love; here in its workshop the Bronzino dwelt, and here, in its church, his bones were laid to rest; here Donatello and Michelozzo laboured for the love of arts and men hard by yonder against the little Bigallo; here flame and steel ravished their worst after red Arbia; here the White Bands shivered and fled before their old hereditary foes; here, on Ascension Day, the Signoria went up with the gold and purple of ripe fruits, to lay them at the feet of that Madonna of Ugolino whose manifold miracles sustained the soul of Florence beneath the Devil’s Plague; here, on the Feast of Anna, it saw Walter of Athens driven out of the city, and all good men and true trooping thither to render her thanksgiving, and all the Arts raising in memory the statue of their patron saint and the shields of their blazonries—all these things, and a million more, has Calzaioli seen since its old towers and casements crowded hard on one another.

Ouida. Pascarèl, vol. 3, pp. 195–96.

Orsanmichele, N.-E. corner (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

On the left rises the famous building called S. Michael of the Garden, Or San Michele, erected in 1337 (on the site of a loggia and granary for the storage of corn, built in 1280 by Arnolfo di Cambio), in order to shelter a miraculous image of the Madonna by Ugolino da Siena upon one of its piers, which had survived the fire of 1304, and become an object of intense popular reverence. For two centuries after the ground storey had been transformed into a church, the upper storey of the building continued to be used as a granary.

Or San Michele was held in such veneration that strict laws were passed prohibiting any noise in its vicinity. No gambling was allowed within a prescribed limit, and the infringement of these rules was punished by a fine; and if it was not paid, the defaulter was either imprisoned for a month in the stinche, or he had to undergo what was called baptism—namely, immersion several times in the Arno from one of the bridges.

Susan & Joanna Horner, Walks in Florence, vol. 1, pp. 175–76.

Its predecessor, built by the great Arnolfo, was destroyed by fire in a faction riot which raged round it in 1304 between the Neri and Bianchi, when Villani says that, owing to the wind blowing hard, more than 1700 houses were burned. The Cavalcanti and Gherardini were the greatest sufferers, as almost the whole of their property perished in the flames. Indeed, the losses sustained by many old noble families were so great that the final extinction of their supremacy may be said to date from this conflagration.

F. A. Hyett, A History of Florence, p. 74.

But the pilaster with Madonna’s picture had survived the fire, and the Laudesi (special worshippers who sang “lauds” to their lady of Or S. Michele) still met around it to sing her praises. But in 1336 the Signoria proposed to erect a grand new building on the site of the old loggia, which should serve at once for corn exchange and provide a fitting oratory for this new and growing cult of the Madonna di Orsanmichele. The present edifice, half palace and half church, was commenced in 1337 and finished at the opening of the 15th century.

Edmund G. Gardner, Story of Florence, p. 189.

The direction of works was entrusted to the Guild of Silk Merchants, and Taddeo Gaddi probably gave the design, which was that of a Loggia dei Mercanti, or open arcaded basement for the dealers, and an upper “magazzino” for the storage of the grain. It was, in fact, a magnificent “Horreum,” though “Or” and “Horreum” have nought here to do with one another, except in over-naive Teutonic minds. But, like most great mediaeval building projects, this one drew in many architects, with resultant modifications of the original design, as well as expansions, possibly with Gaddi’s own approval. These, in this case, were made by Andrea Orcagna and Simone di Francesco Talenti. As it lifts its solemn, grey beauty into the blue Florentine air, with the grandeur and tranquillity of a sovereign who forgets everything but his maker, let us take note of its exterior form just sufficiently to be able to rebuild it afterwards in our mind’s eyes. Ancient though it is and lovely, Dante never saw it. Boccaccio did, and Niccolò Acciajuoli did, while St. Catherine of Siena must have beheld it in all its freshness.

Orsanmichele (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

It rises, two bays wide, by three deep N. and S., in three sections, or storeys, of (c.) forty-five feet apiece. In each bay of the ground tier is a round-headed triple window, carried on graceful light shafts up to elaborate and exquisite head-traceries. Between these bays (not within them), on broad pilasters, occur marble-canopied niches, cusped and crocketted—except the central eastern one, which is much later, and square-headed, with a pediment. Each niche has its bronze statue, representing the patron saint of one or other of the major or minor arts, although only six out of fourteen of the latter are provided for. Above these various niches occur circular plaques or “tondi,” bearing the insignia of the art to which the niche belongs. Higher up, the spandrels are adorned with appropriate medallions by Luca della Robbia. The windows in the upper storeys are biforate only, but worked in white marble within round-headed Serena frames. At the summit juts out a noble-traceried corbel-cornice, giving splendid finish to the effect.

It is entered from the west, and should be examined on a bright morning. The nature of the building as a “Loggia dei Mercanti” becomes revealed if, in imagination, we take away the various side altars and organ-gallery, and throw open the walls between the piers to the street.

Excepting Donatello’s S. George, which is now in the Bargello, the original statues erected by the various Guilds are housed in a museum located on an upper floor of Orsanmichele. Beginning with the East Face, copies of the sculptures are:—

East Face (Via del Calzaiuolo)

Lorenzo Ghiberti, S. John Baptist, 1413–16 (L’Arte di Calimala (Guild of Foreign Wool-Merchants)) (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Andrea Verocchio, Incredulity of S. Thomas, 1473–83 (Tribunal of the Mercanzia)) (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

South Face (Via dei Lamberti)

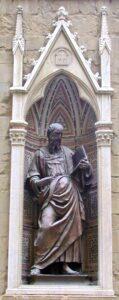

Donatello. S. Mark, 1411 (L’Arte dei Linajuoli (Flax Merchants)) (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Nanni di Banco, S. James, c. 1422 (L’Arte dei Vajai (Furriers )) (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Piero di Giovanni Tedesco, Madonna of the Rose, 1399 (L’Arte di Medici e Speziale)) (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Baccio di Montelupo, S. John the Evangelist, 1515 (L’Arte di Seta (Silk Merchants)) (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

S. John the Evangelist as an old man—very unusual in art.

Michelangelo stopped before the statue of S. Mark by Donatello, and, in allusion to its animated expression, exclaimed, “Mark, why don’t you speak to me?”

J. S. Harford, Life of Michael Angelo, vol. 2, pp. 223–24.

West Face (Via dell’Arte della Lana)

Lorenzo Ghiberti. S. Matthew, 1419-20 (L’Arte del Cambio (Stockbrokers)) (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Lorenzo Ghiberti. S. Stephen, 1425–29 (L’Arte della Lana (Guild of Wool)) (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Nanni di Banco. S. Eloy (Eligius), 1411-15 (L’Arte dei Maniscalchi, e degli Orafi (Blacksmiths)) (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The admirable statuettes relating to the Annunciation, on either side of Ghiberti’s S. Matthew, are by Niccolò di Piero de Lamberti di Arezzo.

This lovely figure [Ghiberti’s S. Stephen] is reminiscent of one of the frescoes in the chapel of Pope Nicholas in the Vatican.

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, vol. 1 (1861), pp. 303–304.

North Face (Via Orsanmichele)

Brunelleschi, S. Peter, 1415 (L’Arte dei Beccai (Guild of Butchers)) (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Nanni di Banco, S. Philip, c. 1410–12 (L’Arte dei Conciapelli (Tanners)) (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Nanni di Banco. Santi Quattro Incoronati, 1408 (L’Arte dei Maestri di Pietra e Legname (stonemasons and carpenters)) (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Donatello, S. George, 1415–17 (L’Arte dei Medici e Speziali (Physicians and Apothecaries)) (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Santi Quattro Incoronati [Four Crowned Saints] were martyred under Diocletian.

When the saints were finished, Nanni discovered that they were too big for the niche destined for their reception, and in despair consulted Donatello, who promised to help him out of his trouble, if he would give a supper to him and his workmen; to which Nanni joyfully consented. Donatello set to work, and after knocking off portions of the shoulders and arms of the four saints, brought them into such close contact that they could be placed in the niche without difficulty.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, p. 158.

Donatello was at first asked to make this statue, but the Hosiers considered the price he asked exorbitant, and therefore commissioned Nanni; such, however, was their confidence in Donatello’s probity that they consulted him as to what they should pay his substitute. To their surprise, he named a sum exceeding that which he had asked for himself; and when they remonstrated, he replied that, as Nanni was less experienced, he would find more difficulty, and require to give up more of his time to the work, which ought therefore, in justice, to receive higher remuneration.

Susan & Joanna Horner, Walks in Florence, vol.1, pp. 181–82.

This statue is not free from a certain stiffness, which betrays inexperience rather than a lack of inspiration.

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, vol. 1 (1861), p. 303.

Donatello. S. George of the Armourers, occupying the place of the Madonna of Simone da Fiesole, now inside the church. Given by the Physicians and Apothecaries (L’Arte dei Medici e Speziali).12S. George has recently been taken by the authorities from the church to which he was presented five hundred years ago, and from the people who valued his daily companionship. He is now imprisoned in the Bargello, where his friends must pay a franc to interview him. As it is hoped that public opinion may bring about the restoration of the statue, his niche is not described as empty. [A copy occupies the niche (1903).] S. George is in complete armour, without sword or lance, bareheaded, and leaning on his shield, which displays the cross. The noble, tranquil, serious dignity of his figure admirably expresses the Christian warrior; it is so exactly the conception of Edmund Spenser13The Faerie Queen 1:1 that it immediately suggests his lines:—

For sovereign help which in his need he had.

Right faithful, true he was, in deed and word;

But of his cheere did seem too solemn sad;

Yet nothing did he dread, but ever was ydrad.

Quoted by Anna Jameson, Sacred Art, vol. 2, p. 404.

The interior of the church is filled with beauty and glowing with harmonious colour. The windows have rich remains of stained glass. The faded frescoes are by a pupil of Taddeo Gaddi, Jacopo Landini da Casentino. The cross-vaulting in each bay is painted blue, with a starry design, upon which appear angels and virtues in Vesica-framing. The ribbing is beautiful, and the face of each arch is painted with quatre-foil designs and geometric settings.

Andrea Orcagna, Shrine, 1355–59 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The renowned and highly ornate Shrine itself is in the S.E. bay, and is encrusted with golden and blue vitreous tessarae and opus cosmatescum. A dome over the central portion rises between four pediments and four finials. An elaborate marble screen (in two tiers filled with wheel-like grilles) surrounds it, having cressets for lights along its cornice, and at the four angles twisted (tortellate) columns carrying angels with candles. It contains Ugolino’s sacred picture of the Madonna.

In the great plague of 1348 Florence suffered fearfully: citizens without number, pest-stricken themselves, after seeing their whole families die before them, bequeathed their all to the Company (which had been formed in honour of the Madonna of Orsanmichele) for distribution to the poor in honour of the Virgin; the offerings of gratitude, after the plague had ceased, were also considerable, and the total sum thus accumulated was found, on final computation to amount to more than three hundred thousand florins. The captains of the Company resolved to expend a portion of this treasure in erecting a tabernacle or shrine for the picture to which it had been offered, and which should exceed all others in magnificence. They entrusted the execution to Orcagna, who completed it in 1359, after ten years’ labour, having sculptured all the bas-reliefs and figures himself, while the mere architectural details and accessories were executed with equal care by subordinate artists, under his own eye and direction.

Orcagna, Tabernacle, 1359 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

And there it stands!—lost, indeed, in that chapel-like church, from which one longs to transport it to the choir of some vast cathedral—but fresh in virgin beauty after five centuries, the jewel of Italy, complete and perfect in every way—for it will reward the minutest examination. It stands isolated—the history of the Virgin is represented in nine bas-reliefs—two adorning each face of the basement, and the ninth, much larger, covering the back of the tabernacle, immediately behind the Madonna; one of the three Theological Virtues is interposed between each, couple of bas-reliefs, on the Western, Northern, and Southern faces respectively, the corresponding space at the East end, immediately below the large bas-relief, being occupied by a small door;—while, laterally, in the angles of each several pier that supports the roof, five small figures are sculptured, a Cardinal Virtue, in each instance, occupying the centre, attended, to the right and left, by a Virtue of sister significance and by two apostles, holding scrolls of prophecy or gospel—each series of five having reference apparently to the peculiar merits exemplified by the Virgin at the successive periods of her history, as commemorated in the bas-reliefs—the series of these

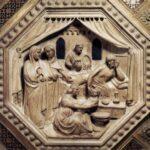

Orcagna, Birth of the Virgin, 1359 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

bas-reliefs beginning with her birth, on the North side of the basement, and running round from left to right. I may mention her Marriage and the Adoration of the Kings as peculiarly beautiful, and among the single figures those of Obedience, Justice, and Virginity.

The general adjustment and the commettitura, or placing of the different parts in this extraordinary shrine, is wonderful; Orcagna used no cement, but bound and knit the whole together with clamps of metal, and it has stood firm and solid as a rock ever since. In point of architecture, too, the design is exquisite, unrivalled in grace and proportion—it is a miracle of loveliness, and though clustered all over with pillars and pinnacles, inlaid with the richest marbles, lapis-lazuli, and mosaic-work, it is chaste in its luxuriance as an Arctic iceberg—worthy of her who was spotless among women. We cannot wonder, considering the labour and the value of the materials employed on this tabernacle, that it should have cost eighty-six thousand of the gold florins treasured up in the Orsanmichele or hesitate in agreeing with Vasari, that they could not have been better spent.

Lord Lindsay, Christian Art, vol. 1, pp. 375–78.

At the back is seen the rilievo by Orcagna (in which his own portrait occurs), representing Madonna giving her girdle to S. Thomas. It is signed and dated 1359. The wonderworking picture is enclosed. In front is a Madonna and infant adored by angels, perhaps by Bernardo Daddi.

A poem by Franco Sacchetti (1330–1400) celebrates the beauties of this tabernacle: —

Che passa di bellezza, s’io ben recolo,

Tutti gli altri che son dentro del secolo.

That exceeds in beauty, if I well recall,

All the others that are of the time.

Francesco da San Gallo, Virgin Child, and S. Anne, 1526 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The altar of S. Anna was erected by the Signoria as a thank-offering after the expulsion of the Duke of Athens in 1343. The statue of S. Anna holding the Virgin on her lap was executed by Francesco di San Gallo in 1526. On the opposite altar is Simone’s statue of the Virgin, which once stood in a niche of the Doctors, outside.

Over the altar on the right of the church is a rude wooden Crucifix carefully preserved, because when it was attached to a pillar of the Loggia, the good Bishop Antonino used to pray before it in his childhood. Before this crucifix also Savonarola used to be seen kneeling for hours.

Andrea della Robbia, Emblem of the Wool Guild (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

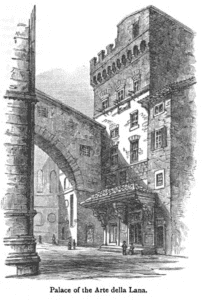

At the west end of the church, connected with it by an immense flying buttress (a sort of monstrous arm pretending to support it, which was made by Buontalenti, c. 1590, and ought to be knocked away), stands the grand old battlemented Torrione of the Arte della Lana (Guild of Wool), repeatedly adorned with its emblem, the Lamb bearing a banner. This was the most important of the old Guilds, and in the XVI c. it employed as many as 32,000 people. The house is now the presbytery of Or S. Michele. It was stormed by the Ciompi in 1378. The large hall has become the Sala di Dante. On the north of the church, opposite the statue of S. George, is the old residence of the Arte dei Beccai, or Guild of Butchers, afterwards of that of Builders, and on which the black he-goat rampant may still be seen, one of the finest heraldic street-signs in Florence, also the emblem of Borgo S. Apostoli. It is now occupied by the Congregazione di Carità.

Simone Talenti, San Carlo dei Lombardi, 1284 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

On the opposite side of the Via Calzaioli is the gothic church which the Signoria ordered Simone Talenti to finish, when an oratory of S. Anne was destroyed, for Or S. Michele. Lombard monks, who obtained it in 1616, changed its dedication to S. Carlo Borromeo. Here the Signoria, every September 29th, made their offering of new wine, and after it was blessed, drank to the prosperity of Florence. The altarpiece in it is by C. Rosselli.

Or San Michele would have been a world’s wonder had it stood alone, and not been companioned with such wondrous rivals that its own exceeding beauty scarce ever receives full justice.

Surely that square-set strength, as of a fortress, towering against the clouds, and catching the last light always on its fretted parapet, and everywhere embossed and enriched with foliage, and tracery, and figures of saints, and the shadows of vast arches, and the light of niches gold-starred and filled with divine forms, is a gift so perfect to the whole world, that, passing it, one should need say a prayer for the great Taddeo’s soul.

Surely, nowhere is the rugged, changeless, mountain force of hewn stone piled against the sky, and the luxuriant, dream-like, poetic delicacy of stone carven and shaped into leafage and loveliness, more perfectly blended and made one than where Or San Michele rises out of the dim, many-coloured, twisting streets, in its mass of ebon darkness and of silvery light.

The other day under the walls of it I stood, and looked at its Saint George, where he leans upon his shield, so calm, so young, with his bared head and his quiet eyes.

“That is our Donatello’s” said a Florentine beside me—a man of the people, who drove a horse for hire in the public ways, and who paused, cracking his whip to tell this tale to me. “Donatello did that, and it killed him. Do you not know? When he had done that Saint George he showed it to his master. And the master said, “It wants one thing only.” Now, this saying our Donatello took gravely to heart, chiefly of all because his master would never explain where the fault lay; and so much did it hurt him, that he fell ill of it, and came nigh to death. Then he called his master to him. “Dear and great one, do tell me before I die,” he said, “what is the one thing my statue lacks.” The master smiled, and said, “Only—speech.” “Then I die happy,” said our Donatello. And he—died—indeed, that hour.

Now, I cannot say that the pretty story is true; it is not in the least true; Donatello died when he was eighty-three, in the street of the Melon; and it was he himself who cried, “Speak, then speak!” to his statue, as it was carried through the city. But whether true or false the tale, this fact is surely true, that it is well—nobly and purely—well with a people, when the men amongst it who ply for hire on its public ways think caressingly of a sculptor dead five hundred years ago, and tell such a tale standing idly in the noonday sun, feeling the beauty and the pathos of it all.

“Our Donatello” still for the people of Florence—“Our own little Donatello” still, as though he were living and working in their midst today, here in the shadow of the Stocking-Makers’ street, where his Saint George keeps watch and ward.

Ouida, Pascarèl, vol. 2, pp. 185–188.

The northern part of the Via Calzaioli, from Via degli Speziali to the Duomo, was occupied by the palaces of the Adimari14Arms: Per Fess, or and azure. whom Dante flouts for cowardliness (Paradiso xvi.). Dante’s property was taken by Boccaccino degli Adimari.

An inscription at the corner of the Corso (R.) records the site of the Church of Santa Maria Nipoticosa, where S. Antonino used to preach from an outside pulpit. The site of the Loggia degli Adimari-Cavicciuli is also commemorated by an inscription; being a favourite lounging-place, it was known as “Neghittosa” (the Slothful).

On our left (by the Via degli Speziali) was the Mercato Vecchio of which Pucci wrote—

Mercato Vecchio al mondo è alimento

Ed ad ogni altra piazza il pregio serra;…

Le dignità di mercato son queste,

Ch’ ha quattro chiese ne’ suoi quattro canti

Ed ogni canto ha due vie manifeste.

The old market provides food for all the world,

And carries off the prize from every other piazza…

Such is the grandeur of this market

That it has four churches at the four corners,

And at every corner are two streets.

Antonio Pucci, La Proprietà di Mercato Vecchio, 9–11 (p. 268).

This most interesting part of Florence was destroyed by its ignorant and short-sighted Municipality in 1889.

The ancient quarter of the Mercato Vecchio, when cleaned, restored, and put in order, would have offered the faithful image of a mediaeval town, as Rome and Pompeii are samples of the Latin towns. Visitors could have walked in the old genuine Florentine city, in those very streets which Dante trod, in that city where the Guelf and Ghibelline factions fought against each other for centuries; the birthplace of many Florentines illustrious in science, letters, arms; where so many conspiracies were plotted, and where one may say, without exaggeration, that every wall, every stone, recorded a page of Florentine history.

“An Italian Architect,” “The Centre of Florence,” The Builder, vol. 56 (Feb. 23, 1889), p. 140.

The old market is in itself a gloomy square overlooked by lofty and almost uninhabitable buildings. The small shops in their basements are of the Seven-dials order—bird-shops alive with redpoles and linnets, greenfinches and nightingales, a sick pigeon or so, and shrieking parrots; also inevitable wine-shops, where language, equal to the rough stuff, is inspired, no doubt, by it; and then, the cook-shops, where brown fritters are hissing in bubbling oil and being turned; and fish-shops, with tubs containing salted haddock, and not containing it comfortably; fruiterers, evidently Hebrews, with lemons suspended on strings, together with rich piles of oranges, chestnuts and tomatoes, and crimson apples. Then follows a reach-me-down old-clothes den: and beyond it the noise of coppersmiths hammering up their pots and pans, but in the open are huge tattered umbrellas, beneath which sit old women and middle-aged selling their goods as at Verona and Brescia—certainly a peculiarly picturesque piece of Florence, and a place for Rembrandt.

Welbore St. Clair Baddeley.

Portions of three of the four churches of the Mercato—“the cradle of ancient Florence”—existed till 1890: of S. Maria in Campidoglio only the double flight of steps which once led to the entrance; S. Pietro Buonconsiglio had, over the entrance, a beautiful lunette by Luca della Robbia, and an outside pulpit; S. Tommaso tra le Torre was the parish church of the Medici, whose earlier palaces were in the Mercato. The fourth church was S. Andrea, attached to the oldest piazza, was a column, brought from the Baptistery, supporting a statue of Abundance, of the XV. c.

Giorgio Vasari, Loggia del Pesce, rebuilt 1956 in Piazza Ciompi (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The graceful and beautiful Loggia del Pesce was designed by Vasari for Cosimo I. All these interesting objects, for centuries the admiration of Europe, have been swept away to make a hideous square from which even Victor Emmanuel is evidently trying to escape. And indeed he did. The statue was moved to the Cascine in 1932.

This, which was the “Old Market” even in the eleventh century, was the oldest part of Florence, intersected by narrow alleys and full of quaint old houses. Even a cook-shop, five hundred years old, in the Mercato itself, had its interesting majolica decorations. In the Via dei Vecchietti was the place called Palazzo della Cavajola (of the Cabbage-woman) which belonged to the Guelfic Vecchietti.15Arms: Az., 5 ermines (2 and 2 confronting, and one), argent. Here Bernardo Vecchietto received Giovanni da Bologna, who made the quaint, charming bronze figure of the Devil, low down at the corner of the house, marking the site of a pulpit from which S. Pietro Martire exorcised the Evil One.16Formerly there were two of these Devils: one was stolen a few years ago; the other has been recently removed. The Piazza dei Vecchietti was surrounded by a number of old houses bearing noble shields with the arms of the families they belonged to. The simple habits of the Vecchietti (whose motto was “Candidior Animus” [a shining soul], produced one gonfalonier and twenty-six priori) are commemorated by Dante: —

E vidi quel de’ Nerli e quel del Vecchio

Esser contenti alla pelle scoverta,

E le sue donne al fuso e al pennecchio.

And him of Nerli saw, and him of Vecchio,

Contented with their simple suits of buff.

And with the spindle and the flax their dames.

Dante Paradiso 15:115–117. Trans. Longfellow.

Palazzo dei Catellini, formerly Castiglione, 14th c. (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The quarter south of the Mercato Vecchio was occupied by the Amieri,17Arms: Or, a bend azure, edged argent. whose chief Messer Foglia, decorated the walls of his houses with sculptured fig-leaves, in allusion to his name. These might till recently be traced on houses near the Church of S. Andrea. Close to this spot stood the beautiful Linaioli Tabernacle of Fra Angelico, now in the Museo di San Marco. Facing the site of the Piazza di S. Miniato tra Due Torre18The name bears witness to the former abundance of the towers, which were a necessity with the Florentine and Roman nobles. is the old palace of the Castiglione,19Arms: Gules, a lion, or, crowned. of whom was the giant-warrior Dante da Castiglione, celebrated for his share in the famous duel fought in 1529 in the presence of the Florentine and Imperialist armies. Other ancient palaces which have been destroyed, to make room for the discreditably commonplace erections which we now see, were those of the Anselmi, Della Luna, Elisei, Gondi, Migliorelli, Ugolini, Rigoli, Fiorini, Spigliati, Pescioni, Della Volta, Della Tosa, Brunelleschi, Tosinghi, Della Pressa, Medici, Nerli, Pecori, Filiteri da Castiglione, and Fighinelli, mostly decorated with the arms of those families.

The destroyed and rebuilt Via Pellicceria, or “Street of Furriers,” was once the Goldsmiths’ quarter, where the father of Baccio Bandinelli, instructed his son in the goldsmith’s art, and also had Benvenuto Cellini as a pupil. Here are still the Case dei Lamberti, a family20Arms: Az., 6 balls, or. illustrious in Florence from the tenth century, but which, being Ghibelline, disappeared under the domination of the Guelfs. Parts of the Lamberti palace afterwards belonged to the Arte degli Oliandoli (oil-merchants) and the Arte della Mercanzia (merchants’ guild). The massive, Neo-Renissance Palazzo delle Poste e Telegrafi (Via Pellicceria, 3) by architect Rodolfo Sabatini and engineer Vittorio Tognetti occupies an entire city block. Built between 1906-17 on land formerly part of the Mercato Vecchio that was cleared as part of an urban renewal project. The Via Calimala (Calle Mala, “Bad Street”?) was the quarter of the Guild of Wool-Merchants; to it belonged the Acciajuoli, Bardi, Cerchi, Peruzzi, and many other important families. At the corner of this street was a tabernacle containing an image of the Virgin, supposed to have arrested a great fire, inscribed: —

Ruppe, spezzò l’ orribil fuoco, fin qui volando,

Ma l’ Imagin pia pote troncarlo in questo loco.

The horrible fire, flying so far, broke, shattered

But the pious Image cut it off at this place.

Piazza della Republica (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Not only has all the interest of all this centre of Florence been remorselessly deleted since 1889, but the German-beer-drinking square—Piazza Vittorio Emanuele [renamed Piazza della Repubblica after WWII]—which has replaced it would be second-rate in Birmingham. In the excavations for making it, remains of a Roman temple and baths (also destroyed since) were discovered, with traces even of an Etruscan city, showing that an Etruscan town probably existed on the site of Florence, as well as on that of Fiesole, as folk believed in Dante’s time (But that malignant, thankless rabble/that came down from Fiesole long ago. Inferno 15:61–63). In the centre of the square, prancing over it all, was the equestrian statue of Victor Emmanuel II. by Emilio Zocchi.21Removed to the Casine. The steed, indeed, is in painful situation; for he is evidently not yet used to the band-stand beneath him, which he wishes to jump over; or does he perhaps desire to plunge with his immortal master into an abyss (like that of Curtius) which stubbornly refuses to open for him?

Returning to the Via Calzaioli, on the right (near the end), an inscription marks the house where the poet Salomone lived, and died in 1815. Another inscription records how a sycophant, Cerretieri Visdomini, to flatter the Duke of Athens, put his arms (a double-tailed lion rampant) over his house. This folly caused him to be torn to pieces by the people when the Duke was expelled (1343), but the arms remain, with their story beneath them.

Loggia del Bigallo (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

On the left, where the street falls into the Piazza del Duomo, is the exquisitely beautiful little gothic loggia called the Loggia del Bigallo, with a deep-shadowing cornice and roof, with great probability attributed to Andrea Orcagna, enclosed with iron gate by Francesco Petrucci da Siena, and an oratory. It dates from 1352.

The statuettes on either side the Virgin, on the façade, of S. Pietro Martire and S. Lucia, are by Filippo di Cristoforo, 1413.

The Madonna is interesting as the prototype of all future Madonnas of the Pisan school. In strict accordance with the spirit of early Christian art, which demanded the concealment of her figure, she is amply draped; and in token of her peculiar mission of showing Christ to the world, she holds Him far from her, as though her natural affections were absorbed in reverence for His divine nature.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, p. 14.

The upper chambers, or offices, of the Bigallo contain some interesting frescoes relating to the Temporal Works of Mercy. In the oratory is a beautiful predella, composed of what Vasari calls “superb miniatures” by R. Ghirlandajo, and a greatly revered image of the Virgin by Alberto Arnoldi, 1361.22From the 6th & 9th editions: “The Bigallo was terribly injured by ‘restorers’ in 1881–82.”

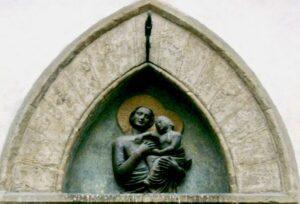

Alberto Arnoldi, Virgin and Child, 1361 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

It is the only known work of the artist. The Madonna is a dignified matron, rigid in attitude and impassive in countenance, enveloped in a once star-spangled drapery, of which the massive and carefully arranged folds fall over the lower half of the body of the Child, who sits poised upon her left arm. Although without beauty or expression, this group has a certain grandeur, from its impassiveness, like Egyptian statues, which seem immutable as fate, mocking at all approach to human sympathy.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, p. 71

The altar of gilded cypress is the work of Antonio “il Caroto.”

The Bigallo is intimately connected with the Confraternity of the Misericordia (called also Compagnia del Bigallo), on the other side of the Via Calzaioli, and the foundation of both had its origin in the piety of Pietro Borsi, who, in 1240, persuaded his young companions to agree that any one of them who used blasphemous language should pay a fine for the assistance of sick or wounded persons; from that time onward the “Brothers of Mercy” have existed in Florence. Today one sees ambulances parked in front of the Misericordia’s headquarters opposite the Duomo.

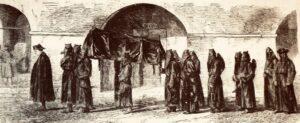

The Misericordia continues faithful to its work of six centuries. At a sound from the Campanile of the Cathedral, the Giornante, or dayworker, hastens to the residence in the Piazza, to learn his duties from the captain, or Capo di Guardia: a half-hour glass is turned to mark the interval between the summons and his arrival. Every Giornante is provided with his long black dress, and the hood which covers his face, only leaving holes for the eyes, so that he may not be recognised when upon his labour of mercy. The captain repeats the words, “Fratelli, prepariamoci a fare quest opera di misericordia” —“Brothers, let us prepare to perform this work of mercy;” and, kneeling down, he adds, “Mitte nobis, Domine, charitates, humilitates et fortitudines;” [Send us, O Lord, charity, humility and fortitude;] to which the rest reply, “Ut in hac opera te sequamur:” [to follow you in this work] after a prayer the captain exhorts the Brethren to repeat a Pater Noster and Ave Maria for the benefit of the sick and afflicted; then four of the number take the litter on their shoulders, and, preceded by their captain, the rest follow, bearing the burden in turns, and repeating every time when another set take it up, “Iddio le ne renda il merito” [God gives you merit] to which those who are relieved answer, “Vadano in pace”—“Go in peace.” When sent for by a sick person, the Brothers assist in dressing the patient, and carry him down to the litter, where he is gently and carefully laid. The Brethren sometimes act as sick-nurses, to which office they are trained; but they may never receive any remuneration, nor taste anything except a cup of cold water. As the Brothers of the Misericordia passed along the streets of Florence, all persons formerly raised their hats reverentially; but this custom has not been generally observed during the last few years.

The Misericordia continues faithful to its work of six centuries. At a sound from the Campanile of the Cathedral, the Giornante, or dayworker, hastens to the residence in the Piazza, to learn his duties from the captain, or Capo di Guardia: a half-hour glass is turned to mark the interval between the summons and his arrival. Every Giornante is provided with his long black dress, and the hood which covers his face, only leaving holes for the eyes, so that he may not be recognised when upon his labour of mercy. The captain repeats the words, “Fratelli, prepariamoci a fare quest opera di misericordia” —“Brothers, let us prepare to perform this work of mercy;” and, kneeling down, he adds, “Mitte nobis, Domine, charitates, humilitates et fortitudines;” [Send us, O Lord, charity, humility and fortitude;] to which the rest reply, “Ut in hac opera te sequamur:” [to follow you in this work] after a prayer the captain exhorts the Brethren to repeat a Pater Noster and Ave Maria for the benefit of the sick and afflicted; then four of the number take the litter on their shoulders, and, preceded by their captain, the rest follow, bearing the burden in turns, and repeating every time when another set take it up, “Iddio le ne renda il merito” [God gives you merit] to which those who are relieved answer, “Vadano in pace”—“Go in peace.” When sent for by a sick person, the Brothers assist in dressing the patient, and carry him down to the litter, where he is gently and carefully laid. The Brethren sometimes act as sick-nurses, to which office they are trained; but they may never receive any remuneration, nor taste anything except a cup of cold water. As the Brothers of the Misericordia passed along the streets of Florence, all persons formerly raised their hats reverentially; but this custom has not been generally observed during the last few years.

Susan & Joanna Horner, Walks in Florence, vol. 1, pp. 96–97.

The Grand-Duke wore the black robe and hood, as a member of the Compagnia della Misericordia, which brotherhood includes all ranks of men. If an accident takes place, their office is to raise the sufferer, and bear him tenderly to the hospital. If a fire breaks out, it is one of their functions to repair to the spot and render their assistance and protection. It is also among their commonest offices to attend and console the sick; and they neither receive money, nor eat, nor drink, in any house they visit for this purpose. Those who are on duty for the time are called together, at a moment’s notice, by the tolling of the great bell of the tower; and it is said that the Grand Duke might be seen, at this sound, to rise from his seat at table and quietly withdraw to attend the summons.

Charles Dickens, Pictures from Italy, pp. 266–67.

Ducarme, lithograph after Francesco Pieraccini, Costume of the brothers of the Misericordia who transport the sick

While these brothers, “black-stoled, black-hooded, like a dream,” continue to light the way to dusty death with their flaring torches through the streets of Florence, the mediaeval tradition remains unbroken, Italy is still Italy. They knew better how to treat Death in the Middle Ages than we do now. These simple old Florentines, with their street wars, their pestilences, their manifold destructive violences, felt instinctively that he, the inexorable, was not to be hidden or palliated, not to be softened or prettified, or anyways made the best of, but was to be confessed in all his terrible gloom; and in this they found, not comfort, not alleviation, but the anæsthesis of a freezing horror. Those masked and trailing sable figures, sweeping through the wide and narrow ways by night to the wild, long rhythm of their chaunt, in the red light of their streaming torches, and bearing the heavily draped bier in their midst, supremely awe the spectator, whose heart falters within him in the presence of that which alone is certain to be.

W. D. Howells, Tuscan Cities, pp. 112–13.

Torre degli Adimari (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

A few doors beyond the Bigallo is the little Piazza Adimari, where occur the shields of the Misericordia belonging to it, and of Acciajuoli impaling Minerbetti.

We are now at the ritual centre of Florentine interest, in the Square of the Cathedral (1296).