4.2: San Lorenzo & Medici-Riccardi Palace

The Borgo di S. Lorenzo, which opens northward opposite the Arcivescovado, leads speedily to the Piazza S. Lorenzo, in one corner of which is a statue of Giovanni delle Bande Nere (father of Cosimo I.) by Baccio Bandinelli. The pedestal has a relief representing Giovanni receiving his prisoners of war. Like most of the works of a conceited but indifferent master, the statue has been much ridiculed, and was thus apostrophised by the rhymesters of his time:

Sir Giovanni delle Bande Nere,

Dismounted from a long, boring, tiring ride,

and sat down.1Messer Giovanni delle Bande Nere, / Dal lungo cavalcar noiato e stanco, / Scese di cavallo e si pose a sedere.

The famous condottiere, Giovanni delle Bande Nere (son of Giovanni de’ Medici by his marriage with the famous Caterina Sforza, widow of Girolamo Riario), died in his twenty-ninth year, the day after having his leg amputated for a wound he received before Borgoforte. During the operation he refused to be bound, and himself with unflinching hand held the torch which lighted the operators.

At a neighbouring bookstall Browning picked up the “old yellow book” whence he derived the substance of The Ring and the Book.

Gave a lira for it, eightpence English just (1865).

………………………………………………….

Toward Baccio’s marble, ay, the basement ledge

O’ the pedestal where sits and menaces

John of the Black Bands with the upright spear,

Twixt palace and the church—Riccardi, where they lived,

His race, and San Lorenzo, where they lie.

Robert Browning, The Ring and the Book

San Lorenzo (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The rough-faced Church of S. Lorenzo was originally due to the munificence of a Christian matron, Giuliana, who vowed to erect a church in honour of S. Laurence if she should give birth to a son. The basilica she built was consecrated when that son was twelve years of age, in A.D. 393, by S. Ambrose, and called the Basilica Ambrosiana, and here Bishop Zenobio lay buried for eleven years, A.D. 429–440, before his translation to S. Salvador.2The curious story of the foundation of S. Lorenzo by Giuliana is told by S. Ambrose in his “Exhortation to Virginity.” It was injured by fire in 1423, during a service.

In 1435 Brunelleschi was appointed to overlook the rebuilding of S. Lorenzo, but he only lived to see the Sagrestia Vecchia completed—the rest was altered and completed by Antonio Manetti. The result is certainly disappointing, and it is largely due to the quite unnecessary entablature carrying the arches, which stilts the columnar effect into weakness.

San Lorenzo nave (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

San Lorenzo is 260 feet in length by 82 in width, with transepts 171 feet from side to side. No church can be freer from bad taste than this one; and there is no false construction, nor anything to offend the most fastidious. Where it fails is in the want of sufficient solidity and mass in the supporting pillars and the pier-arches, with reference to the load they have to bear; and a subsequent attenuation and poverty most fatal to architectural effect.

James Fergusson, History…Modern Styles of Architecture, p. 41.

It consists within of eight bays, having rounded arches and side chapels with a frescoed cupola over the crossing. The vaulting is flat, and panelled out in gilt and stucco.

It was here that Savonarola preached many of his most striking sermons, even against the Medici, who were patrons of the church. Here Alessandro de’ Medici was married to Margaret (of Parma), daughter of Charles V., and here, by order of Cosimo I., the splendid funeral service of Michelangelo took place on June 28, 1564, when Varchi pronounced the funeral oration.

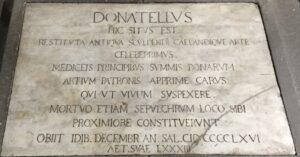

In front of the choir a porphyry slab covers the remains of Cosimo de’ Medici—Cosimo il Vecchio, Pater Patriae—who died August 1464. Donatello also lies there with his illustrious patron.

Cosimo Tomb Marker (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

On the porphyry pavement covering the funeral vault, the modest epitaph was engraved, which can still be seen there today, and remarkable for these two words: Pater Patriae. It was the title which, thirty years previously, popular enthusiasm had awarded him on the day of his triumph, and which on the day of his funeral a public decree had again consecrated, ordering that it be inscribed on his tomb. Such a beautiful title should have sufficed for the glory of Cosimo. Perhaps it would never have been disputed to him whether, for the dignity of their name and above all in the interest of the State, his descendants had always followed the examples given by their illustrious ancestor.

Alphonse Dantier, L’Italie, vol. 2, p. 96.

He left to posterity the fame of a great and generous patron, the infamy of a cynical, self-seeking, bourgeois tyrant.

J. A. Symonds, Sketches and Studies in Italy, p. 141.

Near the tomb of Cosimo repose the bones of his son Piero; of Lorenzo the Magnificent; of Giovanni di Pierfrancesco, who was the grandfather of Cosimo I.; of Lorenzo di Giovanni, brother of Cosimo; and of Cardinal Ippolito. A simple marble stone, on which their name is cut, alone marks the place where they rest in their eternal sleep.

Luigi Passerini.

In the N. aisle is a fanciful monument by Thorwaldsen to Pietro Benvenuti, the painter of the cupola in the mausoleum.

The terminal chapel (of the Sacrament) of the N. transept has a rich altar by Desiderio da Settignano,3The sketches which Desiderio made for this work are in the Uffizi. called by Giovanni Santi, “II bravo Desider, si dolce e bello.” [the good Desiderio, yes sweet and beautiful] It was the “Gesù Bambino” above this altar which was carried through the streets by an army of children, who, at the instigation of Savonarola (Feb. 7, 1497), called for every work of art of an immoral tendency, that it might be destroyed by fire in the Piazza S. Marco. In the next chapel lie the bones of Cennini, the earliest Florentine printer. The bronze pulpits are very late works of Donatello, finished by his pupil Bertoldo.

The church became the burial-place of many great Florentine families. The Martelli, Stufa, Rondéinelli, Ughi, Gattani, Marucelli, Cini, Aldobrandini, Ginori, Ubaldini, Neri, Cambini, and others, have vaults under the church.

In the 1st chapel of the left transept are three cabinets containing the relics given to the church by Clement VII., with others which were formerly in the chapel of the Pitti Palace. The 2nd chapel, that of the Martelli, contains a charming Annunciation by Filippo Lippi, and a realistic crucifix by Benvenuto Cellini. To this chapel a very graceful tomb, in the form of a cradle, by Donatello, has been brought from the crypt. A modern monument (1896) to Donatello is by Raffaello Romanelli.

At the entrance of the southern aisle is a fresco of the martyrdom of S. Laurence by Bronzino. Over the door leading to the cloister is a marble singing gallery by Verocchio, and in the next chapel is a S. Sebastian by Jacopo da Empoli.

In the south transept is the square Sagrestia Vecchia by Brunelleschi, adorned with Corinthian pilasters, having reliefs of the Evangelists and statuettes by Donatello. In the centre of the pavement is a sarcophagus, also by Donatello, erected by Cosimo Vecchio to his parents, Giovanni and Piccarda de’ Medici. The sacristy also contains the porphyry monument of Giovanni and Piero—il Gottoso (the Gouty), sons of Cosimo de’ Medici, erected by Giuliano and Lorenzo the Magnificent, the sons of Piero. It is the work of Andrea Verocchio. On the wall is a profile of Cosimo “Pater Patriae,” who built this sacristy. The picture of S. Lorenzo, with SS. Stephen and Leonard, is by Albertinelli.

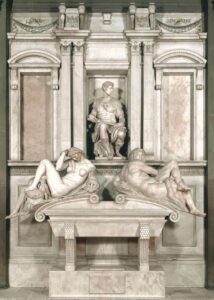

Michelangelo, Tomb of Giuliano de’Medici (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Michelangelo, Tomb of Lorenzo de’Medici (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The Sagrestia Nuova is on the north side of the church, and has an external entrance. It was designed by Michelangelo,4The original design is often attributed to Giovanni de’ Medici, the gifted natural son of Cosimo I. by Eleanora degli Albizzi. who was ordered by Clement VII. (Giulio de’ Medici) to construct it, instead of continuing the magnificent façade for the church, which had been ordered by his predecessor Leo X. (Giovanni de’ Medici). It was begun in 1523, and occupied Michelangelo for twelve years. Here are the monuments of Lorenzo, Duke of Urbino, grandson of Lorenzo the Magnificent, and father of Catherine de’ Medici, who died in 1519, and of his uncle Giuliano, Duke de Nemours, third son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, who was early weary of life, and composed a sonnet in defence of suicide. He died, probably of poison, aged thirty-seven, March 1516.5His widow was the charming Philibert de Savoie, the friend of Marguerite de Valois, and the “Anima Eletta” [Chosen soul] of Ariosto, who herself died in 1524, aged twenty-six.

The melancholy statue of Lorenzo is called “Il Pensoso”—“the thinker.” The narrow niches in which the Medici are confined would make it impossible for them to stand upright, and the disproportionate figures below are slipping off the pitiable pedestals which support them, giving an acute sense of discomfort to the beholder.

The figures beneath Lorenzo are intended for Twilight and Dawn. Dawn, wearily awaking, is perhaps the finest of the four statues.

Night (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Below the statue of Giuliano are Night andDay—Day a mere bozzetto.6It is singular how few either of the statues or pictures of Michelangelo are finished. They resemble Leonardo’s pictures. Many people, though they used not to dare confess so much, will find it difficult to understand the praises which generations have heaped upon these statues,7It was quite uncertain which of the two Medici each statue was intended for, till February 24, 1875, when the tombs were opened, and two bodies, evidently those of Lorenzo and his son Alessandro il Moro, were found beneath that which bears the statues of Twilight and Dawn. and, indeed, on many other extraordinary, but charmless productions.

Four ineffable types, not of darkness nor of day—not of morning nor evening, but of the departure and the resurrection, the twilight and the dawn, of the souls of men.

John Ruskin, Modern Painters, vol. 2, p. 116.

The head of the famous Day was probably left unfinished because Michelangelo perceived that it was turned beyond the limit permitted to nature without breaking the neck.

W. W. Story, Conversations in a Studio, p. 164.

The Day and Night in the Medici Chapel have something terrible in their solemnity. They are all wrong, if you please, full of defects, impossible, unnatural, but they are grand thoughts and mighty in their character, and they overawe you into silence. I would counsel no artist to attempt to copy them or form his style upon them; let him rather absorb them as impressions than study them as models.

W. W. Story, Conversations in a Studio, p. 165.

It is of the figure of Night that Giovanni Battista Strozzi wrote: —

Carved by an Angel, in this marble white

Sweetly reposing, see the Goddess Night,

Calmly she sleepeth—so must living be;

Waken her gently; she will speak to thee. 8La Notte che tu vedi in sì dolci atti / Dormir, fu da un Angelo scolpita / In questo sasso, e perché dorme, ha vita: / Destala, se nol credi, e parleratti.

To which Michelangelo replied: —

Grateful is sleep, whilst shame and wrong survive

More grateful still in senseless stone to live;

Gladly both sight and hearing I forego;

Oh, then awake me not! Hush! —whisper low.9Grato m’ è ‘l sonno, e più l’ esser di sasso, / Mentre che il danno e la vergogna dura; / Non veder, non sentir, m’ è gran ventura: / Perô non mi destar, deh! parla basso!

Translations by J. C. Wright.

Michel’s Night and Day

And Dawn and Twilight wait in marble scorn,

Like dogs upon a dunghill, couched on clay

From whence the Medicean stamp’s outworn,

The final putting-off of all such sway

By all such hands, and freeing of the unborn

In Florence and the great world outside Florence.

Three hundred years his patient statues wait

In that small chapel of the dim St. Laurence:

Day’s eyes are breaking bold and passionate

Over his shoulder, and will flash abhorrence

On darkness, and with level looks meet fate,

When once loose from that marble film of theirs;

The Night has wild dreams in her sleep, the Dawn

Is haggard as the sleepless, Twilight wears

A sort of horror; as the veil withdrawn

‘Twixt the Artist’s soul and works had left them heirs

Of speechless thoughts which would not quail nor fawn,

Of angers and contempts, of hope and love:

For not without a meaning did he place

The princely Urbino on the seat above

With everlasting shadow on his face,

While the slow dawns and twilights disapprove

The ashes of his long-extinguished race

Which never more shall clog the feet of men.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Casa Guidi Windows, Part 1:3.

Is not thine hour come to wake, O slumbering Night?

Hath not the Dawn a message in thine ear?

Though thou be stone and sleep, yet shalt thou hear

When the word falls from heaven—Let there be light!

Thou knowest we would not do thee the despite

To wake thee while the old sorrow and shame were near.

We spake not aloud for thy sake, and for fear

Lest thou shouldst lose the rest that was thy right,

The blessing given thee that was thine alone,

The happiness to sleep and to be stone:

Nay, we kept silence of thee for thy sake

Albeit we knew thee alive, and left with thee

The great good gift to feel not nor to see;

But will not yet thine Angel bid thee wake.

Algernon Charles Swinburne, In San Lorenzo.

The Day and Night in the Medici Chapel have something terrible in their solemnity. They are all wrong, if you please, full of defects, impossible, unnatural, but they are grand thoughts and mighty in their character, and they overawe you into silence. I would counsel no artist to attempt to copy them or form his style upon them; let him rather absorb them as impressions than study them as models.

W. W. Story, Conversations in a Studio, p. 165.

Perhaps of all the statues that of Lorenzo, “Il Pensieroso,” has been the most admired: —

Michelangelo, Lorenzo de’Medici (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The statue that sits above the allegories of Morning and Evening is like no other that ever came from a sculptor’s hand. It is the one work worthy of Michelangelo’s reputation, and grand enough to vindicate for him all the genius the world gave him credit for. And yet it seems a simple thing enough to think of or to execute; merely a sitting figure, the face partly overshadowed by a helmet, one hand supporting the chin, the other resting on the thigh. But after looking at it a little while, the spectator ceases to think of it as a marble statue; it comes to life, and you see that the princely figure is brooding over some great design, which, when he has arranged in his own mind, the world will be fain to execute for him. No such grandeur and majesty have elsewhere been put into human shape.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, Passages from the French and Italian Note-Books, vol. 2, pp. 50–51.

Nor then forget that Chamber of the Dead,

Where the gigantic shapes of Night and Day,

Turned into stone, rest everlastingly;

Yet still are breathing, and shed round at noon

A twofold influence—only to be felt—

A light, a darkness, mingling each with each;

Both, and yet neither. There, from age to age,

Two ghosts are sitting on their sepulchres.

That is the Duke Lorenzo. Mark him well.

He meditates, his head upon his hand.

What from beneath his helm-like bonnet scowls?

Is it a face, or but an eyeless skull?

‘Tis lost in shade; yet, like the basilisk,

It fascinates, and is intolerable.

His mien is noble, most majestical!

Then most so when the distant choir is heard

At morn or eve nor fail thou to attend

On that thrice-hallowed day, when all are there;

When all, propitiating with solemn songs, Visit the Dead.

Then wilt thou feel his Power.

Samuel Rogers, Italy: A Poem, pp. 104–05.

Michelangelo, Virgin and Christ Child (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Opposite the altar is a Madonna and Child, also by Michelangelo—a mere sketch in marble. On one side of it is S. Cosmo by Montorsoli; on the other, S. Damiano by Montelupo.

The stairs of the Sagrestia Nuova lead also to the Medicean Chapel (Cappella dei Principi) (admission as at the Sagrestia Nuova), built as a Mausoleum by the Grand-Duke Ferdinand I., younger son of Cosimo I. It was begun in 1604, and is entirely covered with precious marbles and pietra-dura work. The armorial bearings of the principal cities of Tuscany are introduced as decorations. The granite cenotaphs of the Medici stand around. The only ones which have statues are those of Ferdinand I. (ob. 1608), by Giovanni da Bologna, and Cosimo II. (ob. 1620), by Pietro Tacca.

The chapel de’ Depositi is a work of Michelangelo, and the first he ever built; but the design is petty and capricious. The chapel of the Medici is more noble and more chaste in the design itself; though its architect was a prince, and its walls were destined to receive the richest crust of ornament that ever was lavished on so large a surface.

Joseph Forsyth, Remarks on Antiquities, Arts, and Letters, pp. 89–90.

In 1791 Ferdinand III. gathered together all the coffins containing the royal bodies, and had them piled together pell-mell in the subterranean vaults of the chapel, caring scarcely to distinguish one from another; and there they remained uncared for, and protected from invasion only by two wooden doors, with common keys, till 1857. But shame then came over those who had the custody of the place, and it was determined to put them in place and order. In 1818 a rumour was current that the Medicean coffins had been violated and robbed of all the articles of value which they contained; but it was not till thirty-nine years afterwards, in 1857, that an examination into the fact was made. It was then found that the rumour had been well founded. The forty-nine coffins containing the remains of the family were taken down one by one, and a sad state of things was exposed. Some of them had been broken into and robbed, some of them were the hiding-places of rats and every kind of vermin; and such was the nauseous odour they gave forth, that at least one of the persons employed in taking them down lost his life by inhaling it. In many of them nothing remained but fragments of bones and a handful of dust; but where they had not been stolen, the splendid dresses, covered with jewels, the wrought silks and satins of gold embroidery, the helmets and swords, crusted with gems and gold, still survived the dust and bones that had worn them in their splendid pageants and ephemeral days of power; and in many cases, where everything that bore the impress of life had gone, the hair still remained, almost as fresh as ever. Some, however, had been embalmed, and were in fair preservation; and some were in a dreadful state of putrefaction. Ghastly and grinning skulls were there, adorned with crowns of gold. Dark and parchment-dried faces were seen, with thin golden hair, rich as ever, and twisted with gems and pearls and golden nets. The cardinals still wore their mitres and red cloaks and splendid rings. On the breast of Cardinal Carlos (son of Ferdinand I.) was a beautiful cross of white enamel, with the effigy of Christ in black, and surrounded with emeralds, and on his hand a rich sapphire ring. On that of Cardinal Leopold, the son of Cosimo II., over the purple pianeta was a cross of amethysts, and on his finger a jacinth set in enamel. The dried bones of Vittoria della Rovere Montefeltro were draped in a dress of black silk of beautiful texture, trimmed with black and white lace, with a great golden medal on her breast, and the portrait of her as she was in life lying on one side, and her emblems on the other; while all that remained of herself was a few bones. Anna Luisa, the Electress Palatine of the Rhine, daughter of Cosimo III., lay there, almost a skeleton, robed in a rich violet velvet, with the electoral crown surmounting a black, ghastly face of parchment—a medal of gold, with her name and effigy, on one side, and on her breast a crucifix of silver; while Francesco Maria, her uncle, lay beside her, a mass of putrid robes and rags. Cosimo I. and Cosimo II. had been stripped by profane hands of all their jewels and insignia; and so had been Eleonora de Toledo and Maria Christina, and many others, to the number of twenty. The two bodies which were found in the best preservation were those of the Grand-Duchess Giovanna d’Austria, the wife of Francisco I., and their daughter Anna. Corruption had scarcely touched them, and they lay there fresh in colour as if they had just died. The mother, in her red satin, trimmed with lace, her red silk stockings and high-heeled shoes, the earrings hanging from her ears, and her blonde hair as fresh as ever; and equally well preserved was the body of the daughter. And so, centuries after they had been laid there, the truth became evident of the rumour that ran through Florence at the time of their death, that they had died of poison. The arsenic which had taken from them their life had preserved their bodies. Giovanni delle Bande Nere was also there—the bones scattered and loose within his iron armour, and his rusted helmet with the vizor down.

W. W. Story, Excursions in Art and Letters, pp. 45–48.

San Gallo, Paolo Giovio (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

In the cloister, which was designed by Brunelleschi, close to the entrance from the church, is the monument, by San Gallo, of Paolo Giovio, the historian, a native of Como, ob. 1552. He is represented in his robes as Bishop of Nocera. A door near this leads to the crypt, where Donatello and Benedetto and Giuliano da Majano are buried near Cosimo il Vecchio. The cloister is, by ancient custom, the refuge of all homeless cats; any one wishing to dispose of a cat brings it here and abandons it, with the knowledge that it will be provided for. The feeding of the cats, which takes place when the clock strikes twelve, is a curious sight. Broken meat and scraps of bread, &c., collected at house-doors, are brought in a sack, and from every roof and arch and parapet wall, mewing, hissing, and screaming, the cats rush down to devour it. In this cloister of a church so much connected with Michelangelo, we may note the kind of window-grating bulging out below, so common in Florence, called Kneeling Windows.

Michelangelo, Laurentian Library

The cloister is overlooked by the windows of the Laurentian Library, built by Michelangelo (1524) for Clement VII. to receive the Medicean collection, which was begun by Cosimo I., and augmented by his son Piero and his nephew Lorenzo the Magnificent. It was dispersed at the sack of the Medici palaces in 1494, but what survived was sold to Savonarola and formed the nucleus of the library at S. Marco. The more valuable books were taken, in 1508, to Rome (by Leo X.), but restored to Florence after his death by Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici (Clement VII.), when they were brought here.

Vasari, Stairs to Laurentian Library (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

A beautiful double staircase added by Vasari leads to the library. Its windows are filled with stained glass, displaying the shields of Cosimo I. and Clement VII., by Giovanni da Udine. The red and white inlaid pavement, by Tribolo, is of great rarity and beauty. The ranges of presses are filled with precious illuminated MSS. The library contains more than 7000 MSS., including original letters of Petrarch, his Horace and Cicero; many precious illuminated Missals, including the magnificent fifteenth-century choir-books of the cathedral, brought from S. Reparata, to which they were given by the Arte della Lana; also the famous copy of the Pandects of Justinian, captured by a Pisan fleet in 1137 at Amalfi, and .given by Leo X. to the Duke of Urbino, but restored in 1786. Some of the illuminations are by the Giottesque Oderisi whom Dante extols as “the honour of the art.” [Purgatorio 11:79–80.] Cellini’s autobiography in his own hand; a ninth-century Tacitus.

The more precious MSS., in the inner rooms, can be seen only by special permission of the direttore. The earlier of these come from the convent of the Angeli in the Via Alfani, and are many of them of the XIII. c.; the later, from the Duomo, are mostly XIV. and XV. c. The Log-book of Pierino Visconti, 1327. Some exquisite illuminations are by Lorenzo Monaco; others by Jean Fouquet. An Irish missal of the XI. c. is of great interest. Others have pictures important as representing Florence in early times; in a picture of the Miracle of S. Zenobio the old cathedral of S. Reparata is seen. In the Evangelista Siriaca, a MS. of the VI. c., is one of the earliest pictorial representations of the Crucifixion and Resurrection. A precious case inlaid with jewels is that which contained the documents relating to the Council of Florence. The Biblia Amiatina, brought from the monastery of Amiata, was written by Ceolfridus, a monk of the English Wearmouth. (690–716), and taken by him to Rome as an offering at the sepulchre of S. Peter. Music MSS. of Florentine composers, with miniatures, given to Lorenzo by Squarcialupi, the organist.

The designs of many of the illuminations of the XIII. and XIV. c. make it evident how much they were influenced by the art of the jewellers.

A precious little volume of the Offices of the Madonna, with nine marvellous pictures, was executed by Lorenzo de’ Medici. A volume on architecture has MS. notes by Leonardo da Vinci.

The reading-room is a Rotunda.

Giuseppi Mengoni, Mercato Centrale, 1874 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

A little behind S. Lorenzo is the modern Mercato Centrale, built by Giuseppi Mengoni in 1874. From the Via S. Antonino, which skirts one side of the market, opens the Via del Amorino, named from a romance of Machiavelli. Here No. 13, called the Casa dei Cartelloni, was the house of the astronomer Vincenzo Viviani(d. 1702), a favourite pupil of Galileo, to whom the latter bequeathed his library, and whose bust is over the door.

In the Via de’ Ginori, which contains the Piazza S. Lorenzo, is (right, No. 11) the Palazzo Ginori, where the sculptor Bandinelli died in 1559. It contains some good pictures. The family of Ginori,10Ginori Arms: Az. on a bend or, 3 stars of the first, on a canton a fleur-de-lis in chief. which came from Calenzano at the beginning of the XIV. c., has produced many famous generals, ambassadors, and statesmen. One of its members, the senator Carlo, founded the great Doccia china manufactory in 1740. At No. 15 is the Casa Taddeo, where an inscription records the visit of Raffaelle to one of the family in 1505. In No. 17, Palazzo Garzoni) is a good picture by Albertinelli. An inscription on No. 16 records that it was the house of the sculptor Luigi Pampaloni, who died there in 1847.

The corner of the Via de’ Ginori and Via Guelfa is known as the Canto alle Macine, from a millstone commemorating an ancient mill which existed here when the Mugnone ran through the Via de’ Ginori; from this stone the Jesuit Lainez, the friend of Loyola, used to preach.

The Via de’ Ginori falls into the Via di S. Gallo.

One Sunday, Giotti, being on his way to S. Gallo, and having stopped in the Via del Cocomero to tell some story, was so rudely caught by a pig running down the street, that he fell. He rose, however, very quietly, and, smiling, turned to the person nearest him, saying, “The brute is right. Have I not in my day earned thousands with the help of his bristles, and never given one of them even a cup of broth?”

Franco Sacchetti, [slightly different trans. By Mary Steedmann, Tales of Sacchetti LXXV]

No. 10 Via S. Gallo is the Palazzo Castelli, built by Gherardo Silvani in 1634, and adjoining it is the house where Benedetto da Majano was born in 1452. At the corner of Via 27 Aprile the Church of S. Apollonia, founded 1339, has a door by Michelangelo, whose niece lived in the convent. The convent is now a most interesting little Museum of the works of the rare master, Andrea del Castagno.

This is the best place for studying the works of this remarkable painter, who, the son of a peasant, showed his chief power in the delineation of the lusty limbs and sinews which were characteristic of those amongst whom he was brought up.

The convent contains: 1st Hall: —

School of Pollajuolo. An interesting figure of Justice from the old offices of the Sale e Tabacci.

Two fine works of the School of Ghirlandajo, from the ancient Badia di Settimo, one representing S. Gregory the Great and S. Joseph kneeling by a Pietà; the other the Adoration of the Magi.

Neri dei Bicci. The Virgin adoring the Infant Christ, with S. Joseph in humble adoration behind. The careful botany of this picture is interesting: behind the Holy Child grows the giglio of Florence.

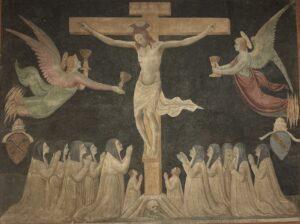

Neri dei Bicci. The Crucifixion, with angels catching the blood. From the Convent of the Murate.

The 2nd Hall is the Chapter-House of the convent, for which Andrea del Castagno painted his deeply interesting Cenacolo, with the Crucifixion, Entombment, and Resurrection above it. The figures in the Last Supper are characteristic of the crude powers of the painter, but the head of S. Andrew is fine; that of S. Thomas a remarkable example of foreshortening. Round the room (brought hither in 1891 from the Bargello but currently in the Uffizi) are the frescoes removed from the Villa Pandolfini, now Passerini, at Legnaia, and transferred to canvas. In the room for which they were painted (1435), the half-length figure of Esther, “the deliverer of her country,” occupied a central position over a door. On either side were the figures of sybils. Beyond these, on the left, were fancy portraits of the three poets, Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio; on the right, Farinata degli Uberti (the best piece), with Niccolò Acciajuoli and Pippo Spano, the patron of Masolino.

At the corner of the Via degli Arazzieri the church of S. Jacopo dei Preti has a fine painted ceiling; restored 1893. It contains the grave of a Florentine wit, the parish priest Arlotto, 1484, inscribed—

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Curabitur erat felis, dictum et elementum sed, ultrices vitae arcu. Morbi quis facilisis dui, id finibus urna. Proin id nisl gravida, semper metus venenatis, euismod neque. Praesent nisi ante, posuere ac enim quis, sodales scelerisque orci. Sed finibus luctus ligula at dictum. Donec viverra nunc vitae viverra suscipit. Sed hendrerit elit ac nunc aliquam, vitae rutrum ex lacinia. Nulla facilisi. Donec vel velit blandit, varius odio vitae, aliquam odio. Aliquam finibus fringilla dolor, id convallis est mollis non. Duis sit amet sodales magna, iaculis porttitor magna. Cras vel eros neque. Aenean sodales ligula id placerat posuere. Vestibulum a tempor libero.

Italian Hours, p. 186.

Questa sepoltura il Piovano

Arlotto fece fare

Per sè e per chi ci vuol entrare.

The pious, vain [pio+vano] Arlotto

Had this sepulchre made

For himself and those who want to enter.

No. 64 was the house of Baccio d’Agnolo; in No. 45 Santi di Tito died in 1603. In the Via delle Ruote (left) is the church of S. Maria Assunta dei Battilani (of the wool-combers), where the Ciompi (badge on jambs) held their meetings in 1378, under Michele di Lando, whose portrait is preserved here (keys at 20 I piano [1stfloor]).

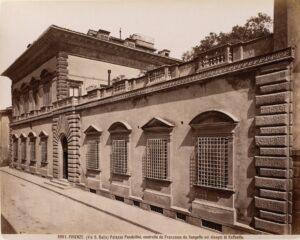

Photograph by Giacomo Brogi (attrib.), Palazzo Pandolfini, 1520, design by Raphael, c. 1856-81 (photo via National Gallery of Canada)

The church of S. Giovannino de’ Cavalieri (1321), in the Via S. Gallo, belonged to the nuns of S. John of Jerusalem. No. 74 is the Palazzo Pandolfini, designed by Raffaelle (1520) for Gianozzo Pandolfini, Bishop of Troia (whose tomb by Mino is in the Badia), of a family which has produced twenty-eight priori, twelve gonfalonieri, and many famous warriors, cardinals, and bishops.11Arms of Pandolfini: Per fesse arg. az.; in chief (R) a vase or, with 3 flowers; in base, 3 dolphins or, and above (L) beneath a label of 4, gules, 3 fleurs-de-lis, or. The church of S. Agata, attached to the military hospital, has paintings by Allori. Arms over door, of Pucci, the builder of the façade, a moor’s head, with a fillet.

In Piazza della Libertà beyond the Porta di San Gallo, which was built 1284–1337, and took its name from a church (and has on its inner side a lunette by the son of Ghirlandajo), is a Triumphal Arch (1738), erected in honour of the entry of Francis II., husband of Maria Teresa—“an arch in the most perfect opposition to the grave and austere architecture of the city which it announces.”12Joseph Forsyth, Remarks on Antiquities, Arts, and Letters, p. 92. The open meadow beyond is said to have been the property of Dante. This used to be to the Florentines what the Cascine are now. Smollett, writing of this spot in 1765, says: —

Here, in summer evenings, the quality resort to take the air in their coaches. Every carriage stops, and forms a little separate conversazione. The ladies sit within, and the cicisbei [gallants] stand on the footboards, on eacside of the coach, entertaining them with their discourse.

Tobias Smollett, “Letter 27,” Travels Through France and Italy, vol. 2, p. 54.

Michelozzo, Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, 1430 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

A street on the right leads to La Madonna della Tosse, built by the Duchess Cristina in 1596 to enshrine a miraculous statue of the Madonna, supposed to cure coughs. The porch was added in 1640, and restored 1857. To the left is the Ponte Rosso.

At one corner of the Piazza S. Lorenzo stands the magnificent and typical Palazzo Medici-Riccardi (1430), [formerly the Prefettura], begun in 1430 by Cosimo Vecchio before his exile, from the designs of Michelozzo (1396–1472). Here, when Cosimo was being carried through the palace in his old age after the death of his favourite son Giovanni, the unhappy father was heard to murmur, “Too large a house for so small a family.” Here, under his son Piero il Gottoso [the Gouty], the enthusiasm for learning, first animated by Cosimo, continued to have its centre. Marsilio Ficino, who remained at the court, burnt a lamp before the bust of Plato, as before an altar; and Sacchetti relates how a passer-by, unreproved, took the candles which burnt before a crucifix, and placed them before the bust of Dante, saying, “Take them, for thou art the more worthy.”

Michelozzo , Palazzo Medici-Riccardi corner, 1445–1460 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The upper storeys of the palace, overshadowed by a far-projecting cornice, have plain surfaces which gain by contrast with the grand basement-storey of rough-hewn stones. They have biforate round-headed windows, and dentil stringcourses. Rings for torches and banners are attached to the windows, and at one corner is a beautiful fanale [wrought iron lantern] by Niccolò Caparra. Here was born, January 1, 1449, the great Lorenzo. This was the palace where the earlier Medici held their court, and though Cosimo I. removed his residence to the Palazzo Vecchio, it remained in the hands of the Medici till sold by Ferdinando II. to the Marchese Gabriele Riccardi in 1659. Here Charles VIII. (1494) of France, Pope Leo. X., and the Emperor Charles V. were royally lodged. Here also Duke Alessandro, illegitimate brother of Catherine de’ Medici and the last male lineal descendant of Cosimo Pater Patriae, was murdered (1537) by his cousin Lorenzino, who had been the minister of his pleasures.

On the way up to the chamber to which the dwarfish, sickly little tyrannicide has lured his prey, the most dramatic moment occurs. He stops the bold ruffian whom he has got to do him the pleasure of a certain unspecified homicide, in requital of the good turn by which he once saved his life, and whispered to him, “It is the Duke!” Scoronconcolo, who had merely counted on an everyday murder, falters in dismay. But he recovers himself: “Here we are: go ahead, if it were the devil himself!” And after that he has no more compunction in the affair than if it were the butchery of a simple citizen. The Duke is lying there on the bed in the dark, and Lorenzino bends over him with, “Are you asleep, sir?” and drives his sword, shortened to half-length, through him; but the Duke springs up, and crying out, “I did not expect this of thee!” makes a fight for his life that tasks the full strength of the assassin, and covers the chamber with blood. When the work is done, Lorenzino draws the curtains round the bed again, and pins a Latin verse to them, explaining that he did it for the love of country and the thirst for glory.

W. D. Howells. Tuscan Cities, pp. 81–82.

The room where this crime was committed was pulled down afterwards, and has been kept in ruins ever since. Though sold to the Riccardi13Arms of Riccardi: Azure, a key palewise, argent, the catch turned to right, above. by Ferdinand II. in 1659, the palace was repurchased in 1814 by the Grand Duke, and is now public property.

The Riccardi Palace, notwithstanding its early date (1430), illustrates all the best characteristics of the style. It possesses a splendid façade, 300 feet in length by 90 in height. The lower storey, which is considerably higher than the other two, is also bolder, and pierced with only a few openings, and these placed unsymmetrically, as if in proud contempt of those structural exigencies which must govern all frailer constructions.

James Fergusson, History…Modern Styles of Architecture, p. 83.

The court of the palace is surrounded by many of the sarcophagi which once stood outside the Baptistery, some of them exceedingly interesting. The great Gallery is painted with the Apotheosis of the Medici by Luca Giordano (1632–1705). — “Luca fa presto;”[Luca is quick] Cosimo III., his uncle Cardinal Leopoldo, and other members of the family, appear as divinities. It was here that Charles VIII. of France received the deputies of the Republic to discuss the terms of the treaty he proposed with the city; and here, when the King, impatient of delays, threatened to sound his trumpets, he received the famous answer of Pietro Capponi — “Blow your trumpets, we will ring our bells” —and the answer saved Florence.

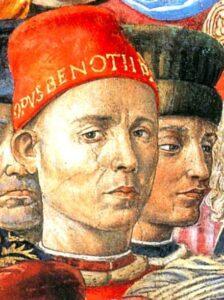

But the gem of the palace is the Chapel. It is entirely covered by beautiful frescoes of Benozzo Gozzoli (1400–1478), said to have been painted by lamplight (1459), as there was originally no window to the chapel. The altar-piece, removed to make the present window, must have represented the Virgin and Child, to whom the angels on either side the choir are kneeling in adoration or standing and singing praises. The rest of the walls is occupied by the procession of the Magi, winding through a rocky country—except at the angles, where the shepherds are represented leaving their flocks. The details of beasts, birds, and flowers are most beautiful. One small portion of the fresco, where a secret staircase existed, is a later addition. In the foreground on the right is Cosimo Pater Patriae. The three kings are, as usual, portrayed of different ages, and the models are said to have been the Patriarch of Constantinople, John Palæologos, Emperor of the East, and (on a white horse) Lorenzo il Magnifico. The artist is also introduced, with “Opus Benotii” [Benotti’s Work] upon his cap.

Behind the adoring angel groups, the landscape is governed by the most absolute symmetry; roses and pomegranates, their leaves drawn to the last rib and vein, twine themselves in fair and perfect order about delicate trellises: broad stone pines and tall cypresses overshadow them, bright birds hover here and there in the serene sky, and groups of angels, hand joined with hand, and wing with wing, glide and float through the glades of the unentangled forest. But behind the human figures, behind the pomp and turbulence of the kingly procession descending from the distant hills, the spirit of the landscape is changed. Serener mountains rise in the distance, ruder prominences and less flowery vary the nearer ground, and gloomy shadows remain unbroken beneath the forest branches.

John Ruskin, Modern Painters, vol. 2, pp. 188–89.

Serried ranks of seraphs, peacock-plumed, and kneeling in prayer; garlands of roses everywhere; contemporary Florentines on horseback, riding in the train of the three Magi kings under the low boughs of trees; and birds fluttering through the dim, mellow atmosphere; the whole dense and close in an opulent yet delicate fancifulness of design.

W. D. Howells, Tuscan Cities, pp. 77–78.

Up these dull, slow stairs what famous men and women have passed! Into this dim rainbow of a chapel how many times Lorenzo and Giuliano remembered, and forgot their crimes! What absolving music has been chanted! What pledges vainly sworn! See what magnificence and beauty still live on the walls, what silent faces rejoice! Those noble chargers tread upon flowers; that is why you cannot hear them as they go! Those hounds hunt upon the distant hills! Those angels with peacock-eyed pinions stand for ever and sing in the green gardens of Paradise perhaps you can just hear them? In all Florence there is scarcely a fairer sight than this!

St. C. B. [St. Clair Baddeley]

The Bibliotéca Riccardiana was collected by the Marchese Vincenzo Capponi: it is open to the public. And in the Codex of the Canzoni is a portrait of Dante (1436).

Bartolommeo Ammanati, San Giovannino degli Scolopi, 1581 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Palazzo Martelli (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Close to this palace is the Church of S. Giovannino degli Scolopi, rebuilt for the Jesuits by Bartolommeo Ammanati (1581), who gave his whole patrimony towards the work. He was buried here with his wife, the poetess Laura Battifera. They are both represented in the altar-piece of Christ and the woman of Cana, which was painted for them by Alessandro Allori. The body of the murdered Duke Alessandro was concealed in this church in 1536. The observatory was founded by Ximenes. The schools adjoining are those of the Liceo Galileo. In the neighbouring Via Zannetti, No. 8, is the Palazzo Martelli,14Arms: Gules, a winged and langued griffin rampant, or. since 2009 Museo di Casa Martelli, a civic museum, that once contained a beautiful statue of S. John Baptist by Donatello, which he presented as a token of gratitude to his early patron, Roberto Martelli.15For a full discussion see H. W. Janson, Donatello, pp. 191–96. The statue was sold in 1912 and is now in the Museo Nazionale (Bargello). Also in the Bargello is Donatello’s coat of arms that he created for the Martelli that the State purchased in 1998 thereby resolving the matter of the Bandini inheritance. The civic museum contains interesting ceiling frescos and works by Domenico Beccafumi, Salvator Rosa, and a collection of boxwood sculptures, 1743–51, after the antique by Johannes Sporer.] On the opposite house is a relief of the Madonna by Mino da Fiesole. A tablet on No. 2 records that it was the residence of the poetess Maddalena Morelli (crowned on the Capitol as Corilla Olympica). Mozart lived in the same house (Mar. 30, 1770), and here struck up his warm friendship with Thomas Linley (drowned 1778).