4.4: Accademia, Chiostro dello Scalzo, SS. Annunziata, Museo Archeologico, via dei Servi

At the S. corner of the Via Ricasoli1Formerly Via del Cocomero, re-named from the patriot Bettino Ricasoli, who was born at No. 9 in 1808. and the Piazza S. Marco is the ancient Ospedale di S. Matteo, now the Accademia delle Belle Arti.

[Editor’s note: With few exceptions, the paintings listed in the various prior editions of Florence have been removed. Most are now in the Uffizi. Those works no longer in the Accademia, but included in the 6th and 9theditions, have been reassigned in this edition according to their present (2022) location. In the 9th edition St. Clair Baddeley writes: “There are two rooms besides which are being prepared for other additions to this Gallery, which, since the war [WWI], has contributed a large quota of its masterpieces of the XV. and XVI. centuries to the new systematic scheme adopted so wisely in the Uffizi and Pitti Galleries (which King Victor Emanuel has now presented to the town and people of Florence), not to speak of several works of Beato Angelico which it has contributed to swell the collection of his works in San Marco.”]

In the little hall which was the original entrance are four admirable reliefs by Luca della Robbia. In the present entrance are some lovely works of the Della Robbia, and the bozzetto of a Statue of S. Matthew by Michelangelo.

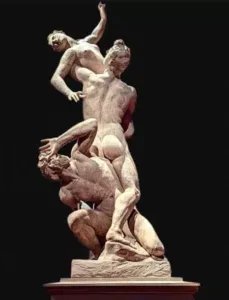

Giambologna, Rape of the Sabines (plaster model), 1582 (photo Galleria Accademia)

Alesso Baldovinetti, The Trinity and Saints Benedict and Giovanni Gualberto, 1472

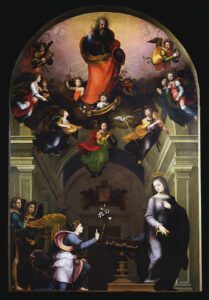

Giovanni Antonio Sogliani, Immaculate Conception

Dispute, 1530

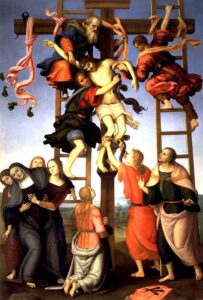

Filippino Lippi and Pietro Perugino, Descent from the Cross, 1504–07

Pietro Perugino, Assumption of the Virgin with Four Saints, 1500

Botticelli, Madonna and Child, Baptist, and Two Angels, 1468

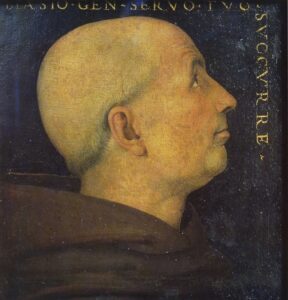

Pietro Perugino, Don Biagio Milanesi, 1500

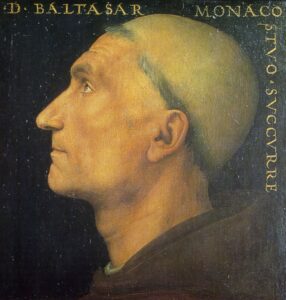

Pietro Perugino, Don Baldassarre di Angelo, 1500

Room 3: Galleria dei Prigioni (Gallery of the Slaves/Prisoners)

The corridor [the Galleria] leads at once to the Tribune.2The 9th edition of Florence notes that the Corridor then contained “a magnificent series of sixteen Brussels tapestries which were purchased by Eleonora da Toledo in 1552 for 5,500 scudi d’oro. They depict the stories of Adam and Eve, Noah, and Joseph.” p. 162.

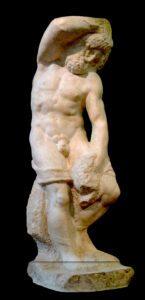

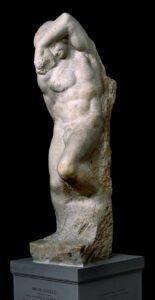

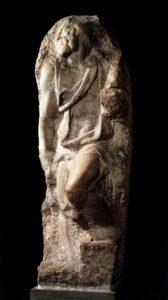

There are beside statues more or less imperfect of some prisoners designed to have adorned the mighty tomb of Julius the Second (1518) in Rome. There is also a torso of a river-god and plaster-casts of the Moses in S. Pietro, in Vincoli, and the Pietà, in S. Peters.

Michelangelo, Bearded Slave, 1530 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Michelangelo, Young Slave, 1530 (photo Galleria Accademia)

Michelangelo, Awakening Slave, 1530 (photo Galleria Accademia)

Michelangelo, Atlas, 1525-30 (photo Galleria Accademia)

Michelangelo, S. Matthew, 1505-06 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Michelangelo, Palestrina Pietà, 1550-60 (photo via Galleria Accademia)

Here, also, and of especial interest, is seen the unfinished statue by Michelangelo of S. Matthew intended once for the Duomo.

The statue of S. Matthew looks like the antediluvian fossil of a human being of an epoch when humanity was mightier and more majestic than now, long ago imprisoned in stone and half uncovered again.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, Passages from the French and Italian Note-Books, vol. 2, pp. 112–13.

On the Corridor walls are a number of paintings including:

Room 4: The Tribune

The Tribune was opened April 1882.3Built by Emilio de Fabris, who also designed the western façade of the Duomo. Hither (owing to damage from rain), the famous Statue of David (1504) by Michelangelo—“Il Gigante”—has been removed from its original and far better situation at the gate of the Palazzo Vecchio, a position which was of the greatest interest, as having been chosen by Michelangelo himself at a council composed of all the great contemporary painters and sculptors.

Michelangelo’s sculpture is not generally made to have a roof over it. The exaggeration of the muscles, which is its defect, becomes a merit in those positions where the light absorbs and devours everything.

Jules Michelet. Histoire de France, vol. 9, p. 665 (note #26).

Having selected David as his subject, Michelangelo made a sketch, in which the shepherd hero stood with his foot upon the head of Goliath, but the shape of the marble not admitting of such action, he designed the wax model now in the Casa Buonarroti, according to which he sculptured the statue as we now see it. The marble was set up on end, and enclosed so that the sculptor need not be interfered with in his work, which was far advanced in the month of February 1503, and ready to be given up to the Signory, who had purchased it from the merchants of the Woollen Guild, within a year after that date. Though trammelled in a way especially irksome to an artist so free in expression of thought, Michelangelo showed in this statue no other sign of the conditions under which he worked, save in the meagreness of its forms, which we soon forget in our admiration for the grandeur and bold modelling of the figure, its ease of attitude, and the collected, watchful expression of the face. Giant himself, David is a match for any Goliath; too much so, perhaps, as a representation of the youth who, strong only in the grace of God, went out with a sling in his hand, to do battle against the champion of the Philistines.

As soon as the statue was set upon its pedestal the Gonfaloniere Pier Soderini came to see it, and after expressing his great admiration for the work, suggested that the nose seemed to him too large; hearing this, Michelangelo gravely mounted on a ladder, and after pretending to work for a few moments, during which he constantly let fall some of the marble dust he had taken up in his pocket, turned, with a questioning and doubtless a slightly sarcastic expression in his face, to the critic, who responded, “Bravo! bravo! you have given it life.”

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 2, pp. 17–19.

On the whole, it has suffered very little. Weather has slightly worn away the extremities of the left foot; and in 1527, during a popular tumult, the left arm was broken by a huge stone cast by the assailants of the palace. Giorgio Vasari tells us how, together with his friend Cecchino Salviati, he collected the scattered pieces, and brought them to the house of Michelangelo Salviati, the father of Cecchino. They were subsequently put together by the care of the Grand Duke Cosimo, and restored to the statue in the year 1543.

J. A. Symonds, Life of Michelangelo, vol. 1, p. 97.

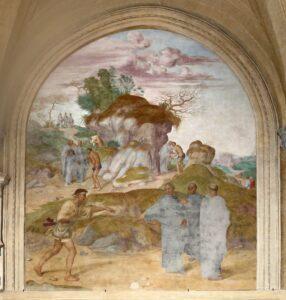

Chiostro dello Scalzo (No. 69 Via Cavour) belonged to the gardens of Ottaviano de’ Medici, where the Scalzi, or barefooted Recolletan friars, had a court, for the decorations of which they employed Andrea del Sarto and his friend Franciabigio, who lived with him. The subject chosen was the life of John the Baptist. The execution of the frescoes occupied them from 1517 to 1526. They are, beginning from the right: —

1. Faith

2. The Announcement to Zacharias.

*3. The Meeting of Mary and Elizabeth.

*4. The Birth of John.

5. The Benediction of Zacharias.

6. The Meeting of John and Jesus.

7. The Baptism of Christ.

8. Love—with most Lovely children—are

Represented.

9. Justice

10. The Preaching of the Baptist.

11. The Baptizing of John’s Disciples.

12. John a Prisoner before Herod.

*13. The Dance of Herodias’ Daughter (Salome)

*14. The Beheading of the Baptist

15. The Bringing of the Head to Herod

16. Hope

All these are by Andrea del Sarto, except 5 and 6, which are by Franciabigio, and 7, which (as well as the frieze) is the united work of the two friends. They are all executed in chiaroscuro.4In his pictures, Andrea del Sarto constantly painted his wife, Lucrezia de Fede, of a noble family which gave six Priors to Florence.

In these mural designs there is such exultation and exuberance of young power, of fresh passion and imagination, that only by the innate grace can one recognise the hand of the master whom we know but by the works of his later life, when the gift of grace had survived the gift of invention. Here, what life and fulness of growing and strengthening genius, what joyous sense of its growth and the fair field before it, what dramatic delight in character and action! where S. John preaches in the wilderness; and the few first listeners are gathered together at his feet, old people and poor, soul-stricken, silent—women, with worn, still faces, and a spirit in their tired aged eyes that feeds heartily and hungrily on his words—all the haggard funereal group filled from the fountain of his faith with gradual fire and white heat of soul; or where Salome dances before Herod, an incarnate figure of music, grave and graceful, light and glad, the song of a bird made flesh, with perfect poise of her sweet light body from the maiden face to the melodious feet; no tyrannous or treacherous goddess of deadly beauty, but a simple virgin, with the cold charm of girlhood and the simple charm of childhood; as indifferent and innocent when she stands before Herodias and when she receives the severed head of John with her slender and steady hands; a pure bright animal, knowing nothing of man, and of life nothing but instinct and motion. In her mother’s mature and conscious beauty there is visible the voluptuous will of a harlot and a queen; but, for herself, she has neither malice nor pity; her beauty is a maiden force of nature, capable of bloodshed without blood-guiltiness; the king hangs upon the music of her movement, the rhythm of leaping life in her fair fleet limbs, as one who listens to a tune, subdued by the rapture of the sound, absorbed by the purity of passion, I know not where the subject has been touched with such fine and keen imagination as here.

Algernon Charles Swinburne, Essays and Studies, pp. 352–54.

“There is a little man in Florence,” said Michelangelo to Raffaelle of Andrea del Sarto, “who, if he were employed on such great works as you are, would bring the sweat to your brow.”

[Francesco?] Bocchi.

Buontalenti, Casino Mediceo, portone (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Near this (No. 63), in the Via Cavour, is the Casino Mediceo, adorned by Buontalenti in 1570 for Francesco I. It was in the gardens of this palace that Lorenzo the Magnificent used to collect all the literary celebrities of his time, and to its galleries that he invited all the young students of art to study from his antiquarian collections. The villa was sacked after the banishment of Piero de’ Medici, but restored as an academy in 1512. After the death of Francesco I. and Bianca Cappello their son Antonio resided here. Under the later Grand Dukes it was a barrack of the noble guard, and was used for public offices including, until 2012, the Court of Appeal with busts of the Grand Duchesses Maddalena of Austria and Vittoria della Rovere. In the rooms once inhabited by Prince Antonio, formerly the Court of Assizes, are frescoes portraying the history of the first four Grand Dukes. Opposite is the Farmacia di S. Marco.

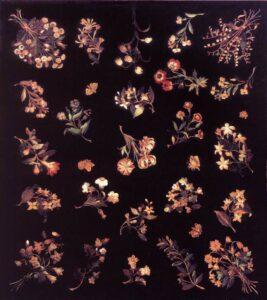

Continuing south on via Cavour one turns right (east) onto via degli Alfani where the Museo dell’Opificio delle Pietre Dure is located at No. 78. Ferdinando I. founded the Opficio in 1588 to produce mosaics. Opened in 1882 and updated in 1995, the museum traces the history of Florentine mosaic work through three centuries. A notable examples of pietra dure (hard stone) work is Francesco Ferrucci’s Portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici. Jacopo Ligozzi’s design for a table top, which includes flowers and insects arranged on a black ground, typifies much of the Opificio’s work. In the 18th c. the painter Giuseppe Zocchi collaborated with the workshop which made mosaic copies of his vedute (scenic views) of Florence.

Piazza SS. Annunziata (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

From the Accademia, a few steps (E.) bring us to the Piazza della SS. Annunziata (Servi di Maria), surrounded by arcades and decorated with busts of the Medicean Grand Dukes. It is adorned by an equestrian statue of Ferdinand I. (younger son of Cosimo I., first Cardinal, then Grand Duke) by Giovanni da Bologna (made from cannon taken from the Turks by Knights of S. Stephen) and two bronze fountains by Pietro Tacca. The central door on the left leads to the Foundling Hospital—Spedale degli Innocenti—founded in 1421, and designed by Filippo Brunelleschi. The medallions are by Andrea della Robbia. It contains several good pictures, especially: —

Andrea della Robbia, Annunciation c. 1493 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Filippo Lippo. The Infant Jesus brought to the Madonna by an angel.

Over the door of the chapel is an Annunciation by Andrea della Robbia.

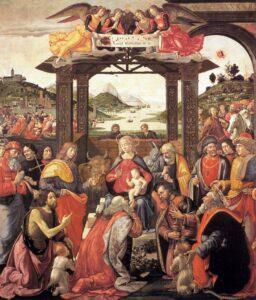

The type of the Virgin is always the same family portrait, a prosaic portrait which the artist [Domenico Ghirlandajo] has not even thought of embellishing. Besides, he has so much poetry poured out, as it were, on all his accessory parts, that the most systematic severity remains disarmed. In the background, the artist has introduced a heartbreaking scene of the Massacre of the Innocents: Mothers who, wanting to rescue their children from death by fleeing, find themselves and them trapped between a river and the iron executioners. By contrast, this river—which extends as far as the eye can see—beautiful mountain ridges, and an admirable, transparent pure sky, deliciously rest the soul. This painting is dated 1488, the time when the author, having realized his own strength, said to his brother David that, now that he was beginning to be initiated into the secrets of his art, he regretted that he had not been given the entire circumference of the city walls to cover with historical paintings.

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, vol. 1 (1861), pp. 386–87.

Over the door of the chapel is an Annunciation by Andrea della Robbia.

The Church of the SS. Annunziata was built by the Order of Servites—Servi di Maria—which was founded at Florence by seven noble Florentines, who used to meet daily to sing Ave Maria in the chapel of S. Zenobio, where the tower of Giotto now stands. It was originally built in 1250, but has been modernised, and is now the fashionable church of Florence, with the best music, and the only one open all day.5The Miserere is sung here between 5.30 and 7 o’clock on Ash Wednesday, Holy Thursday, and Good Friday. It is approached by a portico of seven arches by Antonio San Gallo and Ceccini, containing a lunette in mosaic of the Annunciation, by Dom. Ghirlandajo. Door to left leads to the cloisters. This leads into a courtyard surrounded by precious frescoes now enclosed with glass. Beginning from the right, they represent:

Baldinucci relates that when Jacopo da Empoli was copying this picture (#4) in 1570, an old lady stopped on her way to mass and talked to him. She showed him one of the figures in the fresco as the likeness of Andrea’s wife, and then disclosed that she herself was Lucrezia del Fede, the widow of the hatter, Carlo Recanati, in the Via S. Gallo, whom Andrea had married, to the great discomfort of his pupils, and who had so often served as his model.

SS. Annunziata Nave

The interior of the Annunziata, in form a Latin cross with apsidal choir, used to be filled (like the still unaltered church of S. Maria delle Grazie near Mantua) with waxen images of eminent living as well as dead persons, here suspended from the ceiling. On one side were the citizens,6The image of Lorenzo de’ Medici, by Verocchio, was in the dress in which he escaped assassination by the Pazzi; that of Giuliano was by Montelupo; that of Alessandro (which fell down three days before his murder) by Benvenuto Cellini. on the other popes and foreign potentates—even a Turkish Pasha. Vasari writes that after the Pazzi conspiracy, which left Giuliano dead and his brother Lorenzo the Magnificent wounded,

it was ordained by the friends and relations of Lorenzo that many figures of him should be made and set up in various places, by way of thanksgiving to God for his safety. Then Orsino, among others, with the help of Andrea [Verrocchio], made three figures in wax, of the size of life, forming the skeleton in wood, as we have before described, and completing it with split reeds. This frame-work was then covered with waxed cloth, folded and arranged with so much beauty and elegance that nothing better or more true to nature could be seen. The head, hands, and feet were afterwards formed in wax; of greater thickness, but hollow within; the features were copied from the life, and the whole was painted in oil with such ornaments and additions of the hair and other things as were required, all which being entirely natural and perfectly well done, no longer appeared to be figures of wax;, but living men, as may be seen in each of the three here alluded to….The second figure of Lorenzo is attired in the lucco, which is a dress peculiar to the Florentine citizens, and this is in the church of the Servites, the Nunziata, namely: it stands over the smaller door where the wax; lights are sold.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 2, pp. 253–54.

Bernardo Rossellino, Tomb of Orlando di Guccio de’ Medici, 1450s (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Beginning on the right—

In the 1st Chapel is: —

Jacopo da Empoli. The Virgin with saints (much restored).

In the 2nd Chapel:

Tomb of Marchese Luigi Tempi-Marzi-Medici, by U. Cambi (1849).

In the 5th Chapel:

The simple and beautiful XV. c. Tomb of Orlando de’ Medici by Simone di Betto, brother of Donatello. His last descendant, Carlotta de’ Medici, was buried near him in 1859.

In the 6th Chapel:

The grave of Stradano the painter (1536–1605). Bust by his son Scipione.

In the Right Transept:

Bacci Bandinelli, Pietà from his own tomb monument (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The Tomb of Bacci Bandinelli, being a Pietà from his own hand. The figure of Nicodemus is supposed to be a portrait of the artist, who is buried here with his father and wife.

Outside the Tribune:

Francesco da Sangallo, Monument to Angelo Marzi, 1546 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Tomb of the Senator Donato dell’ Antella, who became a Servile late in life, ob. 1666, by Gio. Batt. Foggini; and that of Angiolo Marzi-Medici, Bishop of Arezzo, ob. 1546, by F. di San Gallo.

The Tribune has a circular dome, painted by Il Volterrano, beneath which is the isolated choir, where the stalls and a ciborio are by Baccio d Agnolo. In the Cappella del Soccorso, behind the high-altar, is the tomb of Giovanni da Bologna, from his own design. The bas-reliefs are by his pupils, Tacca and Francavilla. The next tribune chapel has a picture of the Resurrection by Ang. Bronzino. In the principal chapel of the left transept are the tombs of the historians Giovanni, Matteo, and Filippo Villani (1275–1364).

1st Chapel (descending left of the nave):

Perugino. The Assumption. (Manni?)

2nd Chapel:

Stradano. The Crucifixion. The best work of the artist

Michelozzo, Shrine of the Madonna (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Last Chapel (left of entrance) (of the Annunciation, built from designs of Michelozzo, by Piero de’ Medici), has a gorgeous little shrine in front of it, with silver altar and hanging lamps.

Pietro Cavallini. The Annunciation, supposed to have been finished by angelic hands.

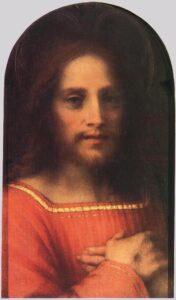

The crucifix here is by Giuliano di S. Gallo, the figure of the Infant Jesus by Baccio Bandinelli. The head of Christ over the altar is by Andrea del Sarto.

Carlo Dolci, Desiderio da Settignano, and Andrea del Sarto lie in this church.

In this church, S. Luigi Gonzaga, at ten years old, took the vows of chastity.

The large Cloister—dei Morti—attributed to Simone Pollajuolo and Michelozzo, is surrounded with frescoes by Poccetti.

Over the door leading into the church is the charming and celebrated fresco of *Andrea del Sarto, called La Madonna del Sacco, 1525.

For drawing, grace, and beauty of colour, for liveliness and relief, no artist has ever done the like.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Foster, vol. 3, p. 221.7Hare has edited Foster’s text.

Michelangelo so highly thought of this work that he said to Raffaelle of its author, “ti farà sudar la fronte.” [it will make your brow sweat]

One of the greatest benefactors of the convent—il chiarissimo Falconieri—is buried beneath the fresco.

Cappella dei Pittori (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Opening into the cloister is the Cappella dei Pittori, where the Company of Painters (founded 1350) or Guild of S. Luke, used to hold their meetings. Over the altar are some small pictures by Fra Angelico. Jacopo Pontormo, Franciabigio, Benvenuto Cellini, and Lorenzo Bartolini are buried here. Montorsoli built the chapel at his own expense as a resting-place for them. The vestibule contains some second-rate works.

Behind the Annunziata runs the Via Gino Capponi, formerly Via S. Sebastiano, which contains a beautiful piece of Luca della Robbia over a door leading to a cloister which belonged to S. Piero Maggiore. Here, at the corner of the Via del Mandorlo, No. 24, is the house of Andrea del Sarto, and where he died wanting food; afterwards inhabited by Fed. Zuccaro.

About the centre of the street (No. 28) is the Palazzo Capponi, built (1705) after a design by Fontana, where the illustrious statesman, Gino Capponi, died in 1876. The satirical poet Giusti also died here. The palace contains a few good pictures. The Capponi family,8Arms: Per bend, sable-argent. who came from Lucca in the XIII. c., has given ten gonfalonieri and fifty-six priori to the state. Its most celebrated members were Neri (d. 1457), who defeated the Duke of Milan at Anghiari, and his nephew Piero, whose boldness saved Florence from Charles VIII. of France: he was killed at the siege of Sojana in 1496. The nearly opposite Palazzo Velluti Zati (formerly San Clemente) was inhabited by Prince Charles Edward, who died here in 1788. No. 50 is the Palazzo Ruspoli, with beautiful gardens.

Guido Parigi, Palazzo della Crocetta, 1620,now

Museo Archeologico

Giulio Parigi, Palazzo della Crocetta, 1620 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

On a line with the front of the Annunziata is the Via della Colonna, containing, in the Palazzo della Crocetta (formerly a Medici Palace, No. 26), the Museo Archeologico. The Museo Etrusco (occupying the ground floor and great part of the first floor) is of the greatest interest, especially to those who have visited the remarkable sites where its treasures were found. Those little interested in antiquities will be struck by the great variety and beauty of the pottery, especially of the black vases of (bucchero) South Etruria; the furniture considered necessary for the tombs—candlesticks, bottles for ointment, small dinner services, all very curious. The small bronzes from Telamone are of wonderful beauty. Many interesting things come from the excavations in the Mercato Vecchio. Four objects deserve especial attention:—

Minerva d’Arezzo (detail), c. 400 B.C. (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

L’Arringatore (Orator), 110–90 B.C. (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Chimera of Arezzo, c. 400 B.C. (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Idolino, c. 30 B.C. (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

A Chimera (part lion, goat, and serpent) of 300 to 400 B.C., found at Arezzo in 1554. The inscription on the left leg shows its dedication to the god Tin.

An exquisitely wrought bronze situla or bucket, found at Bolsena in 1871, with relief, Dionysos returning to Olympus.

Seven rooms of the first floor are occupied by the Egyptian Museum, a magnificent collection brought hither from S. Onofrio. A room on the left contains the Collection of Greek and Roman Bronzes, including the famous Idolino9In the 9th edition of Florence, the Idolino was dated c. 450 B.C. A note states: “By some artist of the Polycleitan circle. The motive is thought to be that of pouring a libation. This statue is a Greek original: probably the figure is that of a divinity.” Current scholarship regards the Idolino as an early Roman empire, pseudo-Polycleitan sculpture. found at Pesaro in 1530, and brought to Florence by Vittoria della Rovere on her marriage with Ferdinando II.

Room I. represents the Terramare culture, with hut urns and furniture from the cemeteries of Vctulonia. In Room II. will be found jewellery from tombs of the vii.-vm. c. b.c., and the well-known bronze casket inlaid with silver plaques bearing mystic symbols. Volterra and Populonia are represented richly in Rooms IV.-VII. ; Orvieto (Volsinii) and Cortona in IX. and XI. The Etrurian towns and strongholds nearer Rome will be found recalled in XIV. and XVIII. ; Chiusi (or Clusimn), in Room VIII., in which are several ivth c. b.c. Greek (imported) objects from a tomb at Montepulciano. Fiesole has contributed things both Etruscan and Roman to Room XXIII. and in its neighbour and in XXI. will be seen relics of Roman ‘ Florentia/ especially from the neighbourhood of its Forum (Piazza Savoia or Mercato Vecchio), and the Gambrinus Halle of to-day.

The Egyptian Museum occupies the staircase and 7 rooms on the first floor, of which latter Room I. is devoted to the Gods and Goddesses, Room II. to Inscriptions and Sculpture, Room III. contains Mummies, Room VI. much domestic furniture, toilet articles and basketry, while in Room VII. is a beautiful wooden chariot dating from Rameses II.

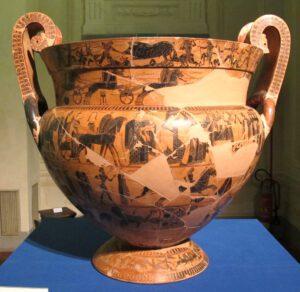

François Vase, c. 570 B.C. (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

François Vase, c. 570 B.C. (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The subjects of the vase the following are in order: Face A:

1st zone: Caledonian wild boar hunt: Peleus contends with Meleager for the first place in the hunt.

2nd zone: Funeral games in honor of Patroclus: Olyteus (Ulysses), Automedon, Diomedes, Damasipos and Hipothoon compete for the prizes of the race (lebeti and tripods) proposed by Achilles.

3rd zone: Epitalamic (nuptial) procession: Zeus and Hera, Poseidon and Amphitrite in a quadriga accompanied by Muses and preceded by the Hours, Dionysos, Hestia, Chariklo and Demeter, Iris and Chiron, with wedding gifts; they are received by Peleus in front of the thalamus of Thetis (Thetideion).

4th zone: Achilles’ first enterprise below Troy: Ambush at the fountain of the Trojans and pursuit of Troilus, who, preceded by Polissena and Antenore, tries in vain to escape from Troy with his father Priam….

5th zone: Symbolic groups of heraldic animals (griffins and sphinxes) between fighting land animals (lions, bulls, wild boars and deer).

6th zone: Geranomachia, that is the battle of the Pygmies against the cranes.

The handles: Ajax with the corpse of Achilles below Artemis Persica and Ker, the goddess or god of the dead.

Face B:

1st zone: For his victory over the Minotaur, Theseus acclaimed liberator of Attica by his crew, is crowned by Arianna, and to the sound of the lyre, begins the sacred dance called gerunos….

2nd zone: Theseus avenges his friend Pirithous, joining doses to him and the Lapiths to exterminate the protruding Centaurs.

3rd zone: Continuation of the epitalamic procession to the Thetideion: Ares and Aphrodite with the Muses, Apollo and Artemis with the Graces (?), Athena and Leto (?)…Hermes and…Hades and Proserpina (?), Okeanos triton and Hephaistos riding the Dionysian donkey.

4th zone: Hera, bound on the deceitful chair of Hephaistos, with Zeus enthroned beside her, she offers Aphrodite as a prize to whomever might free her. After Ares—Aphrodite’s lover—attempted in vain to free her, Hera, dejected and derided, waited patiently for her release from Hephaistos, the deceiver…who returns in triumph led by Dionysos grotesquely mounting the bacchic donkey and followed by the busty revelers (thiasos) of the Sileni and the Nymphs.

5th and 6th zones: see Face A.

Museo archeologico di Firenze, and Luigi Adriano Milani. Il R. Museo Archeologico Di Firenze: Sua Storia E Guida Illustrata. Firenze: B. Seeber, 1923, pp. 148–49.

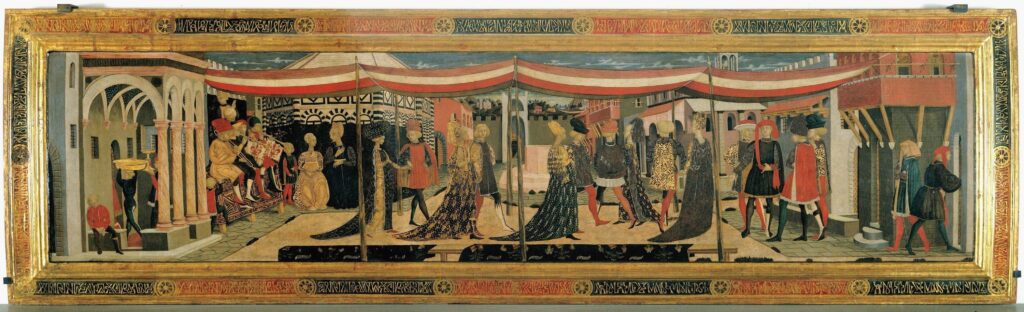

A staircase at the end of the rooms on the right leads to the upper floor of the palace, which is entirely occupied by the precious collection of church vestments and embroideries brought from confiscated convents and churches, and by the vast collection of Arazzi10Deriving a name from Arras in French Flanders. or tapestries, removed from the galleries between the Uffizi and Pitti, or brought together from the old Tuscan palaces. This collection is probably the finest in existence, extending from the XVI. to XVIII. c.

A tapestry factory was established at Florence by Nicolaus Karcher and Jan van Roost of Brussels, under Cosimo I., but flourished and failed with the House of Medici. Many of the pieces exhibited here are wrought with arms of the Medici rulers and their different alliances; others, from pictures by well-known masters, are noble works of Branconi, Roost, Termini, Fevère, and Papiri.

Notice the beautiful Florentine tapestries made after designs by Francesco Ubertini (Il Bachiacca, 1494–1557): Angelo Bronzino (1502–1572), Francesco Salviati (1510–1563), and Jacopo Pontormo (1498–1558). There are also three rooms hung with Flemish sixteenth-century work, by unidentified makers, with episodes, illustrating the lives of Caesar and Henri II.

Six pieces of Gobelins tapestry by Jean Audran (1667–1756) portray the story of Esther and Ahasuerus. Consult the Catalogue by Professor Rigoni.

Opposite the Annunziata opens the Via dei Servi, running direct to the Duomo, where No. 15 is the Palazzo Boutourlin, built by Sebastiano da Montaguto from designs of Dom. di Baccio d’Agnolo. No. 10 is the Palazzo Fiaschi, which belonged to Sforza Almeni, killed (May 22, 1566) by Cosimo I. for fear he should betray secrets which he had discovered. No. 6 stands on the site of the palace of the Del Palagio family, who founded S. Francesco at Fiesole: here also, at the corner of Via del Castelaccio, were the studios of Jacopo da Empoli and Benedetto da Majano.

S. Michelino Visdomini, rebuilt c. 1560 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Near the Duomo end of the street, on the left, is the church of S. Michelino Visdomini, with the arms of the founders on its front.11Arms: Quarterly 1 and 4 Bendy, sable and or, 2 and 3, or. The Visdomini family had the right of installing the bishops of Florence, and, during a vacancy in the see, of administering the revenues appointed for the bishops’ table. In the Pucci12Arms of Pucci: Argent, a Moor’s head filletted, argent, on the fillet, 3 hammers, crosses or T’s, sable. chapel (the 2nd right) is a fine Holy Family with SS. John and Francis by Pontormo (1518). Over the 5th altar is the miraculous crucifix of the Bianchi carried in all old Florentine processions. The original church of this title was demolished in 1363 for the purpose of enlarging the Duomo.

At the left corner of the Piazza dell’ Annunziata is the Palazzo Ricci, built by Buontalenti on the site of an earlier house of the family in which S. Caterina dei Ricci was born.

Brunelleschi, Ospedale degli Innocenti Portico, 1419-27 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Via dei Fibbiai leads into the Via degli Alfani, running E.–W. The swaddled babies over the doors on the left of this street mark the property of the Ospedale degli Innocenti. Several lovely small works of the Della Robbia school are preserved here. The Museo degli Innocenti contains numerous displays and interpretive panels detailing the history of the Ospedale, a foundling hospital established in 1445, and which served as an orphanage until 2000.

The Foundling Hospital– Spedale degli Innocenti–…one of the earliest of the kind, was founded in 1421, when Giovanni de’ Medici was gonfalonier…The management was confided to the Guild of Silk, and the building was constructed by Francesco della Luna, after a design of his master Brunelleschi, upon gardens and land belonging to the Albizzi family. The hospital was opened in 1444, and gradually acquired additional funds by the successive incorporation of smaller analogous institutions previously existing. Most of the boys admitted to the charity are brought up as field labourers, but receive aid from the institution until the age of eighteen. The girls can claim marriage dowries, and are under the guardianship of the institution until the age of thirty-five; but when younger, they are sent out as domestic servants, or are educated for a trade. Between seven and eight thousand foundlings are annually supported, though few are actually maintained within the building. The larger number, soon after admission, are dispersed among the peasantry living round Florence, who are paid for their maintenance until they are old enough to return to the institution within the city.

Susan and Joanna Horner, Walks in Florence, 2nd ed., vol. 2, pp. 130-131.

On the third floor, a long gallery, formerly a nursery and now used to display works of art, contains an early work by Botticelli, a Madonna and Child c. 1445 by Luca della Robbia, a Madonna Enthroned by Piero di Cosimo, and a beautiful Adoration of the Magi by Dom. Ghirlandajo that was once over the high-altar of the church.

On the right of Via degli Alfani are the remains of the Monastery of S. Maria degli Angeli. In the cloisters are frescoes by Andrea Castagno and Dom. Ghirlandajo. The Monastery was founded c. 1293 by Fra Guittone d’ Arezzo, a poet whom Dante introduces as mentioned by another poet, Buonagiunta of Lucca:

Ma di, s’ io veggo qui colui, che fuore

Trasse le nuove rime, cominciando:

“Donne ch’ avete intelletto d’ amore.”

Ed io a lui: “Io mi son un, che, quando

Amore spira, noto; ed a quel modo

Ch’ ei detta dentro, vo signiiicando.”

“O Frate, issa vegg’ io,” diss’ egli, ” il nodo

Che ‘I otaio, e Guittone, e me ritenne

Di quà dal dolce stil nuovo ch’ i’ odo.

Io veggio ben, come le vostre penne

Diretro al dittator sen vanno strette;

Che delle nostre certo non avvenne;

E qual più a gradire oltre si mette,

Non vede più dall’ uno all’ altro stilo.”

E quasi contentato si tacette.

But say if him I here behold, who forth

Evoked the new-invented rhymes, beginning,

Ladies, that have intelligence of love?”

And I to him: “One am I, who, whenever

Love doth inspire me, note, and in that measure

Which he within me dictates, singing go.”

“O brother, now I see,” he said, “the knot

Which me, the Notary, and Guittone held

Short of the sweet new style that now I hear.

I do perceive full clearly how your pens

Go closely following after him who dictates.

Which with our own forsooth came not to pass;

And he who sets himself to go beyond,

No difference sees from one style to another;”

And as if satisfied, he held his peace.

Dante Purgatorio 24:49–63. Trans. Longfellow.

Opposite this monastery (No. 50) is the noble Palazzo Giugni (Della Porta), with a beautiful door and cortile, built (1577) from designs of Ammannati. The Guelphic family of Giugni, distinguished in the battle of Monteaperto, claims descent from Junius Brutus. Many of its members have been distinguished as warriors, ambassadors, and orators.42

Crossing eastwards the Via della Pergola, which contains (R.) the well-known Teatro della Pergola, and where an inscription marks the house in which (No. 61) Bronzino lived, and (No. 59) where Benvenuto cast his Perseus, we reach the Via dei Pinti.Turning down it to the left, we pass, on the right, the Convent of S. Maddalena de’ Pazzi, so called from a Florentine nun of that old family, canonised in 1670. She is buried in the left transept of the church.

In the 2nd Chapel on the left is:

*Cosimo Rosselli. The Coronation of the Virgin.

In the 4th Chapel on the left:

Raffaellino del Garbo. S. Ignatius, S. Roch, and S. Sebastian: the latter carved in wood.

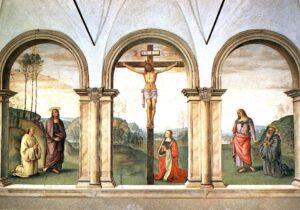

Pietro Perugino, Crucifixion with Saints, 1494-96 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Turning round the outer wall of the Convent, a door in the Via della Colonna gives admission to the Chapter-House, which contains a very beautiful fresco by Perugino of the Crucifixion. S. John and S. Benedict stand on the right, the Virgin and S. Bernard on the left. The Magdalen, in black with a red mantle, gazes, adoringly at the Saviour. The Virgin is also in black.

The landscape of Perugino for grace and purity is unrivalled; and the more interesting because in him certainly whatever limits are set to the rendering of nature proceed not from incapacity. In the landscape of S. Maria Maddalena there is more variety than is usual with him.

A gentle river winds round the bases of rocky hills, a river like our own Wye or Tees in their loveliest reaches; level meadows stretch away on its opposite side; mounds set with slender-stemmed foliage occupy the nearer ground, a small village with its simple spire peeps from the forest at the end of the valley.

John Ruskin, Modern Painters, vol. 2, p. 211.

The Palazzo Gherardesca, near the northern end of the Via dei Pinti, on the left, was built in the XV. c. by Bartolommeo della Scala, who bequeathed it to Leo XI. (Alessandro de’ Medici). Some of its rooms are beautifully decorated with frescoes of the Poccetti school. On the 1st floor is a ceiling painted by Il Volterrano.

At the corner of the Via Giuseppe Giusti, the Istituto Tecnico occupies the old convent of the Crocetta, named from a cross which its Dominican nuns affirmed to have been added to their dress by the Virgin in person. No. 62 in this street (corner) is Palazzo Panciatichi (formerly Ximenes), built for his own residence by Giovanni da San Gallo in 1490. Napoleon I. and Josephine stayed here as guests of the French ambassador. The adjoining building was a convent of the Salvestrini, and is now a school for lace-making (and selling) under Belgian nuns. Luca della Robbia was born in a house facing the convent in 1382. At 79 lived Bartolini, the

Robert Browning designer, Tomb of Elizabeth Barrett Browning (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

sculptor.

The Borgo de’ Pinti ends at the Piazzale Donatello and the Porta Pinti, just outside which is the Protestant Cemetery. It was formerly a lovely spot, backed by the old walls of the city, but these have now been removed, and the place is encircled by dusty high-roads. Here, near Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Arthur Clough, Mrs. Trollope, and the American Theodore Parker, &c., rest the remains of Walter Savage Landor, who died at No. 2671 Via Nunziatina, on Sept. 17, 1864.

Come back in sleep, for in the life

Where thou art not

We find none like thee. Time and strife

And the world’s lot

Move thee no more; but love at least

And reverent heart

May move thee, royal and released

Soul, as thou art.

And thou, his Florence, to thy trust

Receive and keep,

Keep safe his dedicated dust,

His sacred sleep.

So shall thy lovers, come from far,

Mix with thy name,

As morning-star with evening-star,

His faultless fame.

Algernon Charles Swinburne, In Memory of Walter Savage Landor.

Following the Via Giusti for a short distance (E.), we reach Piazza d’ Azeglio,13Massimo d’Azeglio (1798– 1866) was Prime Minister of Sardinia, mentor to Camillo Cavour, and advisor to Victor Emmanuel II in the years leading to the unification of Italy. planted with trees and flowers. Walking along the west side of the piazza on via Farini we come to the Synagogue and Jewish Museum (via Farini No. 6). The temple, an eclectic mix of Moorish and Byzantine styles topped with a copper-clad dome, was designed by the architects Vincenzo Micheli, Marco Treves, and Mariano Falcini. It dates from 1874–82. The small museum on the upper floors contains silver objects, vestments, and ceremonial objects. With the destruction of the Jewish ghetto in the late 19th century, the synagogue became the new spiritual home for Florentine Jews.

Continuing southward on via Farini, turn left (E.) at via dei Pilastri, where a terrible tragedy occurred in 1639.

In the reign of Ferdinand II. there lived here an elderly Florentine gentleman, Giustino Canacci, who had been twice married, and his second wife, Caterina, was celebrated for her beauty and virtue. Jacopo Salviati, Duke of San Giuliano, was among her admirers, which excited the jealousy of his duchess, Veronica Cibo, princess of Massa. She determined to get rid of one she thought a rival, and, Caterina having unfortunately incurred the hatred of her stepson, Bartolommeo Canacci, he consented to guide three assassins, hired by the Duchess, to this house, where Caterina was one evening entertaining some of her friends. Here they murdered her, with her maid, who remained beside her mistress when the rest of the family had taken flight. Caterina’s head was then cut off and taken to the Duchess, who concealed it in a basin of clean linen, which it was customary to place in her husband’s apartment on the first day of the year. The Duke uncovered the basin, and nearly fainted away on seeing its contents. Though the crime was of so heinous a nature, Bartolommeo Canacci alone suffered punishment; he was seized and beheaded, whilst the rest of the culprits escaped; the Duchess left Florence, in greater dread of the fury of the populace than the justice of the tribunals. A well in the Via de’ Pentolini still exists into which the body of Bartolommeo Canacci is said to have been thrown.

Susan & Joanna Horner, Walks in Florence, vol. 1, pp. 354–55.

Sant’ Ambrogio façade, rebuilt in 19th c. (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

From via dei Pilastri proceed to the Piazza and Church of S. Ambrogio. It consists of a plain long nave, having four over-arched altars at the sides. The choir has a side-chapel each way. To L. of door on west wall is a fourteenth-century fresco with the Martyrdom of S. Sebastian. The 2nd altar R. has a Virgin and Saints by a disciple of Lorenzo di Credi; and over the 1st altar is The Angel and Tobit, with S. Antonio, by Raffaelino del Garbo.The chief treasures of this little old-world, but at first unattractive, church are in the chapel to the L. of the choir (“Della Misericordia”). The first of these, L., is a masterpiece of Cosimo Rosselli, 1476,43 a fresco in honour of a transubstantiation-miracle which occurred in Florence. The Piazza S. Ambrogio, as it was in the artist’s day, is represented in the picture.

This truly wonderful fresco represents the translation of a miraculous chalice to the episcopal palace, and contains groups which would not be unworthy of Raphael’s brush, so much taste reigns in the general arrangement and in the way of treating all the accessory parts. . The only criticism that can be made of this masterpiece is that it has too many beauties squeezed into a small space. Among all the portraits that are accumulated there, there is one that Vasari particularly points out to the attention of the spectator: it is that of the famous Pico della Mirandola, which is, says the historian, of a striking truth. . . . . Everything in this work breathes so much devotion, hope and faith that it can be placed alongside the most exquisite productions of mystical painting.

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, vol. 1 (1861), pp. 399–400.

On the festa of San Firenze, A.D. 1230, an old priest named Uguccione, who belonged to the convent of Sant’ Ambrogio, after saying mass and consecrating the body of Christ, neglected to clean the sacred vessel, and found on the next day that the miracle of transubstantiation had taken place, and that the chalice contained living blood compressed and incarnate. This, being manifest to all the nuns of the said monastery, as well as to many neighbours, the Bishop of Florence, and the clergy, was noised abroad, and attracted crowds of devout citizens to see it; after which the blood was removed from the chalice to an “ampulla” of crystal, which has ever since been shown to the multitude with great veneration.

Karl Károly, A Guide to the Paintings of Florence, p. 179. [Hare’s footnote cites “Villari, lib. vi. ch. 8”]

Mino died in Florence, and was buried in this church (1484). The architect, Simone Pollajuolo, called Il Cronaca; the sculptor, painter and goldsmith, Andrea Verocchio, who died in Venice; and the sculptor, Lionardo del Tasso (to whom the S. Sebastian on the left of the nave is due), are likewise buried here. So this little church is peculiarly rich. Moreover, a cortile entered from left contains interesting slabs, shields, and inscriptions.

South of the church take Via dei Macci then east to via Paolieri to Mercato S. Ambrogio in Piazza Ghiberti. Built by Giuseppe Mengoni , the architect of the Mercato Centrale in San Lorenzo, in 1873.

Against a house near this church is a beautiful terra-cotta shrine of S. Zanobio, and beneath it an inscription in honour of “the Immortal Pius VII.” having given his benediction on that spot.

Vasari, Loggia del Pesce, rebuilt 1956 in Piazza Ciompi (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Returning N. on via dei Macci and then W. on via Pietrapiana we come to the Piazza Compi where Giorgio Vasari’s Loggia del Pesce was installed in 1956 after being dismantled and removed during the demolition of the Mercato Vecchio in the late 19th c.

In the 1930s the blocks bounded by via Petrapiana, via Verdi, via dell’ Agnolo, and Borgo Allegri were razed by the Fascists who intended to develop the area. However their plans came to naught and after the war rebuilding occurred without an overall plan. At the corner of via Verdi and via Pietrapiana is Giovanni Michelucci’s Sede Provinciale delle Poste e Telegrafi, 1959-67 (Provincial Post and Telegraph office). At 29, Pietrapiana, were the arms of Della Stufa, and at 48 lived Benedetto Varchi. the historian.

Down the Via Borgo Allegri we obtain in passing a fine view of S. Croce; and at No. 100, Cimabue had his studio, and gave Giotto his earliest instructions. At 96, Ghiberti lived and loved his work; and near by Antonio Rossellino painted and carved.

If we continue and take Via S. Egidio we shall reach the Hospital of S. Maria Nuova, founded by Folco Portinari, father of Dante’s Beatrice. The work was suggested to him by his servant Monna Tessa, who began it by receiving sick persons and nursing them in a room in her master’s house. The Hospital has been greatly increased and altered in after years. The Loggia was added in 1598 by Buontalenti.

Over the door of the church of S. Egidio (1478), which is annexed to the Hospital, is the Coronation of the Virgin, in terra-cotta, by Dello. On the right of the entrance is a fresco by Lorenzo de’ Bicci, representing Michele di Panzano, Governor of the Hospital, kneeling at the feet of Martin V. to receive the confirmation of its privileges. Eugenius IV., then a cathedral-canon, is seen in the blue robes of the Canons of S. Giorgio in Alga. On the left is another fresco of Panzano receiving a brief from the Pope, in front of the church of S. Maria Nuova. The ornament over the present door is seen in the fresco. The rest of the frescoes in this portico are by Pomerancio, except the Annunciation at the end, which is by Taddeo Zucchero.

In the interior, on the right, was the monument of the founder, Folco Portinari. His family are represented in a noble picture by Hugo Van der Goes, painted when Tommaso Portinari was ambassador from the Medici at Bruges, and presented by him to the Hospital. [In the Uffizi since 1900.] S. Egidio discovered in his cave is by Giunto Gimignano. A Magdalen is by Andrea Castagno.

In the Cloister are a relief believed to represent the good Monna Tessa, and a tabernacle by Giovanni di S. Giovanni. To this Hospital belongs a small gallery of pictures, entered at 29 Via Bufalini, a stone’s-throw westward still, where Ghiberti had another studio. Hither have been taken some of the pictures from the church and hospital, to which have been added several more from other sources.

In Room 2 was an important Last Judgment by Fra Bartolommeo, but finished by Albertinelli. [Now in Museo Nazionale di San Marco]

Also an Annunciation by the latter artist, and a Madonna and Saints by Fra Angelico. At No. 35 lived in the olden stormy days of the early Signoria, Dino Compagni, the chronicler, and in our day Mr. Sloane, who paid for the fronting of S. Croce. Hence, turning left down the Via de’ Servi, we find ourselves at the Duomo.

This wall-painting of S. Maria Nuova is the masterpiece of a man who almost succeeds in combining all the excellences of his predecessors and contemporaries.

Crowe and Cavalcaselle, New History of Painting in Italy, vol. 3, p. 438.

Also an Annunciation by the latter artist, and a Madonna and Saints by Fra Angelico. At No. 35 lived in the olden stormy days of the early Signoria, Dino Compagni, the chronicler, and in our day Mr. Sloane, who paid for the fronting of S. Croce. Hence, turning left down the Via de’ Servi, we find ourselves at the Duomo.