2.2: Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo

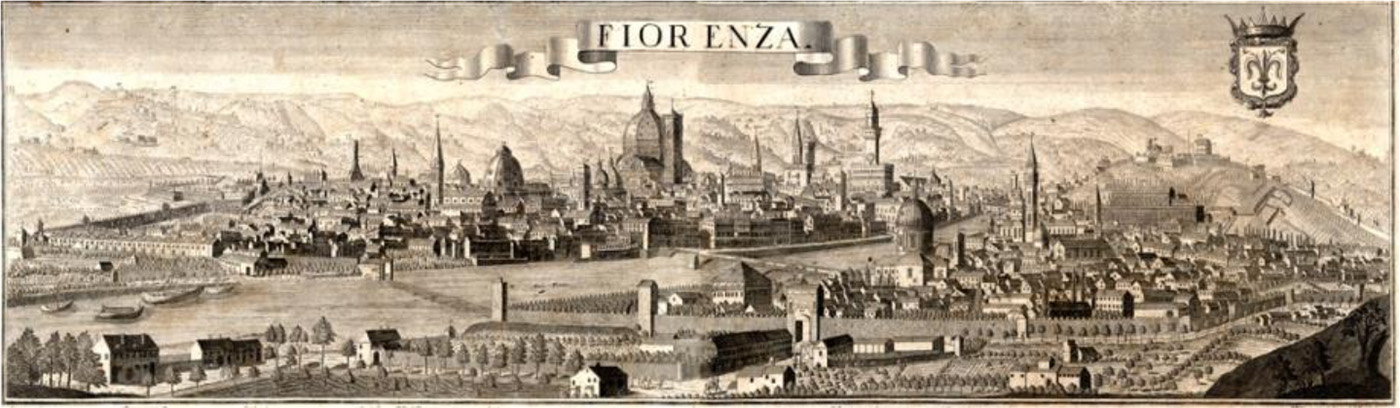

All around the northern side of the Duomo are old palaces, having arcaded rustic basements, once belonging to the Berardi and the former Opera del Duomo.1At 21 Via dei Servi, lived and worked Donatello. At the eastern angle of the piazza, is a palace marked by a bust of Cosimo I., which was at one time the residence of Lorenzo de’ Medici. An archway close to this palace leads to the Opera del Duomo or Museo di S. Maria del Fiore, which contains a most interesting collection of objects and fragments connected with the church. Founded in 1891, the Museo was completely renovated and enlarged2From approximately 2,400 to 6,000 sq. meters. in 2015 under the direction of Monsignor Timothy Verdun and architects Adolfo Natalini, Piero Giucciardini, and Mario Magni. The result is nothing short of spectacular.

Ground Floor

Sala di Paradiso (Room 6)

Bernardino Poccetti, Façade Duomo, c. 1587

The main hall, formerly a theatre and garage, has been transformed and contains a reconstruction of the Duomo’s façade as it appeared between 1420 and 1587 when it was demolished by order of Grand Duke Ferdinand I. The statues that originally ornamented the then incomplete west face of the cathedral have been inserted in the niches where they most likely appeared originally. Those works that were at the upper levels and difficult to see have been replaced with casts, and the originals are now at eye level.

Among the notable works are those by Arnolfo di Cambio and the Four Evangelists from the Duomo façade.

Arnolfo di Cambio, Virgin and Child Enthroned, 1296-1302 (center) (Opera di S.M. del Fiore)

The Virgin and Child from the original front of the Cathedral, and the original font surmounted by an angel.

Nanni di Banco, S. Luke, 1408–15 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

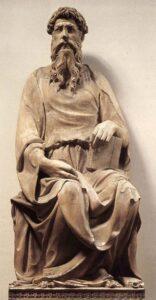

Donatello, S. John the Evangelist, 1410–11 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Bernardo Ciuffagni, S. Matthew, 1410-15 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Niccolò Aretino (Niccolò di Piero Lamberti), S. Mark, 1410–15 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

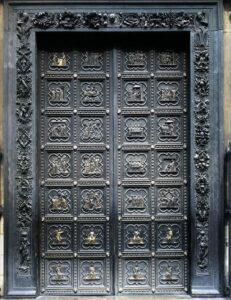

From the S. entrance of the Baptistery are the glorious Gates of Andrea Pisano, executed in 1330. Of their twenty large panels appropriately representing scenes in the life of the Baptist, the two most beautiful are those of Zacharias naming his son, and of S. John being laid in the tomb by his disciples.

In the first, Zacharias is represented as a venerable old man, writing at a table, near which stand a youth and two women, beautifully draped, and grouped into a composition whose antique simplicity of means shows how far Andrea had advanced beyond Niccola and Giovanni (Pisano), who could not tell a story without bringing in a crowd of figures. In the Burial of S. John we see a sarcophagus, placed beneath a gothic canopy, into which five disciples are lowering the dead body of their master, two at the shoulders (one of whom evidently sustains the whole weight of the corpse), and two at the feet, while a sorrowing youth holds up a portion of the winding-sheet; a monk, bearing a torch, looks down upon the face of S. John from the other side of the Area, and near him stands an old man, his hands clasped in prayer and his eyes raised to heaven. In these works we find sentiment, simplicity, purity of design, and great elegance of drapery, combined with a technical perfection hardly ever surpassed, while the single allegorical figures show the all-pervading influence of Giotto, from whom Andrea learned to use the mythical and spiritual elements of German art, as Giovanni Pisano had used the fantastic and dramatic. When they were completed and set up in the doorway of the Baptistery, now occupied by Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise, all Florence crowded to see them; and the Signory, who never quitted the Palazzo Vecchio in a body except on the most solemn occasions, came in state to applaud the artist, and to confer upon him the dignity of citizenship.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, pp. 65–66.

Lorenzo Ghiberti’s original doors from the Baptistry have been restored and installed in the Sala di Paradisio.

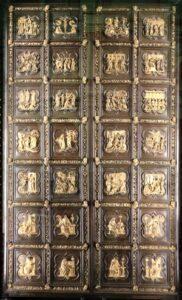

The beautiful N. Gates, of 1401, by Lorenzo Ghiberti.3Son of Cione di Ser Buonacorso di Abatino di Ghiberti. Born in 1378, he sat amongst the twelve Buonuomini in 1443, and amongst the sixteen Gonfalonieri in 1446. He bought a fine estate near Badia a Settimo, and had a house in Borgo Allegri, where he died in 1455. depicting twenty subjects from the New Testament inclosed in a marvellous frieze of foliage, fruit, and birds. Copies have replaced the originals on the Baptistery.

The northern gate is the result of that famous competition which opened the Quattro-cento. It was assigned to Lorenzo Ghiberti in 1403, and he had with him his stepfather, Bartolo di Michele, and other assistants (including, possibly, Donatello). It was finished and set up, gilded, in April 1424, at the main entry between the two porphyry columns opposite the Duomo, whence Andrea Pisano’s gate was removed. It will be observed that each new gate was first put in this place of honour, and then translated to make room for its better. The plan of Ghiberti’s is similar to that of Andrea’s gate—in fact, it is his style of work brought to its ultimate perfection. Twenty-eight reliefs represent scenes from the New Testament, from the Annunciation to the Descent of the Holy Spirit; while in eight lower compartments are the four Evangelists and the four great Latin doctors. The scene of the Temptation of the Saviour is particularly striking, and the figure of the Evangelist, John, the Eagle of Christ, has the utmost grandeur. Over the door are three finely modelled figures, representing S. John the Baptist disputing with a Levite and a Pharisee—or perhaps the Baptist between two prophets—by Giovanni Francesco Rustici (1506–1511), a pupil of Verocchio, who appears to have been influenced by Leonardo da Vinci.

Edmund G. Gardner, Story of Florence, pp. 255–56.

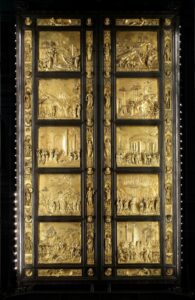

The E. Gates were executed by the same artist, 1425–1452. It was of these that Michelangelo said that they “were worthy to be the gates of Paradise.” The ten compartments represent subjects from the Old Testament. The head in the centre is said to be the artist’s portrait, and that next to it, Bartolo, his stepfather. The inscription is near them “Laurentii Cionis de Ghibertis mira arte fabricatum.” [Crafted by the wonderful art of Lorenzo Cioni of the Ghiberti.]

“In modelling these reliefs,” says Ghiberti, in his second Commentary, “I strove to imitate Nature to the utmost, and by investigating her methods of work to see how nearly I could approach her. I sought to understand how forms strike upon the eye, and how the theoretic part of sculptural and pictorial art should be managed. Working with the utmost diligence and care, I introduced into some of my compositions as many as a hundred figures, which I modelled upon different planes, so that those nearest the eye might appear larger, and those more remote smaller in proportion.”

Lorenzo Ghiberti, 2nd Commentary.

The work lasted forty years, says Vasari, that is to say one year less than Masaccio had lived, one year more than Raphael was to live. Lorenzo, who had begun it full of youth and strength, finished it old and bent. His portrait is that of that bald old man who, when the door is closed, stands in the ornament in the middle; A whole artist’s life had passed in sweat, and had fallen drop by drop on this bronze!

Alexandre Dumas, Une année à Florence, p. 219.

Each of the gates is surmounted by a group in bronze, viz.: —

Andrea Sansovino, Baptism of Christ, 1502-05 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Vincenzo Danti, Beheading of St John the Baptist, 1569-71 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Donatello, Mary Magdalene, c. 1457 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Donatello wanted it to be a mirror to penitents, not an incitement to the greed of looks, as happened to other artists.

Leopoldo Cicognara, Storia della Scultura, vol. 2, p. 44.

[The] figure of Santa Maria Maddalena, executed in wood,…is extremely beautiful and admirably finished: the penitent is seen consumed and exhausted by her rigid fastings and abstinence, insomuch that every part exhibits the perfection of an anatomical study, most accurately represented in all its parts.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Foster, vol. 1, p. 472.

Tribuna di Michelangelo (Room 10)

Formerly located behind the Duomo’s high altar, this unfinished Pietà was moved to the Museo in 1980. The inscription says it is the last work of Michelangelo, executed in 1555, when he was in his eighty-first year.

This is a group of four figures of more than life-size, namely, a Christ taken down from the cross, supported in death by his Mother, whose arms, breast, and knee appear to glide beneath his body in a wonderfully beautiful attitude: and for this purpose she is aided from above by Nicodemus, who, standing firm on his feet, sustains the body under the arms, showing great vigour and strength: and on the left side by one of the Maries, who, although filled with grief, nevertheless does not fail in giving that aid which the Mother, through her extreme sorrow, is unable to render. Christ falls lifeless with all his limbs relaxed, but in an attitude very different from that which Michelangelo designed for the Marchioness of Pescara, and from that of the Madonna della Febbre. It would be impossible to describe the beautiful expression of love that is seen in the grieved and mournful countenances of all, but especially of the sorrowing Mother: therefore let this suffice. It is without doubt a masterpiece, and one of the most difficult works which, up to the present, he has accomplished: chiefly because ail the figures are seen distinctly, nor are the garments of one blended with the garments of another….His intention is to give this Pietà to some church, and to be buried at the foot of the altar over which it will be placed.

Ascanio Condivi, Life of Michelangelo, pp. 62–63.

Michelagnolo [sic.] worked for his amusement; almost every day at the group of four figures, of which we have before made mention; but he broke up the block at last, either because it was found to have numerous veins, was excessively hard, and often caused the chisel to strike fire, or because the judgment of this artist was so severe, that he could never content himself with anything that he did, a truth of which there is proof in the fact that few of his works, undertaken in manhood, were ever completed; those entirely finished having been the productions of his youth…. And the reason of this is obvious, he had proceeded to such an extent of knowledge in art, that the very slightest error could not exist in any figure, without his immediate discovery thereof; but having found such after the work had been given to view, he would never attempt to correct it, and would commence some other production, believing that the like failure would not happen again; this then was, as he often declared, the cause wherefore the number of pictures and statues finished by his hand was so small.

When he had broken the Pietà, as related above, he gave it to Francesco Bandini, and this happened about the time when the Florentine sculptor, Tiberio Calcagni…inquired, after a long discussion, wherefore he had destroyed so admirable a performance? to this our artist replied, that he had been moved thereto by the importunities of Urbino; his servant, who was daily entreating him to finish that work: there had besides been a piece broken off the arm of the Madonna; and these things, with a vein which had appeared in the marble and had caused him infinite trouble, had deprived him of patience, insomuch that he not only broke the group, but would have dashed it to pieces, if his servant Antonio had not advised him to refrain, and to give it to some one even as it was.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Foster, vol. 5, pp. 312–13.

1st Floor

Sala del Campanile (Gallery 14), a long narrow space that contains 16 life-size statues and 54 bas reliefs removed from Giotto’s bell tower.4Copies have replaced the originals on the campanile. On either side of the statues are openings that allow visitors to see the Sala di Paradisio from an elevated vantage point.

The bas-reliefs round the basement storey of the bell tower were designed by Giotto and Andrea Pisano. The former is believed to have executed those of Sculpture and Architecture, the rest being carried out by Luca della Robbia in the 15th century. [Copies of the reliefs have replaced the originals, which are now housed in the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo.]

Of representations of human art under heavenly guidance, the series of bas-reliefs which stud the base of this Tower of Giotto must be held certainly the chief in Europe. . . . Read but these inlaid jewels of Giotto’s once with patient following, and your hour’s study will give you strength for all your life.

John Ruskin, Mornings in Florence, pp. 160–61.

In the second or succeeding tier of the campanile were sixteen statues, several of them by Donatello.

Donatello, Prophet Jeremiah, 1423-26 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Donatello, Prophet Habakkuk (“il Zuccone”), 1423-26 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Donato executed four figures [for the campanile], each five braccia high, two of which are portraits from the life, one of Francesco Soderini when a youth, the other of Giovanni di Barduccio Cherichini, now called the Zuccone [pumpkin head]. The latter is considered the most extraordinary and most beautiful work ever produced by Donatello, who, when he intended to affirm a thing in a manner that should preclude all doubt, would say, “By the faith that I place in my Zuccone.” And while he was working on this statue he would frequently exclaim, while looking at it, “Speak then! why wilt thou not speak?”

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 1, p. 341.

Other statues on display in the Sala del Campanile include:

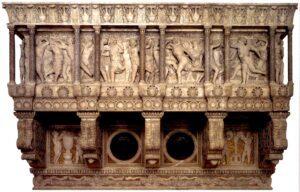

Sala delle Cantorie (Room 23) In the current installation, the cantorie are mounted above eye level as they would have been seen in the Duomo prior to being removed in 1688. The panels in the della Robbia have been replaced with copies and the originals are displayed below allowing for close inspection.

The ancient Cantoria, or singing gallery of the cathedral, by Luca di Simone (Luca della Robbia) and Marco della Robbia (1431) is inscribed with the 150th Psalm, the verses of which are illustrated by the exquisite reliefs of singing children.

They represent a band of youths, dancing, playing upon musical instruments, and singing; the expression in each chorister’s face is so true to the nature of his voice that we can hear the shrill treble, the rich contralto, the luscious tenor, and the sonorous bass of their quartette.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, p. 193.

These happy children, standing or sitting in careless ease with their varied instruments in their hands, these fair-faced boys and maidens, blowing long trumpets, sounding their harp and lyre, and clashing their cymbals as they go, singing all the while for gladness of heart, breathe the very spirit of music. Not a detail is left out, not a touch forgotten. We see the motion of their hands beating time as they bend over each other’s shoulders to read the notes, the rhythmic measure of their feet as they circle hand in hand to the tune of their own music, the very swelling of their throats as, with heads thrown back and parted lips, they pour forth their whole soul in song. Never was the innocent beauty, the unconscious grace, of childhood, more perfectly rendered than in these lovely bands of curly-headed children thrilled through and through with the power and the joy of their melody.

Church Quarterly Review, Oct. 1885.

An exquisite Cantoria ascribed to Donato di Nicolo di Betto Bardi (Donatello) (1433).

Donatello, Cantoria, 1431-39 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

[T]hose figures, so boldly sketched as we have before said, that in looking at them one almost believes them really to live and move. It may indeed be truly said of this master, that he effected as much by the superiority of his judgment as by the skill of his hand; seeing that many works are produced which appear very beautiful in the work-rooms where they are executed, but which, when taken thence and placed in another situation, in a different light or higher position, present a much changed aspect, and turn out to be the reverse of what they appeared. Donato, on the contrary, treated his figures in such a manner, that while in the rooms where they were executed they did not produce one-half the effect which he had in fact secured to them, and which they exhibited when placed in the positions for which they had been calculated.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 1, pp. 311–12.

Betto Betti, Silver Cross of the Baptistery of Saint John, 1457 (photo via Wikidata)

Sala del Tesoro (Room 25)

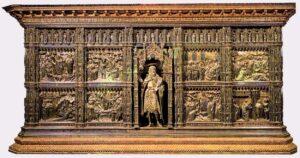

Altar of S. Giovanni, 1367-1483 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Magnificent silver dossale or altar-front of XIV. and XV. c., with twelve exquisite reliefs representing the story of S. John Baptist. This was taken every year to the Baptistery (S. Giovanni Battista) on the festival of the saint, till 1891

Magnificent silver XV. c. cross by Betto Betti, with statuettes of the Virgin and S. John by Antonio del Pollajuolo. Ordered by the Arti dei Mercanti to contain a relic of the true Cross.

At the: corner of the next street, Via dell’ Orivolo (orologio), is a palace; formerly belonging to the Guadagni with their shield (gules, a. cross engrailed, or).

Coming down the Via del Proconsolo from the Duomo we pass on the left the little church of S. Maria in Campo, in which lie the bishops of Fiesole. At No. 21 is Dotti’s old bookshop.

Bernardo Buontalenti, Palazzo Nonfinito (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

At No. 12, on the left, is the Palazzo “Nonfinito” (the never-finished), built by Buontalenti (1536–1608) up to a certain point, on the site of the former Loggia dei Pazzi, for Alessandro Strozzi. It now serves the purposes of Post and Telegraph offices. [Currently the Palazzo Nonfinito is the home of the Museo di Antropologia.] At the next corner, where the Via degli Albizzi turns off, stood the town gate of San Piero Maggiore in the ancient circuit of the walls.

Beyond stands the grand old Quaratesi Palace, originally Pazzi, whose shield is set on the angle two dolphins addorsed between five daggers. It has nine windows to the street, and they are biforate with rich mouldings. The angle bears a fanale by Niccolò Caparra.