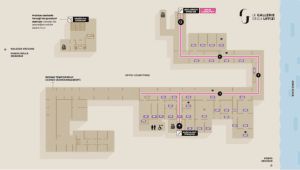

1st Floor Plan (photo Le Gallerie degli Uffizi)

3.2B: Uffizi Galleries, 1st Floor

The galleries on the First Floor continue to be expanded, renovated and re-installed. Consequently some works may not be located as shown.

Rooms B1-B9 contain works from the Alessandro Contini Bonacossi Collection. Bonacossi (d. 1955) donated his collection, one of the most important created in Italy in the 20th century, to the Italian State. The collection, formerly housed in the Palazzo Pitti, spans the 13th to the 18th centuries and includes works by Sassetta, Bellini, Bernini, El Greco among others.

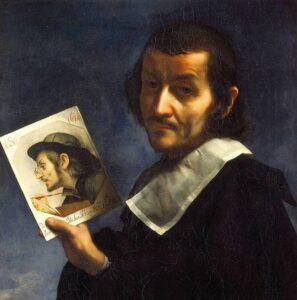

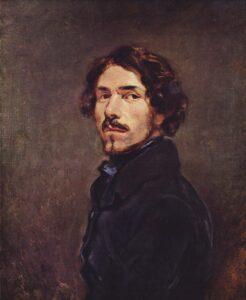

Rooms C1-C14 contain artists’ Self-Portraits. Numbering in excess of 1,750 works, this unique collection was begun by Cardinal Leopoldo de’Medici (d. 1675) and consists of works dating from the 16th century to the present day.

Galleries D1-D35 cover the 16th-18th centuries.

Room D1 Pautilla Nelli Hallway

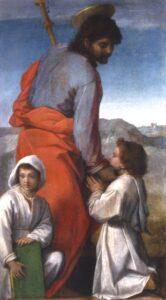

Room D2 Andrea del Sarto (Andrea d’Agnolo, 1486-1530)

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 3, pp. 252–53

Such are still commonly used in the religious processions of Italy. In this instance the picture has a peculiar form, high and narrow, adapted to its special purpose. S. James wears a green tunic and a rich crimson mantle; and as one of the purposes of the Compagnia was to educate poor orphans, they are represented by the two boys at his feet. The picture suffered from the sun and the weather, to which it had been a hundred times exposed in yearly processions; but it has been well restored, and is admirable for its vivid colouring as well as the benign attitude and expression.

Anna Jameson, Sacred Art and Legendary Art, vol. 1, pp. 238–39.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 3, pp. 262–63.

Mentioned by Vasari. This picture was painted for the Certosini of San Lorenzo al Monte and placed in the Foresteria, or Dispensa, of the convent. It was removed, after the suppression of the monasteries, to the Academy. The composition is derived from Dürer’s woodcut “Christus und die Jünger von Emmaus.” In type and treatment, however, our canvas is less

Düreresque than the frescoes of the cloister at the Certosa.

Frederick Mortimer Clapp, Pontormo: His Life and Work, p. 114.

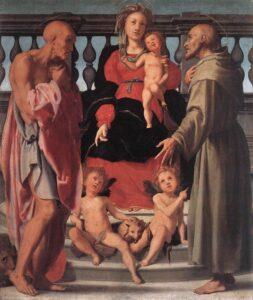

In the centre, the Madonna seated on the throne facing the spectator; her hair is brown and she wears a red dress and a blue-green mantle edged with gold the ample folds of which lie across her knees; her right hand points downward to the angels at her feet, her left hand supports the Christ Child who stands on her left knee, his left leg bent, his right hand raised in benediction. At the foot of the throne on the right of the virgin, St. Francis seen in profile to left, his left arm extended at his side, his right laid upon his breast; his robe is grey. On the left, St. Jerome, profile right and dressed in a blue grey tunic and blue-pink drapery, his hands clasping to his breast a stone. In the centre on the steps of the throne, two little angels seated, facing, with a lamb between them; they have auburn hair and dark wings edged with gold. In the background, which is dark grey, the outlines of the throne are dimly visible.

Frederick Mortimer Clapp, Pontormo: His Life and Work, p. 135.

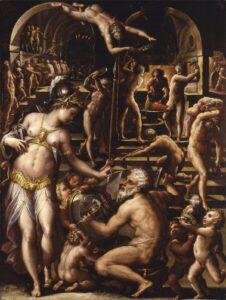

Painted for Bartolomeo Bettini from a cartoon drawn by Michelangelo (Vasari, VI, 277). Bettini planned to place it in a room of his decorated by Bronzino with portraits of Tuscans who had written of love: Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio and others. Certain interested people, however, took the panel almost by force from Pontormo and gave it to the Duke Alessandro who paid him fifty “scudi” for it. As a result of this high-handed action, for which Jacopo could hardly be held responsible, Michelangelo was alienated from our master. The painting was famous throughout the sixteenth century. Varchi speaks of it in the following terms: “One does not say that men themselves have fallen in love with marble statues, as happened to the Venus of Praxiteles, although this same still happens all day today in the Venus that Michelagnolo drew for M. Bartolommeo Bettini, colored by the hand of M. Jacopo Pontormo.” 1“Non dice egli che gli uomini medesimi si sono innamorati delle statue di marmo, come avvenne alla Venere di Prassitele, benchè questo stesso avviene ancora oggi tutto il giorno nella Venere che disegnò Michelagnolo a M. Bartolommeo Bettini, colorita di mano di M. Jacopo Pontormo.” Varchi. Due Lezzioni, Florence, 1549, p. 104.

Frederick Mortimer Clapp, Pontormo: His Life and Work, p. 142.

Sebastiano did certainly surpass all others in the painting of portraits; in that branch of art no one has ever equalled the delicacy and excellence of his work…

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, trans. Blashfield, vol. 3, p. 328.

Room D10 Painters from Ferrara

Garofalo (Benvenuto Tisi, 1476/1481 – 1559), Saint James the Greater, 1510-20

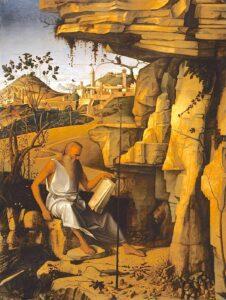

Garofalo (Benvenuto Tisi, 1476/1481 – 1559), Saint Jerome in Meditation, 1520-30

Room D11 The 16th century in Bologna

Bartolomeo Passerotti, Homer and the Riddle of the Lice, c. 1570-75

Guido Reni. Susanna (given in 1895)

Room D12 Bachiacca – The Florentine Portraits

By public and open virtues, and secret and hidden faults, he made himself the head and little less than the ruler of a Republic, which, though free, yet served.

Benedetto Varchi.

While he shunned the external signs of despotic power he made himself master of the State. His complexion was of a pale olive; his stature short: abstemious and simple in his habits, affable in conversation, sparing of speech, he knew how to combine that burgher-like civility for which the Romans praised Augustus, with the reality of a despotism all the more difficult to combat because it seemed nowhere and was everywhere.

J.A. Symonds, Sketches and Studies in Italy, p. 141.

El Greco, Saint John the Evangelist and Saint Francis, 1600

Room D20 El Greco (Dominikos Theotokopulos, 1541 – 1614)

Room D21 Antechamber of Venus

Room D22 Titian (Tiziano Vecelli, 1488/90 – 1576)

Titian, Venus of Urbino or’La Venere del Cagnolino’ (of the little dog). From the Urbino collection.

Conscious and triumphant without loss of modesty.

Crowe and Cavalcaselle, The Life and Times of Titian, vol. 1, p. 390.

The Venus di Medici must always charm women; the Venus of Titian, men.

Lady Blessington, Idler in Italy, p. 211.

She is a courtezan, but also a lady; in those days the former did not efface the latter. Hippolyte Taine, Florence, p. 142.

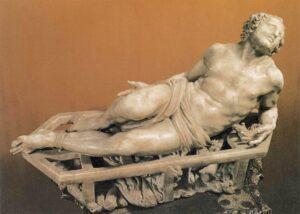

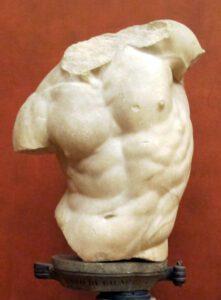

Gaddi Torso, 2nd c. BCE (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Room D27 Verone

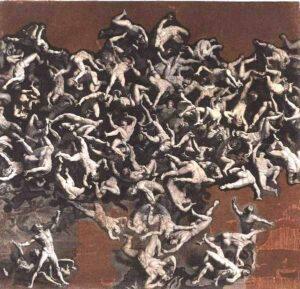

Gaddi Torso, 2nd century BCE, is an outstanding example of Pergamene School Hellenistic art. Identified by Hare as “315. Torso of a Faun” (6th edition, p. 40), the torso is now thought to be that of a struggling centaur. The Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs is a motif that occurs repeatedly in Classical art, and symbolizes the conflict between civilization and barbarism, between humankind’s elevated and base instincts. Like the Vatican’s Belvedere Torso, the Gaddi Torso escaped the fate of so many ancient sculptures in that in was never completed by restorers.

The provenance of the Gaddi Torso is incomplete. Vasari suggests that it might have once belonged to Lorenzo Ghiberti:

Lorenzo… bequeathed many relics of antiquity to his family, some in marble, others in bronze… He also left the torsi of many figures, with a great number of similar things, which were all dispersed; and, like the property acquired by Lorenzo, suffered to be destroyed and squandered. Some of these antiquities were sold to Messer Giovanni Gaddi, then “Cherico di Camera.”

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 1, p. 218.

Grand Duke of Tuscany Leopold I. purchased the torso from the Gaddi heirs in 1778. The 6th edition of Florence locates the sculpture in the Hall of the Hermaphrodite, and the 9th edition indicates that it—still identified as “Torso of a Faun”—has moved to the 2nd Vestibule.

Lo Spinario is a Roman reproduction of the well-known bronze statue in the Capitoline (Conservatori) Museum in Rome. How great a favourite the statue became, and the interesting controversies to which its motive has given rise, will best appear by quoting from Helbig’s account of the Roman example:

The aim of the artist was to reproduce, as strikingly as possible, a motive borrowed directly from Nature, and he has succeeded in producing a work the naïve simplicity of which exercises a peculiar charm. The external composition is in so far defective that the beholder can find no standpoint from which the lines of the statue form a harmonious whole. We see a boy extracting a thorn from his foot. The close attention with which he devotes himself to this task is specially expressed in the half-opened mouth and the protrusion of the lower lip. His long hair does not hang down over his cheeks, as the bent position of the head would necessitate, but clings closely to his skull ; the artist, however, seems to have knowingly followed this arrangement in order not to further obscure the face, which is already partly concealed by the position of the head. This figure is the product of an art which stands on the verge of the freer style but has not entirely broken with the traditions of archaism. The latter assert themselves in the severe treatment of the hair, the massive chin, and the leanness of the body, while the manipulation of the nude, on the other hand, betokens an already advanced stage of realism. The head resembles that of the so-called Apollo in the W. pediment of the temple of the Olympian Zeus; and the objective manner in which the artist has handled a motive taken from daily life also finds analogies in the sculptures of that sanctuary. We may therefore, perhaps, connect the figure before us with the Peloponnesian school which supplied the decoration of the temple of of which was influenced by the Peloponnesian school. To the conclusion that the statue goes back to the fifth century B.C., two main objections have been raised. The first of these is the assertion that the arrangement of the hair is contrary to the spirit of the earlier Greek art, which laid so great a stress upon a true reproduction of Nature. In the paintings of archaic vases, however, we sometimes meet stooping figures whose hair is arranged like that of the Thorn Extractor, and for the same purpose. In the second place it has been objected that the sculpture before us belongs to the realm of genre; and that, as genre figures in the proper sense of the term are not known to have existed before the reign of Alexander the Great, it cannot have been produced before this period. The motive of the figure, however, by no means excludes the possibility of its having been inspired by some definite event or by some mythical or historical tradition. If we admit this assumption, the Thorn Extractor falls out of the ranks of genre figures strictly so called and may easily find a place in the development of the earlier Greek art. In this connection reference has very justly been made to the legend of the Ozolians of Locris. Their ancestor Locros, having had his foot pierced by a thorn, recognised in this accident the fulfilment of an oracle, and founded the towns of the Locrians in the district in which his injury compelled him to linger. Other hypotheses, however, are equally admissible. Thus the statue may have been a votive offering to commemorate the victory of a boy in a foot-race, who had vanquished all his competitors in spite of having trodden on a thorn. A marble statue recently found on the Esquiline and now in the British Museum, which in every respect makes the impression of an original Hellenistic work, represents the same motive as the Capitoline example, but with vulgar forms and in a completely realistic style. It proves that the Hellenistic art, which so often transformed ideal types into realistic and especially into rustic figures, has done so in the case of the figure before us. The fifth century type has been transmuted into a genre figure in the proper sense of the term and represents nothing more than a Street Arab or a country boy picking a thorn out of his foot.

Wolfgang Helbig, Guide to the Public Collections of Classical Antiquities in Rome, vol. 1, pp. 457-59.

Room D34 Rembrandt (Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 1606-1669), Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641)

“Rembrandt,” as Koloff says, “carries a dark lantern under his cloak, which he suddenly produces and holds in our faces, so that at first we can see nothing for the blaze of light.” His light is a peculiar one that suddenly falls full into the darkness, and streams out of it again just as warmly. With its rays and reflexes it calls up the rich play of light and shade, the bright glitter of the colours; at one time it obscures them, and then again allows them to shine forth gloriously and to glow in the richest tones; it is a light that seems to shine through and through, to betray the most secret thoughts, the most hidden feelings, to put the spectator in the most intimate connection with the subject represented. “Rembrandt only paints with the aid of light,” as Fromentin says; “he only draws with light. He has a way of placing things at a distance, of bringing them near, of concealing or making them distinct, and of transforming reality into visionary semblance, which is true art, and above all the art of chiaroscuro.”

Wilhelm von Bode, Great Masters of Dutch and Flemish Painting, p. 16.

The Uffizi picture with its broad frontal arrangement and ornate costume, recalls Renaissance portraits of the time of Mabuse and Holbein, but its strong chiaroscuro lends it a definite Baroque flavor. The expression is hardly less tragic than in the small oil sketch at Aix. But the artist here expresses his own gloomy mood with an uncompromising, almost cold detachment that has little of the mellowness of other late self-portraits, yet much of their majestic character.

Jakob Rosenberg, Rembrandt, vol. 1, p. 33.

Room D35 Galileo and the Medici

Born in Pisa, then under the duchy of Florence, Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) was no stranger to controversy. In 1613 he became enmeshed in an argument regarding whether the sun or the earth moved around the other. The dispute had come to a head when Grand Duke Cosimo II, whom Galileo had tutored as a youth, hosted a dinner in which arguments against heliocentrism were raised. Galileo, who had not attended the fête, responded in a letter to Benedetto Castelli, his former student, that the Bible had authority in matters of faith and religion, but not in science. Two years later in 1615, Galileo followed up this argument in a lengthy letter to Christina, the Dowager Duchess, wife of Grand Duke Ferdinando I and mother of Cosimo II. The following year, The Congregation of the Index, better known as the Inquisition, declared heliocentrism to be contrary to the Faith and ordered Galileo cease promulgating the idea.

Galileo steered clear of the matter until 1632 when he revisited the topic in Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, which led to a further hearing before the Inquisition. He was found to be “suspect of heresy,” condemned to a life sentence of house arrest, and his Dialogue banned. In 1634 Galileo returned to Florence where he lived the remainder of his life under the protection of Grand Duke Ferdinando II, son of Cosimo II.