8.3: Excursions from Porta alla Croce, Porta Romana, Porta S. Frediano, Porta al Prato

___________

From the Porta alla Croce (S. Salvi).

A little beyond the Porta alla Croce c. 1284, in the Piazza Beccaria designed by Guiseppi Poggi we pass the Ponte d’ Affrico, where Corso Donati, fleeing from Florence and pursued by the soldiers of the Signoria, September 15, 1308, fell from his horse, and was killed by striking his head upon a stone. Here Cecco D’Ascoli was burned September 16, 1327, all Florence looking on.

Just S. of Piazza Beccaria, named for the Marquis Beccaria (1738-94), an Englishman who attempted to reform the legal system to treat all equally, is the Headquarters of the State Archives, 1972-88 by Italo Gamberini. Bounded by viale Giovane Italia and viale Giovanni Amendola, the Archives occupy a triangular piece of land. On the E. wing facing viale Amendola, the cantilevered floors jut out progressively as they ascend the side of the building. The State archives were formerly housed in the Uffizi.

About 1 mile from the gate, on the road to Rovezzano, is the Convent of S. Salvi (Via di S. Salvi, 16), on the site of an oratory erected in the XI. c. on a spot then called Partinule. It contains, in its ancient Refectory, the famous Cenacolo of Andrea del Sarto.

This work is indeed, as it is held to be, among the most animated, whether as regards design or colour, ever executed by the hand of our artist, nay, rather that could be effected by any hand; it gives proof of admirable facility, and the master has imparted grandeur, majesty, and grace, to all the figures, insomuch, that I know not what to say of this Supper that would not be too little, seeing it to be such that all who behold it are struck with astonishment. We are therefore not to be surprised if its excellence formed the safeguard of the building in the siege of Florence, in the year 1529, when that convent was suffered to remain standing while the soldiery and spoilers, by command of those who were ruling, destroyed all the suburbs, demolishing and razing to the ground all the monasteries, hospitals, and every other edifice situate without the walls. They were proceeding in truth to tear down a part of the Convent, having already ruined the church and Campanile or bell tower of San Salvi, and had arrived at the Refectory where this Last Supper is; but when the officer by whom they were led saw this work, having probably heard people speak of it, he would not permit so wonderful a painting to be destroyed, and, abandoning the place, determined that it should be injured no further, unless it should be found that nothing short of its total destruction would suffice.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 3, pp. 286–87.

The Cenacolo of Andrea del Sarto takes, I believe, the third rank after those of Leonardo and Raffaelle. He has chosen the self-same moment, “One of you shall betray me.” The figures are, as usual, ranged on one side of a long table. Christ, in the centre, holds a piece of bread in his hand; on his left is S. John, and on his right S. James Major, both seen in profile. The face of S. John expresses interrogation; that of S. James interrogation and a start of amazement. Next to S. James are Peter, Thomas, Andrew; then Philip, who has a small cross upon his breast. After S. John come James Minor, Simon, Jude, Judas Iscariot, and Bartholomew. Judas, with his hands folded together, leans forward, and looks down, with a round mean face, in which there is no power of any kind, not even of malignity. In passing from the Cenacolo in the S. Onofrio to that in the Salvi, we feel strongly all the difference between the mental and moral superiority of Raffaelle at the age of twenty and the artistic greatness of Andrea in the maturity of his age and talent. This fresco deserves its high celebrity. It is impossible to look on it without admiration, considered as a work of art. The variety of the attitudes, the disposition of the limbs beneath the table, the ample tasteful draperies, deserve the highest praise; but the heads are deficient in character and elevation, and the whole composition wants that solemnity of feeling proper to the subject.

Anna Jameson, Sacred Art, vol. 1, pp. 271–272.

Benedetto da Rovezzano (c. 1507), reliefs from the tomb of S. Giovanni Gualberto in the monastery, now museum, of S. Salvi, where soldiers were quartered in 1530, by whom they were terribly mutilated. The figures, however, glow with expression and power. The face of the dead saint has fortunately escaped. The S. Giovanni Gualberto shrine was the masterpiece of the sculptor. In 1925 the reliefs were in the Bargello as noted in the 9th edition of Florence.

After being left for fifteen years in the sculptor’s studio outside the Porta Santa Croce, on account of the violent dissensions of the monks who had ordered it, the monument was broken to pieces by the Papal and Imperial soldiers during the siege of 1530. Of the many life-sized statues belonging to it, which stood in niches divided by pilasters, none escaped; and of its bas-reliefs but five: —

1. San Pietro Igneo passing unscathed through the flames by the help of S. Giovanni Gualberto.

2. The monk Fiorenzo liberated from a demon.

3. The death and funeral of the saint.

4. The removal of his body from Passignano.

5. The monks of S. Salvi attacked by heretics.

Though many of these figures are sadly mutilated, enough remains to attest their original excellence. The most beautiful relief is perhaps that of the funeral procession, in which the saint lies on a bier, which is borne aloft on the shoulders of monks. An angel with open wings walks beside the corpse, and a boy possessed with a devil, who has been brought to meet it in hope of cure, struggles in the arms of his keepers. His distressed countenance and writhing form contrast most strikingly with the calm repose of the dead saint and the bright beauty of the attendant angel.

Another excellent composition is that in which San Giovanni is represented beside the couch of the monk Fiorenza, who covers his face with his hands to shut out the sight of the demon, from whom he has been delivered by the saint’s prayers. The other three bas-reliefs are mere fragments; hardly a head remains upon any one of the figures.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, pp. 258–59.

The parish church has some good pictures by Raffaellino del Garbo and others; in the portico is a S. Michael by Benedetto da Rovezzano.

In the fields between S. Salvi and the Via del Pontassieve is the Palazzo del Guarleone, which once belonged to the abbess of Vallombrosa. Here Henry VII. encamped before the hostile city in 1312, and was baffled. It was here that Benedetto da Rovezzano worked for ten years at the marvellous reliefs intended to adorn the tomb of S. Giovanni Gualberto; but they were never taken to their destination, and remaining in the Palazzo del Guarleone, were mutilated by the imperial soldiers, who took possession of it during the siege of Florence.

It is by the Porta S. Croce the traveller must leave Florence for the monasteries of the Casentino, if he begins his excursion by driving to Pelago (see ch. vii.).

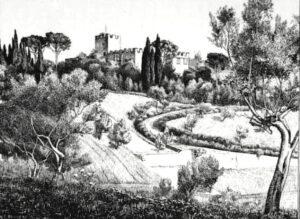

Bus no. 10 departs Stazione Santa Maria Novella and Piazza San Marco to La Mensola, at the foot of the hill of Settignano. It passes the Villa Fontebuono, where Varchi wrote his “Storia Fiorentina.” A hill on the left at two miles is crowned by the fine old castellated villa of Poggio Gherardo, which belonged to the Magaldi, who sold it to the Baroncelli in 1331. (Subsequently it was the residence of the historian and author Janet Ross (1842–1927).

It was bought by the Gherardi in 1433, not long before the great plague of Florence, and they held it until I888.1Arms of Gherardi: Or, a cross engrailed azure, on a canton four stars. This was the Primo Palagio del Rifugio of the “Decamerone,” and is described by Boccaccio, who himself spent four days here. It looks down upon the magnificent plain watered by the Affrico and Mensola, sung by Boccaccio in his “Ninfale Fiesolano.” Being one of the line of fortresses erected to defend Florence against the Casentino (Poggio, Vincigliata, Poggio Gherardo, Torre dei Gandi, &c.), the house was partially destroyed by Sir John Hawkwood.

San Martino a Mensola, Nave (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Below it is the very ancient church of S. Martino a Mensola, which was restored by S. Andrew, the companion of S. Donatus, the Irish missionary bishop of Fiesole. He established a monastery near the church, where he died soon after his master, miraculously comforted on his deathbed by the presence of his sister Bridget, whom he had left in Ireland forty years before, and in a glorious radiance of light “which drew all the people of Fiesole around him, as if summoned by a heavenly trumpet.” After his death Bridget lived in a hermitage at Opacum, now Labaco, high in the mountains, till her death in 870. The embalmed body of S. Andrew rests beneath the high-altar. Formerly the holy-water bason rested on a pedestal inscribed “Help, Help, Ghod”—a relic of the Irish S. Andrew’s rule. Some ancient arches and several curious pictures2Attributed to Bernardo Orcagna, Fra Angelico, Neri de’ Bicci, and Cosimo Rosselli. remain in the church, which was restored in 1281, in 1340, and finally by the Gherardi in 1450. The church in the Via dei Magazzini at Florence was founded by S. Andrew in 786 in connection with S. Martino a Mensola.

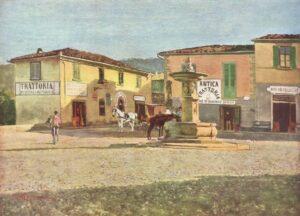

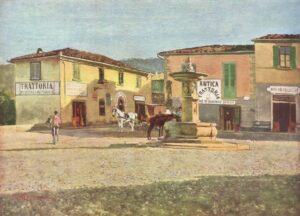

Telemaco Signorini, View of the Piazzetta of Settignano, c. 1880 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Settignano claims to derive its name from Septimius Severus. It was the native place of many great sculptors, especially of the famous Desiderio, by whom there is a beautiful relief in the oratory of SS. Trinità.

In the piazza is a statue of the patriot Niccolò Tommaseo, buried in the cemetery.

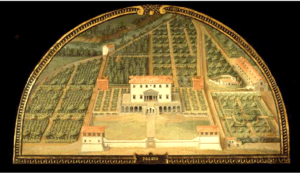

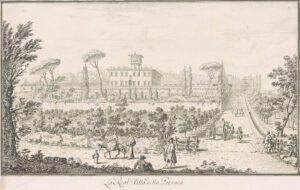

Giuseppi Zocchi, Villa Gamberaia, c. 1744

Near Settignano is the Villa Buonarotti, which, till quite recently, remained in the family, but is now the property of Count Telfy Zima. At what time this came into the Buonarotti family is uncertain, but it is tolerably certain that Michelangelo was sent out here as a baby, after Italian custom, to be nursed in a family of scarpellini or stone-cutters. On a wall in one of the rooms may still be seen the famous satyr which Michelangelo is said to have drawn with a burning stick taken from the fire. Another villa near Settignano is Gamberaja, which belonged in the XV. c. to the Gamberelle, then passed (1592) to the Riccialbani, who rebuilt it. The Villa Verone or Del Turco once belonged to the Portinari; the Villa Bourbon del Monte to the Strozzi, then to the Salviati. The little Oratory of Vannella, in the valley of Fossataccio, contains a Presentation of the Virgin by Filippo Lippi.

Porta Romana (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

From the Porta Romana—Poggio Imperiale; the Certosa of the Val d’ Ema and the Sanctuary of the Madonna dell’ Impruneta; Bellosguardo.

By the street opposite the gate we soon reach the church of S. Gaggio, occupying the site of a tower where the Paterini took refuge from S. Peter Martyr in the XIII. c. A convent was founded here by Donna Nera Manieri, and enriched by the Corsini as a retreat for the wives and daughters of the Cavalieri Gaudenti, a noble corporation devoted to peacemaking and charity. Behind the high-altar is the tomb of the foundress, and that of Donna Ghita Corsini. Other Corsini monuments have been taken hence to S. Spirito. The street, right, on issuing from the gate follows the old walls, and is called Via Petrarca.

Close to the gate on the left is the entrance of the fine cypress avenue of Poggio Imperiale, adorned with statues of Dante and Petrarch from the old façade of the cathedral destroyed in 1587. The avenue leads to a palace built for the Grand-Duchess Maddalena of Austria, wife of Cosimo II. Since 1865 it has been the Conservatorio della SS. Annunziata (Istituto Statale della Ss. Annunziata) for the education of young women of the “better classes,” by which was meant daughters of the nobility.

This palace was formerly the Baroncelli villa. It is said that a member of that ancient family, Tommaso Baroncelli, most devotedly attached to Cosmo I., having gone from his villa to meet his master returning from Rome, was so enraptured on learning he had received the title of grand duke from the pope [Pius V.], that he died of joy, an instance of enthusiasm in servitude that must appear strange nowadays!

Antoine Claude Valéry, Historical, Literary, and Artistical Travels in Italy, p. 386.

After the Baroncelli, the villa which first occupied this site belonged to the Salviati, then to the Medici. Cosimo I. gave it to his daughter Isabella, the very unfaithful wife (1563) of Paolo Giordano Orsini, by whom she was strangled in her bedroom.

The existing palace now contains little of interest except frescoes by Matteo Rosselli depicting the story of the Medici.

It was here that the famous political duel was fought by Ludovico Martelli and Dante da Castiglione against Giovanni Bandini and Bertino Aldobrandini. In this palace also, when Carlo Alberto of Sardinia was living here in exile, his infant son Vittorio Emanuele was with difficulty saved from being burnt to death by his nurse.

Behind the palace rises the hill of Arcetri, celebrated for its sweet wine called La Verdea: —

Altri beva il Falerno, altri la Tolfa,

Altri il sangue che lacrima il Vesuvio;

Un gentil bevitor mai non s’ingolfa

In quel fuoso e fervido diluvio,

Oggi vogl’io che regni entro a’ miei vetri

La Verdea soavissima d’Arcetri.

Let others drink Falernian, others Tolfa,

Others the blood that wild Vesuvius weeps;

No graceful soul will get him in the gulf o’

Those fiery deluging, and smoking steeps.

To day, methinks, ‘twere fitter far, and better, eh?

To taste thy queen Arcetri.

Francesco Redi, Bacchus in Tuscany, p. 39. Trans. Leigh Hunt.

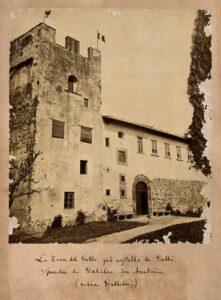

Torre del Gallo (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

In the chapel of the delightful Villa Capponi (which is passed on the way to Arcetri) is a fine “Adoration of the Shepherds” by Tommaso di Stefani, a pupil of Lorenzo di Credi.

Close by, on a hill top, on the left of the road, is the Torre del Gallo, which is believed to have been the observatory of Galileo, where, when a prisoner, he studied the moon.

The moon, whose orb

Through optic glass the Tuscan artist views

At evening from the top of Fiesole,

Or in Valdarno, to descry new lands,

Rivers, or mountains in her spotty globe.

John Milton Paradise Lost 1:287–91.

It was just in that loveliest moment when winter melts into spring. Everywhere under the vines the young corn was springing in that tender vivid greenness that is never seen twice in a year. The sods between the furrows were scarlet with the bright flame of wild tulips, with here and there a fleck of gold where a knot of daffodils nodded. The roots of the olives were blue with nestling pimpernels and hyacinths, and along the old grey walls the long, soft, thick leaf of the arums grew, shading their yet unborn lilies.

The air was full of a dreamy fragrance; the bullocks went on their slow way with flowers in their leathern frontlets; the contadini had flowers stuck behind their ears or in their waistbands; women sat by the wayside, singing as they plaited their yellow curling lengths of straw; children frisked and tumbled like young rabbits under the budding maples; the plum-trees strewed the green landscape with flashes of white like newly fallen snow on Alpine grass slopes; again and again amongst the tender pallor of the olive woods there rose the beautiful flush of a rosy almond-tree; at every step the passer-by trod ankle-deep in violets.

About the foot of the Tower of Galileo ivy and vervain, and the Madonna’s herb and the white hexagons of the stars of Bethlehem grew amongst the grasses; pigeons paced to and fro with pretty pride of plumage; a dog slept on the flags; the cool, moist, deep-veined creepers climbed about the stones; there were peach-trees in all the beauty of their blossoms, and everywhere about them were close-set olive-trees, with the ground between them scarlet with the tulips and the wild rose bushes.

From a window a girl leaned out and hung a cage amongst the ivy-leaves, that her bird might sing his vespers to the sun.

Who will may see the scene to-day.

The world has spoiled most of its places of pilgrimage, but the old Star Tower is not harmed as yet, where it stands amongst its quiet garden-ways and grass-grown slopes, up high amongst the hills, with sounds of dripping water on its court, and wild wood-flowers thrusting their bright heads through its stones. It is as peaceful, as simple, as homely, as closely girt with blossoming boughs and with tulip-crimsoned grasses now as then, when, from its roof in the still midnight of far-off time, its master read the secrets of the stars.

Ouida, Pascarèl, vol. 2, pp. 88–92.

Nearer we hail

Thy sunny slope, Arcetri, sung of old

For its green vine; dearest to me, to most,

As dwelt on by that great astronomer,

Seven years a prisoner at the city gate,

Let in but in his grave-clothes. Sacred be

His villa (justly it was called the Gem)!3Il Giojello.

Sacred the lawn, where many a cypress threw

Its length of shadow, while he watched the stars!

Sacred the vineyard, where, while yet his sight

Glimmered, at blush of morn he dressed his vines,

Chanting aloud in gaiety of heart

Some verse of Ariosto!—There, unseen,4Milton went to Italy in 1638, and visited Galileo, who, by his own account, had already become blind. In December 1637 he was forced to reside at Arcetri by an order of the Inquisition.

Gazing with reverent awe—Milton his guest,

Just then come forth, all life and enterprise;

He in his old age and extremity

Blind, at noonday exploring with his staff;

His eyes upturned as to the golden sun,

His eyeballs idly rolling. Little then

Did Galileo think whom he received:

That in his hand he held the hand of one

Who could requite him—who would spread his name

O’er lands and seas—great as himself, nay, greater;

Milton as little that in him he saw,

As in a glass, what he himself should be,

Destined so soon to fall on evil days

And evil tongues—so soon, alas! to live

In darkness, and with dangers compassed round,

And solitude.

Samuel Rogers, Italy.

It is difficult to conceive what Galileo must have felt, when, having constructed his telescope, he turned it to the heavens, and saw the mountains and valleys in the moon. Then the moon was another earth; the earth another planet; and all were subject to the same laws. What an evidence of the simplicity and magnificence of nature.

But at length he turned it again, still directing it upward, and again he was lost: for he was now among the fixed stars; and if not magnified as he expected them to be, they were multiplied beyond measure.

What a moment of exultation for such a mind as his! But as yet it was only the dawn of day that was coming; nor was he destined to live till that day was in its splendour. The great law of gravitation was not yet to be made known: and how little did he think, as he held the instrument in his hand, that we should travel by it as far as we have done; that its revelations would ere long be so glorious!

Sir John Herschel.

The tower and its surroundings have greatly suffered under the present proprietor.

Close to the Porta Romana is the Pottery of the Fratelli Cantagalli, in which a manufactory of artistic maioliche—decorative and useful—has recently been established. The proprietors have aimed at reviving the decorative taste which inspired artists of the sixteenth century in the famous potteries of Cafaggiolo, Urbino, Pesaro, and Gubbio. All the artists employed have been taught by the study not only of the ancient maioliche in the different Italian museums, but of the fifteenth and sixteenth century frescoes. It is thus sought to give the manufacture an exclusively Italian character.

A road which turns to the right at the Pian dei Giullari leads to S. Margherita a Montici, with fine views.

We get out after we have passed the gate and ascend through the garden of vines and olives and young bright wheat to the Abbey. The gentle blue hills undulate for miles all around, and the tiny green Ema flows merrily below. From the loggia above the little garden one can see the Apennines: the top of the Duomo is just visible, and the grey-green hills above and round it, and Fiesole, dotted with white villas and dark cypresses.

Unattributed.

Certosa of the Val d’ Ema, Cloister in 1878 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

About 2½ miles from the Porta Romana, by the direct road beyond the village of Galuzzo or Bus 37 from stazione Santa Maria Novella, on the hill of Montaguto, is the Certosa del Galluzzo (Certosa of the Val d’ Ema). The position is beautiful, with lovely views, and the convent, with the aspect of a mediaeval fortress, crowning a cypress-crested hill, is very picturesque. The Certosa was founded in 1338 by Niccolò Acciaiuoli (b. 1310), Grand Seneschal and chief adviser to Queen Joanna I. of Naples, and its fortifications were especially granted by the Republic. A small number of Cistercian monks remained here until 2016 when the monastery closed: formerly there were eighty-six.

Niccolò’s father, Acciajuolo Acciajuoli, had undertaken the task of organising the banking-house of the Bardi at Naples in the reign of King Robert the Wise. His uncle, Dardano, more than once held the dignity of Prior, and was twice called upon to fulfil the post of especial ambassador to the King of Naples.

Welbore St. Clair Baddeley, Queen Joanna I. of Naples, p. 146.

The principal Church is over-decorated with frescoes, marbles, and pietre-dure. The pictures relating to the life of S. Bruno are by Poccetti. To the right, through the chapel of S. John Baptist, which has a good picture by Benvenuti, we enter a beautiful gothic church of 1341, of which the architecture is attributed to Orcagna. It contains some good Florentine stained glass; a picture of S. Francis receiving the Stigmata by Cigoli; a Crucifixion by Giotto (?); and a picture by Fra Angelico.

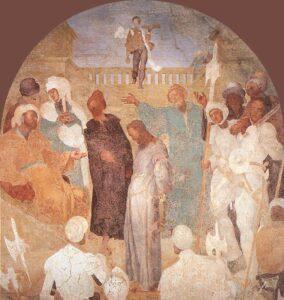

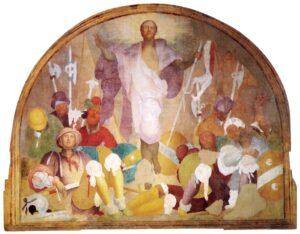

The Palazzo degli Studi contains five much damaged lunettes by Pontormo formerly in the cloister: The Agony in the Garden, Christ before Pilate, The Way to Golgotha, a Pietà, and The Risen Christ. Pontormo had come to the Certosa to escape the plague in 1522 and according to payment records began working shortly after his arrival. At the time Pontormo was much taken with the engravings ofAlbrecht Dürer and adopted a quasi-Germanic style. Approximately 30 years after Pontormo completed the fresci, Jacopo Chimenti, known as Empoli, painted copies, which reveal the coloring of the originals. Empoli’s copies are located at the Certosa.

Jacopo Pontormo, The Way to Golgotha, 1522-25 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Jacopo Pontormo, Resurrection, 1522-25 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Vasari thought that no one could distinguish the “Christ before Pilate” from the work of an ultramontane painter. Such a statement is, of course, an exaggeration, and closer study reveals that Pontormo merely borrowed from Direr, sometimes actually copying them, certain peculiarities of dress, attitude, or contour, and the ragged silhouette and jumbled lineal rhythms of the composition. The draperies, much as Pontormo may have tried to change them, are still Florentine, and the touch, the modelling, and the types, quite Italian. Vasari himself must have noticed Pontormo’s vacillation between northern and southern ideals, for he remarks that, though the most successful fresco, “The Way to Golgotha,” shows throughout Pontormo’s imitation of Dürer, the cupbearer of Pilate in the “Christ before Pilate” still retains a certain something of Jacopo’s earlier manner.

Frederick Mortimer Clapp, Jacopo Carucci Da Pontormo, p. 40.

In the Crypt, before the high-altar, are the exceptionally-preserved tombs of the founder and his family.

Tomb of Niccolò Acciajuolo (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Whether Andrea Orcagna built the Certosa near Florence is uncertain; but the monuments of its founder, Niccolò Acciajuolo, and his family, which exist in the subterranean church, belong to his time, and were perhaps executed by some of his scholars. The tomb of Niccolò (Grand Seneschal of the kingdom of Naples under Queen Joanna I., ob. 1366) consists of his recumbent statue, clad in armour, placed high against the wall, beneath a rich gothic canopy. His son, Lorenzo, upon whose funeral obsequies he spent more than 50,000 gold florins, lies below under a marble slab, upon which is sculptured the effigy of this “youth of a most lovely countenance, cavalier and great baron, tried in arms, and eminent for his graceful manners and his gracious and noble aspect.” Next him lie his grandfather and his sister Lapa.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, p.82.

Boccaccio, in a letter to Zenobio di Strada, lamented Lorenzo’s death, and referred to him as “quello giovane egregio e d’indole ammirevole, Lorenzo, primogenito di questo tuo magno.” [that distinguished and admirable young man, Lorenzo, the eldest son of this great man of yours.] In the same letter he reminds Strada that Niccolò Acciajuoli was wont often to call him Giovanni della Tranquillita.5V. Le Lettere di Giov. Boccaccio.

The general design of Niccolò ‘s tomb is very peculiar, gothic certainly, but almost transitional to the cinquecento. Niccolò, the Grand Seneschal, founder of the convent, was a noble character. The family, originally from Brescia (and named after the trade they rose by), attained sovereignty in the person of Ranier, nephew of the Seneschal, styled Duke of Corinth and Lord of Thebes and Argos and Sparta. He was succeeded by his bastard son Antony, and the latter by two nephews, whom he invited from Florence, Ranion and Antony Acciajuoli; the son of the latter, Francesco, finally yielded Athens to Mahomet II. in 1456, and was soon afterwards strangled by his orders at Thebes.

The Prior I found to be an Irishman, and very agreeably to our wishes undertook to conduct us over his convent. He told us he had been there since 1850. He was dressed in the white habit of the Order of S. Bruno; spoke distinctly but with the always pleasant Irish accent; and paused frequently to ask something political, or historical. He presently took us down to the cold, crypt-like Cappella, wherein lie the remains of the friend of Boccaccio, Queen Joan I., Petrarch, and Zenobio di Strada, even the admirable Niccolò Acciajuoli, of his son, who became hostage for him to King Louis of Hungary, of his sister, Lapa Buondelmonte, the friend of S. Bridget of Sweden, and his father. Very beautiful, and clear cut, and impressive they are! How quiet the five and a half centuries seem down there!

Alexander William Lindsay, Christian Art, vol. ???????

Francesco da Sangallo,

Tomb of Leonardo Buonafede (detail),

1545 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

In a side chapel of the crypt is the tomb of Angelo Acciaiuolo, Bishop of Ostia, 1409,6The family of the Acciaiuoli (Acciajo = steel) fled to Florence from Brescia in 1160 to evade the persecutions of Frederick Barbarossa, and was admitted to the magistracy in 1282. Its most illustrious member was Niccolò) in the XIV c., but endless bishops and archbishops, and three cardinals (Agnolo, Filippo, and Niccolò), were of the same race. by Donatello, with a border of fruit and flowers added by Giuliano di San Gallo. The small cloister is by Brunelleschi, and has some lovely stained glass by Giovanni da Udine. The chapter-house contains a Crucifixion by Mariotto Albertinelli; a Madonna and Child with saints by Perugino; and in the middle of the pavement, in a perfect abandonment of repose, the noble figure of Leonardo Buonafede, Bishop of Cortona, and Superior of this convent (ob. 1545), by Francesco di San Gallo, son of Giuliano.

It is very carefully modelled; the flesh parts are well treated, and the drapery is disposed in natural folds. It has almost the effect of a corpse laid out for burial before the altar, and produces a striking effect.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, p. 254.

The exquisite Della Robbia lunettes of the great cloister were removed to the Accademia in the time of Napoleon I. They had scarcely been restored to the monastery when one side of the beautiful cloister was ruined by the earthquake of 1895.

The Refectory is shown, in which the monks dine on Sundays, released on that day for two hours from their vow of silence, though a reader officiates during dinner from a pulpit in the corner. At the Drogeria, the famous Alkermes and other liqueurs, manufactured in the monastery are sold.

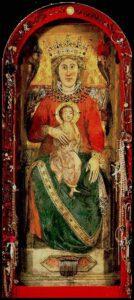

Two and a half miles further, reached by a long but easy ascent, beautifully situated amid the olive-clad hills, is the shrine of La Madonna dell’ Impruneta, one of the most important places of pilgrimage in Tuscany. The church was built in 1593 by Francesco Buondelmonte, and adorned in the seventeenth century by the Confraternita of the Stigmata of S. Francesco with a handsome doric atrium. Here is preserved the image attributed to S. Luke the Evangelist, but which the learned Dr. Lami says was the work of one Luca in the eleventh century, who, on account of his piety, was called saint, whence the tradition. It is said to have been found by a workman buried in the soil of Impruneta, and to have uttered a cry as the spade struck it. On all great occasions of danger, pestilence, or famine, this Madonna has been carried in state by a bare-footed procession to Florence, but even then has always been Veiled—“The Hidden Mother.” Thus it was carried to Florence during the great and terrible plague on April 1, 1400. Over the high-altar is a crucifix by Giovanni da Bologna; and in the Sacristy a curious Madonna and Saints of the School of Giotto. In the nave are pictures by Jacopo da Empoli, Passignano, and Cigoli. The church is backed by Poggio S. Maria, and occupies one side of an immense piazza, decorated with loggias of 1663–70. Here on S. Luke’s Day, October 18, is held the Fair of the Impruneta, for horses, mules, &c., frequented by all the country-folk around, a most picturesque sight. The piazza is the subject of a picture by Callot in the Accademia at Venice.

We must turn to the right from the Porta Romana to ascend the hill of Bellosguardo for the sake of the prospect.

From Tuscan Bellosguardo,

Where Galileo stood at nights to take

The vision of the stars, we have found it hard,

Gazing upon the earth and heavens, to make

A choice of beauty.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Casa Guidi Windows, Part 1:30.

At the foot of the hill is the Church of S. Francesco di Paola.

Most lovely is the view from the summit of the hill, especially from the terrace of the principal villa—Michelozzo—which has a fine old tower of Medici date; though long previously the father of Guido Cavalcanti, the poet, owned it; and it remained Cavalcanti property until 1447, when Tommaso Capponi bought it.

I found a house, at Florence, on the hill

Of Bellosguardo. ‘Tis a tower that keeps

A post of double observation o’er

The valley of the Arno (holding as a hand

The outspread city) straight towards Fiesole

And Mount Morello and the setting sun,

The Vallombrosan mountains to the right,

Which sunrise fills as full of crystal cups

Wine-filled, and red to the brim because it’s red.

No sun could die, nor yet be born, unseen

By dwellers at my villa; morn and eve

Were magnified before us in the pure

Illimitable space and pause of sky,

Intense as angels’ garments blanched with God,

Less blue than radiant. From the outer wall

Of the garden, dropped the mystic floating grey

Of olive trees (with interruptions green

From maize and vine) until ‘twas caught and torn

On that abrupt black line of cypresses

Which signed the way to Florence. Beautiful

The city lay along the ample vale,

Cathedral, tower and palace, piazza and street;

The river trailing like a silver cord

Through all, and curling loosely, both before

And after, over the whole stretch of land

Sown whitely up and down its opposite slopes

With farms and villas.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Aurora Leigh, p. 293.

The scenery of the hills behind Bellosguardo is known to have suggested that of Monte Beni, so beautifully described in “Transformation.”7Also known as The Marble Faun.

The Umbrian valley opens before us, set in its grand framework of nearer and more distant hills. It seems as if all Italy lay under our eyes in this one picture. For there is the broad, sunny smile of God, which we fancy to be spread over this favoured land more abundantly than on other regions, and beneath it glows a most rich and varied fertility. The trim vineyards are there, and the fig-trees, and the mulberries, and the smoky-hued tracts of the olive-orchards; there, too, are fields of every kind of grain, among which waves the Indian-corn. White villas, grey convents, church spires, villages, towns, each with its battlemented walls and towered gateway, are scattered upon this spacious map; a river gleams across it; and the lakes open their blue eyes in its face, reflecting heaven lest mortals should forget that better land, when they behold the earth so beautiful.

What makes the valley look still wider is the two or three varieties of weather often visible on its surface, all at the same instant of time. Here lies the quiet sunshine: there fall the great patches of ominous shadow from the clouds: and behind them, like a giant of league-long strides, comes hurrying the thunderstorm, which has already swept midway across the plain. In the rear of the approaching tempest brightens forth again the sunny splendour, which its progress has darkened with so terrible a [frown].

All around this majestic landscape, the bald-peaked or forest-crowned mountains descend boldly upon the plain. On many of their spurs and midway declivities, and even on their summits, stands cities, some of them famous of old; for these have been the seats and nurseries of early Art, where the flower of Beauty has sprung out of a rocky soil, and in a high, keen atmosphere, when the richest and most sheltered gardens failed to nourish it.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, Transformation, vol. 2, pp. 195–97.

Adjoining is the Villa Ombrellino, where for sixteen years lived Galileo; and here he composed the Dialogue discussing the Ptolemaic and the Copernican systems. All learned Florentines, and every foreigner of distinction, breasted the steep hill of Bellosguardo to listen to the wonderful conversation of Galileo. Eloquent, sarcastic, brimming over with fun and humour, yet full of learning, he was a delightful companion. He was only happy in the country, declaring cities to be the prisons of human intellect.

Janet Ross, Florentine Villas, p. 62.

The villa where Milton found him, however, was at Arcetri.

On a spur of the hill to the north of the wooded height of Bellosguardo is the Convent of Monte Oliveto, containing in its Refectory an annunciation of Domenico Ghirlandajo.8In 1869, two years after the painting was transferred to the Uffizi, Baron Liphart identified the Annunciation as an early work of Leonardo da Vinci. Most experts agree. Hence one may descend to the iron bridge which leads to the Cascine.

Porta San Frediano (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

From the Porta S. Frediano (La Badia di Settimo, Signa, Malmantile Artemino).

This side of Florence is less well known than the others, but by no means less interesting. The road—Via Pisana—runs through the Pianura di Ripoli, an exquisitely rich and fertile valley, and there is a tramway by which Lastra a Signa may be reached in one hour from the Piazza Castello at Florence (fare 1st cl. 70 c., 2nd cl. 50 c.). On the right of the valley is a beautiful chain of mountains, of which the principal is Monte Morello, which serves as a weather-gauge to the whole countryside, according to the old proverb:

Quando monte Morello ha il cappello,

Villan, prendi il mantello.9When Monte Morello has a hat, / Countryman, take a cloak.

Just before reaching Legnaja, a road turns off (left) to Scandici, abounding in nightingales, where the Villa Passerini occupies the site of an ancient castle of the Bagnesi, and the excursion may be continued to S. Paolo and to S. Andrea a Mosciano and the remains of a castle of the Acciaiuoli.)

From La Casellina on the Via Pisana a side road leads (left) to the picturesquely-situated XIII. c. church of S. Martino alla Palma, with a wide-spreading portico. There are enchanting views from this spot, and though the hill (159 met.) is steep, the drive to S. Martino is one of the most beautiful near Florence.

Four and a half miles from Florence, at half a mile to the right of the road near the village of S. Colombano, is the old Cistercian Convent of La Badia a Settimo, now a private villa. Founded by a Conte di Borgomuro, about 984, it has noble machicolated walls and a fine old gateway of a later period, the front of which is decorated with a figure of Christ enthroned between two saints, one of the largest works in terra-cotta in Tuscany—built, not let into the wall. The beautiful campanile, after the model of S. Niccolò at Pisa, is attributed to Niccolò Pisano. In the church are a Robbia frieze and a rich altar of pietradura. An Aumbrey is attributed to Desiderio da Settignano. Some pictures by pupils of Verocchio and Ghirlandajo were removed in 1884, and are now in the museum at S. Apollonia.

In Lent 1670, 8000 persons collected here to witness the trial by fire, in which the Vallombrosan monk Pietro Aldobrandini (afterwards canonised as S. Pietro Igneo) walked barefooted, unhurt, through a furnace, to prove an accusation of simony brought by S. Giovanni Gualberto against Pietro di Pavia, Bishop of Florence.

On the left of the road are Castel Pulci10Reflecting the views of a time past, St. Clair Baddeley observed that the Castel was “now a lunatic asylum” in 1925 and the charming old Villa of Castagnolo, once the property of the Arte della Lana, but in 1210 bought by a Della Stufa, who belonged to the Arte della Tela. Of this family were the Beato Girolamo of the Minori Osservanti di S. Francesco and the Beato Lottaringo, one of the seven founders of the SS. Annunziata. Many points on the hills behind Castagnolo are full of picturesque interest.

Lastra a Signa City Wall (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Half a mile farther is the interesting old town of Lastra a Signa, preserving intact its machicolated mediaeval walls and its three gateways. It contains many picturesque architectural fragments, especially a vaulted and frescoed loggia, very rich in colour, above which is the modern theatre. Signa is well worth a visit by those who stay long in Florence, and may be reached by railway as well as by tram. Its population was once entirely employed in the plaiting of straw hats—cappelli di paglia.

The hills lie quiet and know no change; the winds wander amongst the white arbutus-bells and shake the odours from the clustering herbs; the stone-pines scent the storm; the plain outspreads its golden glory to the morning light; the sweet chimes ring; the days glide on; the splendours of the sunset burn across the sky, and make the mountains as the jewelled thrones of the gods. Signa, hoary and old, stands there unchanged—Signa is wise. She lets this world go by, and sleeps.

Ouida, Signa, vol. 3, pp. 373–74.

Two and a half miles from Signa, by a steep ascent is the curious fortified village of Malmantile. The road thither, beneath the old convent of S. Lucia, through a mountain gorge, is lovely, and the place itself, on the wild hill-top, is striking, being so strongly fortified, yet so small. It long resisted a siege by the Florentines, which is the subject of the curious poems “L’Assedio” and “La Scacciata di Malmantile,” written by Lippo Lippi early in the seventeenth century. The walls now enclose only a single street of cottages.

View of the Malmantile wall and countryside from the North-East (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The lovely effects of the morning mist in this enchanting district are happily described by Ouida.

There had been heavy rains at night, and there was, when the sun rose, everywhere that white fog of the Valdarno country which is like a silvery cloud hanging over all the earth. It spreads everywhere and blends together land and sky; but it has breaks of exquisite transparencies, through which the gold of the sunbeams shines, and the rose of the dawn blushes, and the summits of the hills gleam here and there with a white monastery, or a mountain belfry, or a cluster of cypresses seen through it, hung in the air, as it were, and framed like pictures in the silvery mist.

It is no noxious steam rising from the rivers and the rains; no grey and oppressive obliteration of the face of the world like the fogs of the North; no weight on the lungs and blindness to the eyes; no burden of leaden damp lying heavy on the soil and on the spirits; no wall built up between the sun and man; but a fog that is as beautiful as the full moonlight is—nay, more beautiful, for it has beams of warmth, glories of colour, glimpses of landscape such as the moon would coldly kill; and the bells ring, and the sheep bleat, and the birds sing underneath its shadow; and the sun-rays come through it, darted like angels’ spears; and it has in it all the promise of the morning, and all the sounds of the waking day.

Ouida, Signa, vol. 3, pp. 67–68.

Three miles beyond Signa is the delightful Medici villa of Artemino (“Ferdinanda”), with exceptional views toward Florence. In this neighbourhood also, much nearer Signa, is the noble villa of Le Selye (Buontalenti), which belonged to Filippo Strozzi, who married the famous Clarice, daughter of Pietro de’ Medici. Afterwards the villa belonged to the Salviati. It was from one of its beautiful loggias that Galileo observed the ring of Saturn and the sun-spots. Close by is an old monastery, with the chapel where S. Andrea Corsini said his first mass. The lower hills are covered with vineyards, producing the celebrated wine of which Redi sings:

La rugiada di Rubino,

Che in Valdarno i colli onora,

Tanto odora,

Che per lei suo pregio perde

La brunetta

Mammoletta,

Quando spunta dal suo verde.

The ruby dew that stills

Upon Valdarno’s hills

Touches the sense with odour so divine,

That not the violet,

With lips with morning wet

Utters such sweetness from her little shrine.

Francesco Redi, Bacchus in Tuscany, p. 36. Trans. Leigh Hunt.

Porta al Prato today (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Fabio Borbottoni (1820-1902), Porta al Prato and city walls (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

From the Porta al Prato (Poggio a Cajano, Petraja, Castello).

Beyond the Barriera di S. Donato and behind the Cascine, is (at about 1 mile) the Villa S. Donato, built in the early part of the XIX. c., on the site of an old Augustinian monastery, by the Russian Count Nicholas Demidoff, who, in recognition of his magnificent charities, received the title of Principe di San Donato from the Grand-Duke. His son Anatole married the Princess Mathilde Bonaparte. The vast collections of works of art, with which the villa was filled, were sold by Prince Paul Demidoff.

A road which passes (left) the Villa Panciatichi, with the old tower of the Agli, its owners in the XIV. c., and (left) the church of S. Cristofano a Nuvoli, with a colossal fresco of S. Christopher in its portico, leads to Peretola, where Florentine burghers had their jousting-field in the XIII. c., and where pink lilies of the valley may be found in spring. The Villa Petrucci Bargagli occupies the site of an old castle of the Spini.

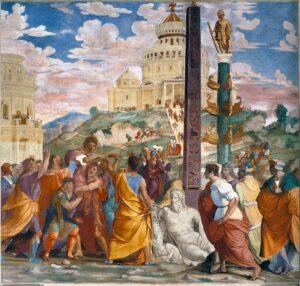

Giuliano da San Gallo, Poggio a Caiano (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

From Peretola a dull road (tram from the Piazza S. Maria Novella, a branch from that to Prato) to the left leads (about 10 miles from Florence) to the imposing Villa of Poggio a Cajano, which was built by Giuliano di San Gallo for Lorenzo the Magnificent, and became one of his favourite retreats. Hither Lorenzo came frequently for the sake of his favourite amusement of hawking, accompanied by Pulci, who cared little for the diversion. “La Caccia con Falcone” [The hunter with falcon] describes him as missing, and having hidden himself in a wood to make poetry. He planted an islet in the Ombrone, flowing below, with many rare flowers.

The vault of the great saloon was considered by Vasari to be the largest of modern times. It was painted by order of Leo X. with frescoes by the great masters of the period, intended as allegorical of the glories of the Medici, viz.:—

Pontormo. The Banquet given to Scipio by Syphax—typical of the banquet given to Lorenzo by the King of Naples.

Pontormo. Titus Flaminius Rejecting the Ambassadors of Antiochus—typical of Lorenzo annihilating the plans of Venice in the Diet of Cremona.

The lunette is described by Mr. Berenson as “the most appropriate mural decoration now remaining in Italy.”

The rooms (with little of the original furniture remaining) are to be seen in which the Grand-Duke Francesco I. died, October 19, 1587, and on the following day his wife, the beautiful Bianca Cappello. The story of Bianca is a typical romance. Daughter of a proud Venetian noble, Bartolommeo Cappello, she eloped with Pietro Bonaventuri, a young Florentine, by whom she was already with child, and she was married to him at his mother’s house in the Piazza S. Marco at Florence. Here she attracted the favour of Francesco de’ Medici, eldest son of Duke Cosimo, and he made her his mistress. Bonaventuri was shortly after murdered by bravoes in the employment of the Ricci, with a daughter of whose house he had intrigued. After the accession of Francesco to the throne, and the death of his duchess, Giovanna of Austria, Bianca was married to the Grand-Duke in the Palazzo Vecchio, June 5, 1578, and enjoyed her dearly bought honours for eight years, until she perished with her husband, under strong suspicions of poison, during a visit of the Grand-Duke’s brother and successor, Ferdinando, who had always been the bitterest enemy of Bianca. Francesco was buried with all pomp in the family mausoleum at S. Lorenzo, but Bianca, wrapped in a sheet; was thrown into the common grave for the poor, under the nave of the same church.

There, at Cajano,

Where when the hawks were mewed and evening came,

Pulci would set the table in a roar

With his wild lay—there, where the sun descends,

And hill and dale are lost, veiled with his beams,

The fair Venetian died, she and her lord —

Died of a posset drugged by him who sate

And saw them suffer, flinging back the charge,

The murderer on the murdered.

Samuel Rogers, Italy: A Poem.

It has an external staircase up which horses can go.

The low-lying Park, with its ugly rows of poplars, damp shrubberies and summer-houses on the Ombrone, is greatly admired by the Florentines, but will not be thought worth a visit by foreigners, though there is an old proverb which says

Val più una lastra di Poggio a Cajano

Che tutte le bellezze d’Artemino.

A paving stone of Poggio a Cajano is worth more

Then all the Beauties of Artemino.11Reference to “La Ferdinanda,” the Medici Villa at Artemino.

A breed of buffaloes, afterwards common in Italy, was first introduced at Poggio a Cajano by Lorenzo de’ Medici.

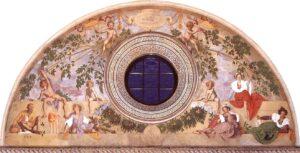

About four miles from the Porta al Prato (most easily reached by bus 28 from Firenze Hub Montelungo near stazione S. Maria Novella, or by rail, the station of Castello being close by) is the charming royal Villa of Petraja, once belonging to Palla Strozzi. It was adorned by Buontalenti. One tower only remains of the castle of the Brunelleschi, its ancient owners, who triumphantly defended it in 1364 against the Pisans and English under Sir J. Hawkwood, then fighting against Florence. The gardens, on the southern slope of the Apennines, are most lovely. A fountain by Tribolo is surmounted by a Venus of Giovanni da Bologna: it is pronounced by Vasari to be “the most beautiful of all fountains.” The loggie are adorned with frescoes by Il Volterrano. Here Scipione Ammirato, under the eyes of Cosimo and his son Ferdinando, wrote that history of Florence which procured him the name of the New Livy. The gardens have not improved since the palace was occupied by Madame (“la bella Rosina”) Mirafiore.

High in the hill above Petraja sits the royal villa of La Topaja, which Cosimo I. gave as a residence to Benedetto Varchi, who wrote his history there, and during his lifetime called the villa Cosmiano, in honour of his patron.

The lower slope of the hills beneath Petraja is clothed by the lovely woods and gardens of the famous Medicean (now royal) villa of Castello (formerly Il Vivaio), bought from the Della Stufa by Lorenzo di Pier Francesco de’ Medici in 1477, and ever after a favourite residence of his family. Its gardens were decorated by Tribolo for Cosimo I., who died here of a malignant fever, April 1, 1574. It is situated just above the main road. The central fountain in the gardens has a group of Hercules and Antaeus by Ammannati. A smaller fountain is attributed to Donatello. Walks and drives ascend through woods of flowering shrubs to an upper terrace whence there is an exquisite view of the plain, its tender green and grey broken by dark spires of cypresses, and backed by ranges of pale violet mountains. The little church of S. Michele and its cypresses forms a picturesque feature between Castello and Petraja. Here lived Caterina Sforza during the last seven years of her dramatic life with her son Giovanni delle Bande Nere, not without bitter anxieties. Ferdinand III. gave it several pictures, since removed to the National Collections: a picture by Cigoli and a crucifix by G. da Bologna are still in the church. The Jesuit father, Jacopo Cortese, better known as Borgognone (not Ambrogio), the battle-painter, was a native of Castello.

Nearby is the Villa L’Ulivaccio, formerly belonging to the Gondi family; Ponte a Rifredi, named from a bridge over the torrent Terzolle; S. Stefano in Pane, where the church, which contains some good pictures, bears the arms of the Tornabuoni family, its former owners; the Villa Guicciardini, now a distillery; and Il Sodo, an old house with a tower, which belonged to the Strozzi.

The Via di Castello leads to the palace, passing the gates of the Villa Corsini or Il Lepre dei Rinieri, an imposing edifice by Antonio Ferri, the principal architect of the Corsini palace at Florence. In 1460 the property was purchased from the Strozzi by the Rinieri, whose name it long bore. There is a noble old garden and cypress avenue. An inscription on the front of the palace records the residence and death there, in 1649, of Robert Dudley, son of Queen Elizabeth’s Earl of Leicester, famous for his travels and inventions. In his latter years he settled at Florence, where his ingenuity as a shipbuilder and mathematician attracted the notice of Cosimo II., whose wife, the Grand-Duchess Maddalena, made him her chamberlain. Her brother, the Emperor Ferdinand II., created him Earl of Warwick and Duke of Northumberland in the Holy Roman Empire, in 1620. He was employed by Cosimo II. in draining the marshes between Pisa and the sea, to which Leghorn owes its prosperity. He wrote here his famous naval work, Dell’ Arcano del Mare di D. Roberto Dudleo, Duca di Northumbria e Conte de Warwick, 1646–7. Dying in his villa, he was buried in the little neighbouring monastery of S. Giovanni Evangelista at Boldrone, where Giuliano Ricci, the learned nephew of Macchiavelli, was also buried in 1574. He left seven daughters and five sons by his wife Alice Leigh,12Of the Leighs of Stoneleigh. whom he had long deserted.

Near Castello, on the outskirts of the hills, is the beautiful villa of Quarto, which belonged to the Grand-Duchess Marie of Russia. On the Via di Serezzano is the Villa Le Bracche or Bellagio, which belonged to the beautiful Camilla Martelli, who became the second wife of Cosimo 1. Their daughter Virginia, Duchess of Este, inherited the villa from her mother.