5.3: The North-Western Quarter: Palazzo Strozzi, Santa Maria Novella and Vicinity

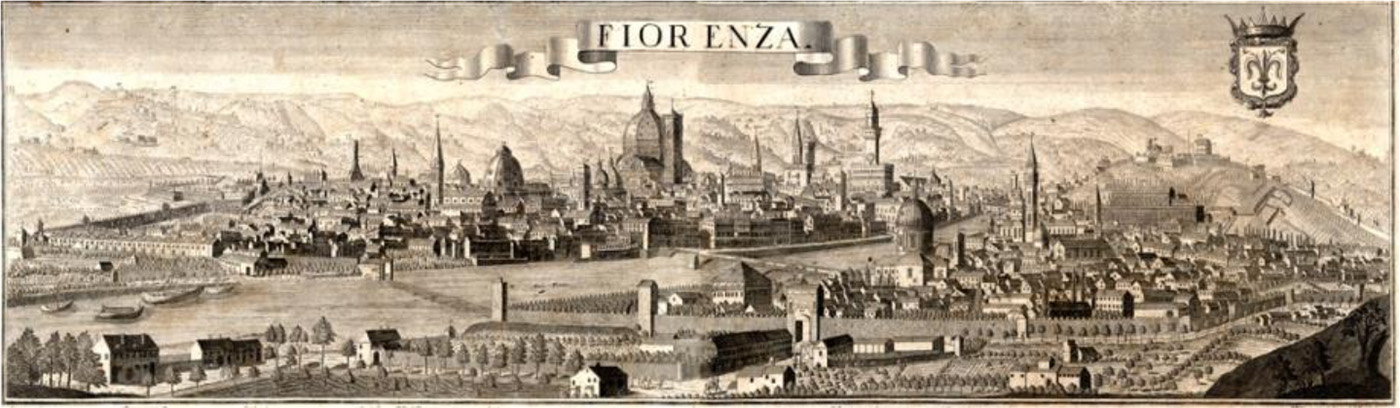

THE Via Tornabuoni, named from the great family of which a daughter, Camilla Lucrezia, was the mother of Lorenzo the Magnificent, is the gayest and handsomest street in Florence, where the best clubs and cafes are, and where the most beautiful flowers are sold at the street corners.

Via Tornabuoni is charming, and merits to be observed for the ensemble it offers of the contemporary Florentine expression, with its alluring shops, its confectioners and cafés, its florists and milliners, its dandies and tourists, and, ruggedly massing up out of their midst, the mighty bulk of the old Strozzi Palace, mediaeval, sombre, superb, tremendously impressive of the days when really a man’s house was his castle. Everywhere in Florence the same sort of contrast presents itself in some degree, but nowhere quite so dramatically as here.

W. D. Howells, Tuscan Cities, p. 22.

Ascending the street, we pass (Nos. 10–14) the Palazzo Altoviti-Sangalletti,1Arms of Altoviti: sable, a wolf rampant argent. due to Silvestri. No. 5, opposite, the Palazzo Giaconi, was built by Giovan. Battista Strozzi in the XVII. c. No. 12 has an open loggia at top and brown walls. No. 3 was formerly the Hôtel Nord; it has a stone cornice, and over the principal door: Carpere promptius quam impar. [It is easier to criticize than to imitate.] It is enriched also with four round-headed medallions between the window-heads. The shield bears a lion rampant.

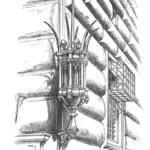

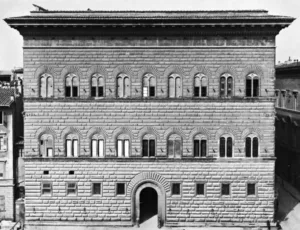

Benedetto da Maiano, Strozzi Palace (photo Britannica)

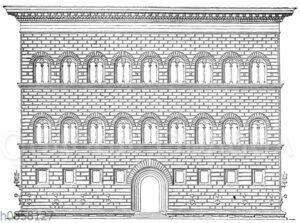

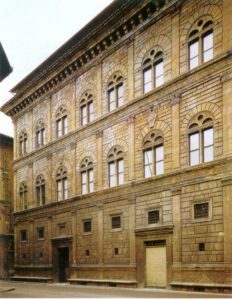

Then we reach, on the right, the magnificent Palazzo Strozzi, begun in 1489 for the merchant Filippo Strozzi, from designs of Benedetto da Majano, which were continued by Il Cronaca. The palace, deriving from the Riccardi, its predecessor, is faced with gigantic blocks of rough-hewn stone, which, instead of detracting from, gives, by contrast, an appearance of extra finish to the details, and an effect at once massive and tranquil to the whole. At the corners are beautiful specimens by Niccolò Caparra of the iron fanali, which were only allowed to the most distinguished citizens. The magnificent cornice corner of the Strozzi palace has egg and dart above dentil moulding.

The flowers they sell on the stone bench round its old wall, underneath the huge irons in which flags have flaunted and torches burned for hundreds of years on triumphal occasions the sheaves of lily of the valley, white lilac, white narcissus, already abundant and scenting all the air in the first cold days of April—seem scarcely more evanescent than the crowd of men and women who have bloomed and passed and gone into darkness while the old wall has stood fast, without getting so much as a wrinkle or line chiselled by age upon its rugged stones.

“Two Cities—Two Books,” Blackwood, DCCV, pp. 75–76.

Perhaps the most satisfactory of the Florentine palaces, as a whole and complete design, is the Strozzi, designed by Cronaca (1454–1509). It is a rectangle, 190 feet by 138; like all the rest, in three stories, measuring together upwards of 100 feet in height. The cornice that crowns the whole is not so well designed as that of the Riccardi, but extremely well proportioned to the bold simple building which it crowns, and the windows of the two upper stories are elegant in design, and appropriate to their situation. It may be that this palace is too massive and too gloomy for imitation; but, taking into account the age when it was built, and the necessity of security combined with purposes of state to which it was to be applied, it will be difficult to find a more faultless design in any city of modern Europe, or one which combines so harmoniously local and social characteristics with the elegance of classical details, a conjunction which has been practically the aim of almost every building of modern times, but very seldom so successfully attained as in this example.

James Fergusson, History…Modern Styles of Architecture, pp. 85–86.

The preparations for the building of this Casa Grande were made with great caution, lest it should seem that a work too magnificent for a private citizen was being undertaken: in particular, Filippo so contrived that the costly opus rusticum employed in the construction of the basement should appear to have been forced upon him. This is characteristic of Florence in the days of Cosimo. The foundation-stone was laid in the morning of August 16, 1489, at the moment when the sun arose above the summits of the Casentino. The hour, prescribed by astrologers as propitious, had been settled by the horoscope; masses meanwhile were said in several churches, and alms distributed.

J.A. Symonds, Renaissance in Italy: The Fine Arts, pp. 55–56.

The palaces of its best families are built like fortresses: without are still seen the iron rings, to which the standards of each party were attached. All things seem to have been more arranged for the support of individual powers, than for their union in a common cause. The city appears formed for civil war.

Madame de Staël, Corinne, p. 338.

The interior of the palace is a handsome specimen of a noble Florentine residence. The best of the beautiful objects it once contained have been dispersed,2The 9th edition notes that “These are no longer shown, and probably are dispersed.”

1st Room: Mino da Fiesole. Bust of Niccolò Strozzi, Donatello. Statuette of S. J. Baptist—absurdly old for one who must have died at thirty-two, Filippino Lippi. The Annunciation.

2nd Room: *Leonardo da Vinci. (?) A beautiful portrait of a Strozzi lady, in a black dress and pearl necklace, holding a book—the background green, Pollajuolo. Portrait of the murdered Giuliano de’ Medici, taken after death, Sustermanns. Giov. Batt. Strozzi, with his wife (a Martelli) and children, Andrea del Sarto. Small Holy Family, Perugino. The Garden of Gethsemane—very beautiful, but the angel unnecessarily supported by a little island in the sky.

3rd Room: Benedetto da Majano. Bust of Filippo Strozzi the Elder,, Copy of a Titian at Vienna, Portrait of Filippo Strozzi the Younger, Alessandro Allori. Portraits of Piero, Roberto (father of the Puttina), and Leone Strozzi, sons of Filippo, Lorenzo di Credi (over entrance-door). Holy Family, Perugino (over farther door). Holy Family.

4th Room: Salvator Rosa. Two Landscapes, *Ang. Bronzino. Portrait of Cardinal Bembo when young, *Raffaelle. Portrait of the poet Ludovico Martelli, P.Veronese. Portrait of Pope Paul III., Caravaggio. Gamblers. including the noble bust of Marietta Palla Strozzi by Desiderio da Settignano, and the portrait of the daughter of Roberto Strozzi (“La Puttina” [the little whore]) painted by Titian and extolled by Aretino. Both of these treasures are now at Berlin. The still important family descend from Ubertino Strozzi of the XIII. c., and has produced sixteen gonfalonieri and ninety-four priori. It was Filippo di Matteo, the builder of the palace, who is reputed to have introduced the artichoke and “fico gentile” [type of fig] into Tuscany.3Arms: or, on a fess, gules, three crescents, argent.

The palace piano nobile is now utilized as a temporary exhibition venue—the largest such space in Florence.

Perhaps the most admired façade of the palace is that which looks down on the Piazza dei Strozzi. Here also stands the Palazzo Strozzino, a more ancient palace of the Strozzi family, built c. 1460 by Michelozzo for Palla Strozzi. In the 1920s Marcello Piacentini built the Odeon cinema, one of the very few examples of the Art Deco style in Florence, in the courtyard. Near it is the little church of S. Maria degli Ughi, built originally in the VII. c. The bell of this oratory, due to Niccolò Caparra, formerly rang the curfew at sunset.

On the left (opposite the Strozzi Palace) opens the Via Vigna Nuova, where No. 2, which had belonged to the Rucellai, was the residence of Robert Dudley, son of Queen Elizabeth’s Earl of Leicester and Amy Robsart (?), who left England for ever because his title as Earl was not recognised owing to the uncertainty about his mother’s marriage. Kindly welcomed by Cosimo II., he was created Duke of Northumberland by the Grand Duke’s brother-in-law, the German Emperor. His engineering genius was of service to the State of Florence, for which he built the mole of Leghorn. He was the author of many works, of which the Arcanum Maris was the most celebrated. Dying in 1640, he was buried by the side of his wife (1637) in the neighbouring church of S. Pancrazio. On the graceful XV. c. architrave of No. 10 are the arms of the Minerbetti.

No. 20 is the Palazzo Rucellai, with flat pilasters carried through three storeys, built for Giovanni Rucellai—“delle fabbriche”—by Bern. Rossellino, c. 1451, but from designs of Leon Battista Alberti, to whom the beautiful loggia of the Rucellai opposite is also due. Its appearance as well as style will recall to the visitor the yet more perfect Palazzo Giraud-Torlonia by Bramante at Rome, which felt its direct influence. It was beneath this loggia, now closed, that Bernardo Rucellai was married to one of the Medici. The courtyard of the palace has admirable Corinthian pillars, and it contains many curious old portraits. The Rucellai descend from the merchant Alamanno, who brought the orchel (Erba orcella), largely used in dyeing wool, to Florence from the East, and made a great fortune.4Arms: Per bend gules, a lion rampant argent, five bars dancetty azure, or. Of his descendants were the patriotic and popular Bencivenni, called Cenni, of whom, when the Republic was in danger, the people were wont to say, “God and Cenni will provide”; Paolo Rucellai, the naval victor over the Genoese at Rapallo; Giovanni, to whom Florence owes the façade of S. Maria Novella and many other fine buildings; Bernardo, the historian whom Erasmus compares to Sallust; his son Cosimo, the poet-founder of the Platonic Academy; another son, Giovanni, the author of Rosmunda; and Giulio, the ecclesiastical reformer of the XVIII. c. In the Via della Spada behind is the Cappella Rucellai built by Giovanni, and containing a model of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem, by Alberti.

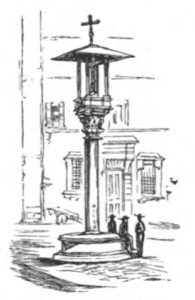

From this street turns off westward the Via delle Belle Donne, “a name,” says Leigh Hunt, “which is a sort of tune to pronounce.” It leads direct to the little piazza Croce al Trebbio (Trivium),5Trivium indicates the place where three roads intersect. a memorable spot in Dominican annals, where Pietro Martire had been ordered to Florence to assist the Prior of S. Maria Novella in subduing the heretical Cathari, whose formidable numbers were helped by the protection of the Ghibelline nobles, such as the Cavalcanti, Pulci, Baroni, and Cipriani. Ruggieri the Prior called in to his aid the Priori of the Guilds, and the Pope (Innocent IV.) wrote to the Signoria urging its co-operation. The Piazza, of S. Maria Novella had to be enlarged in order to accommodate the multitudes who came to hear Pietro and see the burnings at the stake therein. The fanaticism of the Inquisitors robbed them of the favour of the Signoria, and two sanguinary battles were fought between them with their adherents and the heretics with their defenders, one in Piazza S. Felicità, and the other here. Pietro himself led his followers, holding a standard, and the victory was his in both places (1245, S. Bartholomew’s day). The Croce al Trebbio consists of a column on a pedestal, which originally bore a statue of S. Peter Martyr, but now sustains a crucifix.

Giovanni Antonio Dosio, Palazzo Larderel, 1580 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Giovanni Battista Foggini, Palazzo Viviani della Robbia, 1693 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

No. 20 Via Tornabuoni is the Palazzo Corsi Salviati (formerly Tornabuoni), attributed to Michelozzo, but modernised in 1867. No. 15 is the Baroque style Palazzo Viviani, No. 19 the Palazzo Larderei, built by Dosio for one of the Giacomini family, and admirable for its architectural simplicity.

Pier Francesco Silvani, San Gaetano façade, begun 1643 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Church of S. Gaetano,6Formerly S. Michele Berteldi, from the owners of a neighbouring palace; then S. Michele dei Diavoli, from a figure of S. Michael. The Theatines, who rebuilt the church, dedicated it to their founder. with a rich Baroque façade, contains a beautiful crucifix given by Lorenzo, son of Ferdinand I., and, in the right transept, the tombs of Cardinal Bonsi and several of his family, patrons of the church. It is a gloomy interior, but is nevertheless rich in effect, having six side chapels adorned with much marble and large pictures. There are also many statues in niches above these. In the Sacristy is a Virgin and Child by Della Robbia. Facing it is the Palazzo Antinori, built by Giuliano di S. Gallo. The illustrious family of the Antinori7Arms of Antinori: Per fesse a chief, lozengy, or and azure, and or. descend from the Buondelmonti.

Hence the Via Rondinelli leads north immediately to the Via Cerretani (named from an illustrious family now extinct) and left to the Via dei Banchi. [Via dei Banchi, the former quarters of the Ginori family.8Arms of Ginori: azure, on a bend or, three stars azure. No. 6 is a palace formerly belonging to the Cini. (It now carries a shield with a barry of six, and over all, a lion rampant.) The cupola of the Duomo is seen beyond. In order to reach San Lorenzo we cross the Via dei Panzani and take Via del Giglio. No. 9 has a shield semée fleur-de-lis, and on a bend sprays of olive; and we gain Piazza Madonna degli Aldobrandini and the Medici Chapel, with its red dome, and altogether ugly. The palace opposite it on our left, No. 5, has a bust over the entrance and a sgraffito front with the arms of Della Stufa. Above, it has an open loggia. Turning down the latter (left) we reach the Piazza di S. Maria Novella.

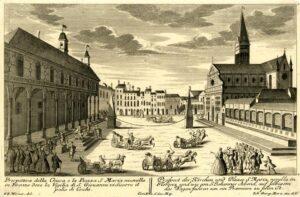

Friedrich Bernhard Werner (after), Coach races in Piazza Santa Maria Novella, 1735 (photo British Museum)

In 1563, Cosimo I. introduced chariot-races here, in which the existing obelisks served as the goals: they rest on tortoises, and are surmounted with lilies by Giovanni da Bologna.

Filippo Brunelleschi (after), Loggia, Ospedale di San Paolo, begun 1451 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The arcade facing the S. Maria belongs to the Hospital of S. Paolo, today the home of the Museo Novecento, the museum of 20th-century art. It is adorned with medallions of Luca and Andrea della Robbia: the two at the ends are portraits of the artists themselves. A relief over a door, at the end within the arcade, commemorates a meeting between S. Francis and S. Dominic, which is said to have taken place on this spot.

Church of the Vanchetone (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The neighbouring Church of the Vanchetone (in the Via del Palazzuolo just behind) is so called from the character of the Confraternity which possessed it—Vanno chetone—they go on in silence. It contains a black image of the Madonna, given by the Medici, two busts of boys by Donatello, on either side the sacristy, and the skeleton of Ippolito Galantini, a member of the Order.

It was from No. 21 in the piazza of S. Maria, which was the residence of Luca Pitti before he built his palace, that Garibaldi addressed the people, before his futile expedition against Rome, with the impressive words: “O Roma, O Morte.” The Hôtel de Rome was formerly the Palazzo Libri, belonging to an illustrious family which came to Florence from Valdarno in the XIV. c.

Santa Maria Novella, begun 1278, Façade (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The great Dominican Church of S. Maria Novella was begun 1278 at the expense of the Rucellai, on the site of an earlier church called S. Maria tra le Vigne, at that date beyond the walls. It is the fashionable church in Boccaccio’s “Il Decamerone.” Completed in seventy years, from its beauty it was called by Michelangelo La Sposa, or the bride. The façade of the church, of white and green marble and serpentine, was not finished till 1470.9Hare’s observation that the façade “has been so toned and mellowed by weather that its geometrical effects are no longer aggressive” is no longer true. On the lower level, the central doorway, lateral columns, and pilasters are by Leon Battista Alberti; the side doorways, Gothic niches containing tombs, arches above them, and the giant oculus are of earlier date. Over the doors are frescoes by Ulisse Ciocchi. The upper level, by Alberti, resembles a temple front topped with a triangular pediment in the centre of which is the Dominican’s radiant sun. The massive, richly decorated volutes unify the upper and lower portions of the façade. On the right is a small cloister by Brunelleschi, surrounded by pointed arches containing tombs, each panelled in with three slabs, having a varying cross between two shields of arms. The obelisk in front is of Fiore de Persico, an ancient marble, and rests on four bronze turtles (a Medici symbol) by Giovanni da Bologna.

Santa Maria Novella, Nave (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

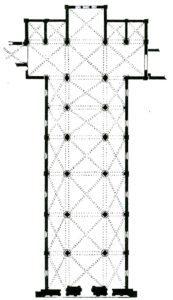

Within, the church presents the form of a Latin cross, and consists of nave and aisles of six bays, having round lights over the crown of each arch of the nave, for clear-storey; and in the walls of the aisles single lancet-lights, beneath each of which is an altar.

The West wall (really south) contains a large stained window formed in three concentric circles.

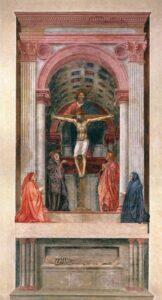

The fine fifteenth-century paintings have been “restored” to their destruction. Over the entrance is a crucifix, perhaps by Puccio Capanna, a pupil of Giotto. On our right is a fresco of the Trinity, with the Virgin and S. John, and kneeling donors, by rare Masaccio. On the left is the Annunciation.

Proceeding round the church from the right, we have—

1st Altar, R. Aisle. Girolamo Macchietti. The Martyrdom of S. Lorenzo. The four succeeding altars have pictures by Gio. Batt. Naldini, a pupil of Bronzino. On either side of the altar dedicated to S. Thomas à Becket are two fifteenth-century monuments of the Minerbetti family, who claimed kindred with the saint. Over the last altar in this aisle is a picture by Jacopo Ligozzi (1543–1627), representing the resuscitation of a dead child by S. Raymond of Peñaforte. Close by is the tomb, by Romolo di Taddeo da Fiesole, of Giov. Batt. Ricasoli, Bishop of Cortona, the trusted counsellor of Cosimo I. He was sent to France in 1557, charged to poison the Grand-Duke’s enemy, Piero Strozzi, but was forced to fly with the deed unfulfilled, and was henceforth known as the “Vescovo dell Ampollina,” the Bishop of the Poison-cup. He died in 1572.

The Transepts have terminal chapels; and the choir is flanked on each side by two chapels. The High-altar, raised on a five-step dais, is of black and white marble, and throws up very richly the magnificent three-light stained windows behind it.

Entering the Right Transept is a terra-cotta bust of the Archbishop S. Antonino. Above is a fine gothic monument by Tino da Camaino to Tedice Aliotti, Bishop of Fiesole, 1336. A large fresco beyond this tomb ornaments the tomb of Joseph, Patriarch of Constantinople, who died 1440, during the Council of Florence under Eugenius IV. Above it is a canopied monument to Fra Aldobrandini Cavalcanti of Florence, who died in 1229; his figure lies, not on the tomb, but in front of it. At the end of this transept is the Cappella Rucellai, approached by steps, at the top of which is the tomb of Paolo Rucellai, the father of Giovanni, at whose expense the façade of the church was built. Here was the famous so-called Madonna of Cimabue. The Rucellai Madonna was traditionally given to Cimabue, but now to Duccio di Buoninsegna, who worked in the studio of the former. The painting was removed to the Uffizi Gallery in 1948.

Bernardo Rossellino, Tomb of Beata Villana, 1451 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

At the corner of the chapel, on the right, is the monument, by Bernardo Rossellino—with angels drawing back the curtain from her sleeping figure—of the Beata Villana, daughter of Andrea di Messer Lapo, who married one of the Benintendi, and who fled from the world because, when looking at herself in the glass from vanity, she saw a demon dressed in her fine clothes. She died in the odour of Dominican sanctity, 1360, aged twenty-eight. The tomb was erected by her grandson. The other pictures in this chapel are (right), S. Lucia, with the donor, Fra Tommaso Cortese, by Benedetto Ghirlandajo, and (left) the Martyrdom of S. Catherine, by Giuliano Bugiardini (1471-1554).

Immediately after his return from Rome, in 1451, Bernardo Rossellini was entrusted with the tomb of Blessed Villana. If he had given the support of symbolic eagles to the sarcophagus of a great historian, he was able to treat no less happily a subject which had only emerged from the humble virtues; and he placed the heroine who had practiced them, not on a console or in a richly decorated niche, but in a kind of alcove almost at the level of the ground, where one saw two angels, of a ravishing beauty, watching beside of a face transfigured by death and on which the expression of a foretaste of blissful eternity has remained. It was impossible to better understand this truly mystical subject, and to respond better to popular sentiment, which above all called for sympathetic inspirations.

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, 1861 ed., vol. 1, pp. 435–36.

The 1st Chapel (R.), on a line with the high-altar, has on the pillar (right) a rude bas-relief of S. Gregory blessing its founder. A monument commemorates Fra Corrado della Penna, Dominican bishop of Fiesole, 1312.

Benedetto da Maiano, Madonna and Child, 1487-1502 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The next Chapel, of the Strozzi, contains the sarcophagus of Filippo Strozzi the elder (d. 1491), builder of the Strozzi Palace, and an exquisite Tondo of the Madonna and Child, by Benedetto da Majano (1442–1498). The frescoes, much injured by retouching, relate to the lives of S. Philip and S. John the Evangelist, and are by Filippino Lippi (1502). On the right wall S. Philip exorcises a poisonous dragon, which had been worshipped as Mars by the people of Hierapolis in Phrygia: in the lunette above he is crucified by the priests of the dragon. On the left S. John raises to life Drusiana, a woman of Ephesus, who had been full of good works. On the ceiling are the Patriarchs. S. Philip and S. John are represented, with the Virgin and Child, in the beautiful stained glass of the window (c. 1530). In the central light are seen the Virgin and Cintola, and the Presentation: on right, SS. Paul, Lawrence, and Dominic; on left, SS. Peter, John the Baptist, and Peter Martyr.

The High-Altar (where Martin V. created nineteen new cardinals) covers the remains of the Beato Giovanni di Salerno, the Dominican founder of the church. The Choir was originally the chapel of the Ricci, and was decorated at their expense with frescoes by Andrea Orcagna, but these were afterwards painted over (1486) with the stories of the Virgin and S. John Baptist by Domenico Ghirlandajo, who was employed by Giovanni Tornabuoni. On either side of the window are portraits of Tornabuoni and his wife. The window itself is filled with stained glass by Alessandro Florentine, 1491, a pupil of Ghirlandajo. The stalls of the choir were designed by Vasari. Behind the high-altar is an upright bronze effigy of Fra Leonardo di Stazia Dati, grand master of the Dominicans, the work of Lorenzo Ghiberti in 1426.

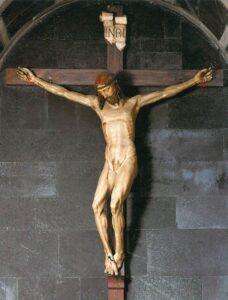

The next Chapel is the Cappella Gondi, which contains a crucifix by Filippo Brunelleschi.

Donato had completed a crucifix in wood, which was placed in the church of Santa Croce, and he desired to have the opinion of Filippo Brunelleschi respecting his work; but he repented of having asked it, since Filippo replied that he had placed a clown upon the cross. And from this time there arose the saying of, “Take wood, then, and make one thyself.” Thereupon Filippo, who never suffered himself to be irritated by anything said to him, however well calculated to provoke him to anger, kept silence for several months, meanwhile preparing a crucifix, also in wood, and of similar size with that of Donato’s, but of such excellence, so well designed, and so carefully executed that when Donato, having been sent forward to his house by Filippo, who intended him a surprise, beheld the work (the undertaking of which by Filippo was entirely unknown to him), he was utterly confounded; and, having in his hand an apron full of eggs and other things on which his friend and himself were to dine together, he suffered the whole to fall to the ground, while he regarded the work before him in the very extremity of amazement. The artistic and ingenious manner in which Filippo had disposed and united the legs, trunk, and arms of the figure was alike obvious and surprising to Donato, who not only confessed himself conquered, but declared the work a miracle.

For a somewhat different translation see Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol.1, pp. 308–09.

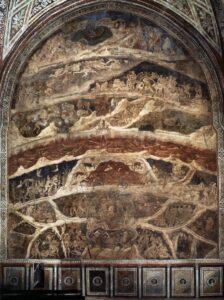

Next follows the beautiful Cappella de’ Gaddi, by Dosio, 1533, with the raising of Jairus’ daughter, by Bronzino, and two reliefs, by Giovanni dell’ Opera, over tombs of the Gaddi. The chapel at the end of the left transept is a second Cappella Strozzi, and contains the relics of the Beato Alessio degli Strozzi. The walls have frescoes of the Last Judgment and Hell, by Nardo di Cione10Hare credits Andrea di Cione, Nardo’s brother who is better known as Orcagna, and Leonardo Orcagna (1357).

Nardo di Cione, Last Judgment, 1354–57 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Nardo di Cione, Hell, 1354–57 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

This is quite another thing than the hell of Campo Santo in Pisa; here is found the whole topography of Dantesque hell, at least as much as the surface which the painter could dispose of allowed him. Thus there was no place in the field of the fresco for the hypocrites, but the name is written at the end of the table, and shows the intention of the painter to have them enter it if the space hadn’t missed him. Moreover, nothing is disguised or concealed of what is most believed and sometimes coarser in the painter of certain tortures; the brawl of master Adam, the dropsy and thirsty counterfeiter, is represented naturally; it looks like a duel of boxers. Flatterers are plunged into the kind of mire by which Dante wanted to express all his distaste for souls infected with this vice which stinks of courts.

What is stranger, there, in a chapel, the painter’s brush did not hesitate to reproduce this bizarre alliance of Christian dogma and pagan fables that the poet had allowed himself, docile to the genius of his time, and which amazes even more when you see it than when you read it. Thus the centaurs pursuing, on the walls of Santa Maria Novella, as in the Divine Comedy, violent and piercing them with arrows; the harpies, profane memories of the Aeneid, where they seem more in their place than in the Catholic epic, are perched on the sad branches from which they throw mournful complaints; finally the furies rise above the abyss on the ablaze tower.

In front of hell, Orcagna represented the glory of paradise. Dante’s celestial circles did not lend themselves to painting like the infernal region. However, what dominates these kinds of paintings in the Middle Ages, namely, the glorification of the Virgin, is also what crowns Dante’s great epic.

Jean-Jacques Ampère, Études Littéraires d’après Nature, pp. 237–38.

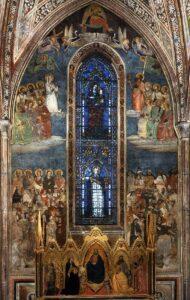

Orcagna, Strozzi Altarpiece, 1354–57 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The restored altar-piece, by Andrea Orcagna, shews S. Dominic presented to the Virgin. Beneath the steps leading to this chapel is an Entombment by Giottino, and, above, the portrait of a Bishop of Fiesole, 1348, who is buried here.

The Sacristy, now the museum shop, by Fra Jacopo Talenti, 1350, has a beautiful lavatory by Giovanni della Robbia. One of the twelve banners is preserved here which S. Peter Martyr presented to his twelve captains when he sent them forth, on Ascension Day, 1244, to extirpate the Paterini. At the angle of the transept is a vase, from Impruneta, resting on a very poor marble figure by Michelangelo.

Entering the Left Aisle, beneath the first altar are the bones of Beata Villana. Above is a picture of the Dominican missionary, S. Hyacinth, by Bronzino. Near the end of this aisle is a black marble monument to Antonio Strozzi by Andrea da Fiesole. The pulpit was made by Maestro Lazaro, from designs of Brunelleschi.

The first cloister one descends to is called Il Sepolcreto, and has charms of many kinds besides faded grotesque frescoes and mediaeval tombs.

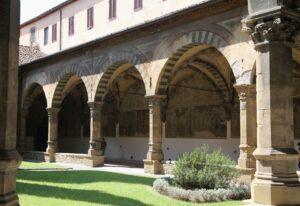

Chiostro Verde (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Chiostro Verde is supported by handsome pillars, but much spoilt by paint. The lunette over the entrance door is by Stefano del Ponte Vecchio. It is surrounded by frescoes painted in various shades of green. On the right of the entrance from the church are some Dominican saints by Spinello Aretino. The left wall, as far as the Sacrifice of Noah, is by Paolo Uccello, the remaining twenty-four pictures by his friend Dello Delli, 1401. They are painted in terra verde, whence the name of the cloister.

The sweet faded groups—a slim Rebecca listening to Eliezer’s tale, and looking maiden pleasure at his gifts; a shivering Adam and Eve chased out of Paradise; an Adam and Eve dismally digging and stitching respectively; Old Testament stories that time has blurred, that weather—even in this dry air—has rubbed out and bedimmed, and that yet, in many cases, still tell their curious paint tale decipherably.

Rhoda Broughton, Alas, vol. 2, p. 289.

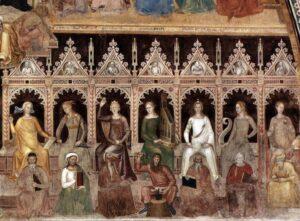

Andrea da Firenze, Triumph of the Church, c. 1366–68 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

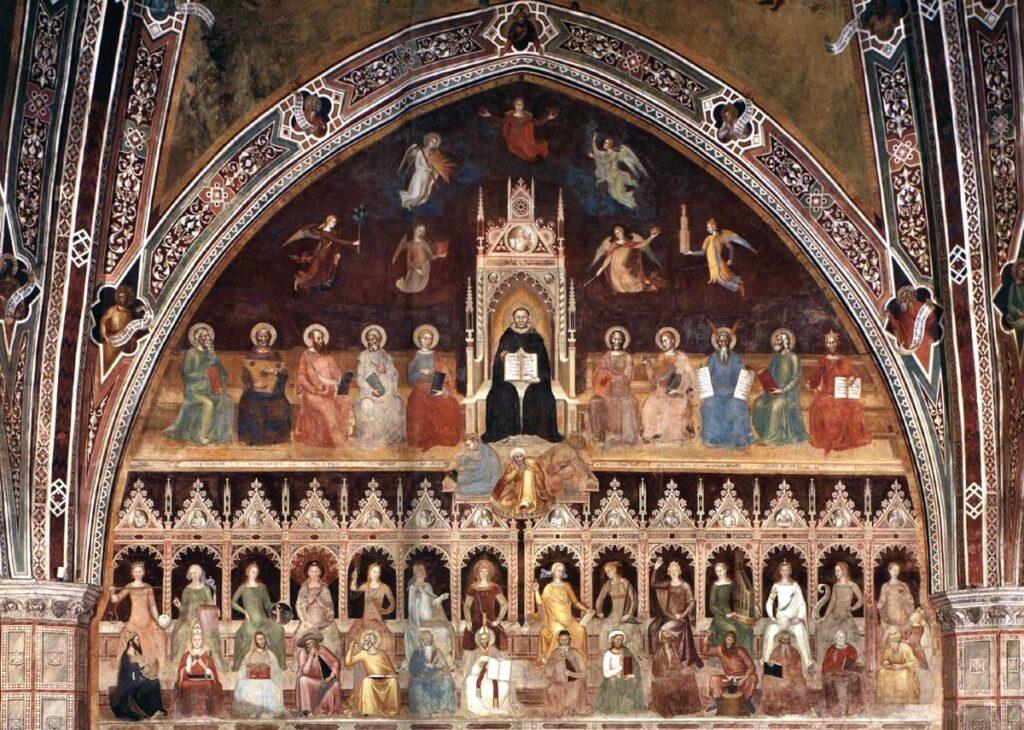

On the right, two windows with beautiful tracery are those of the Cappella degli Spagnuoli, used for the attendants of Eleanora of Toledo, wife of Cosimo I. It was built for Buonamico Guidalotti in 1326, by Fra Jacopo de’ Talenti da Nipozzano, dedicated to the Holy Sacrament, and used as a chapter-house. It is covered within with frescoes in glorification of the mediaeval Dominicans, attributed to Taddeo Gaddi and Simone Memmi. On the north wall are the Crucifixion, the Bearing of the Cross, and the Descent into Limbo. On the left (W.) is the Apotheosis of S. Thomas Aquinas, at whose feet are seen crushed Arius, Sabellius, and Averroes; on the right (E.), the Church Militant and Triumphant, defended by the Dominicans (Domino canes).

On the four spandrels of the ribbed vault are depicted: (1) The Resurrection; (2) Ascension; (3) The Descent of the Holy Spirit; (4) Christ saving the ship (i.e. the Church) during the tempest. On the wall of entrance are scenes from the lives of SS. Dominic and Peter Martyr, much damaged and much restored. The apse contains six niches in its side-walls decorated with figures of SS. Lorenzo, Domenico, Vincenzo Ferrerio, Ermengilda, Vincenzo Martire, and Isidore. The crucifix is by Pieratti.

The subjects (said to have been selected by Fra Jacopo Passavanti) are chosen with a depth of thought, a propriety and taste, to which those of the Camera della Segnatura, painted by Raffaelle in the Vatican, afford the only parallel example. Each composition is perfect in itself, yet each derives significance from juxtaposition with its neighbour, and one idea pervades the whole, the Unity of the Body of Christ, the Church, and the glory of the Order of S. Dominic as the defenders and preservers of that Unity. This chapel, therefore, is to the Dominicans what the church of Assisi is to the Franciscans, the graphic mirror of their spirit, the apotheosis of their fame.

Lord Lindsay, Christian Art, vol. 2, p. 146.

The admirable frescoes of this chapel, whose authors are Taddeo Gaddi and Simone Memmi, show to the eye this mixture of history and allegory, this character both encyclopedic and symbolic, which belongs to the work of Dante, as well as many other poems of the Middle Ages, conceived in the same spirit, but not with the same genius. Simone Memmi painted a picture of civil and ecclesiastical society: all the social conditions are brought together in this painting, which is like an immense review of humanity. The pope and the emperor appear in the center, according to Dante’s system; portraits of purely allegorical characters, or whose image is taken for an allegory without ceasing to be a portrait. Laura represents the will in Memmi’s painting, like Beatrice, contemplation in Dante’s work.

We can notice that Dante is in the habit of choosing a character in history as the type of a quality, a vice, a science, and in turn uses this process and allegory to achieve an abstraction. Likewise, in Taddeo Gaddi’s fresco, fourteen sciences or arts are expressed by figures of women, below which are placed typical characters who are historical symbols of each science. The first is civil law with Justinian; canon law only comes after. This order is well in the political ideas of Dante. The great part he wanted to do in this world with imperial powers led him to also choose Justinian to represent Justice in Mercury, planet where he placed the reward of this virtue, despite what morals and l’ orthodoxy could blame Theodora’s husband.

In these paintings one thus constantly finds conceptions similar to those of Dante, or inspired by them; we go back to it as to a spring; or one descends towards it as to a sea which received in its bosom all the currents of ideas which nourished art in the Middle Ages.

Jean-Jacques Ampère, La Grèce, Rome & Dante: Études Littéraires d’après Nature, pp. 238–39.

In the Allegorical fresco on the left wall the scheme is carried out with prosaic precision. It consists of two sections:—

(1) S. Thomas Aquinas enthroned as the great teacher, displaying the volume of Summa Theologiæ. Above and around are represented floating in the air seraphs and archangels. At each side of him sit the Prophetic and Apostolic teachers:—(R.) SS. Matthew, Luke, Moses, Isaiah, Solomon; (L.) SS. John, Mark, Paul, David, Job. Below the feet of S. Thomas are Arius, Sabellius, and Averroes.

(2) Divides into fourteen female figures of Virtues and Sciences, with their corresponding male representatives sitting below them (L. to R.): —

(1) Civil Law: Justinian

(2) Canon Law: Clement V.

(3) Practical Theology: Peter Lombard

(4) Speculative Theology: Boethius

(5) Faith: Dionysius Areopagiticus

(6) Hope: S. John Damascenus

(7) Charity: S. Augustine

(8) Arithmetic: Pythag

(9) Geometry: Euclid

(10) Astronomy: Ptolemy

(11) Music: Tubal-Cain

(12) Dialectic: Aristotle

(13) Rhetoric: Cicero

(14) Grammar: Priscian

Taddeo Gaddi here represents philosophy, fourteen women, the seven profane sciences and the seven sacred sciences, all ranged in a straight line, each seated on a richly ornamented gothic chair, and each with the great man at her feet who acts as her interpreter; above them, in a still more delicate and elaborate chair, is St. Thomas the king of all sciences, trampling under foot the three great heretics Arius, Sabellius and Averröes, whilst on either side sit the prophets of the old and the apostles of the new Law gravely presiding with their insignia, and to whom, in the circular space around their heads, are angels, symmetrically posed, bringing books, flowers and flames. Subject, composition, architecture and characters, the entire fresco resembles the sculptured portal of a cathedral.—Quite like this and still more symbolical, is the fresco by Simone Memmi, which, opposite to it, represents the Church. The object here is to figure the entire Christian establishment, and allegory is pushed even to the ludicrous. On the flank of Santa Maria di Fiore, which is the Church, the Pope, surrounded by cardinals and dignitaries, regards a community of believers at his feet in the shape of a flock of lambs reposing under the protection of a faithful Dominican police. Some, the dogs of the Lord (Domini canes) are strangling heretical wolves. Others, preachers, are exhorting and making converts. The procession turns, and the eye following it upward, beholds the vain joys of the world, frivolous dances, and, after this, repentance and penitence; farther on the celestial gates guarded by St. Peter into which pass redeemed souls that have become young and innocent like babes; after these the thronging choir of the Blessed who continue on into heaven in the shape of angels, while the Virgin and the Lamb are surrounded by four symbolic animals, with the Father on the summit of the beam rallying and drawing to him the triumphant militant crowd ranged in successive stories from earth to Paradise.—The two pictures face each other and form a sort of abridgment of Dominican theology. But this is all, and theology is not painting any more than an emblem is a bodily entity.

Hippolyte Taine, Florence and Venice, pp. 106–107.

The attribution of especial figures to monarchs, poets, painters, &c., is not supported satisfactorily; but it amuses, and has some justification.

In this chapel the popular Council of Eight held their meetings after the Rising of the Ciompi (1378). Beyond the chapel is a fresco of the Madonna and Saints by Simone Memmi.

The Great Cloister is surrounded by frescoes relating to the history of the Dominicans, and introducing many of the old buildings of Florence in their backgrounds. The 13th lunette, by Gamberucci, represents the foundation of S. Maria Novella by Fra Giovanni da Salerno. In a passage leading from the small cloister, in the tomb of the Marchesa Strozzi Ridolfi, are two frescoes attributed to Giotto—the Meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate, and the Birth of the Virgin.

If you can be pleased with this, you can see Florence. But if not, — by all means amuse yourself there, if you find it amusing, as long as you like; you can never see it.

John Ruskin, Mornings in Florence, vol. 1, p. 30.

In the first fresco we ought to see how—

S. Anna has moved quickest; her dress just falls into folds sloping backwards enough to tell you so much. She has caught S. Joachim by his mantle, and draws him to her softly by that. S. Joachim lays his hand under her arm, seeing she is like to faint, and holds her up. They do not kiss each other—only look into each other’s eyes, and God’s angel lays his hand on their heads.

John Ruskin, Mornings in Florence, vol.1, p. 31.

Among the frescoes is one displaying the contest in Piazza della Croce al Trebbio, between Pietro Martire, his followers, and the heretics. The twentieth fresco, by Santi di Tito, represents S. Dominic and his brethren being waited upon by angels. Another shows the Signoria receiving Sant’ Antonino at the Palazzo Vecchio.

The Ciompi in 1378 made this cloister their head centre, and held their meetings in a chapel dedicated to San Niccolo, which had been built by Bishop Agnolo Acciajuoli in 1303.

Pope Boniface VIII appointing Charles de Valois to a delegation to the Guelf factions (photo via internetculturale)

The church is intimately associated with the memorable visit of Charles de Valois, the pretended peacemaker who had entered the city with 2000 troops, “armed with the lance,” says Dante, “that Judas tilted with” (Purgatorio 20:71–2). Here in the presence of the Priors, Podestà, and Bishop and chief citizens of all denominations, he promised on the faith of a king’s son to preserve peace and keep the city in prosperity; and then caused Corso Donati to burst into the town, break open the prisons, and drive the Priors from their chapter-house; and set murder flaming about the city for five days, during which the royal traitor ensnared the chiefs of the Bianchi and meanwhile forged letters to prove their treachery.

Before his departure no less than 600 prominent citizens were driven into exile, and their property was confiscated. They found asylums in Pisa, Pistoia, Arezzo, and Bologna. On January 27, 1302, Dante was condemned to pay a heavy fine on a fabricated charge of peculation while a prior; but there is now no doubt that he was punished for refusing his official sanction to the payment of subsidies to Charles de Valois.

F. A. Hyett, History of Florence, p. 72.

Charles, in fact, placed the Neri in power. All this resulted from the assembly at S. Maria Novella.

Pope Martin V. (Colonna), after his acknowledgment by the Council of Constance, resided at. S. Maria Novella from February 1419 to September 1420, as the guest of the Commonwealth, in magnificent lodgings which were prepared for him adjoining the cloisters. The church was the scene of the Council of Florence, 1439, at which Pope Eugenius IV. (who had also taken refuge in the convent) presided wearing a mitre made for him by Lorenzo Ghiberti, encrusted with precious stones, valued at 30,000 florins.

Part of the old convent is now given to the Società dell’ Accattonaggio, which relieves mendicancy by finding work for beggars.

On the north of S. Maria Novella is the Piazza Vecchia di S. Maria Novella, now Piazza dell’ Unità Italiana, which was a great meeting-place of the Guelphs and Ghibellines. No. 7, once occupied by railway offices, was the Palazzo Cerretani, and contains a great hall with decorations of 1650, and a gallery with a ceiling by Vincenzo Meucci, 1743, representing the meeting of Frederick Barbarossa and Alexander III.11Arms: azure, on a bend or, three trees vert.

Gruppo Toscano, Santa Maria Novella Rail Station, 1932–34 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Gruppo Toscano, Santa Maria Novella Rail Station, 1932–34 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Piazza dell’ Unità Italiana abuts the Piazza della Stazione that fronts Stazione Centrale di Santa Maria Novella, the main rail station. Built 1932–34 by the Gruppo Tuscano, which included Italo Gamberini, Giovanni Michelucci, and others, it is generally considered the most significant modern structure in the city. The vast interior concourse, approximately 358 x 72 feet, if floored in white marble articulated with red marble strips. The concrete roof is fully glazed to the north.

From the Piazza della Stazione, the Via Nazionale leads (right) to the ugly square called Piazza dell’ Indipendenza. The street contains a beautiful tabernacle by Giovanni della Robbia, ordered in 1522 by the “Potenza del Regno di Betlemme,” and crosses the Via Faenza, close to the little gothic church of S. Jacopo in Campo Corbolini, founded 1206, which belonged to the Knights of S. John of Jerusalem. On the right of the entrance is the tomb of the prior Pietro da Imola, 1320, and, opposite, that of the prior De Rossi, 1398. Above the first altar on the right is an ill-restored Marriage of S. Catherine, by Ridolfo Ghirlandajo. On the left occurs the epitaph of the prior Benini, 1453, and, on the right, the beautiful tomb of the prior Luigi Tornabuoni of Pisa, which he erected for himself in 1515. It is by a sculptor of Fiesole, only known as “Il Cicilia.” A few steps on the other side the Via Nazionale is the secularised Convent of S. Onofrio, now called Cenacolo di Foligno, which contains the beautiful Cenacolo, long attributed to Raffaelle. This fresco was more recently attributed to Neri de’ Bicci, sometimes to Gerino da Pistoia,12See A. H. Layard, The Italian schools of painting, vol. 1, pp. 246–47. and finally by Morelli to Giannicola Manni. Currently most scholars attribute the work to Perugino.

Pietro Perugino, The Last Supper, 1493-96 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Christ is in the centre; His right hand is raised, and He is about to speak; the left hand is laid, with extreme tenderness in the attitude and expression, on the shoulder of John, who reclines upon Him. To the right of Christ is S. Peter, the head of the usual character; next to him S. Andrew, with flowing grey hair and long divided beard; S. James minor, the head declined and resembling Christ; he holds a cup. S. Philip is seen in profile with a white beard. S. James major, at the extreme end of the table, looks out of the picture: Raffaelle has apparently represented himself in this apostle. On the left of Christ, after S. John, is S. Bartholomew; he holds a knife, and has the black beard and dark complexion usually given to him. Then Matthew, something like Peter, but milder and more refined. Thomas, young and handsome, pours wine into a cup; last, on the right, are Simon and Jude: Raffaelle has followed the tradition which supposes them young and kinsmen of our Saviour. Judas sits on a stool on the near side of the table, opposite to Christ, and while he dips his hand into the dish, he looks round to the spectators; he has the Jewish features, red hair and beard, and a bad expression. All have glories; but the glory round the head of Judas is much smaller than the others.

Anna Jameson, Sacred Art, vol. 1, p. 271.

Hither has been transported from the Uffizi the collection called the Galleria Ferroni, bequeathed to the State by the last representative of the Ferroni family.13Arms of Ferroni: Azure, a mailed arm holding a sword, arg. and in chief, a fleur-de-lis or. The best pictures are—

Teniers. A Kitchen Interior.

Lorenzo di Credi. The Virgin and S. John praying over the Child Jesus.

Carlo Dolci. The Annunciation, in two pictures—the Angel very beautiful, the Madonna naïve.

Schidone. Holy Family.

An oratory adjoining No. 72 Via Faenza, formerly the church of S. Giuliano, has an admirable lunette, by Andrea del Castagno, of the Crucifixion with the Virgin and S. John and S. Julian. At No. 66 in the Via Cennini (the next street on the left) is a tabernacle by Giovanni di S. Giovanni. The Via Faenza skirts the gardens (left) of the Villino Strozzi, built by Baccio d’ Agnolo, and altered by Silvani in 1638. The ceilings of the ground floors are by Poccetti. The street ends at the Fortezza da Basso, built by Clement VII. for Alessandro de’ Medici on the site of a convent and a hospice which was the residence of Sir John Hawkwood. Here Filippo Strozzi, who had lent the money to build the fortress, was imprisoned after being taken prisoner at Montemurlo, and was found dead in his dungeon. Giovanni Bandini, a former favourite of Cosimo I., was also imprisoned here and starved to death by his master.

Turning to the left from the Piazza S. Maria Novella, down the Via della Scala, a door on the right, with a frame-work of fruit and flowers, marks the entrance (No. 14) to the Spezeria of S. Maria Novella, where excellent liqueurs (Alkermes) and scented and medicinal waters were made by the monks, and where they are still made from the old recipes and sold. The pretty, cool, frescoed halls, filled with sweet scents, are well worth visiting, and there is a chapel with lovely frescoes by Spinello Aretino, of the Washing of the Feet, the Last Supper, Our Saviour bearing His Cross, the Scourging, the Mocking, the Crucifixion, and the Deposition from the Cross. The bright tones of varied red, and the golden aureoles of the Apostles, together with the painted vaulting with blue ground, in the Giottesque manner, and a chequered floor, make this a most radiant and fascinating chamber, recalling the larger Sala del Cambio at Perugia. In the adjoining Spezeria are glorious great jars full of soft drugs and sweet unguents, glass retorts wet with delicious dews of subtle exhalation in them, made from Dulcamara, Viole Mammole, Malva Peonia, Giuggole and Canna Montana; such scents as might have come from the garden in Angelico’s picture of Paradise, where the Beatified wave and dance in a floral tide. We seem to see endless summers pass before us, with Elysian meadows, streamlets, and solemn woodlands, in which careful Frati are bending to cull the valued flowers and herbs, and now and then holding them up in the celestial air in order to be sure of them. The great hall, where Eugenius IV. held his court when in Florence, was in the part of the convent now occupied by the Spezeria.

The Via della Scala takes its name from the Foundling Hospital of S. Maria della Scala, founded by one Cione di Lapo de’ Pollini. The children are brought up entirely by goats; when the children cry, the goats come and give them suck. On the outside of the chapel is an inscription, saying that 20,000 persons were buried there during the plague of 1479. No. 6 is the Palazzo del Borgo, adorned with graffiti. No. 32 was the house of the Beato Ippolito Galantini, 1565–1619. On the right (No. 56) the suppressed Convent of S. Jacopo in Ripoli has an exquisite specimen of Luca della Robbia in the lunette over the church door. Alessandra della Scala, the original of “Romola,” lived in the Via della Scala, and not in the Via dei Bardi.

Turning to the left, down the Via degli Oricellari, on the right were the high iron gates of the Rucellai Gardens, which belonged to Bianca Cappello, where the Platonic Academy met which was founded by Cosimo de’ Medici—Pater Patriae. The names of the Academicians were inscribed on a column in the garden; a statue of Polyphemus was by Antonio Novelli. Here Niccolò Macchiavelli recited his discourses on Livy, and Giovanni Rucellai read Rosmunda, one of the earliest Italian tragedies, to Leo X. Bianca Cappello lived in the palace (which was designed by Leon Battista Alberti) before her marriage with Francesco I. Part of these gardens, probably the most historic in the world, were condemned to destruction by the contemptible folly of the municipality in 1891, that streets with the done-to-death names of Garibaldi, Magenta, &c., might occupy the site.

At the end of the parallel street, called Porto Prato, is the Church of S. Lucia sul Prato, which contains a Nativity by Dom. Ghirlandajo behind the high-altar.

Beyond this are the Cascine, the charming characteristic park of Florence, delightful meadows alternating with groves of trees, chiefly ilex and pine, and intersected and encircled by pleasant carriage-drives and walks. The much maligned monument to Vittorio Emanuele II, formerly in Piazza della Repubblica, was moved to the Cascine in 1932.

The sunny drive along the Arno is the most popular in winter, and lovely are the views, both towards Bellosguardo and looking back upon the town. In summer, people are glad to take refuge in the shadier avenues on the side towards the mountains. Carriages assemble, flowers are handed about, and all the gossip of the day is discussed on the piazza—Piazzale del Re—facing the Arno, near what was the favourite dairy-farm of the Grand-Dukes. Here Shelley wrote that most Æolian of English lyrics, his Ode to the West Wind.

Of their own accord, the coachmen take, and without being told, the road to Piazzone; there they stop without even having to make a sign to them.

This is because the Piazzone in Florence offers what perhaps no other city offers: a sort of open-air circle, where everyone receives and returns their visits; it goes without saying that the visitors are the men. The women stay in the carriages, the men go from one to the other, chatting at the door, these on foot, those on horseback, some more familiar mounted on the step.

This is where life is settled, where glances are exchanged, where dates are arranged.

In the midst of all these carriages, the florists pass, throwing bouquets of roses and violets, which they will go to the cafe the next morning, to ask the men for the price by presenting them with a carnation.

Alexandre Dumas, Une année à Florence, p. 174.

You remember down at Florence our Cascine,

Where the people on the feast-days walk and drive,

And through the trees, long drawn in many a green way,

O’er-roofing hum and murmur like a hive,

The river and the mountains look alive?

You remember the piazzone there, the stand-place

Of carriages alive with Florence beauties,

Who lean and melt to music as the band plays,

To smile and chat with some one who afoot is,

Or on horseback, in observance of male duties?

‘Tis so pretty, in the afternoons of summer,

So many gracious faces brought together!

Call it rout, or call it concert, they have come here,

In the floating of the fan and of the feather,

To reciprocate with beauty the fine weather.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, The Dance, 1–3.

Giotto di Bondone, Crucifix, 1300-15 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

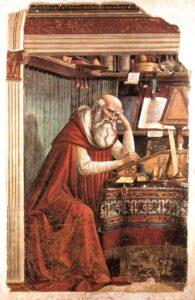

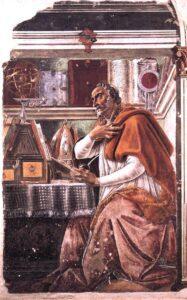

Returning (E.) along the Borg’ Ognisanti—which runs along so as to strike the Arno at Ponte alla Carraia—we pass the Church of Ogni Santi, also called San Salvador, with a beautiful coronation-group by Giovanni della Robbia over its door. On either side of the nave (near the middle) are frescoes: that on the left—by Dom. Ghirlandajo, 1480—represents S. Jerome; that on the right, over a confessional, by Sandro Botticelli—is S. Augustine. The cupola is painted by Giov. di S. Giovanni. In the left transept is a crucifix by Giotto (?); in the sacristy a Crucifixion by Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, a pupil of Taddeo Gaddi. Botticelli was buried here in 1510.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Madonna of Mercy, c. 1472 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

In February 1898, the monk Roberto Rolozzi informed the Inspector of Fine Arts that he had found, from an old book in the convent, that beneath two of the pictures in the church important frescoes were concealed. The frescoes were discovered. One was an unimportant XVI. c. representation of the Trinity, but beneath a picture of S. Elizabeth of Portugal, by Rosselli, was discovered an exquisite fresco by Ghirlandajo, which is spoken of by Vasari. In the lunette is Our Lady of Mercy, sheltering members of the Vespucci family—for whom the picture was ordered—under her mantle. The youth on the right is believed to be the famous navigator, Amerigo Vespucci.

The first pictures painted by Domenico were for the chapel of the Vespucci, in the church of Ognissanti, where there is a Dead Christ with numerous Saints. Over an arch in the same chapel there is a Misericordia, wherein Domenico has portrayed the likeness of Amerigo Vespucci, who sailed to the Indies; and in the refectory of the convent (of Ognissanti) he painted a fresco of the Last Supper.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 2, p. 169.

Beneath—over the altar of the Pietà—is a Descent from the Cross, of marvellous beauty, in which the figures are believed to be portraits of persons living in the time of the artist.

From the left transept we enter the Cloisters, of which there are two, one occupied for soldiers, which have interesting frescoes relating to the life of S. Francis by Giov. di S. Giovanni and Jacopo Ligozzi, hard in tone and drawing, but interesting. In the Refectory is a ciborium by Agostino di Duccio, and a grand fresco of the Last Supper by Dom. Ghirlandajo, executed in 1480.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Last Supper, 1480 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Last Supper is composed in the traditional form, with the Saviour in the centre of a double-winged table, and the traitor alone at the opposite side between him and the spectator. Yet the old symmetry of sitting apostles is already varied by an exhibition of the moving thought in the assemblage, and whilst Peter meaningly points at Judas, a group on the left presses forward, eager to fathom the words of the Redeemer, in a manner which recalls the masterpiece of Leonardo. A great variety of individual expression and action is also apparent, and the melancholy in the face of the apostle next S. John Evangelist is remarkable.

Crowe and Cavalcaselle, New History of Painting in Italy, vol. 2, pp. 463–64.

Nearly opposite, in the Borg’ Ognisanti, is the Hospital of the Benfratelli, which was founded in 1400 by Simone Vespucci, and given in 1587 to the monks of S. Giovanni di Dio, who came hither from Granada, whence the pomegranate and cross on the arms of the hospital. Of the family of the founders, which gave three gonfalonieri and twenty-five priori to the State, was Amerigo Vespucci (1451–1516), the most illustrious of the followers of Columbus, who gave his name to America. No. 4 Borg’ Ognisanti is the Palazzo Fossombroni, where Count Vittorio Fossombroni, the illustrious minister of Ferdinand III., died in 1844.

In the Piazza Ognissanti (formerly Piazza Manin), at the house which is now the Hôtel de la Ville, was the residence of Caroline Murat. The ancient Palazzo Quaratesi, built from designs of Brunelleschi, and formerly inhabited by the Gondi, contains the collection known as the Galleria Pisani. The bronze statue of Daniele Manin, by Urbano Nano (1889), formerly in the piazza was moved to piazzale Galileo in 1931 and replaced in 1937 with Hercules Strangling the Nemean Lion by Romano Romanelli. Close to this is the entrance of the Ponte alla Carraja, built as it now stands, in 1559, by Ammanati, for Cosimo I. The Ponte alla Carraia was destroyed in 1944 and subsequently rebuilt in 1948 by Ettore Fagiuoli with five arches like the original.

The Via de’ Fossi, which opens on the left, is named from the moat surrounding the walls of the second circle. The little Piazza degli Ottaviani at its entrance is named from an extinct family. No. 16 is the Palazzo Nicolini, which formerly belonged to the Marchesi del Monte di S. Maria.

On the left of the Via de’ Fossi opens the Via Palazzuolo, running west again toward the Cascine. On its left is the Piazza S. Paolino, named from an interesting little church, of which Poliziano was the priest. The façade bears the arms of Leo X., Giulio de’ Medici, and a Bishop Pandolfini. The monuments of the Albizzi, which it contains, were brought from S. Pietro Maggiore. Farther on the left [No. 17], past Via di Porcellana, is the church of S. Francesco, which was built by Ippolito Galantini, and belonged to the confraternity of the Vanchetoni, founded by Cardinal Alessandro de’ Medici in 1602. They were bound not to speak during their processions, whence the name, from Vanno chetoni (They go in silence). Within may be seen two marble busts of the Child-Christ and S. John, by Rossellino. On the Wednesday before Sexagesima the brethren still give a supper to a hundred poor persons of the parish. The ceiling of the church has pictures by Giovanni di S. Giovanni. The Infant Jesus and S. John, at the high-altar, are probably by Donatello.

On the right of the Via de’ Fossi opens the Via della Spada, containing (right) the Museo Marino Marini in the former church of S. Pancrazio. The ancient church with sphinxes on either side of the entrance has been frequently rebuilt (1488). Opened in 1988 after extensive remodeling of the interior by Bruno Sacchi and Lorenzo Papi, the museum is the first in Florence to represent modern and contemporary art. The permanent collection contains 183 works by Marini (1901–1980). Franciabigio was buried here. In the cloister of the adjoining convent, which belonged to Vallombrosa, is a famous fresco of S. Giovanni Gualberto, surrounded by bishops and saints, the masterpiece of Neri de’ Bicci, but attributed partly to Masaccio.

Here is the Cappella Rucellai, built by Leon Battista Alberti for Bernardo Rucellai, c. 1467, and a good specimen of Florentine renaissance architecture. The chapel contains Alberti’s Sacellum (shrine) of the Holy Sepulchre.

From the Ponte alla Carraia the Lung’ Arno Corsini brings us direct to the Ponte SS. Trinità, founded in 1353 by Lamberto Frescobaldi, but several times rebuilt, the penultimate time by Ammanati. The Ponte Trinità was destroyed by the retreating German Army in August 1944. The bridge was rebuilt in 1952 from the original plans and using much salvaged stone. Its proportions are exceedingly beautiful, with its sharp and well-stained buttresses and grass-lined mouldings. Four statues of the Seasons decorate its parapets, having been erected in 1608 in honour of the marriage of Cosimo II. and Magdalen of Austria. The little brick bell tower of S. Jacopo, and the corbelled-out, river-side houses beyond, are well seen from here.

The river rushes through the midst of the palaces like a crystal arrow, and it is hard to tell, when you see all by the clear sunset, whether those churches, and houses, and windows, and bridges, and people walking, in the water or out of the water, are the real walls, and windows, and bridges, and people, and churches. The only difference is that, down below, there is a double movement; the movement of the stream besides the movement of life. For the rest, the distinctness of the eye is as great in one as in the other.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Letters, vol. 1, ed. 1897, p. 332.

I can but muse in hope upon this shore

Of golden Arno as it shoots away

Through Florence’ heart beneath her bridges four:

Bent bridges, seeming to strain off like bows,

And tremble while the arrowy undertide

Shoots on and cleaves the marble as it goes,

And strikes up palace-walls on either side,

And froths the cornice out in glittering rows,

With doors and windows quaintly multiplied,

And terrace-sweeps, and gazers upon all,

By whom if flowers and kerchief were thrown out

From any lattice there, the same would fall

Into the river underneath, no doubt,

It runs so close and fast ‘twixt wall and wall.

How beautiful! the mountains from without

In silence listen for the word said next.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Casa Guidi Windows, Part 1:3.

The Palazzo Frescobaldi,14Arms of Frescobaldi: Gules, 3 castles argent, and a chief or. on the opposite side of the bridge, recalls the memory of Dianora Salviati, wife of Bartolomeo Frescobaldi, who was the mother of fifty-two children, having never produced less than three at a birth.

Dianora Salviati, wife of Bartolomeo Frescobaldi, had fifty-two children, and never fewer than three in childbirth, as reported by Giov. Schenchio in the books of his observations, new, admirable and monstrous, that is, in the Fourth Book of Childbirth, on page 144.

Few families of the XIII. c. were more illustrious than the Frescobaldi, of whom were Dino, the friend of Dante, to whom the world owes the first seven cantos of the Inferno, which he saved and carried secretly to Malaspina, when the poet’s house was burnt. He was also himself known as a poet, as was his son Matteo in the XIV. c.

In the Via Parione (No. 7), behind the Lung’ Arno Corsini, is the entrance of the Palazzo Corsini, which contains a collection of pictures.

The wide staircase, adorned with a statue of Pope Clement XII. (Lorenzo Corsini, 1730–40), is exceedingly handsome, and leads to a great hall, which opens into a stately suite of rooms filled with pictures. Among them are: —

1st Room:

- Sustermanns. Portrait of Ferdinando de’ Medici, son of Cosimo III.

- Pontormo. Male portrait.

- Sustermanns. Vittoria della Rovere, wife of Ferdinando de Medici.

- Sustermanns. Cristina of Lorraine, wife of Ferdinand II.

- Sustermanns. Ferdinand II.

2nd Room:

- Teniers. Old man warming himself.

3rd Room:

- Cigoli. Head of the dead Christ—very beautiful.

19, 21. Cristiano Scibold. Portraits of the painter and his wife, extraordinarily powerful and. human.

- Paris Bordone. Man in Venetian costume.

- Sustermanns. Portrait of Cardinal Neri Corsini.

- Giulio Romano. Copy of the Violin-Player of Raffaelle.

- Crist. Allori. S. Andrea Corsini.

- Rid. Ghirlandajo. Male portrait.

4th Room:

-

Sandro Botticelli, Virgin and Child with Angels, c. 1500 (photo via Auckland Art Gallery)

Luca Signorelli, Virgin and Child with Sts Jerome and Bernard of Clairvaux, 1492-93 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Domenichino. Portrait of Cardinal Filomarino.

- Raffaelle (?). Sketch of Julius II., with the holes pricked for transferring it to canvas.

- Luca Signorelli. Virgin and Child, with S. Jerome and S. Bernard.

- Fra Bartolommeo, 1511. Holy Family.

- Filippino Lippi. Virgin and Child with angels.

- Botticelli. Virgin and Child with angels.

- Filippino Lippi. Virgin and Child.

- Carlo Dolce. Poetry, said to be his masterpiece.

- Raffaellino di Carlo. Virgin and Child and S. John.

5th (Yellow) Room, amongst many family portraits:

Neri Corsini, Captain of the Guard under Cosimo III., and afterwards Cardinal, who built the Corsini Palace at Rome.

6th Room:

- Ang. Bronzino, 1540. Portrait of Baccio Valori.

- Holbein. Male portrait.

- Botticelli. A Goldsmith.

- Sebastiano del Piombo. The Bearing of the Cross.

Several rooms have recently been decorated with the magnificent hangings of Clement XII., brought—with his throne—from the Palazzo Corsini at Rome, together with much ancient furniture. The MSS. include the Corsini banking-books of the time of our Queen Elizabeth.

The family of Corsini had their origin in the Conti di Gangalandi, whose history is lost in the darkness of ages. The first document bearing the name of Corsini is of 1230. In the same century Neri di Corsini became prior and gonfaloniere, and since then the bishops, cardinals, pope, marquises, and princes of the family have ever borne a part—generally a noble part—in Italian history. Andrea, Bishop of Fiesole, d. 1379, was canonised by Urban VIII., and his brother Neri was beatified. Amerigo Corsini in 1420 became the first Archbishop of Florence.

No. 4 and No. 2, near the Corsini Palace, belonged to the powerful Guelph family of the Gianfigliazzi, and No. 4 still bears their arms. [Or, a lion azure, clawed and langued gules.] An inscription on No. 2 (Palazzo Masetti) says that the tragic dramatist and poet Vittorio Alfieri (1749–1803) lived and died there. Canova designed his tomb in Santa Croce.