7.1: Oltr’Arno, Santo Spirito, Brancacci Chapel

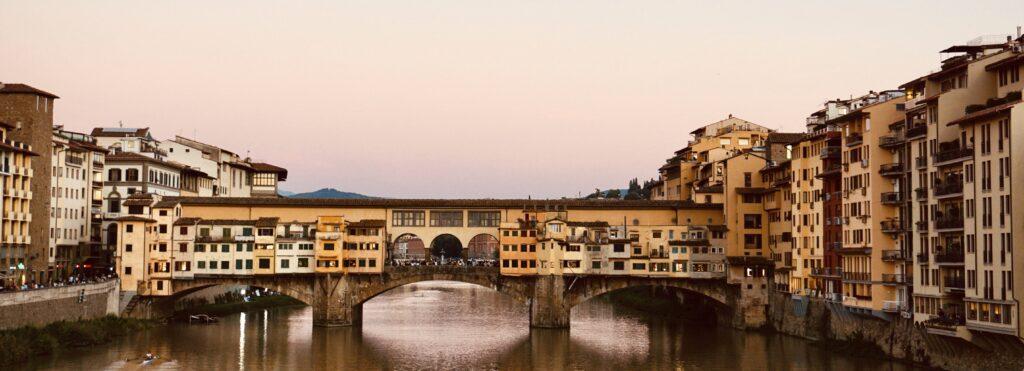

ASCENDING the Lung’ Arno Acciaiuoli, we come to the Ponte Vecchio, the oldest and most picturesque bridge in Florence, built by Taddeo Gaddi, and covered with the shops of the goldsmiths, who were established here by Cosimo I. Above the houses on the left runs the corridor built by Vasari to connect the Uffizi with the Pitti. An open loggia on the middle of the bridge gives beautiful views up and down the river.

Among the four bridges that span the river, the Ponte Vecchio—that bridge which is covered with the shops of jewellers and goldsmiths—is a most enchanting feature in the scene. The space of one house, in the centre, being left open, the view beyond is shown as in a frame; and that precious glimpse of sky, and water, and rich buildings, shining so quietly among the huddled roofs and gables on the bridge, is exquisite. Above it, the Gallery of the Grand-Duke crosses the river. It was built to connect the two great palaces by a secret passage; and it takes its jealous course among the streets and houses, with true despotism; going where it lists, and spurning every obstacle away before it.

Charles Dickens, Pictures from Italy, p. 266.

It was while Cosimo I. was making this passage that he first saw the beautiful Camilla Martelli, daughter of one of the jewellers on the bridge, whom he made his mistress, and afterwards his wife. Her splendours were of short duration. His successor, Francesco, shut her up in the convent of the Murate, where she made herself so disagreeable that the nuns offered Novenas to be relieved of her. The next Grand-Duke removed her to S. Monica, but she was only allowed to come out once for the marriage of her daughter Virginia with the Duke of Modena, and died imbecile from disappointment.

Le nozze sue per gli altrui conforti!

Molti sarebber lieti, che son tristi,

Se Dio t’ avesse conceduto ad Ema

La prima volta ch’ a città venisti.

O Buondelmonte, how in evil hour

Thou fled’st the bridal at another’s promptings!

Many would be rejoicing who are sad.

If God had thee surrendered to the Ema1The palaces of the Amidei by whom young Buondelmonte was slain were in the Por S. Maria between the Via S. Apostoli and the Ponte Vecchio. An Amideo was one of the seven blessed founders of the Servites. Dante speaks of the honour in which this great house was held: —La casa, di che nacque il nostro fleto, / Per lo giusto disdegno che v’ha morti / E posto fine al vostro viver lieto, / Era onorata ed essa, e suoi consorti.

The house from which is born your lamentation. / Through just disdain that death among you brought / And put an end unto your joyous life, / Was honoured in itself and

Dante Paradiso 16:136–139. Trans. Longfellow.

The Mars was replaced by the group of Ajax and Patroclus now in the Loggia dei Lanzi, and its niche is at present occupied by a bronze XVII. c. statue of Bacchus. The fountain falls into an antique fluted bath with ringed lions’ heads.

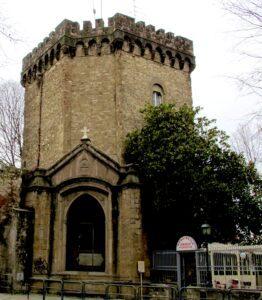

Mannelli Tower, 12th c. Top story of brick subsequent. (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

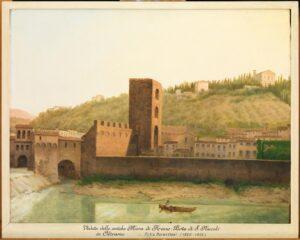

We have now entered the shady part of the town, known as Oltr’ Arno. On our left is the old tower of the Palazzo Mannelli,2The Mannelli, famous in warfare from the XII. c., claim descent from the Manlii of Rome. Arms of Mannelli: Gules, three swords bendwise, argent. where Boccaccio frequently visited his friend and transcriber, Francesco de’ Mannelli. Here (left) is the entrance of the Via de’ Bardi, one of the oldest streets in Florence, but a great part of it has been lately destroyed to make the quay of Lung’ Arno Torrigiani. Among the buildings sacrificed was the interesting chapel of S. Maria sopra l’Arno, which bore an inscription placed there by the handsome young Ippolito Buondelmonte, who, having made a secret marriage with Dianora de’ Bardi, daughter of the hereditary enemy of his house, was surprised in climbing to her chamber by a ladder of ropes, and condemned to death as a robber, which he submitted to rather than betray his wife to the vengeance of her family. On the way to execution he implored to be led for the last time past the Palace of the Bardi, where the lady rushed down and publicly claimed him as her husband. His heroism and her devotion so touched all parties at the time, that peace was restored to Florence for a season. It was from a sarcophagus attached to the wall of this chapel that a priest, who had concealed himself there, rose as a ghost, to terrify a bravo employed by the Duke of Athens.

When, in 1342, the Duke of Athens had ordered the hand of one of his servants to be amputated, Ricci de’ Bardi joined the conspiracy which soon ended in the fall of the tyrant, and the Bardi were rewarded with a third share in the government. They lost this by misuse of their power, but when Bishop Acciaiuoli was sent to announce their exclusion from the government, the Bardi and other nobles barricaded Oltr’ Arno, and were only subdued after a stout resistance.

The Bardi, to whom twenty-three houses in this street formerly belonged, whose tower is still to be seen at No. 62, and a daughter of whose house became the wife of Cosimo de’ Medici, in common with the great bank of the Peruzzi, failed in 1345 (?) for 900,000 florins, lent to Edward III. of England for his invasion of France, and King Peter of Sicily, and which were never repaid. They recovered, however, from these losses.

The Via de’ Bardi extends from the Ponte Vecchio to the Piazza de’ Mozzi at the head of the Ponte alle Grazie; its right-hand line of houses and walls being backed by the rather steep ascent which in the fifteenth century was known as the Hill of Bogoli, the famous stone-quarry whence the city got its pavement—of dangerously unstable consistence when penetrated by rains; its left-hand buildings flanking the river, and making on their northern side a length of quaint, irregularly pierced façade, of which the waters give a softened, loving reflection as the sun begins to decline towards the western heights. But quaint as these buildings are, some of them seem to the historical memory a too modern substitute for the famous houses of the Bardi family, destroyed by popular rage in the middle of the fourteenth century.

They were a proud and energetic stock, these Bardi: conspicuous among those who clutched the sword in the earliest world-famous quarrels of Florentines with Florentines, when the narrow streets were darkened with the high towers of the nobles, and when the old tutelar god Mars, as he saw the gutters reddened with neighbours’ blood, might well have smiled at the centuries of lip-service paid to his rival, the Baptist. But the Bardi hands were of the sort that not only clutch the sword-hilt with vigour, but love the more delicate pleasure of fingering metal: they were matched, too, with true Florentine eyes, capable of discerning that power was to be won by other means than by rending and riving, and by the middle of the fourteenth century we find them risen from their original condition of popolani to be possessors, by purchase, of lands and strongholds, and the feudal dignity of Counts of Vernio, disturbing to the jealousy of their republican fellow-citizens. These lordly purchases are explained by our seeing the Bardi disastrously signalised only a few years later as standing in the very front of European commerce—the Christian Rothschilds of that time—undertaking to furnish specie for the wars of our Edward III., and having revenues “in kind” made over to them, especially in wool, most precious of freights for Florentine galleys. Their august debtor left them with an august deficit, and alarmed Sicilian creditors made a too sudden demand for the payment of deposits, causing a ruinous shock to the credit of the Bardi and of the associated houses, which was felt as a commercial calamity all along the coasts of the Mediterranean. But, like more modern bankrupts, they did not, for all that, hide their heads in humiliation; on the contrary, they seem to have held them higher than ever, and to have been amongst the most arrogant of those grandi who drew upon themselves the exasperation of the armed people in 1343. The Bardi, who had made themselves fast in their street between the two bridges, kept these narrow inlets, like panthers at bay, against the oncoming gonfalons of the people, and were only made to give way by an assault from the hill behind them. Their houses by the river, to the number of twenty-two (palagi e case grandi), were sacked and burnt, and many among the chief of those who bore the Bardi name were driven from the city. But an old Florentine family was many-rooted, and we find the Bardi maintaining importance and rising again and again to the surface of Florentine affairs in a more or less creditable manner, implying an untold family history that would have included even more vicissitudes and contrasts of dignity and disgrace, of wealth and poverty, than are usually seen on the background of wide kinship. But the Bardi never resumed their proprietorship in the old street on the banks of the river, which in 1492 had long been associated with other names of mark, and especially with the Neri, who possessed a considerable range of houses on the side towards the hill.

George Eliot, Romola, vol. 1, pp. 59–61.

Palazzo Mozzi (detail), 13th c. (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

In Piazza de’ Mozzi, the Palazzo Mozzi,3Arms of Mozzi: or, a cross lozengy, gules, with the motto “Pax.” They were Papal bankers. with beautiful gardens at the back, and bay-trees at side, belonged to a rich family, one of whose members wrote in the name of his country to refuse to surrender the Venus de’ Medici to Napoleon I. The Mozzi, the most powerful Guelphic family of Oltr’ Arno, in the XIII. c. extended their hospitality to Gregory X. in 1273; to Cardinal Latino in 1280; to Pietro, brother of King Robert of Naples, in 1314; to Gualtiero, Duke of Athens, in 1326. They also gave four gonfalonieri and seven priori to the Republic. The word Pax, which they were permitted by the Pope to inscribe on their arms, had reference to the treaty between the Guelphs and Ghibellines (broken four days later), which was made at their palace in 1273, and in memory of which the adjoining, and now destroyed, church of S. Gregorio della Pace was erected. The stemma on the angle of the palace bears Medici impaling chequy for Uberti (?).

In 1881 the art collector and dealer, antiquarian, art restorer, and one-time companion to Garibaldi, Stefano Bardini (1836–1922) purchased San Gregorio della Pace and transformed the ancient church into a luxurious palazzo and studio, now the Museo Stefano Bardini. The museum opened in 1923 and includes an eclectic collection of objects including Tino di Camaino’s beautiful Charity, 1311–23), a sarcophagus with the three faces of the Trinity by Pagno di Lapo Portigiani, 1449–52, and Pietro Tacca’s Porcellino, 1633, a copy of which is in the Mercato Nuovo. Bardini also purchased the Mozzi Palaces and gardens, which his son Ugo inherited and subsequently bequeathed to the Italian State in 1996.

Over the arch leading to the Costa S. Giorgio is the Palazzo Tempi (now Bargagli), a restoration of the house of Amerigo dei Bardi, head of the great family. The Palazzo Capponi, No. 28, on the left of the street, was the residence of Niccolò d’ Uzzano (1350–1433), three times Gonfalonier, who long resisted the power of the Medici. His mother was a Bardi. His daughter and heiress, Ginevra, married a Capponi. He lies in S. Croce. The palace has frescoes by Poccetti and Furini, and a porphyry lion by Donatello stands at the foot of the staircase. [The arms are: per bend, argent—sable.] Just beyond is (Nos. 22–24) the Palazzo Giugni-Canigiani, originally built in 1283, and once the Hospital of T. Lucia. Here Eletta de’ Canigiani, the mother of Petrarch, was born. Its court has a Madonna by Luca della Robbia, and its columnar staircase and well are most picturesque. It contains several good pictures, including a Nativity by Filippino Lippi. The adjoining church of S. Lucia de’ Magnoli, founded 1078, is named from an extinct wealthy family, and contains a Virgin with angels, a fine work of Giovanni della Robbia, over the door. Near this church the great family of the Alamanni had houses from the XII. c.

Baccio and Domenico d’Agnolo, Palazzo Torrigiani, c. 1540- (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Beyond this, at the entrance of the Ponte alle Grazie, is the vast and handsome Palazzo Torrigiani,4Torrigiano di Guido d’Orlando was Prior in 1303, and between that date and 1462 there were no fewer than eleven Priors of the family. Arms of Orlandi: Gules, a tower argent between two stars, or. built by Baccio d’ Agnolo for the Nasi. It was the insult offered by Giuliano Salviati to Luisa Strozzi at a masked ball here (1534) which began the feud between the Medici and Strozzi.

The palace once contained a good collection of pictures now sold and scattered to museums worldwide including the Prado in Madrid, Louvre in Paris, National Gallery in London, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

The garden may be visited on application.

The Torrigiani have been established in Florence from the XIV. c. Cardinal Luigi Torrigiani (1777) was Secretary of State under Clement XIII., and at present the family holds one of the highest places amongst the Florentine nobility. The present Marquis was Sindaco of Florence.

Lorenzo Bartolini, Monument to Nicola Demidoff, begun 1830 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Campanile S. Niccolò sopra l’Arno (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Piazza Demidoff, in front of the palace, contains a monument by Bartolini to Prince Niccolò Demidoff, a great benefactor of Florentine charities, who lived in the opposite (rebuilt) Palazzo Serristori, where in 1530 the treacherous Malatesta Baglioni was lodged.5The Serristori were influential partisans of the Medici. Arms of Serristori: Azure, a fess argent between three stars, two and one, or. Close to the end of the piazza is the Church of S. Niccolò sopra l’Arno, before which the citizens assembled in 1529 to swear to defend the Republic. It was in the belfry of this church that Michelangelo is related to have hidden himself after the city was betrayed to the Imperialists, till Clement VII. had promised to pardon him for having constructed the fortifications. The church contains four saints ascribed to Gentile da Fabriano. In the sacristy is an injured fresco of S. Thomas receiving the Cintola, by Ridolfo Ghirlandajo (1483–1560). This was one of the earliest-built churches in Florence, and originally belonged to S. Miniato.

The Porta S. Niccolò is the only one of the Florentine gates which retains its three tiers of arches. Its battlements were formerly worked out on brackets. The lunette fresco of the Madonna, Child, and Saints on the inner side, dates from 1357. By this gate we reach the noble Villa Fenzi, built by Luca Pitti from designs of Brunelleschi. Trollope lived and wrote at Rusciano close by. There is a glorious view of the city from the villa terrace. The Badia a Ripoli, an abbey which belonged to Vallombrosan monks, has frescoes by Poccetti. At Bagno a Ripoli the tram stops.

••••••••••••

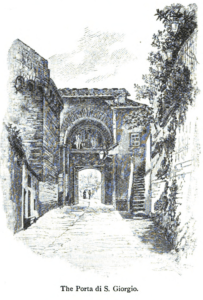

From near the entrance to the Via de’ Bardi from Piazza dei Mozzi, a passage under an archway leads up the hillside, by a steep ascent—Costa Scarpuccia, where S. Catherine of Siena stayed on her way to Avignon—to the Porta S. Giorgio (named from a neighbouring church), passing, on the right, the house (No. 13) inhabited by Galileo; in the garden is his sundial. The very picturesque gate dates from 1324, and bears a fresco by Bernardo Daddi of the Virgin and Child throned, with S. George and S. Sigismund. The neighbouring Fortezza di S. Giorgio, or Belvidere, was built by Buontalenti for Ferdinando I. in 1590. The Duke kept his treasures in a secret chamber beneath it. A little beyond the gate is the Church of S. Leonardo, which contains several pictures by Neri de’ Bicci and a curious romanesque ambone which was removed hither by the Grand-Duke Leopold from the destroyed Church of S. Piero Schieraggio, to which it is said to have been brought from Fiesole: S. Antonino used to preach from it.

From near the entrance to the Via de’ Bardi from Piazza dei Mozzi, a passage under an archway leads up the hillside, by a steep ascent—Costa Scarpuccia, where S. Catherine of Siena stayed on her way to Avignon—to the Porta S. Giorgio (named from a neighbouring church), passing, on the right, the house (No. 13) inhabited by Galileo; in the garden is his sundial. The very picturesque gate dates from 1324, and bears a fresco by Bernardo Daddi of the Virgin and Child throned, with S. George and S. Sigismund. The neighbouring Fortezza di S. Giorgio, or Belvidere, was built by Buontalenti for Ferdinando I. in 1590. The Duke kept his treasures in a secret chamber beneath it. A little beyond the gate is the Church of S. Leonardo, which contains several pictures by Neri de’ Bicci and a curious romanesque ambone which was removed hither by the Grand-Duke Leopold from the destroyed Church of S. Piero Schieraggio, to which it is said to have been brought from Fiesole: S. Antonino used to preach from it.

On the left of the street—Via Guicciardini—which continues from the Ponte Vecchio, is the Piazza S. Felicità, where a granite column commemorates one of the murderous victories of S. Peter Martyr over the heretics called Paterini. His statue formerly crowned the column. Amongst his chief supporters were the Dei Rossi, who had a palace here and gave its former name to the piazza. The tribune of the rebuilt (1736) Church, in which young Buondelmonte was married to Fina Donati, belongs to the Guicciardini, and the historian Francesco Guicciardini is buried in front of the high-altar.6Arms of Guicciardini: Azure, three hunting horns, argent, slung, gules. The first chapel on the right (Capponi) contains a Deposition, by Jacopo Pontormo; in the 5th chapel is a Madonna with Saints, by Taddeo Gaddi. In the sacristy is a picture of the Martyrdom of S. Felicità and her seven sons, attributed to Neri de’ Bicci. In the chapter-house are frescoes, by Cosimo Ulivelli and Agnolo Gheri, and over the altar a Crucifixion by Niccolò Gerini. Some of the Macchiavelli family are buried in the cloister, where their arms (argent, a cross azure, between four spears azure) are seen. Outside the portico of the church are some monuments from an early Christian cemetery which existed here. In the porch is the incised figure of Barduccio Barducci, ob. 1414, who was twice Gonfalonier, and an altar-tomb with a figure of Cardinal Luigi de’ Rossi, 1519, by Raffaelle di Montelupo. A monument to Arcangela Paladini, artist, musician, and court singer, who died in 1600 at the age of twenty-three, was erected by the Grand Duchess Maria Maddalena, with a bust by Bugiardini. During the XVII. and XVIII. c. the church served as the Grand Ducal chapel. Ferdinand I. made a court gallery there, which he could enter with his family from the passage leading from the Pitti to the Uffizi.

Now, on the left, we reach the Palazzo Guicciardini (No. 17), nearly opposite to which a tablet marks the modernised house (No. 16) where Macchiavelli was born, lived, and died. The Guicciardini gave no fewer than 16 gonfalonieri and 44 priori to the State. Their most illustrious member was Francesco, 1482–1570, author of the Istorie Fiorentini, of whom the palace contains a fine portrait by Bugiardini. The next houses belonged to Benizzi, as once did these, and an inscription on No. 17 relates here of the founder of the Serviti San Filippo (1233).

Before the entrance (right) of the Via Maggio, on the right, a tablet on the wall of Casa Guidiis inscribed to the memory of an English poetess, who lived there for many years with her distinguished husband, and died there in 1861—“Elizabeth Barrett Browning, che in cuore di donna conciliava scienza di dotto e spirito di poeta, e fece, del suo verso aureo anello fra Italia e Inghilterra.” [Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who in the heart of a woman reconciled the science of a scholar and the spirit of a poet, and made her golden verse a link between Italy and England] She is buried in the Protestant cemetery.

The Casa Guidi is almost opposite to the Pitti Palace, which is considered in a separate section.

We are in Piazza Pitti, in a charmed circle of sun-blaze. Our rooms are small, but of course as cheerful as being under the very eyelids of the sun must make everything.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Letters, vol. 1, p. 354.

The Via Maggio begins with the Piazza S. Felice and the conventual church of S. Felice, containing: —

Right:

6th Altar. Ridolfo Ghirlandajo. Madonna and Saints.

7th Altar. L. Giovanni di S. Giovanni. A fresco of S. Felice succouring S. Massimo, when he was dying of hunger.

Left:

6th Altar. Neri de’ Bicci. A triptych, also a Madonna which is said to have wrought miraculous cures during the plague of Florence.

5th Altar. Jacopo da Empoli. Madonna presenting S. Hyacinth to the Holy Child.

The Abbé Basilio Nardi (1542), for thirty years soldier of the Republic; Sustermanns the painter; Piamontini the sculptor; the architects Parigi; Count Tyrrel, the friend of the Grand Duke Gian-Gastone; and Gabbriani the painter, 1726, are buried in this church.

On the right of the Via Maggio, which we will now follow, turning toward the river, is a house, No. 37—at the corner of the Via Marsili—painted in fresco by Poccetti, where Bernardo Buontalenti lived, and whither Tasso rode from Ferrara to thank him for having contributed to the success of his “Aminta” by the scenery he had painted for it.

A few days after the recitation of the comedy, Bernardo was returning, as was his wont, to dine at his house in the Via Maggio; on approaching the door, he saw a man of good condition, venerable in person and appearance, in a country dress, dismount from his horse as if to speak to him. Buontalenti waited civilly till the stranger came up and said, “Are you that Bernardo Buontalenti, so celebrated for the wonderful inventions which are daily produced by your genius, and who in particular have composed the astonishing scenery for the “Aminta” by Tasso which has lately been recited?” “I am Bernardo Buontalenti,” he answered, “but indeed am not such as your kindness and courtesy is pleased to believe me.” Then the unknown, with a smile, flung his arms round his neck, kissed him on the forehead, and said, “You are Bernardo Buontalenti, and I am Torquato Tasso. Addio, addio, my friend, addio;” and, without leaving the astonished architect (who was quite thrown off his balance by this unexpected meeting) a moment to recover himself sufficiently either for words or deeds, he mounted his horse and galloped off, and was not seen again.

Filippo Baldinucci, Opere, vol. 8, pp. 62–63.

The Via Michelozzi, on our left, leads to Piazza S. Spirito. In it is a fine Palace of the Michelozzi,7Arms of Michelozzi: per bend sinister, argent-gules, counterchanged, six monti gules, and a star, or. a fourteenth-century family, and partisans of the Medici.

Farther down the street (No. 15) is the Palazzo of the Ridolfi family,8Arms of Ridolfi: azure, a mount or, and over all a bend gules. of whom 21 were Gonfaloniers and 52 were Priors. It contains a Madonna by Filippo Lippi. No. 28 belonged to Count Angiolo D’Elci, a former collector of Rariora editions, which he left to the Laurenziana. The house bears a fine shield, a double-eagle crowned, and holding in its claws a lamb (?).

At No. 26, with the façade “sgraffito,” bearing a hat (cappello) and some shops in ground-floor, lived the famous Venetian Bianca Cappello, wife of Francesco de’ Medici, who bought this palace and the Rucellai Gardens for her. (See her two portraits by A. Allori and Bronzino, and her cameo in the Gem Room in the Uffizi Gallery.) She lived with her first lover, Pietro Buenaventura, opposite S. Marco, after their flight from Venice, and was first seen there by Duke Francesco. Pietro, to whom the Duke gave employment, was murdered farther down the street toward the Bridge, certainly by some one jealous of him, or else afraid of him. It is not astonishing that the murder was laid at the Duke’s door: yet that might well have been foreseen by the assassin.

Bianca summoned from Venice her brother, Vittorio, to join her in Florence, and he soon became the sole adviser and favourite of Francesco, which so much excited the jealousy and hatred of the Medici family that every means was employed to oblige Francesco to dismiss Vittorio from his court. The dismissal, however, did not satisfy the enemies of the Grand Duchess (Bianca), who were resolved on her death; and one evening after she and the Duke had partaken of supper at their favourite villa of Poggio-a-Cajano, both were seized with violent pains and died within a few hours of one another.

Susan and Joanna Horner, Walks in Florence, 1877: pp. 580–581.

Bartolomeo Ammannati, Ponte S. Trinità, 1567-69. Destroyed by German Army in 1944 and rebuilt in 1958. (sig photo)

The next two palaces are Del Turco, and Michelozzi (as the coat-of-arms shows), now Amerighi. This brings us to Ponte Trinità and the Fresco-Baldi Palace on our right adjoining the river, adorned with Medici busts by the former monks of San Jacopo, to whom it had been given. It is now a school for training female teachers. The Frescobaldi were of Teutonic origin. We find them transacting business with Henry III. early in the thirteenth century.

Opposite is the Palace of Piero Capponi, the patriotic hero, who destroyed a Treaty designed to lay Florentine liberty beneath the feet of Charles VIII. of France. He fell in battle before Pisa, 1496.

No. 7 is the Palazzo Firidolfi, belonging to a family noted in the defence of Florence against Dante’s Emperor, Henry VII., in 1312; it contains a fine library and a chapel painted by Vasari. The Via Velluti commemorates another early and important family who figured with 29 Priors and 7 Gonfaloniers. It leads to the Via Toscanella, where an ancient well marks the site of the “darksome, sad, and silent house” where Boccaccio was born, and in which he lived with his “old, cold, rugged, and avaricious father.”9See Boccaccio in the Ameto, 1343.

____________________________

At 19 Via Romana (west of the Pitti Palace) is the Museo di Fisica e di Storia Naturale.

Gherardo Silvani, Campanile of S. Jacopo sopr’ Arno (sig photo)

Turning east, however, to complete our round, we re-enter the Via di S. Jacopo. On the left, with a portico of three bays with black marble columns, is the very ancient Church of S. Jacopo sopr’ Arno, rebuilt in 1580. It contains a copy, by Giov. della Robbia, of the group of the Doubting S. Thomas by Verrocchio. The cupola was built by Brunelleschi, whilst experimenting for his famous cupola of the duomo. The choir is a beautiful XVI. c. work. The painter Starnini, the master of Ghiberti, is buried here. The little campanile, which is so picturesque a feature when seen from the other side of the river, is by Gherardo Silvani. In this church the nobles, under Berto Frescobaldi, assembled in 1293, and determined to resort to arms rather than submit to the decree which excluded them from a share in the Government.

Opposite this (No. 17) is the fine old Tower of the Ramagliati adorned in 1830 with an Annunciation with kneeling angels, a work of Luca del la Robbia. At No. 77 is the Palazzo Novellucci, with a picturesque little courtyard.

______________________________________

Santo Spirito 18th c. Façade (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

If we cross the Via Maggio with Ponte S. Trinità on our right and take Via del Presto it will bring us at once to S. Spirito.

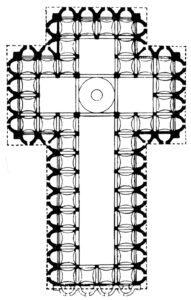

Originally built by Augustinians in 1292, in 1433 a new church, designed by Brunelleschi, was begun alongside of it. It was still unfinished in 1471, when the old church took fire from some illuminations in a miracle play intended to represent the descent of the Holy Ghost upon the Apostles, during the visit of Galeazzo-Maria Sforza, and was entirely burnt. The completion of the new edifice was therefore hastened. This church is the purest in proportions in Florence. The cupola is by Salvi d’ Andrea, and the bell-tower by Baccio d’ Agnolo is a good example of the renaissance working upon the mediaeval Campanile.

Santo Spirito being entirely according to Brunelleschi’s design, he was enabled to mould it to his own fancies. This church is 296 feet long by 64 feet 3 inches wide, and, taking it all in all, is internally as successful an adaptation of the basilican type as its age presents.

James Fergusson, History of the Modern Styles of Architecture, p. 41.

Filippo Brunelleschi, Santo Spirito Nave (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Plan of Santo Spirito (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The interior is exceedingly handsome, though most of the pictures are third-rate. Under the dome, which is suspended over the crossing, is a baldacchino, much like that at S. Alessio at Rome, and around it a choir, of 1599, isolated, as in the Spanish churches. The vast number of chapels contain many pictures:

R. Aisle:

1st Chapel. Piero Franceso [sic] Toschi. Assumption.

2nd Chapel. Nanni [sic] di Baccio Bigio. Copy of the Pietà of Michelangelo.

West Transept (right):

2nd Chapel, on right. Pollajuolo. (?) S. Monica enthroned.

3rd Chapel, at end. Filippino Lippi. Madonna and Child with saints, and Tanai de’ Nerli, the persecutor of Savonarola, and his wife, the donors, kneeling. This picture is a worthy companion to that at the Badia.

4th Chapel, at end. Copy of the Munich Perugino. The Vision of the Virgin to S. Bernard.

Bernardo Rossellini, Monument of Gino Capponi, 1450s (photo via Europeana)

1st Chapel, left (returning}. Monument of Gino Capponi, his son Neri, and his great-grandson Piero, by Bernardo Rossellino.10 Hare credits Simone Ferrucci as the artist.

Among many disasters, no one appeared so great, no one caused such universal grief, as the death of the brave and generous citizen, Piero Capponi. He had undertaken the siege of the castle of Soiana, to retake it from the enemy; and, as was usual with him, he was acting on this occasion both as common soldier and commander; and, while planting a gun near the wall, he was mortally wounded by a ball. The soldiers fled, as if terror-struck, and raised the siege of Soiana. At Florence a splendid funeral, at the public expense, was immediately ordered, and there never was seen so universal a lamentation for the death of a private citizen. His body was brought up the Arno in a funeral barge, and was deposited in his own house in Florence, near the bridge of the Santa Trinità, from whence it was taken to the Church of Santo Spirito, accompanied by the magistrates and a vast multitude of citizens. The church was lighted up by innumerable tapers, and, in four ranges of banners, the arms of the magistracy alternated with those of the family. A funeral oration was delivered over the coffin, proclaiming with the highest praise the distinguished life of the deceased, and the deep sorrow felt for the loss of the valiant soldier and eminent citizen. His remains were then deposited in the same tomb which his grandfather Neri had caused to be constructed for his illustrious great-grandfather, Gino Capponi.

Pasquale Villari, The History of Girolamo Savonarola, vol. 2, pp. 110–111.

Choir:

2nd Chapel, on right. Agnolo Gaddi. An altar-piece, close to which is the monument of Piero Vettori, a classical satirist, 1499-1565.

4th Chapel, at end. Alessandro Allori. Martyrdoms.

1st Chapel, on left (returning). Botticelli. Annunciation.

East Transept (left):

1st Chapel, at end. Piero di Cosimo. (1482). Madonna enthroned, with S. Thomas and S. Peter.

2nd Chapel of the Corbinelli. Marble work by Sansovino (Andrea Contucci).

Besides the coronation of the Virgin, which forms the top of this immense tabernacle, there is, in the lower part, a representation of the Last Supper, where the apostles are placed in such a way as to multiply the difficulties of the perspective, so that the he artist gave himself the pleasure of triumphing. In these two compositions, the marble is treated in the manner of Mino da Fiesole, that is to say that the figures have very little relief, and that the lines which circumscribe them sometimes seem to merge with the flat surface on which they rest. Besides, the execution is delicate and the feeling admirably rendered. As for the details of ornamentation which belong to decorative sculpture, they are of a perfection which one does not always find to the same degree in the subsequent works of Andrea San Sovino.

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, vol. 1, p. 449.

3rd Chapel, at end. Raffaellino del Garbo. The Trinity, with S. Catherine and S. Mary Magdalen in adoration.

1st Chapel, on left (returning), Piero di Cosimo? Madonna enthroned, with S. Bartholomew and S. Nicholas.

Left Aisle (returning):

Chapel beyond the door. Rid. Ghirlandajo. Virgin and Child, with S. Anna, S. Mary Magdalen, and S. Catherine.

In this church Luther preached on his way to Rome, as an Augustinian canon.

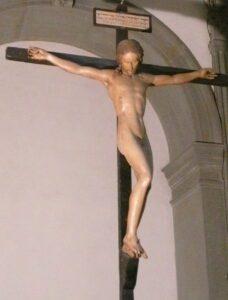

Michelangelo, Crucifix, c. 1792 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

There is a beautiful vaulted passage leading to the Sacristy. Vasari says that Simone del Pollajuolo, called Il Cronaca, was the architect. The octagonal sacristy is by Giuliano di S. Gallo. A Crucifix attributed to the young Michelangelo was discovered in 1963 and is displayed in the Sacristy. The large cloisters are surrounded with unimportant frescoes. Here were wont, at the close of the XIV. c., to hold their learned gatherings the earliest students of Greek literature and adorers of Petrarch, Coluccio Salutati, Fra Luigi Marsili, and Filippo Villani, and to discourse on the glories of Pagan antiquity and the wonders of Rome. A carved poplar wood Crucifix attributed to Michelangelo was discovered in the basilica in 1963 and now hangs from the Sacristy ceiling.

Located in the convent’s former refectory, the Fondazione Salvatore Romano is adjacent to Santo Spirito and dates to the 14th century. The eastern wall contains a fresco by Orcagna.

The Piazza in front of the church is laid out in gardens. At the corner, on the left, stands the old Palazzo Guadagni,11Arms of Guadagni: Gules, a cross engrailed, or. Crest: a unicorn, issuant, argent. an admirable work of the XV. c., with fanali at the angles, and one of the most perfect examples of renaissance palace-work in Florence, consisting of three storeys and an open columnar gallery or Loggia inclosing a fourth, over-browed by a bold roof-cornice. It is the work of Pollajuolo. The lowest, or ground floor, section, retains the small, rectangular barred windows, faithfully indicating the insecurity of the period. The next two storeys, with lofty round-headed windows, were skillfully decorated with a sgraffito frieze apiece, a grey coat with designs on a black ground. The Guadagni, dating from early in the XIII. c., gave eleven gonfalonieri and twenty priori to the republic. Of this family was Bernardo, who played a great part in procuring the exile of Cosimo il Vecchio, who in revenge seized and beheaded his son. Raffaello Romanelli’s memorial statue by in front of the palace honors the pioneering agronomist and politician Cosimo Ridolfi (1794-1865). The Via Michelozzi12Arms of Michelozzi: Per bend arg. gules; six monti beneath a star counter-changed. (named from the family palace in it) opens on the right from the piazza.

The Via del Presto is named from a pawnshop. It was here that Pietro Bonaventura, first husband of Bianca Cappello, was murdered, with the connivance of the Grand-Duke Francesco I., by a nephew of Cassandra Ricci, who was jealous of his being her favoured lover. The Via dei Coverelli takes its name from an ancient family13Arms of Coverelli: Quarterly, 1 and 4, argent 3 bars, wavy, azure; 2 and 3, azure. whose palace and tower it contained.

The Via del Presto is continued to the south by the Borgo Tegolaia, where, at No. 30, S. Filippo Neri lived, as a child, with his nurse.

From the south-west corner of the Piazza S. Spirito, the Via Mazzetta leads to the Via de’ Serragli, which leads to Ponte alla Carraia. The angle of the street and piazza is called Il Canto alla Cuculia, from the cuckoos in the gardens of the Velluti which once existed here. Near its entrance (left) is the house which belonged to the Marchese della Stufa, which contains the wonderful bust of the Gonfalonier Niccolò Soderini, by Mino da Fiesole, and the only authentic portrait of Michelangelo, that by Giuliano Bugiardini, which is described by Vasari.14Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 4, p. 193.

The Via S. Spirito, which runs parallel to the Arno, contains a number of interesting houses. No. 3 still bears the arms of the Vettori15Arms of the Vettori: Per bend, sable and argent, on a bendlet azure semée fleurs-de-lis, or. Crest: 3 ostrich plumes, by Maso da Bartolommeo. No. 4, opposite, also belonged to the Vettori, a family famous from the middle of the XIV. c., and which gave five gonfalonieri and forty-eight priori to the State. They were partisans of the Medici, except the well-known writer Pietro Vettori (1499), who excited the people against them. The house was decorated after the marriage of Maddalena Vettori and Ludovico Capponi, against the will of Cosimo I., and its great hall was afterwards adorned by Poccetti with frescoes representing the illustrious deeds of the Capponi. The palace afterwards belonged to the Riccardi, then to the Leonetti: it was here that the gonfalonier Soderini was imprisoned. No. 5 was the Palazzo Machiavelli, No. 6 the residence of the Segni16 Arms of Segni: Azure, a fess or, with 3 roses. a family which had forty-two priori, and to which Bernardo, the historian of Florence, belonged.

Nos. 11–13 is Palazzo Frescobaldi, and contained a good collection of pictures. No. 15, which belonged to the Pitti, has frescoes by Poccetti. In No. 34–36 was born the famous champion of Florentine freedom, Francesco Ferrucci, murdered by Fabrizio Marmaldo after the battle of Gavinana. Nos. 31–33 is the Palazzo Rinuccini, built by Cigoli and Silvani: its door bears the arms of the Pecori,17Arms of Pecori: Or, a sheep, rampant, browsing the twigs of a tree recurved. its former owners.

The Via de’ Serragli, in which we were just now, which leads in a direct line from the Ponte alla Carraja to the Porta Romana, takes its name from a noble family,18Arms of Serragli: Per pale, a barry of five, or and gules, counter-changed. of Genoese origin, which gave six gonfalonieri and twenty-two priori to the State. Here, No. 6 (left), is the Palazzo Magnani-Ferroni, built from designs of Zanobi del Rosso. No. 5 is the Palazzo Antinori. Beyond, on the left, are the palaces of the Serragli family, then come those of the Salviati, who produced twenty-one gonfalonieri and forty-three priori, and of whom was the famous Archbishop of Pisa, who took part in the conspiracy of the Pazzi against the Medici. The second street which crosses the Via de’ Serragli is the Via della Chiesa, where No. 93, the house of Conte Galli-Tassi, contains a curious picture of the seventeen children of Agnolo Gaddi, by Lorenzo Lippi. At No. 101 Via de’ Serragli is the Teatro Goldoni, on the site of the Convent of Annalena, named from its foundress, the unhappy widow of the great captain Baldaccio d’ Anghiari, murdered in the Palazzo della Signoria, through the jealousy of Cosimo il Vecchio and the schemes of Orlandini, the Gonfalonier, whose advances had been repelled by his beautiful and virtuous wife. The child Giovanni de’ Medici, afterwards the father of Cosimo I., disguised as a girl, was hidden in this convent in 1494.

The Church of S. Elisabetta occupies the site of a house in which S. Filippo Neri was born in 1515. On the left, near the south end of the street, are the Torrigiani Gardens, which contain a high tower, in allusion to the crest of the family. The neighbouring Convento della Calza (so called from the stocking-like material of the cowl worn by its monks) contains a Perugino Crucifixion, with the Beato Columbini of Siena, S. J. Baptist, S. Jerome, S. Francis, and the Magdalen, at the foot of the cross. In the refectory is a Cenacolo by Franciabigio. The Porta Romana, which closes the street, gave the name of Baccio della Porta to Fra Bartolommeo, who lived near it in his youth. The lunette over the inside of the gate is by Franciabigio. The opposite house, at the end of the Via Romana, has a damaged fresco by Giovanni di S. Giovanni, and a tablet in the Via Porta Romana commemorates the birthplace of the artist. He was buried in the little church of S. Pietro di Ser Umido (named from its builder, a poor man who lived by the sale of old iron), where the hunting-horn of S. Hubert was preserved, which was supposed to have the power of curing the bite of a mad dog.

Turning back down the same Via de’ Serragli we reach on the left the Via S. Monaca, which leads to the Carmine, containing the convent founded by the Bardi, in which Cammilla Martelli, the unhappy wife of Cosimo I., took refuge and died. At No. 2 is a tabernacle by Lorenzo de’ Bicci, 1427. The cross street, Via d’Ardiglione, contains, at No. 34, the birthplace of Fra Filippo Lippi.

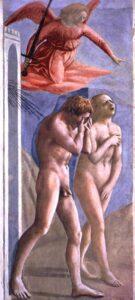

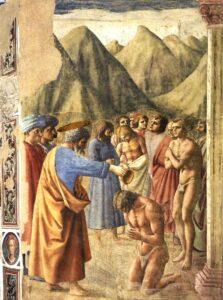

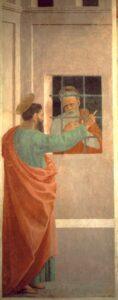

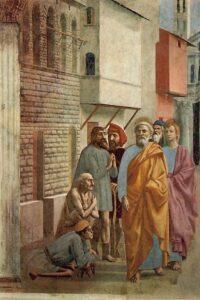

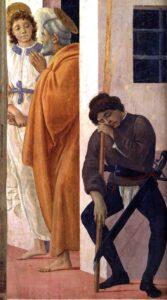

The Church and Convent of the Carmine were built c. 1475, in the place of an older church, whose bells were rung to summon (1378) the rising of the Ciompi. The church was burnt in 1771. In the right transept is the famous Cappella Brancacci, which is covered with noble frescoes, including the finest paintings of Masolino and Masaccio, and some of Filippino Lippi. Here Michelangelo used to study drawing with Piero Torrigiani.

The importance of these frescoes arises from the fact that they hold the same place in the history of art during the fifteenth century as the works of Giotto in the Arena Chapel at Padua hold during the fourteenth. Each series forms an epoch in painting from which may be dated one of those great and sudden onward steps which have in various ages and countries marked the development of art. The history of Italian painting is divided into three distinct and well-defined periods: by the Arena and Brancacci Chapels, and the frescoes of Michelangelo and Raffaelle in the Vatican.

A. H. Layard, The Italian Schools of Painting, vol. 1, p. 141.

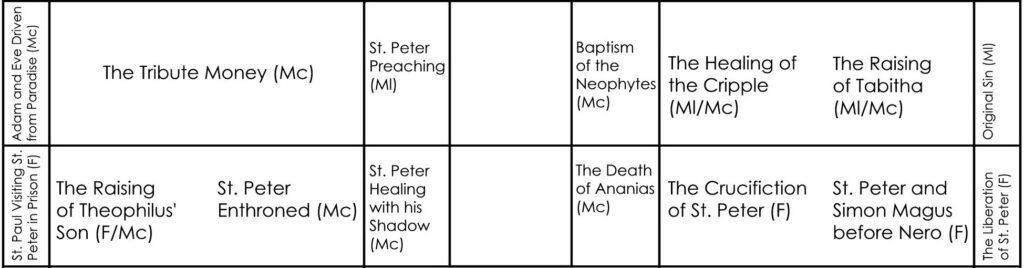

The order of the frescoes, which are in three sections, is: —

Upper Row starting from Left:

Lower Row starting from Left:

In these works, for the first time, we find a well-grounded and graceful delineation of the nude, which, though still somewhat constrained in the figures of Adam and Eve, exhibits itself in successful mastery in the Youth preparing for baptism; so well, in short, in both, that the first were copied by Raffaelle in the Loggie of the Vatican, while the last, according to an old tradition, formed an epoch in the history of Florentine art. The art of raising the figures from the flat surface, the modelling of the forms, hitherto only faintly indicated, here begin to give the effect of actual life. In this respect, again, these pictures exhibit at once a beginning and successful progress, for in the Tribute-Money many parts are hard and stiff; the strongest light is not placed in the middle, but at the edge of the figures; while in the Resuscitation of the Boy, the figures appear in perfect reality before the spectator. Moreover, we find a style of drapery freed from the habitual type-like manner of the earlier periods, and dependent only on the form underneath, at the same time expressing dignity of movement by broad masses and grand lines. Lastly, we reach a peculiar style of composition, which in the Resuscitation of the Boy, supposed to be Masaccio’s last picture, exhibits a powerful feeling for truth and individuality of character. The event itself includes few persons: a great number of spectators are disposed around, who, not taking a very lively interest in what is passing, merely present a picture of sterling, serious manhood; in each figure we read a worthy fulfilment of the occupations and duties of life.

Franz Theodor Kugler, Handbook of Painting:The Italian Schools, vol. 1, p. 195.

What first strikes one is that they all set out from the real, that is to say, from the living individual as the eyes behold him. The baptized young man whom Masaccio shows naked, shivering as he comes out of the water, is a contemporary bather who has taken a dip in the Arno on too cold a day. And likewise his Adam and Eve driven from Paradise are Florentines whom he has undraped, the man with slim thighs and blacksmith’s shoulders, the woman with a short neck and clumsy form, and both with ugly-shaped legs: they are artisans or ordinary people who have not led, like the Greeks, a naked existence, and whose bodies have not been fashioned by gymnastics. Similarly again the resuscitated child by Lippi, kneeling before the apostle, has the meagre boniness and spindling limbs of a modern infant. And, finally, almost all the heads are portraits; two cowled friars on the left of St. Peter are monks leaving their convent. We know the names of the contemporaries who loaned him their heads: Bartolo di Angiolino Angioli, Granacci, Soderini, Pulci, Pollaiolo, Botticelli, Lippi, himself; so that this art seems to have owed its being to surrounding life, as plaster applied to the face repeats the modelling of the forms it is subjected to.

Hippolyte Taine, Italy: Florence and Venice, pp. 124–125.

Se alcun cercasse il marmo, o il nome mio;

La chiesa è il marmo, una cappella è il nome.

Morii, che Natura ebbe invidia, come

L’arte del mio penello uopo e desio.

This church shall be the marble—and the name,

Yon oratory holds it. Nature envied

My pencil’s power, as Art required and loved it—

Thence was it that I died.

In this chapel wrought

One of the few, Nature’s interpreters,

The few whom Genius gives as lights to shine,

Masaccio; and he slumbers underneath.

Wouldst thou behold his monument? Look round!

And know that where we stand, stood oft and long,

Oft till the day was gone, Raffaelle himself;

Nor he alone, so great the ardour there,

Such, while it reigned, the generous rivalry;

He and how many as at once called forth,

Anxious to learn of those who came before,

To steal a spark from their authentic fire,

Theirs who first broke the universal gloom,

Sons of the morning.

Samuel Rogers. Italy: A Poem, pp. 102–103.

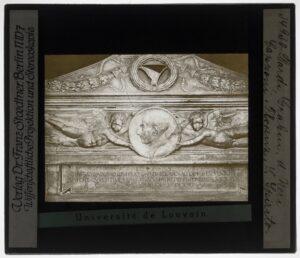

Benedetto Rovezzano, Tomb of Piero Soderini, 1510 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

In the Sacristy of the Carmine are frescoes of the life of S. Cecilia, by Agnolo Gaddi.

In the choir is the restored tomb to the gonfalonier, Piero Soderini (who died in exile and was buried at Rome in 1513), by Benedetto da Rovezzano. It was because this Soderini was simple and had a good heart that Macchiavelli wrote the famous epigram: —

L ‘alma n’ andò dell’ inferno alla bocca;

E Pluto le gridò: Anima sciocca,

Che inferno? va nel limbo de’ bambini!

His soul flew down unto the mouth of hell:

“What? Hell for you? You silly spirit!” cried

The fiend: “your place is where the babies dwell!”

J. A. Symonds, Renaissance in Italy: The Age of the Despots, p. 297.

In the N. transept (1675) is the tomb of S. Andrea Corsini, and great reliefs, by Foggini, relating to his life. Andrea Corsini was a Carmelite monk, Bishop of Fiesole, canonised by Urban VIII. in 1629. His vestments are preserved here.

In the Cloisters are remains of a fresco of the consecration of the church by Masaccio. Little is visible but the figure of a man in a yellow dress, supposed to represent Giovanni de’ Medici: above are traces of a fresco of hermits sitting before their cells. Another fresco, on the same wall, representing a knight and a nun presented to the Virgin by their patron saints, is attributed to Giovanni da Milano.

In the second cloister a Pietà signed “Hieronimus de Brixia, 1504,” is interesting as the work of a rare artist, the Brescian Carmelite Girolamo d’ Antonio.

The Via del Leone, west of the Piazza del Carmine, leads to the Porta S. Frediano, which dates from 1324. Here the Beata Paola in 1363 beheld S. John blessing Florence, a blessing which is supposed to have resulted in the victory of Cascina (1364). Through it the wretched throng of Pisan prisoners was driven; and here Charles VIII. entered Florence, Nov. 17, 1494. Between this gate and the Porta Romana is the old Jewish Cemetery. The bare, domed Church of S. Frediano in Castello was built by Ferri in 1680. The original convent of S. Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi stood here; the cell of the saint is now a chapel.

Between the Porta S. Frediano and the Ponte alla Carraja, the Arno is skirted by the Lung’ Arno Soderini, so called from a family dating from the XII. c., and very illustrious in political life. To it belonged Francesco, the enemy of Cosimo, and Niccolò, who brought about the exile of Piero de’ Medici; Tommaso, immortalised by Poliziano, to whom Piero de’ Medici bequeathed the guardianship of the State; Cardinal Francesco, who conspired against the life of Leo X.; and the famous Piero, the only citizen who was made a perpetual gonfaloniere. The houses on the Lung’ Arno near the bridge all belonged to the Soderini.

From the Ponte SS. Trinità to the Ponte alla Carraja, the southern Lung’ Arno takes the name of Guicciardini19Arms of Guicciardini: Azure, 3 hunting horns, one above another; argent, mouth-pieces; and cords, gules. from the ancient family of that name. Here No. 1 was the Palazzo Capponi, and was the home of the famous Pier Capponi, who, when Charles VIII. threatened the liberties of Florence, exclaimed, “Blow your trumpets, we will ring our bells.” No. 5, built by Baccio d’ Agnolo, was decorated with graffiti by Feltrini. No. 17, now a pension, was a palace of the Soderini, in which S. Catherine of Siena was received by Niccolò Soderini,20Arms of Soderini: Gules, two antlered stags’ heads, argent. during her perilous five-weeks’ visit in 1376, before fetching the Pope from Avignon.

Torrino di S. Rosa, 1324 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

On this occasion the Republic lay under the anathema of Gregory XI. for having flayed alive his nuncio in the streets. War had been declared upon Florence by France, and the infamous Robert, Cardinal of Geneva, was already on his murderous path to Tuscany with Breton troops. Within the city, the Ricci fomented the war-feeling, and therefore set themselves to counteract Catherine’s mission of the olive-branch, which was of course intimately woven with her burning desire to persuade the Pope to end the captivity at Avignon, and come to Rome. The series of frescoes in the Spanish Chapel at S. Maria Novella were just fresh from the artists’ brushes, and she frequently visited the Church, as well as Vol d’ Elsa and Pontorno outside.

Close to the walls is the tower called Torrino di S. Rosa, of 1324. Near the custom-house is a tabernacle belonging to the Cavalieri di S. Stefano, containing a Pietà attributed to Ghirlandajo.