3.1: Piazza della Signoria and Vicinity

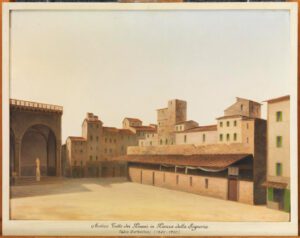

The sunlit Piazza della Signoria12 is the centre of Florentine life and a veritable open-air museum, such as were the Fora in Imperial Rome. Until 1870 it had for 200 years (with a short interval) been called the Piazza del Granduca, but its original designation has now returned to it. On the east is the grand old palace of the Signoria. On the south is the Loggia de’ Lanzi. Opposite is the Palazzo Uguccioni. In the centre are the Fountain of Neptune, and the equestrian statue of Cosimo I. by Giov. da Bologna (1593).

On the west is the imposing Palazzo Lavisan by Giuseppe Landi for the insurance company Assicurazione Generali. Built in a 15th c. revival style that recalls the Palazzi Medici and Pitti, the building consists of nine bays, an arched portone on the ground floor, mezzanine, and three upper stories. Its construction necessitated the destruction of the famous Tetto de’ Pisani, built in 1364 by the 2000 Pisan prisoners, and, though a most characteristic feature, inexcusably destroyed, like the city walls, by the municipality in 1865.

No despot ever sported more cruelly with his slaves than the Florentines with their Pisan prisoners. They were brought in carts to Florence, tied up like bale goods; they were told over at the gates, and entered at the Custom-House as common merchandise; they were then dragged more than half naked to the Signoria, where they were obliged to kiss the posterior of the stone Marzocco (now in the Museo Nazionale), which remains as a record of their shame, and were at last thrown into dungeons, where most of them died.

Joseph Forsyth, Remarks, pp. 43–44.

Close by is the opening to the little street called, after the Della Vacca family, Vacchereccia, in which lived (1420–80) Tommaso Finiguerra, the inventor of niello, and where the brothers Pollajuolo had their workshops. On the north, with the tower of the Badia seen

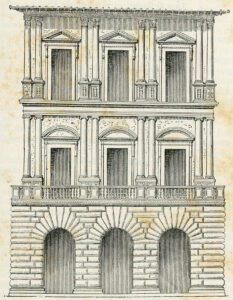

rising behind it, is (No. 6) the beautiful renaissance Palazzo Uguccioni, built by Giovanni Uguccioni in 1550, from designs ascribed to Raffaelle.1Arms of Uguccioni: Gules, a pale crenelly, or. Observe the successive orders of style employed: Rustic, Ionic (coupled columns), and Corinthian. The corner of the palace, till the XVII. c., was originally known as Il Canto dei Guigni, from an old family who had a loggia there. Standing back, and distinguished by the line of shields upon its front (No. 8), is the Palazzo della Mercanzia,2As of 2011 home of Gucci Garden. inscribed, “Omnis Sapientia a Domino Deo est,” [All wisdom is from the Lord God] the former Guild Hall of the Arti Maggiori, where sat an important mercantile tribunal for Assessment of maritime claims. The shields bear the arms of the major and minor “Arti.”

Giovanni da Bologna, Equestrian statue of Cosimo I., 1587-94 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The great Fountain of Neptune is the work of Bartolommeo Ammanati (1571), in whose favour Cellini had been set aside because he had offended the Grand Duke, and Giovanni da Bologna as being too young, though the latter was allowed to undertake the grand Equestrian Statue of Cosimo I., which stands hard by, and which was executed in 1594, twenty years after the death of Cosimo.3This is the best of the four equestrian statues of Giovanni da Bologna. The others were of Henry IV., Philippe II., and Ferdinand I.

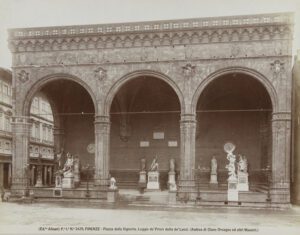

Simone di Francesco Talenti and Benci di Cione, Loggia de’ Lanzi, c. 1376–81

The Loggia de’ Lanzi is so called from the Swiss lancers who were placed here in attendance on Cosimo I. (1541). It was begun in 1376, eight years after the death of Andrea (di Cione) Orcagna, to whom it has been attributed by many writers. Documents prove that it is due to Simone di Francesco Talenti and Benci di Cione: the vaulting is by Angelo de’ Pucci. It was constructed as an open public hall for the meetings and deliberations of the Priors. On the occasion of the burning of Savonarola it was occupied by Franciscans and Dominicans.

I often go out after tea in a wandering walk to sit in the Loggia and look at the Perseus.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Letters, vol. 1, p. 368.

The Loggia consists of four open round arches carried upon graceful composite enriched piers, rising from a lofty stylobate, or platform, gained by five steps from the piazza. It is a felicitous combination of Gothic and Romanesque architecture, and was so much admired in the time of Cosimo I. that Michelangelo proposed the continuation of the colonnade all round the piazza, an idea never carried out on account of the expense. The Grand Duke Ferdinando I. made a terrace-garden on the top of the Loggia, whence the court used to listen to the music in the piazza below. The groups of sculpture between the arches were placed here in the sixteenth century, viz.: —

1. Judith and Holofernes in bronze, cast by Donatello for Cosimo Vecchio, and retained in the palace of the Medici till 1495.4The Judith and Holofernes is no longer in the Loggia dei Lanzi, but is in the Palazzo Vecchio. A copy is located in front of the Palazzo Vecchio. When they were expelled, this group was placed in front of the Palazzo della Signoria, and regarded as a warning to tyrants; hence the inscription, “Exemplum salutis publicae cives posuere.” [Citizens have set a precedent for public safety] In 1560 it was brought to its present position at the head of what had been the Priors’ entrance to the Loggia, for the purpose of the edifice was for the meetings of the Priori. The reliefs at the base are better than the statues.

For the Signoria of Florence,5Vasari is in error. Donatello cast the statue for Cosimo il Vecchio. Donatello cast, in bronze, a statue of Judith cutting off the head of Holofernes. This was placed on the piazza, in an arch of their loggia. It is a work of great excellence, and proves the mastery of the author over his art. There is much grandeur and simplicity in the aspect and vestments of Judith; her greatness of mind, and the power she derives from the aid of God, are made clearly manifest, while the effects of wine and sleep are equally visible in the countenance of Holofernes, as is the result of death in his limbs, which have lost all power, and hang down cold and flaccid. This work was so carefully executed by Donato, that the casting turned out most successfully, and was delicately beautiful: he then finished it so diligently, that it is indeed most wonderful to behold. The basement;, also, which is a balustrade, in granite, of simple arrangement, is very graceful in its effect, and the appearance is extremely pleasing to the eye. Donatello himself was so well satisfied with the whole of this work, that he determined to place his name on it (which he had not done on the others), as is seen in the words Donatelli Opus.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 1, p. 315.

Donatello (copy), Judith and Holofernes, 1455–60

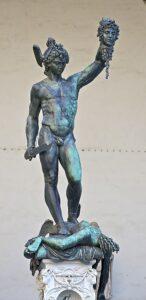

Benvenuto Cellini, Perseus, 1545 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Cellini, Base of Perseus (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

It has something of fascination, a bravura brilliancy, a sharpness of technical precision, a singular and striking picturesqueness which the works of elder masters want. It soars into a region of authentic, if not pure and sublime, inspiration.

J. A. Symonds, Life of Cellini, vol. 1, p. lxxiv.

When we recollect the circumstances attending its casting, the spirit with which the artist, exhausted with fatigue, parched up with fever, leaped from his bed to continue and hasten the melting of the bronze, into which he threw all the pewter vessels of his household, his devout and fervent prayer, his sudden cure, and his joyous repast with all his men, this statue becomes a sort of action reflecting the manners of the time, and the character of the extraordinary man that executed it.

Antoine Claude Valery, Travels in Italy, p. 319.

The pedestal is almost as worthy of study as the statue it supports.6The original pedestal is now in the Bargello and has been replaced with a copy.

Its central portion is occupied by the graceful figure of Andromeda, whose long tresses stream in the wind, as, shielding her eyes with her hand, she looks upward for her deliverer, who is coming down from the clouds to attack the monster, who, with open jaws, bat-like wings, claws of iron strength, and scaly body, stands ready to receive him. Upon the shore are Andromeda’s mother, Cassiopeia, and her father Cepheus, who has a stern, sad face; while between them her disappointed lover Phineas, whose head reminds us of an antique gem, rises from the earth like an avenging spirit, followed by a troop of warriors on foot and on horseback, the last of whom gallop furiously through the clouds.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 2, p. 136.

No one thinks of the pedestal when he has once caught sight of the Perseus. It raises the demigod in air; and that suffices for the sculptor’s purpose. Afterwards, when our minds are satiated with the singular conception so intensely realised by the enduring art of bronze, we turn in leisure moments to the base on which the statue rests. Our fancy plays among those masks and cornucopias, those goats and female Satyrs, those little snuff-box deities, and the wayward bas-reliefs beneath them. There is much to amuse, if not to instruct and inspire us there.7The ornaments of the pedestal, perfectly safe, and much valued here, have recently been carried off to the Bargello and replaced by copies.

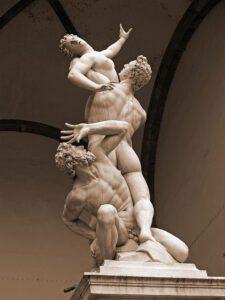

Giovanni da Bologna, Rape of the Sabines, 1583

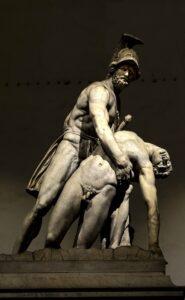

Giovanni da Bologna, Hercules slaying Nessus, 1600

Ajax Supporting the Dying Patroclus (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

John of Bologna, after he had finished a group of a young man holding up a young woman in his arms, with an old man at his feet, called his friends together to tell him what name he should give it, and it was agreed to call it the Rape of the Sabines.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Discourses, pp. 165–66.

It is said that Gian Bologna, when about to model the figure of the stalwart youth represented here, was so struck with the manly proportions of the Conte Ginori, member of a noble Florentine family, whom he happened to meet one morning in a church, that he stared at him fixedly, until the Count asked him who he was and what he wanted. Upon explaining the matter, the Count consented to pose for the figure of the youth, and in return received a present of a bronze crucifix as an acknowledgment of the artist’s gratitude.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 2, p. 173.

Antique Roman Lion, Loggia dei Lanzi (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

At the entrance of the Loggia are two lions, one ancient, from the Villa Medici at Rome, the other an imitation by Flaminio Vacca.

Within, against the rear wall, are several inferior pieces of sculpture; and Thusnelda and five Roman Priestesses from the Villa Medici, to which they were brought from Capranica in 1788; Hercules slaying Nessus, by Giovanni da Bologna, brought from the foot of the Ponte Vecchio in 1838; Ajax supporting the dying Patroclus,8The protagonists in this work, also known as the Pasquino Group, are more commonly identified as Ajax and the dead Achilles or Menelaus and Patroclus. The work, extensively “restored” after a model by Pietro Tacca, is a Roman copy of a Greek original dating from 200-150 BCE. a restoration of a Greek sculpture found in a vineyard near the Porta Portese at Rome, which formerly stood at the farther end of the Ponte Vecchio; and Achilles and Polyxena, a work by Pio Fedi of Florence (1864).

To those who have not been much abroad, it will be sufficient amusement to sit for a time in this beautiful Loggia, if it is only for the sake of watching the variations of the fluctuating crowd in the piazza beneath. The predominance of males is striking. Hundreds of men stand here for hours, as if they had nothing else to do, talking ceaselessly in deep Tuscan tones. Many who are wrapped in long cloaks thrown over one shoulder and lined with faded green, look as if they had stepped out of the old pictures in the palace above.

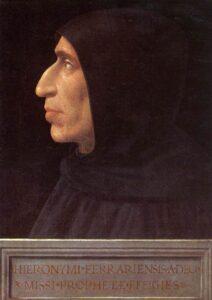

Sitting here, we may meditate on the various remarkable phases of Florentine history of which this piazza has been the scene. Of these, some of the most significant were connected with the story of Savonarola. First came those autos-da-fé for the destruction of worldly allurements, which followed upon his preaching: —

A pyramidal scaffold was erected opposite the palace of the Signory. At its base were to be seen false beards and hair, masquerading dresses, cards and dice, mirrors and perfumery, beads and trinkets of various sorts; higher up were arranged books and drawings, busts, and portraits of the most celebrated Florentine beauties, and even pictures by great artists, condemned, in many instances on very insufficient grounds, as indecorous or irreligious.

Even Fra Bartolommeo was so carried away by the enthusiasm of the moment as to bring his life academy studies to be consumed on this pyre, forgetful that, in the absence of such studies, he could never himself have risen above low mediocrity. Lorenzo di Credi, another and devoted follower of Savonarola, did the same.

John Harford, Life of Michael Angelo, vol. 1, pp. 194–95.

At the Carnival of 1498 there was a second auto-da-fé of precious things which had escaped the inquisitorial zeal of the boy censors. Burlamacchi names marble busts of exquisite workmanship, some ancient, some of the well-known beauties of the day. There was a Petrarch inlaid with gold, adorned with illuminations valued at fifty crowns; Boccaccios of such beauty and rarity as would drive modern bibliographists out of their surviving senses. The Signory looked on from a balcony; guards were stationed to prevent unholy thefts; as the fire soared there was a burst of chants, lauds, and the Te Deum, to the sound of trumpets and the clanging of bells. Then another procession; and in the Piazza di San Marco dances of wilder extravagance; friars and clergymen and laymen of every age whirling round in fantastic reels, to the passionate and profanely sounding hymns of Jerome Beniviene.

Henry Hart Milman, Savonarola, pp. 57–58

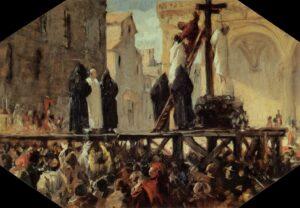

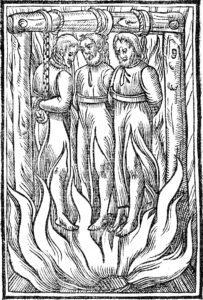

Three tribunals had been erected on the Ringhiera; the next to the door of the Palazzo was assigned to the Bishop of Vasona; the second, on the right of the bishop, to the Pope’s commissioners; and the third, near the Marzocco, was occupied by the Gonfaloniere and the Magnificent Eight. A scaffold had been erected, which occupied about a fourth of the piazza between the Ringhiera and the opposite Tetto dei Pisani. At the end of the scaffold a thick upright beam was fixed, having another beam near the top at right angles, which had been several times shortened to take away the appearance of a cross which it still retained. From this last beam hung three halters and three chains; by the first the three friars were to be put to death, and the chains were to be wound round their dead bodies, which were to continue suspended while the fire consumed them. At the foot of the upright beam was a large heap of combustible materials, from which the soldiers of the Signory had some difficulty to keep off the mob, which pressed round like waves of the sea. When the three friars descended the stairs of the Palazzo, they were met by one of the Dominican friars of Santa Maria Novella, the bearer of an order to take off their gowns, and leave them with their under-tunics only, their feet bare and their hands tied. Savonarola was much moved by this unexpected proceeding; but, taking courage, he held his gown in his hand, and before giving it up he said, “Holy dress, how much I longed to wear thee! thou wast granted to me by the grace of God, and to this day I have kept thee spotless. I do not now leave thee, thou art taken from me.” They were now led up to the first tribunal, and were placed before the Bishop of Vasona. He obeyed the orders he had received from the Pope, but appeared much distressed. Just before pronouncing their final degradation, he had taken hold of Savonarola’s arm, but his voice faltered and his self-possession so forsook him that, forgetting the usual form, in place of separating him solely from the Church militant, he said, “I separate thee from the Church militant and triumphant;” when Savonarola, without being in the least discomposed, corrected him, saying, “Militant, not triumphant; your Church is not triumphant.” These words were pronounced with a firmness which vibrated through the minds of all the bystanders by whom they could be heard, and were for ever after remembered. Being thus degraded and unfrocked, they were delivered up to the secular arm, and by them taken before the apostolic commissioners, when they heard the sentence, declaring them to be schismatics and heretics. After this, Romolino, with cruel irony, absolved them from all their sins, and asked them if they accepted his absolution, to which they assented by an inclination of the head. Lastly, they came before the Magnificent Eight, who, in compliance with custom, put their sentence to the vote, which passed without a dissentient voice. The friars then, with a firm step and perfect tranquillity, advanced to the place of execution. Even Fra Salvestro, at that last hour, had recovered his courage, and, in the presence of death, appeared to have returned to be a true and worthy disciple of the Frate. Savonarola himself exhibited a superhuman strength of mind, for he never for a moment ceased to be in that calm state in which a Christian ought to die. While he and his companions were slowly led from the Ringhiera to the gibbet, their limbs scarcely covered by their tunics, with bare feet and pinioned arms, the most furious of the rabble were allowed to come near and insult them in the most vile and offensive language. They continued firm and undisturbed under that severe martyrdom. One person, however, moved by compassion, came up and spoke some words of comfort, to whom Savonarola with benignity replied, “In the last hour God alone can bring comfort to mortal man.” A priest named Neretto said to him, “In what frame of mind do you endure this martyrdom?” To which he replied, “The Lord has suffered as much for me.” These were his last words. In this universal state of perturbation around them, Fra Domenico remained perfectly composed. He was in such a state of exaltation that he could hardly be restrained from chanting the Te Deum aloud; but, on the earnest entreaties of the Battuto Niccolini, who was by his side, he desisted, and said to him, “Accompany me in a low voice,”—and they then chanted the entire hymn. He afterwards said, “Remember, the prophecies of Savonarola must all be fulfilled, and that we die innocent.” Fra Salvestro was the first who was desired to ascend the ladder. After the halter was fixed round his neck, and just before the fatal thrust was given, he exclaimed, “Into thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit!” Shortly afterwards the hangman wound the chain round his body, and went to the other side of the beam to execute Fra Domenico, who ascended the ladder with a quick step, with a countenance radiant with hope, almost with joy, as if he were going direct to heaven.

When Savonarola had seen the death of his two companions, he was directed to take the vacant place between them. He was so absorbed with the thought of the life to come, that he appeared to have already left this earth. But when he reached the upper part of the ladder, he could not abstain from looking round on the multitude below, every one of whom seemed to be impatient for his death. Oh, how different from those days when they hung upon his lips in a state of ecstasy in Santa Maria del Fiore! He saw at the foot of the beam some of the people with lighted torches in their hands, eager to light the fire. He then submitted his neck to the hangman. There was, at that moment, silence—universal and terrible. A shudder of horror seemed to seize the multitude. One voice was heard crying out, “Prophet, now is the time to perform a miracle!” The executioner, thinking to please the populace, began to pass jokes upon the body before it had ceased to move, and in doing so nearly fell from the height. This disgusting scene moved the indignation and horror of all around, insomuch that the magistrates sent him a severe reprimand. He then showed an extraordinary degree of activity, hoping that the fire would reach the unhappy Friar before life was quite extinct; the chain, however, slipped from his hand, and while he was trying to recover it, Savonarola had drawn his last breath. It was at ten o’clock in the morning of the 23rdof May 1498. He died in the 45th year of his age.

fell from the height. This disgusting scene moved the indignation and horror of all around, insomuch that the magistrates sent him a severe reprimand. He then showed an extraordinary degree of activity, hoping that the fire would reach the unhappy Friar before life was quite extinct; the chain, however, slipped from his hand, and while he was trying to recover it, Savonarola had drawn his last breath. It was at ten o’clock in the morning of the 23rdof May 1498. He died in the 45th year of his age.

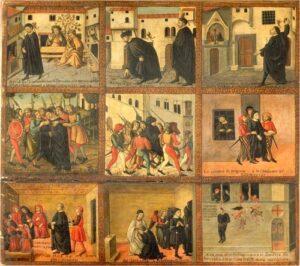

Filippo Dolciati, Execution of Savonarola, Fra Domenico, and Fra Silvestro Maruffi in the Piazza della Signoria, 1498

The executioner had scarcely come down from the ladder when the pile was set on fire: a man who had been standing from an early hour with a lighted torch, and had set the wood on fire, called out, “At length I am able to burn him who would have burned me.” A blast of wind diverted the flames for some time from the three bodies, upon which many fell back in terror, exclaiming, “A miracle! a miracle!” But the wind soon ceased, the bodies of the three friars were enveloped in fire, and the people again closed round them. The flames had caught the cords by which the arms of Savonarola were pinioned, and the heat caused the hand to move; so that, in the eyes of the faithful, he seemed to raise his right hand in the midst of the mass of the flame to bless the people who were burning him.

Pasquale Villari, History of Savonarola, vol. 2, pp. 357–63.

For two centuries the place where Savonarola’s scaffold had stood was strewn with flowers on the anniversary of his death; lamps were kept burning before his picture; scraps of his tunic, ashes from the fire, splinters of the cross, were treasured as relics; portraits were painted and medallions struck in his honour; and numerous apologies for his life were published in the face of the persecution of his enemies. Florence learned too late to regret the great champion of popular freedom when she fell again under the domination of the Medici, and Rome had well-nigh canonised the man whom Rodrigo Borgio burned before the Palazzo Vecchio in 1498.

The Quarterly Review, (July 1889).

Arnolfo di Lapo, Palazzo Vecchio della Signoria, 1299 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Palazzo Vecchio della Signoria, rustic, in three storeys, with a tower, was built for the Gonfalonier and Priors, in whose hands was the government of the Florentine Republic, by Arnolfo di Lapo in 1299. The architect, it is said, was restricted as to size and form by the resolve of the then powerful and fanatic Guelfs that no foot of ground should be used which had ever been occupied by a Ghibelline building, and to which one of that faction might put forward any possible future claim. Arnolfo entreated to trespass upon the open space where the palace of the traitor Uberti had stood, but the authorities resolutely refused—“Where the traitor’s nest had been, there the sacred foundations of the house of the people should not be laid.” It was practically finished in 1313, though much has been added since.

The old palace is a great, bold, irregular mass, beautiful as some rugged natural object is beautiful, and with the kindliness of nature in it.

W. D. Howells, Tuscan Cities, p. 79.

To build the Palace, part of an ancient church was demolished, called San Piero Scheraggio, in which the Carroccio of Fiesole, taken in 1010, was preserved, as well as a beautiful marble pulpit, also brought from Fiesole, which is now in the Church of S. Leonardo in Arcetri, outside Porta San Giorgio. The tower of the Palace of the Foraboschi family was utilised by Arnolfo as substructure for his own tower, which, with its fifteenth century top, is 330 feet high. Its bell bore the name of “La Vacca,” and when it tolled men said “La Vacca mugghia”—“The cow lows,” and forthwith from all quarters the city guilds flocked to the piazza, armed. The Via de’ Leoni, on the east, or back, of the Palace, commemorates the lions which were kept by the city of Florence—as bears are still kept at Berne—partly in honour of William of Scotland, who interceded with Charlemagne for the liberties of the town, partly as a symbol of Hercules, and partly on account of the Marzocco, the emblem of the city. These were maintained in an enclosure called the Serraglio till 1550, when Cosimo I. (requiring more space for the Palace) removed them to S. Marco, and they finally died out in 1777.

Here took place the memorable life-appointment of Walter de Brienne, Duke of Athens, as Ruler of Florence by the rash Priori of 1342.

Within little more than a month after his election the citizens found themselves living under a despotism which soon became a reign of terror. In that short period the Duke had become hateful to well-nigh every citizen. His judges were corrupt, and their sentences ferocious. . . . On the 26th of July the Duke’s Burgundian bodyguard, who were on duty in the Piazza della Signoria, were assailed with showers of stones and other missiles from the tops of the houses, and were easily dispersed. Gianozzo Cavalcanti, mounted on a bench in front of the Palace, tried to raise a cheer in the Duke’s favour and to frighten the armed citizens who were streaming into the piazza, by telling them that they were going to certain death. But all such efforts were fruitless, and by the evening the city was completely in the hands of the people, who proceeded to lay siege to the Palazzo Vecchio, where the Duke had taken refuge. Arrigo Fei, an intimate of the Duke, was taken in the guise of a monk and murdered, and his body was dragged naked through the streets. . . .

In all there were about 400 persons in the building, and, with the exception of some biscuits and wine, they had no food. For three days the Balia were endeavouring to arrange terms between the Duke and the people; but the latter would consent to nothing unless Cerrettieri, Guglielmo d’Assisi, and his son (cruel agents of the Duke), were given up to them. The Duke at first peremptorily refused to accede to any such condition, but his starving soldiery compelled him to do so. No sooner were Guglielmo and his son thrust out of the doors of the Palazzo than they were literally hacked into small pieces by the enraged multitude, whose fury was not allayed until they had actually eaten their victims’ flesh (Villari says some even cooked it!) Cerrettieri de’ Visdomini, who happened to be the last to be ejected, managed, while the crowd were wreaking vengeance on his two companions, to effect his escape. The rage of the people was now so far appeased that they consented to allow the Duke to leave Florence, on his undertaking to renounce all claim to its lordship.

F. A. Hyett, A History of Florence, pp. 130–32.

He left at dead of night, and his arms were torn down from the walls; and all his Acts were repealed.

In 1349 a stone platform was raised against the western façade of the Palazzo, and was called the Ringhiera (aringare, “to harangue”). Hence the Signory always addressed the people, and here it was that the Prior and Judges sate and looked on, May 23, 1498, when —

Savonarola’s soul went out in fire.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Casa Guidi Windows, 1:8.

In 1532 from it Alessandro de’ Medici was proclaimed Grand Duke of Tuscany, and the Signoria closed its days.

Copy of Marzocco by Donatello (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Ringhiera was not removed till 1812. Its northern angle is marked by a copy of the famous Marzocco of Donatello, recently removed to the Bargello. It occupied the place of an older Marzocco erected in 1377. A still earlier Marzocco stood on this site, which the Pisan captives were forced ignominiously to kiss in 1364. The origin of the name Marzocco is unknown.

The lion in mediaeval days seems to have been for Florence what the Wolf of the Capitol was to the Romans—a symbol of her domination; but it was more, for the animal was regarded with superstitious awe. In 1273 a lion was presented to the Commune, which they kept not too carefully in the Piazza S. Giovanni, whence it escaped, filling the city with terror; but it was probably tame, and was caught again near Or San Michele.9The story of Orlanduccio’s rescue by his mother is recounted by the 14th-century Florentine. historian Giovanni Villani. See Giovanni Villani, Selections From the First Nine Books of the Croniche Fiorentine of Giovanni Villani.Westminster: A. Constable & co., 1896, pp. 166–67. Towards 1300 Boniface VIII. gave one to the Priori, which they kept chained in the courtyard of their then palace. One day an ass entering the court became so excited as to back, kicking at the lion, which in spite of help was kicked to death. Villari says it was reckoned to mean the coming downfall of the Church. The birth of lions there was always regarded as a good omen, and was celebrated with public rejoicings. As a matter of fact all republics seem to have looked on this animal as their symbol. Rome at the same period kept one on the Capitol, over whose cage was inscribed: —

The lion in mediaeval days seems to have been for Florence what the Wolf of the Capitol was to the Romans—a symbol of her domination; but it was more, for the animal was regarded with superstitious awe. In 1273 a lion was presented to the Commune, which they kept not too carefully in the Piazza S. Giovanni, whence it escaped, filling the city with terror; but it was probably tame, and was caught again near Or San Michele.9The story of Orlanduccio’s rescue by his mother is recounted by the 14th-century Florentine. historian Giovanni Villani. See Giovanni Villani, Selections From the First Nine Books of the Croniche Fiorentine of Giovanni Villani.Westminster: A. Constable & co., 1896, pp. 166–67. Towards 1300 Boniface VIII. gave one to the Priori, which they kept chained in the courtyard of their then palace. One day an ass entering the court became so excited as to back, kicking at the lion, which in spite of help was kicked to death. Villari says it was reckoned to mean the coming downfall of the Church. The birth of lions there was always regarded as a good omen, and was celebrated with public rejoicings. As a matter of fact all republics seem to have looked on this animal as their symbol. Rome at the same period kept one on the Capitol, over whose cage was inscribed: —

Iratus recole quod nobilis ira leonis In sibi prostratos se negat esse feram.

In anger, recall that the noble anger of the lion tempers its fierceness towards one who is prostrate before him.10Thanks to Professor Tyler Lansford who responded to my inquiry regarding this inscription: “It reads: ‘In anger, recall that the noble anger of the lion / denies that it is fierce towards one who is prostrate before him’ (the version I found reads prostratum, singular). It’s an elegiac couplet (hexameter + pentameter); as often in medieval verse, observance of the meter leads to contorted language. In the second line, I think the sense is: ‘tempers its fierceness’ rather than ‘denies that it is fierce’, which is almost nonsense!”

And Venice kept a live lion, at the same period, in honour both of her dominion and of S. Mark. In Florence the possession led to ridiculous entertainments in honour of illustrious visitors, such as fights between lions and cows and mules, &c., the last of which took place in 1737.

On the left of the entrance to the Palazzo stands a copy of the David of Michelangelo.

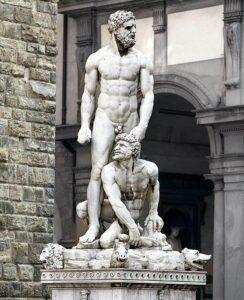

Baccio Bandinelli, Hercules and Cacus, 1546 (photo via Web Galley of Art)

On the right is the Hercules and Cacus of Baccio Bandinelli, executed in 1546 on a block of marble selected by Michelangelo at Carrara, but which he was unable to use, as he was summoned to Rome at that time for his fresco of the Last Judgment. Before reaching Florence, the marble fell into the Arno, and was extricated with difficulty, which caused the Florentine pasquinade, that it had attempted to drown itself rather than submit to the hands of Bandinelli. By the same artist are the two terminal statues called Baucis and Philemon, which were intended to support an iron chain in front of the gate.

Michelangelo had made a model for a Samson with four figures, which would have been the finest masterpiece in the world, but your Bandinelli got out of it only two figures, both ill-executed and bungled in the worst manner. . . . I believe that more than a thousand sonnets were put up in abuse of that detestable performance.

J. A. Symonds, Life of Cellini, vol. 2, p. 400.

The monogram of Christ over the entrance was placed here in 1528 by the Gonfalonier, Niccolò Capponi, at the last moment of Republican life.11Before Florence elected Christ as its King, the seal of the Republic was a naked Hercules leaning on a club, with a lion’s skin over his shoulders.

Palazzo Vecchio Entrance (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

In order to prove his attachment to liberty, he proposed in council that Jesus Christ should be elected King of Florence, a pledge that the Florentines would accept no ruler but the King of Heaven. The contemporary historian, Varchi, describes how the Gonfalonier, when presiding at this great council, February 9, 1527, repeated almost verbatim a sermon of Savonarola, and then, throwing himself on his knees, exclaimed in a loud voice, echoed by the whole council, “Misericordia!” [Mercy!] and how he proposed that Christ the Redeemer should be chosen King of Florence. The old chronicler, Cambi, further relates that on the 10th of June in the following year, 1528, the clergy of the cathedral met in the Piazza della Signoria, where an altar had been erected in front of the palace; the word Jesus was then disclosed before the assembled citizens, who finally accepted Him as their King. The shields of France and Pope Leo were accordingly removed from their place, and the name of the Saviour, on a tablet, was inserted over the entrance to the palace.

Susan & Joanna Horner, Walks in Florence, vol. 1, pp. 266–67.

A room in the tower, discovered in 1814, is supposed to be the Alberghettino, in which the elder Cosimo was imprisoned in 1433, and in which Savonarola passed his last days—save when he was brought down to the Bargello to be tortured. Here the Friar wrote his meditations upon the “In te, Domine speravi” and the “Miserere,” which became famous throughout Christendom.

Edmund Gardner, Story of Florence, p. 154.

From the uppermost or third section of the Palazzo rises a corbelled-out upper storey having round-headed windows and square battlements. Between the deep brackets are seen the coats of arms of the various Gonfalonieri.12Arms of Florence:

1. The earliest consisted of Gules, a lily, argent.

2. A.D. 1252, Argent, a lily, gules. (Guelfic). In Paradiso 16:154, Dante seems to hint at a “dimidiation” *—“né per division fatto vermiglio.” [Nor by division was vermilion made. Longfellow] [* A formation of marshaling by joining the dexter half of one heraldic shield with the sinister half of another divided per pale or sometimes per bend.]

3. Azure, inscribed bendwise Libertas, in golden letters (c. 1298).

4. Azure, two keys or, in saltire, granted to the Guelfs by Clement IV. (1265) for helping Charles of Anjou against Manfred.

5. Azure, an eagle, displayed, or, above a dragon; and in dexter chief a fleur-de-lis, or.

6. Argent, a cross, gules (c. 1294).

7. Azure, semeé fleurs-de-lis, or, with label. Charles of Anjou.

8. Per pale, Barry of seven, or and gules; azure, semeé fleurs-de-lis.

Beneath this the huge walls are all of rock-like grey rustic work, giving the impression of stern impregnability. From those battlements are often said to have been hung the bodies of the Pazzi and their accomplices in the murder of Giuliano de’ Medici in 1478, Archbishop Salviati among them; but this really took place at the windows of the Palace of the Bargello, or Capitano, now part (N.) of the Palazzo Vecchio looking on to Via Gondi. Considerably to the right of the central façade springs the square tower in the same style, until at two-thirds of its height it imitates the upper section of the Palazzo below it, and throws out on corbels a windowed gallery surmounted by a battlemented parapet (this time a coda di Rondine, or swallow-tailed). This supports four stout piers, forming with their four arches a bell turret, itself capped with a diminished parapet of the same character, and pointed off with the pole bearing the Florentine standard.

Inserted, probably at the same time, and with the same meaning, is the inscription on the parapet of the tower: —

Jesus

Christus Rex Gloriæ venit in pace,

Deus Homo factus est

Et Verbum cara factum est.

Christus vincit, Christus regnat,

Christus imperat,

Christus ab omni malo nos defendat.

Barbara Virgo Dei, modo memento mei.

Jesus

Christ King of Glory comes in peace,

God was made Man

And the Word was dear.

Christ conquers, Christ reigns,

Christ commands,

Christ protects us from all evil.

Barbara Virgin of God, just remember me.

This tower, which is worth ascending for the sake of the view, contains the prison of Savonarola.

Among so many monuments whose architectural forms are the ever-true, ever-living expression of public customs and passions, none is better than Palazzo Vecchio to reproduce, in its after-energy, the character of the old Guelph city. Writable type of Florentine architecture which took and preserved a cachet so personal, so distinct, between the Romanesque and ogival styles and the architecture of the Renaissance, this building answers completely to the idea which one is made of what could be the palace of the Seigniory in Florence. By its quadrangular mass, its large apparatus with bosses, its narrow door, its rare openings, and finally, by its cracks and its loopholes surmounted by a square tower once bearing the communal belfry, does not it represent in its dark and severe beauty the essentially militant life of the republic of which it was like the new capitol? Despite the internal changes Vasari made it undergo in 1540, nothing more conforms to its destiny and to the details of its history than this beautiful Florentine palace. With a distant reminiscence of Etruscan traditions, nothing recalls better the application of the Roman style combined with the imitation of the great Greek or Roman buildings, which, at the end of the Middle Age, still covered the soil of Tuscany. What makes this historic and, so to speak, entirely local character of the Palazzo Vecchio all the better, are the badges of the various republican governments, oligarchic and monarchical, which succeeded in Florence, and which we find in the arches of the machicolations used to support the entablature. The white lily of the commune, the red lily of the Ghibellines, the keys of the Guelphs, the tools of the wool carders, then the six balls of the Medici, and even the monogram of Christ that the Florentine people, weary of having had all forms of government, wished, in 1527, to solemnly elect for king.

Alphonse Dantier, L’Italie, vol. 2, pp. 21–22.

Michelozzo, Palazzo Vecchio court, 1434 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Andrea del Verrocchio, Putto with Dolphin

c. 1470 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The beautiful little solemn court of the Palazzo, made by Michelozzo in 1434, is surrounded by a colonnade, of which the pillars were richly decorated in honour of the marriage of Francesco de’ Medici with Joan of Austria in 1565. In the centre is an exquisite fountain by Verocchio, adorned with an animated laughing boy playing with a dolphin, much recalling some of the Tanagra Amorini. It was originally ordered for his villa at Careggi by Lorenzo de’ Medici.

Nothing can be gayer or more lively than the expression or action of this child, and there is no modern bronze combining such beautiful treatment with such perfection of art. A half flying, half running motion is represented, its varied action still true to the centre of gravity.

Carl Friedrich Rumohr.

Ascending the staircase on the left of the corridor, we reach on the first floor a small frescoed gallery. On the left is the Sala dei Duecento, where the Councils of War assembled. Into this room, in 1378, burst Michel Lando, the wool-comber, bare-legged, bearing the standard of Justice, at the head of the Ciompi, or “wooden-shoes, as they were called, in token of contempt,” and here his rash followers insisted on placing him at the head of the government, and proclaiming him Gonfalonier of Florence. The ceiling is by Benedetto da Maiano.

Giorgio Vasari, Sala dei Cinquecento Ceiling, 1556-58 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

A passage leads hence to the vast Sala dei Cinquecento, built c. 1495, by the desire of Savonarola, to accommodate the popular Council after the expulsion of Piero de’ Medici. The architect of this hall was Simone di Tommaso del Pollajuolo, nicknamed Il Cronaca. It is 170 feet long by 77 broad. Cartoons for frescoes for the walls were prepared by Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, but were destroyed upon the return of the Medici in 1512. The existing frescoes are by Vasari and his pupils, and commemorate the exploits of Cosimo I. In one of them (the first on the left) he is seen leading the attack upon Siena, attended by his favourite dwarf, Tommaso Tafredi, in armour. Beneath the central arch is a statue of Leo X., and on either side Giovanni de’ Medici delle Bande Nere, father of Cosimo I., and Duke Alessandro, by Bandinelli. In it Savonarola preached before the Signoria, August 20, 1496; and both Leonardo and Michelangelo worked on its walls, depicting battle-scenes now only known by imperfect sketches in scattered collections. The custodian will also show the Quartiere di Leone Decimo, a suite of chambers called in turn Camera di Cosimo il Vecchio, Camera di Lorenzo il Magnifico, Sala di Leone X., Camera di Giovanni delle Bande Nere, with his portrait, Salotto di Clemente VII., Scenes of the Siege of Florence, Camera di Cosimo I. Here Victor Emmanuel opened his first parliament. Another suite of chambers on this floor, called “The Medici Rooms,” because adorned with frescoes, by Vasari, illustrating the history of that family, are approached by a different staircase.

The second flight of stairs leads (left) first to the Sala del Orologio, so called from the orrery which it once contained, to show the movements of the planets, the work, in 1500, of Lorenzo di Volpaia. It has a splendid ceiling. The left wall is covered by a grand but injured fresco painted by D. Ghirlandajo in 1482. It represents S. Zenobio throned in state, with mitre and pastoral staff. In the architectural compartments at the sides are Brutus, Scaevola, and Camillus, Decius Mus, Scipio, and Cicero.

Hence, by a beautiful marble doorway, the work of Benedetto da Majano, we enter the Sala dell’ Udienza, surrounded by frescoes from Roman history by Francesco de’ Rossi Salviati. Formerly a statue of Justitia stood over the entrance.

The six Priors of the Arts, composing the Council of the Signory, who were first created in 1282, exercised their duties in the Sala dell’ Udienza. Their term of office was two months, and none could be re-elected within two years. They were maintained at the public cost, eating at one table, and during their two months of office were rarely allowed to quit the walls of the Palazzo. All their acts were conducted with religious solemnity; the wine brought to their table was consecrated on the sacred altar of Or San Michele, and in the small chapel of S. Bernard, leading out of this chamber, the Priors invoked Divine aid before commencing business.

Susan and Joanne Horner, Walks in Florence, vol. 1, p. 278.

A door, with columns of Breccia Corallina, and inscribed “Sol Justitiæ Christus Deus noster regnat in aeternum” [The Sun of Righteousness, Christ our God reigns forever] leads into the Chapel of S. Bernardo or Cappella dei Priori. It is beautifully painted in imitation of mosaic by Ridolfo Ghirlandajo. The ceiling has a gold ground. In the centre is the Trinity; the other compartments are occupied by nobly solemn apostles and exquisitely beautiful cherubs: opposite the altar is the Annunciation, in which the Piazza dell’ Annunziata is introduced. The ivory crucifix is the work of Gio. da Bologna. Here Savonarola received the sacrament before his execution.

The three friars passed the whole night in prayer, and in the morning they again met, to receive the Sacrament. Leave had been given to Savonarola to administer it with his own hands; and, holding up the host, he pronounced over it the following prayer: “Lord, I know that Thou art that perfect Trinity, invisible, distinct, in Father, Son, and Holy Ghost; I know that Thou art the Eternal Word; that Thou didst descend into the bosom of Mary; that Thou didst ascend upon the cross to shed blood for our sins. I pray Thee that by that blood I may have remission of my sins, for which I implore Thy forgiveness; for every other offence and injury done to this city, and for every other sin of which I may unconsciously have been guilty.” After this full and distinct declaration of faith, he himself took the communion, gave it to his disciples, and soon after it was announced to them that they must go down to the piazza.

Pasquale Villari, History of Savonarola, vol. 2, pp. 356–57.

Hence is the entrance to four rooms originally pertaining to the Republican Priori, but which were given by Cosimo I. to his wife Eleanora of Toledo, whose son Francesco was born here in 1541. The ceilings are painted with the lives of good women by Jean Stradan of Bruges. The wall paintings are by Vasari. In the last of these rooms a cruel and mysterious murder was committed in 1441.

A Florentine named Baldassare Orlandini, while commissary for the army during a war with the Milanese, basely abandoned a pass in the Apennines, allowing Niccolò Piccinino, the hostile general to penetrate the valley of the Arno. His conduct was boldly denounced by Baldaccio de’ Anghiari, a faithful soldier of the Republic, who led the Florentine infantry. Some years later, in 1441, when the chronicler Francesco Giovanni, who tells the story, was Prior, Orlandini, who had been chosen Gonfalonier, with apparent friendliness, sent for D’Anghiari to the palace. Suspecting treachery, he hesitated to obey, and sought advice from Cosimo Vecchio, who, fearing that the virtue and ability of D’Anghiari might be prejudicial to Medicean interest, cunningly replied, that obedience was the first duty in a citizen. Baldaccio accordingly repaired to the palace, where Orlandini received him with courtesy, and was leading him by the hand to his own chamber, when ruffians, hired by the Gonfalonier for the purpose, and placed in concealment, rushed on their intended victim, and, after despatching him with their daggers, threw his body into the cortile below. His head was cut off and his mangled remains exposed on the piazza, where he was proclaimed a traitor to the Republic. A part of his confiscated property was, however, restored on the prayers of his widow Annalena, who, after the death of her infant son, retired from the world, and converted her dwelling in the Via Romana into a convent which bore her name.

Susan & Joanna Horner, Walks in Florence, vol. 1, pp. 281–82.

It was in these rooms that the Duchess stormed at Benvenuto Cellini when he passed through to speak with the Duke—as he tells us in his autobiography. Benvenuto had an awkward knack of suddenly appearing here whenever the Duke and Duchess were particularly busy; but their children were hugely delighted at seeing him, and little Don Garcia especially used to pull him by the cloak “and have the most pleasant sport with me.”

Edmund Gardner, The Story of Florence, p. 154.

Opening from this chamber is a small Chapel intended for the use of the Grand Duchess, adorned with admirable frescoes illustrating the story of Moses, by Bronzino.

In the Quartiere di Leone Decimo (only shown—because used as offices by the Sindaco and Council—between 9 and 10 A.M.) we may visit the Camera di Cosimo il Vecchio, whose life is represented in its frescoes; the Camera di Lorenzo il Magnifico; the Sala di Leone X., with interesting frescoes of his story, and busts by Alphonso Lombardi; the Camera di Giovanni delle Bande Nere, with his portrait and that of his wife Maria Salviati; the Salotto di Clemente VII., and the Camera di Cosimo I., where the historic frescoes are mostly by Vasari.

In the tower is the chamber called Alberghettino, where, in 1433, Cosimo de’ Medici was imprisoned by Rinaldo degli Albizzi before his exile, and where Macchiavelli narrates that the future “Father of his country” refused all nourishment except a piece of bread, through four days, from fear of poison. In it, also, Savonarola wrote his renowned “Meditations.”

Beyond the second court, stairs lead to the Sala del Matrimonio (hung with tapestries depicting the story of Esther), where civil marriages are performed.

Let us leave the Piazza della Signoria by the Via dei Magazzini near the Palazzo della Mercanzia. We cross the Via Condotta, where, turned into different shops, stands a portion of the famous Palazzo dei Cerchi,11 at one time the temporary residence of the Priors, before they moved (1299) to the Palazzo Vecchio. For a hundred years it was the palace of the Bandini. Here, in the time of Bernardo Bandini, the Pazzi conspired for the assassination of Lorenzo and Giuliano de’ Medici; and hence, from the tower-top, in 1530, Giovanni Bandini, by his signals, betrayed Florence to the Imperialists, who were besieging the city. Umiliana dei Cerchi, who lived as a recluse in one of the towers of her family, was canonised after her death.

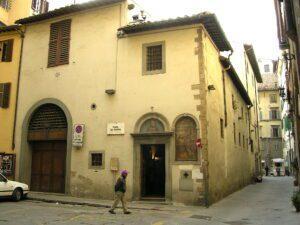

Church of S. Martino, c. 1400 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Via dei Magazzini soon reaching Via Dante, ends at (left) the humble, yellow-washed Church of S. Martino, with a fresco at the angle, founded 786 by the Irish S. Andrew, Archdeacon of Fiesole. It is interesting from association with the Society called the “Buonuomini di San Martino,” formed by S. Antonino (1389–1459) for the private relief of persons of the upper class reduced to poverty by misfortune— “I Poveri Vergognosi,” [the ashamed poor] as they were called. The church contains twelve lunettes with paintings relating to the works of mercy, sometimes attributed to Filippino Lippi. The old man with white hair in the central compartment is said to be a portrait of Piero Capponi. The tabernacle at the corner is by Cosimo Ulivelli.

Opposite the church is the tall Romanesque tower called Bella Castagna [Beautiful Chestnut], once the residence of the Podestàs, or foreign governors of Florence, before they removed to the Bargello in 1261.

It looks down upon a much modernised house in the Via S. Martino, called La Casa di Dante, where an inscription tells that Dante was born in 1265. His parents belonged to the Guild of Wool. In the neighbouring church he was married to Gemma, daughter of Manetti Donati, whose house was close to that of the Alighieri, in the present Piazza dei Donati. Wherever we turn there is delightful irregularity, rustic basements, polygonal pavement, green shutters, and the swifts are whirling and screaming about the projecting eaves overhead.

The birthplace of Dante, 211 years later, became a wine-shop of the artist Mariotto Albertinelli, to which Michelangelo, Benvenuto Cellini, and other famous men of the day were wont to resort. The house (open Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays from 11 to 3), was of great interest as late as 1877, but has since been completely “renovated,” to the minishment of its value, scarcely a stone of the house which Dante looked upon having been spared. Dante had seven children by Gemma, who was sister of that Corso Donati who, at the head of the Neri, overran Florence with fire and sword (Nov. 5, 1301). She never saw him again after his exile, but, when his house was on fire, she saved his manuscripts, and restored them to him in safety.

The Via Margherita (up which we get a significant glimpse of the Red Cupola of the Duomo with its white ribs), leads from the Piazza S. Martino into the Via del Corso, where, on the opposite side, is the Church of S. Margherita dei Ricci. It was erected to protect a fresco of the Annunciation by Taddeo Gaddi (formerly in the piazzetta of S. Maria degli Alberighi), because the youth Antonio Rinaldeschi, enraged at his gambling losses, threw dirt at the picture in his passion, and was punished (1508) by a sudden death, like Heine’s young friend, from too tight a cravat lent him by a certain Government official. The fresco is called the Madonna dei Ricci, from the family for whom it was painted by Taddeo Gaddi. The porch is by G. Salvini. Near the church stands the old Tower of the Donati at Via del Corso, 31.

A little behind is the Piazza S. Elisabetta, where the church of S. Michele delle Trombe commemorated the trumpeters of the Republic, who preceded the Priori on great occasions, and had a residence close by. A tower on the south of the square is called La Pagliazza, it is said, from the straw beds of its inmates when it was used as a prison. Today the tower, which dates perhaps to the 6th century and claims to be among the oldest structures in Florence, provides the entrance to more upscale lodgings at the luxurious Hotel Brunelleschi.

Bartolomeo Ammannati, Palazzo Salviati, c. 1565–70 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

At the corner, where the Corso falls into the Via del Proconsolo, is the Palazzo Salviati [now Palazzo Portinari Salviati],13Arms of Salviati: Gules 3, Bendlets double-crenelly, argent; crest, an eagle holding a ring in its beak. After a six-year renovation, the Palazzo Portinari Salviati reopened to the public in April 2022. occupying the site of the house of Folco Portinari, father of the Beatrice of Dante. In its court is shown the “Nicchia di Dante,” [Dante’s niche] where the poet is supposed to have watched for his love. On May-Day, 1274, the little poet, then not nine years old, was brought by his father, Alighiero Alighieri, to a fête given by Folco Portinari, and then, for the first time, he saw and loved the eight-year-old Beatrice, who, in her twentieth year, married Simone de’ Bardi, and died (1290) four years after.

It was the custom in our city for both men and women, when the pleasant time of spring came round, to form social gatherings in their own quarters of the city for the purpose of merry-making. In this way Folco Portinari, a citizen of mark, had, amongst others, collected his neighbours at his house upon the 1st of May, for pastime and rejoicing; among these was the aforenamed Alighieri, and with him—it being common for little children to accompany their parents, especially at merry-makings—came one Dante, then scarce nine years old, who, with the other children of his own age that were in the house, engaged in the sports appropriate to their years. Among these others was a little daughter of the aforesaid Folco, called Bice, about eight years old, very winning, graceful, and attractive in her ways, in aspect beautiful, and with an earnestness and gravity in her speech beyond her years. This child turned her gaze from time to time upon Dante with so much tenderness as filled the boy brimful with delight, and he took her image so deeply into his mind, that no subsequent pleasure could ever afterwards extinguish or expel it. Not to dwell more upon these passages of childhood, suffice it to say, that this love—not only continuing, but increasing day by day, having no other or greater desire or consolation than to look upon her—became to him, in his more advanced age, the frequent and woeful cause of the most burning sighs, and of many bitter tears, as he has shown in a portion of his Vita Nuova.

Boccaccio, quoted in Dante Vita Nuova, Trans. Theo. Martin, pp. xii-xiii.

Nine times already, since my birth, had the heaven of light returned to well-nigh the same point in its orbit when to my eyes was first revealed the glorious lady of my soul, even she who was called Beatrice by many who wist not wherefore she was so called. She was then of such an age, that during her life the starry heavens had advanced towards the East the twelfth part of a degree, so that she appeared to me about the beginning of her, and I beheld her about the close of my ninth year. Her apparel was of a most noble colour, a subdued and becoming crimson, and she wore a cincture and ornaments befitting her childish years. At that moment (I speak it in all truth) the spirit of life which abides in the most secret chambers of the heart began to tremble with a violence that showed horribly in the minutest pulsations of my frame; and tremulously it spoke these words:—“Ecce deus fortior me, qui veniens dominabitur mihi!”—“Behold a god stronger than I, who cometh to lord it over me!” and straightway the animal spirit which abides in the upper chamber, whither all the spirits of the senses carry their perceptions, began to marvel greatly, and addressing itself especially to the spirits of vision, it spoke those words:—“Apparuit jam beatitudo vestra”—“Now hath your bliss appeared,” and straightway the natural spirit, which abides in that part whereto our nourishment is ministered, began to wail, and dolorously it spoke these words: —“Heu miser! quia frequenter impeditus ero deinceps!”—“Ah, wretched me, for henceforth shall I be oftentimes obstructed!” From that time forth I say that Love held sovereign empire over my soul, which had so readily been betrothed unto him, and through the influence lent to him by my imagination he at once assumed such imperious sway and masterdom over me, that I could not choose but do his pleasure in all things. Oftentimes he enjoined me to strive, if so I might behold this youngest of the angels; wherefore did I during my boyish years frequently go in quest of her, and so praiseworthy was she, and so noble in her bearing, that of her might with truth be spoken that saying of the poet Homer—“She of a god seemed born, and not of mortal man.” And albeit her image, which was evermore present with me, might be Love’s mere imperiousness to keep me in his thrall, yet was its influence of such noble sort that at no time did it suffer me to be ruled by Love, save with the faithful sanction of reason in all those matters wherein it is of importance to listen to her counsel.

Dante, Vita Nuova, Trans. Theo. Martin, pp. 1–3.

Folco Portinari died December 31, 1289. In his will (of January 15, 1287) he leaves a legacy of fifty pounds to his daughter Beatrice, wife of Simone de’ Bardi. He was buried with a public funeral at the Hospital of S. Maria Nuova, which he had founded (q.v.).

Maria Salviati, a daughter of this palace, married Giovanni delle Bande Nere, and became the mother of Cosimo I., whose statue in the court was placed here in 1631.

Bernardo Buontalenti, Palazzo Nonfinito, 1593–1604 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Borgo degli Albizzi (continuing the Via del Corso and crossing the Via del Proconsolo) derives its name from the famous old family which dwelt here. In one corner is the Palazzo Nonfinito (Via del Proconsolo, 12),14Now Museo di Antropologia. founded by Alessandro Strozzi, 1592, from the design, never completed, of Bernardo Buontalenti. The part which exists is exceedingly stately, and was occupied by the Central Telegraph office.

Palazzo Quaratesi Courtyard (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Opposite is the Palazzo Quaratesi, which belonged to the Pazzi. The design, with a rustic rez-de-chaussée [ground floor], was originally made by Brunelleschi for Andrea Pazzi, but was carried out after his day by his son Jacopo. The courtyard is admirable. The escutcheon in the corner is by Donatello: bearing azure, two dolphins, addorsed, or; between four crosses crosslet, fitchée, or. A beautiful fanale, or cresset, projects over the street. The “Cantonata dei Pazzi” is still the scene of a ceremony observed from the time of the Crusades.

Popular tradition narrates that in 1099 a Florentine of the name of Raniero led 2500 Tuscans to support Godfrey of Bouillon in his attempt to recover the Holy Land. Raniero planted the first Christian standard on the walls of Jerusalem; and in requital Godfrey permitted him to carry back to Florence a light kindled at the sacred fire on the Saviour’s tomb. Raniero started on horseback to return home, but finding that the wind, as he rode, would soon extinguish the light, he changed his position, and sitting with his face to the horse’s tail, conveyed the sacred relic safely to Florence. As he passed along, all who met him called out that he was pazzo, or “mad,” and thence arose the family name of the Pazzi. The light was placed in San Biagio; and ever since, on Saturday in Passion Week, a coal which is kindled there is borne on the Carroccio to the Cantonata dei Pazzi before it is taken to the cathedral; and, in both places, an artificial dove, symbolical of the Holy Spirit, by some mechanical contrivance is made to light a lamp before the sacred image at this corner, and on the high-altar of the cathedral.

Susan & Joanna Horner, Walks in Florence, vol. 1, pp. 299–300.

Another Pazzi Palace was No. 29, and its cortile has fine octagonal columns.

On the opposite side of the street, at the corner of the Borgo degli Albizzi,15Arms of Albizzi: Sable,2 annulets concentric, or. is (No. 24) the Palazzo Montalvo, restored in the reign of Cosimo I. by Ammanati. In the court is a bronze Mercury by Giovanni da Bologna. The ancient Palace of the Pazzi was demolished to build the National Bank.

On the other side of the street is the Palazzo dei Galli, which has a suite of rooms painted by Giovanni di San Giovanni. A little farther is the Casa Londi, which bears an inscription, saying that Galuzzi, the historian of the Medici, died there.

Immediately beyond is (No. 15) the interesting old frescoed Palazzo Alessandri, founded by Alessandro Albizzi,16Arms of Alessandro: Az. a lamb, with 2 heads, addorsed, passant, argent, in allusion to the Guild of Wool. who, quarrelling with his brother, dropped the family name. Twenty-three priors and nine gonfaloniers sprang from the Alessandri branch, but amid their honours they never despised the trade from which they derived their wealth and power, and the iron cramps may still be seen upon which the cloth they continued to manufacture was spread out to dry in the sun on the roof of their palace. Some rooms, with old windows under pointed arches, are hung with cloth of gold and velvet from the palios won by the Alessandri at the horse-races in the Corso: some of the gold hangings are most magnificent. Canova resided here while in Florence. The palace contains a few good pictures by Botticelli (copy), Pesellino, Fil. Lippi, and Jacopo da Empoli, and some small sculptures by Donatello and Mino da Fiesole. The original inhabitants of all these palaces may be studied in their quaint costumes in the frescoes of the Carmine.

San Pier Maggiore Loggia (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Lower down the street is an arch crossing one side of a piazzetta, being all that remains of the Church of S. Pietro Maggiore, where (Aug. 1525) Giovanni della Robbia was buried by the side of his uncle Luca (ob. Feb. 20, 1482), and where the Puccini family had their burial-place before the XVI. c. The Casa Casuccini stands on the site of one of the towers where Corso Donati defended himself against the people in the fourteenth century.

The Palazzo Valori (No. 18), called Palazzo dei Visacci from the busts of ugly people which adorn it, marks the site of the palace of Rinaldo degli Albizzi, who died in exile at Ancona in 1452 for his opposition to the Medici. The existing palace was built by Ammanati for Baccio Valori, whose bust is over the entrance. He himself was hanged at the Bargello c. 1535

Before leaving the Via degli Albizzi we must remember that this was the scene of the miracle of S. Zanobio.