The ambitious, but far from finished, Pitti Palace, stands upon a basement of huge blocks of stone and is exceedingly imposing from the dignity of its vast lines and gigantic proportions. This rustic work is mostly an addition to the original plan.1The palace, in its original state, is shown in the background of the portrait of a lady of the Pitti family, which hangs in the corridor between the Uffizi and Pitti.

I doubt if there is a palace in Europe more monumental than the Pitti Palace. I have not seen one that leaves such a simple, grandiose impression.

Hippolyte Taine, Italy: Florence, p. 151.

Giusto Utens, Palazzo Pitti and Boboli Gardens, 1599. The 7 bay palace reflects Brunelleschi’s original design.

The palace was begun in 1441, from a design attributed to Brunelleschi, by Luca Pitti, a vain old millionaire Florentine, and was sold by his descendants, in 1549, to Eleanora of Toledo, wife of Cosimo I. Long the residence of the Medici Grand-Dukes and, after the end of the line with the death of Gian Gastone in 1737, by members of the House of Lorraine, followed by the Kings of Italy. Here, on October 9, 1870, Victor Emmanuel II. received the Roman deputations who came to present to him the result of the plebiscite by which the Romans had voted their union with the rest of Italy under the House of Savoy. The following year, he departed to Rome, the capital of the new Italy. In 1919 Vittorio Emanuele III gave the palace and its contents to the Italian nation.

The façade of the Pitti is 475 [sic. Should read 490] feet in extent, three stories high in the centre, each story 40 feet in height, and the immense windows of each 24 feet apart from centre to centre. With such dimensions as these, even a brick building would be grand; but when we add to this, the boldest rustication all over the façade, and cornices of simple but bold outline, there is no palace in Europe to compare to it for grandeur, though many may surpass it in elegance. The design is said to have been by Brunelleschi, but it is doubtful how far this is the case, or, at all events, how much may be due to Michelozzi, who certainly assisted in its erection, or to Ammanati, who continued the building, left incomplete at Brunelleschi’s death, in 1444.

James Fergusson, History of the Modern Styles of Architecture, p. 85.

Brother heart to the mountain from which it is rent.

John Ruskin.

The two long wings and cortile of the palace were additions by Bartolommeo Ammanati (1568). At the left corner of the main building, near the entrance to the gardens, is the approach to the pictures.2Sticks or umbrellas left at the entrance of the Pitti are conveyed to the exit of the Uffizi for a fee of 25 c., for which a receipt is given. [No longer so.] The Pitti Palace may also be reached from the Uffizi by the covered gallery.3The Vassari Corridor is currently undergoing restoration and will reopen in the near future.

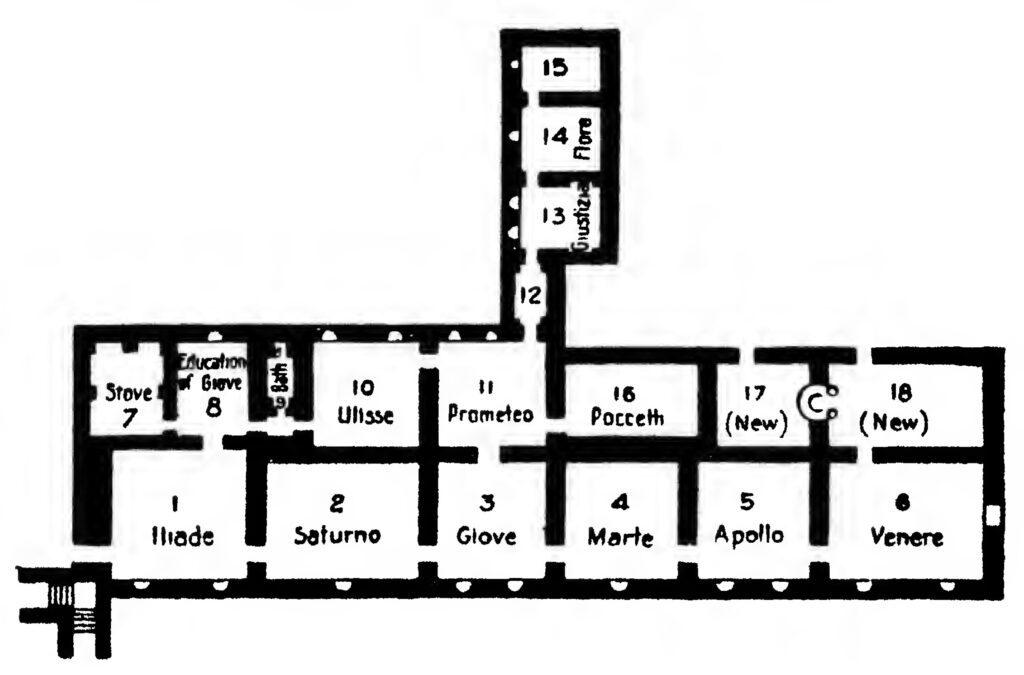

Currently the Pitti Palace is home to five museums: Treasury of the Grand Dukes and the Museum of Russian Icons (ground floor); Palatine Galleries and Royal Apartments (first floor); and The Modern Art Gallery and Museum of Costume and Fashion (second floor). If time is short, proceed directly upstairs to the piano nobile and the Palatine Galleries.

The six Palatine Gallery reception rooms, overlooking the piazza in front of the palace, display the collection of paintings formed by the Medici and brought to this palace about 1641. The rooms in which the pictures are contained are most gorgeously, but harmoniously, decorated. The first room is named after Homer’s Iliad and the remaining five after classical deities.

Pietro di Cortona, Fedi and Marini, the last of the painters of the decadence, cover the ceilings with allegories in honor of this reigning family. Here is Minerva rescuing Cosmo I. from Venus and presenting him to Hercules, the type of great works and heroic exploits; he in fact, put to death or proscribed the leading citizens of Florence, and he it is who said of a refractory city that he “would rather depopulate it than lose it.” Elsewhere, Glory and Virtue are leading him to Apollo, the patron of arts and letters; he, in fact, furnished magnificent apartments and pensioned the writers of sonnets. Farther on, Jupiter and the entire Olympian group are all astir to receive him; he, in fact, poisoned his daughter, caused his daughter’s lover to be killed and slew his son who had slain a brother; the second daughter was stabbed by her husband, and the mother died on account of it; these operations re- commence in the following generation: assassinations and poisonings are hereditary in this family.

Hippolyte Taine, Italy: Florence, p. 153.

Beginning in the Sala d’Iliade (27) are the gems of the collection (which include ten works of Raffaelle).

Raffaello Sanzio (1483–1520), La Gravida, 1505–06. Attributed to Ridolfo Ghirlandajo by G.B. Cavalcaselle, but now universally given to Raphael. Much injured by retouching.

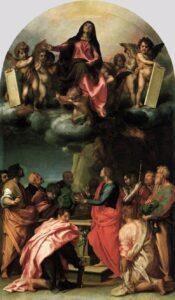

Fra Bartolomeo, Holy Conversation (also called The Mystic Marriage of St Catherine or the Pitti Panel)—inscribed “1512, orate pro pictore.” […for the painter] Although injured, one of the grandest creations of the master, perfect in composition, drawing, and relief; especially noble is the figure of S. Michael in armour. The picture is ill-seen here, being painted for an especial position and light in a church.

Sala di Saturno (28):

Raffaelle. La Madonna del Gran-Duca, c. 1505—a panel-picture which belonged to Carlo Dolce, and was sold to Ferdinand III. for 3360 lire.

We may notice here especially the heavy eyelid which is characteristic of the Madonnas of Raffaelle—the “santo, onesto e grave ciglio” [holy, honest and grave eyelid] which Giovanni Sanzie attributes to Battista Sforza, and which is exaggerated in the works of Francia and Perugino. The arch over the eyes of the Madonnas of Raffaelle is generally almost invisible; Castiglione, in his Cortegiano, mentions that Italian ladies were in the habit of removing the hairs of their eyebrows and foreheads.

Here the Madonna holds the Infant tranquilly in her arms, and looks down in deep thought. Although slightly and very simply painted, especially in the nude, this picture excels all Raffaelle’s previous Madonnas in that wonderful charm which only the realisation of a profound thought could produce. We feel that no earlier painter had ever understood to combine such free and transcendent beauty with an expression of such deep foreboding. This picture is the last and highest condition of which Perugino’s type was capable.

Franz Theodor Kugler, Handbook of Painting, vol. 2, p. 415.

The Madonna Gran-Duca marks the growing transition from the first to the second manner of Raffaelle. The Virgin has all the pensive sweetness and reflective sentiment of the Umbrian school, while the Child is loveliness itself. We think of Perugino still, but we think of him as suddenly endued with a purer, firmer outline, and more refined sentiment.

J. S. Harford, Life of Michael Angelo, vol. 1, p. 323.

When Raphael was asked where he found the model of his virgins, he replied, like a Platonist—that it was in reality:—“in a certain idea.”

Emile Montégut, Poètes et artistes de l’Italie, p. 288.

Raffaelle, La Madonna della Sedia, c. 1513–14—a “tondo.”

A pretty legend tells that, in the hills which girdle the Roman Campagna, lived the old hermit Fra Bernardo. In a great storm his life was saved by the self-devotion of Maria, daughter of a neighbouring vine-dresser, and by the branches of an oak in which he had taken refuge. In his gratitude he prayed that God would distinguish them. Years passed, the hermit died, and the oak tree was made into casks by the father of Maria. One day she sat on one of the casks playing with her children, and just as one of them ran up to her with a stick in the form of a cross, Raffaelle passed by, and drew the beautiful mother and children on the smooth end of the wine cask, which he took away with him, and in the Madonna della Seggiola the hermit’s prayer was fulfilled.4See Mrs. Clements’ Christian Symbols and Stories of the Saints.

This picture proclaims him a colourist.

Crowe and Cavalcaselle, Raphael: His Life and Works, vol. 2, p. 230.

A circular picture, painted about 1516. The Madonna, seen in a side view, sits on a low chair holding the Child on her knee; he leans on her bosom in a listless, child-like attitude; at her side S. John folds his little hands in prayer. The Madonna wears a many-coloured handkerchief on her shoulders, and another on her head, in a manner of the Italian women. She appears as a beautiful and blooming woman, looking out of the picture in the tranquil enjoyment of maternal love: the Child, full and strong in form, has a serious, ingenuous, and grand expression. The colouring is uncommonly warm and beautiful.

Franz Theodor Kugler, Handbook of Painting, vol. 2, p. 453.

It is the expression of a peasant rather than of the mother of God. In other respects it is a fine figure, gay, agreeable, and very expressive of maternal tenderness.

Tobias Smollett, Letter XXVIII.

There is nothing else approaching the sweetness of the head of the Virgin, the majesty of the infant Jesus, and the unction and ardent devotion of St. John. Every thing about these two children is prophetic. The one revolves in his thought the destinies of the world: the other is already consecrating his to its service.

Count de Falloux, Life and Letters of Madame Swetchine, p. 213.

The Madonna della Sedia leaves me, with all its beauty, impressed only by the grave gaze of the Infant.

George Eliot, George Eliot’s Life as Related in Her Letters and Journals, vol. 2, p. 223.

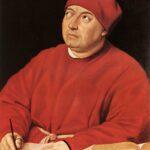

Raffaelle, Julius II, 1511-12. This painting was moved to the Uffizi after the end of WWII and returned to the Pitti Palace in the 21st century. It is well to contrast this Pope’s portrait with that of Leo X. A copy by Titian is in the Sala di Venere.

The high-minded old man is here represented seated in an arm-chair in deep meditation. The small, piercing, eyes are deeply set under the open, projecting forehead; they are quiet, but of extinguished power. The nose is proud and Roman, the lips firmly compressed; all the features are still in lively, elastic tension; the execution of the whole picture is masterly. There are several repetitions; one is in the gallery of the Uffizi, representing the Pope in a red dress. A good copy is also in the Berlin Museum; another at Mr. Miles’s of Leigh Court.

Franz Theodor Kugler, Handbook of Painting, vol. 2, p. 389.

Seated in an arm-chair, with head bent downwards, the Pope is in deep thought. His furrowed brow and his deep-sunk eyes tell of energy and decision. The down-drawn corners of his mouth betoken constant dealings with the world. Raffaelle has caught the momentary repose of a restless and passionate spirit, and has shown all the grace and beauty which are to be found in the sense of force repressed and power at rest. He sets before us Julius II. as a man resting from his labours, and brings out all the dignity of the rude, rugged features. The Pope is in repose; but repose to him was not idleness—it was deep meditation. A man who has done much and suffered much, he finds comfort in his retrospect and prepares for future conflicts.

Mandell Creighton, A History of the Papacy, vol. 4, pp. 175–76.

Raffaelle, Leo X., with his Nephews, Cardinals Giulio de’ Medici and Luigi de’ Rossi, c. 1518-20—a grand portrait. Giulio subsequently became Pope Clement VII (1523-34).

Scholars have identified the illuminated codex as a Bible, now in Berlin, created in Naples in the mid-14th century. The codex is open to the first page of the Gospel according to John, the initial verse of which reads: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (KJV)

The portrait was moved to the Uffizi in the 1950s, but has now been returned to the Pitti Palace.

In the portrait may be seen the Pope’s eyeglass, the “specillum” through which, according to Pellicanus, he used to watch processions, the “cristallum concavum,” which, according to Giovio, he used when hunting. His bad sight was proverbial. After his election, the Roman wits explained the number MCCCCXL., engraved in the Vatican, as follows ”Multi caeci cardinales creaverunt caecum decimum Leonem. [Many blind cardinals created the blind Leo X.]

Jacob Burckhardt. The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, vol. 1, p. 158 (note 1, edited somewhat by Hare).

Raffaelle(?), Cardinal Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena, c. 1516, tutor to the sons of Lorenzo “Il Magnifico,” d. 1520. A native of Bibbiena, in the Casentino, Bernardo Dovizi was tutor to the sons of Lorenzo de’ Medici. One of his pupils, afterwards Pope Leo X., made him a Cardinal. He is supposed to have died of poison. Morelli considers this portrait to be only the work of a scholar of Raffaelle.

It is quite ruined by rehandling and patching, whatever it may or may not have been originally.

Bernardo Dovizi had been chosen by Lorenzo de’ Medici to be his son’s tutor in early days. He showed himself faithful to the trust confided to him, and his tact and skill were of great value in securing Giovanni’s election to the Papacy. . . . His reputation as a courtier is largely due to his comedy La Calandra, in which a brother and sister disguise their sexes, a framework for scenes in which considerations of decency have little place. Bibbiena’s private life was according to the morality of his play. His house was shared by a concubine, who bore him three children. Leo, who witnessed the performance of La Calandra in the Vatican, was not shocked by this breach of ecclesiastical vows, but satisfied his sense of decorum by not creating Bibbiena a Cardinal till after his concubine’s death.

Mandell Creighton, History of the Papacy, vol. 6, pp. 198–99.

Raffaelle, La Madonna del Baldacchino—ordered for the chapel of the Dei in S. Spirito, painted 1508, but left unfinished when Raffaelle was summoned to Rome by Julius II., and much repainted and spoilt.

The Madonna and Child are on a throne; on one side stand S. Peter and S. Bruno; on the other, S. Anthony and S. Augustine; at the foot of the throne two boy-angels hold a strip of parchment with musical notes inscribed on it; over the throne is a canopy (baldacchino), the curtains of which are held by two flying angels. The picture is not deficient in the solemn majesty suited to a church subject; the drapery of the saints, particularly that of S. Bruno, is very grand; in other respects, however, the taste of the naturalisti prevails, and the heads are in general devoid of nobleness and real dignity. In the colour of the flesh this picture forcibly reminds us of Fra Bartolommeo. Raffaelle left it unfinished in Florence; and in this form, with an appearance of finish which is attributable to restorations, it has descended to us.

Franz Theodor Kugler, Handbook of Painting, vol. 2, p. 422.

This picture remains a puzzle. Raffaelle left it unfinished on his journey to Rome; later, when his growing fame called fresh attention to the picture, the painting was continued we know not by whom. At last Ferdinand, son of Cosimo III., had it touched by a certain Cassana, with an appearance of finishing chiefly by means of brown glazings. The remarkably beautiful attitude of the Child with the Madonna (for instance, that of the hands), the figures on the left, arranged in the grand style of the Frate (S. Peter and S. Bernard), belong surely to Raffaelle; perhaps also the upper part of the body of the saint on the right, with the pilgrim’s staff; on the other hand, the bishop on the right might be composed by quite another hand. The two beautifully improvised Putti on the steps of the throne belong as much to the style of the Frate as of Raffaelle; of the two angels above, the more beautiful one is obviously borrowed from the fresco of S. Maria della Pace at Rome, from which it appears that the first finisher did not touch the picture till after 1514.

Jacob Burckhardt, Cicerone, p. 134–35.

-

Raffaelle. (?) Portrait of Tommaso Inghirami. Morelli considers this fine portrait to be only a copy, by a foreign master, from the original Raffaelle, which is still in the possession of the Inghirami family at Volterra, though ruined by restorations.

Tommaso Phaedra Inghirami was of a noble family of Volterra. Having lost his father at two years old, he was taken at once under the protection of the Medici, who provided for his education. His name of Phaedra was the result of an extraordinary proof of wit and presence of mind. While acting in the tragedy of “Hippolytus” at the house of the Cardinal of S. Giorgio, in which he filled the part of Phaedra, something which went wrong with the machinery interrupted the performance. Inghirami immediately stepped forward and filled up the interval by an impromptu of Latin verses, which produced immense applause and shouts of “Viva Phaedra!” and the name afterwards stuck to him and was added to his own. He was sent as ambassador by Alexander VI. to Maximilian, who gave him the title of Count Palatine. In 1510 he was made Bishop of Ragusa by Julius II., and officiated as secretary at the conclave in which Giovanni de’ Medici was elected Pope. It is in the red dress which he then wore that he is represented by Raffaelle.

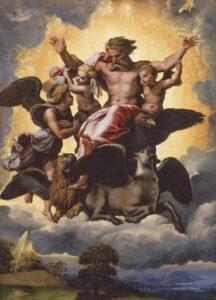

Raffaelle. The Vision of Ezekiel often attributed to Giulio Romano, painted (probably in 1517) for the Ercolani family at Perugia. Probably the master merely designed it.

It contains the First Person of the Trinity, in a glory of brightly illuminated cherubs’ heads, His outstretched arms supported by two genii, and resting on the mystical forms of the ox, eagle, and lion; the angel is introduced adoring beside them. Dignity, majesty, and sublimity are here blended with inexpressible beauty; the contrast between the figure of the Almighty and the two youthful genii is admirably portrayed, and the whole composition so clearly developed, that it is undoubtedly one of the master-works of the artist. Michelangelo, who had also given a type of the Almighty, represents Him borne upon the storm; Raffaelle represents Him as if irradiated by the splendour of the sun; here both masters are supremely great, similar, yet different, and neither greater than the other.

Franz Theodor Kugler, Handbook of Painting, vol. 2, p. 449.

Truly, it is a vision. Torrents of light dazzle the spectator. He feels as if he were seized by the arms of fire that upbear the prophet. It is not merely the coloring which astonishes you. There is in the drawing of this little picture, an energy, a boldness, and a richness which are incomparable. It is indeed Jehovah, the true God of the Old Testament, who is revealed to Raphael, —more poet than painter here. It is a strophe repeated from the divine songs.”

Count de Falloux, Life and Letters of Madame Swetchine, pp. 213–14.

Raffaelle. (?) Cardinal Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena, tutor to the sons of Lorenzo “Il Magnifico,” d. 1520.

A native of Bibbiena, in the Casentino, Bernardo Dovizi was tutor to the sons of Lorenzo de’ Medici. One of his pupils, afterwards Pope Leo X., made him a Cardinal. He is supposed to have died of poison. Morelli considers this portrait to be only the work of a scholar of Raffaelle. It is quite ruined by rehandling and patching, whatever it may or may not have been originally.

Bernardo Dovizi had been chosen by Lorenzo de’ Medici to be his son’s tutor in early days. He showed himself faithful to the trust confided to him, and his tact and skill were of great value in securing Giovanni’s election to the Papacy. . . . His reputation as a courtier is largely due to his comedy La Calandra, in which a brother and sister disguise their sexes, a framework for scenes in which considerations of decency have little place. Bibbiena’s private life was according to the morality of his play. His house was shared by a concubine, who bore him three children. Leo, who witnessed the performance of La Calandra in the Vatican, was not shocked by this breach of ecclesiastical vows, but satisfied his sense of decorum by not creating Bibbiena a Cardinal till after his concubine’s death.

Mandell Creighton, History of the Papacy, vol. 6, pp. 198–99.

Perugino. The Deposition, 1495—from the convent of S. Chiara and greatly admired for its landscape, as well as for the figures it contains.

The Maries also, having ceased to weep, are contemplating the departed Saviour with an expression of reverence and love which is singularly fine.5Alternate translation: The Marys, having stopped weeping, look on the dead with wonder and love.

Giorgio.Vasari, Lives, Blashfield trans., vol. 2, p. 320.

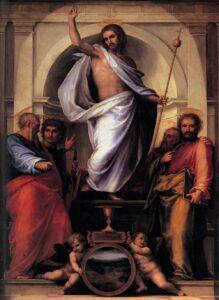

Sala di Giove (29):

Raffaelle. “La Donna Velata,” resembling a picture of S. Catherine by Raffaelle, now lost, but once in the possession of the collecting Earl of Arundel, and engraved by Hollar. This picture, which was brought in 1824 from Poggio Reale, is an undoubted work of Raffaelle. It was in the possession of the Botti family in 1677, when Cinelli saw it, and described it as an original. It bears the same type, of a beautiful Roman woman, depicted in the Madonna di S. Sisto. The Directors of this Gallery ascribed the masterpiece to an unknown hand until ten years ago.

Andrea del Sarto. S. John Baptist, c. 1523—painted for Ottaviano de’ Medici

This picture combines the composition of Michelangelo with a trace of Venetian colouring, but, besides the unpleasantness of the subject, it is unattractive to the spectator by the obvious sacrifice of all freshness of life for a style of art which, after all, Sebastian never entirely acquired.

Franz Theodor Kugler, Handbook of Painting, vol. 2, p. 437.

Sala di Marte (30):

Titian, Portrait of Cardinal Ippolito de’ Medici, 1532-33, as a Magyar noble. Legate to Charles V. Poisoned 1535, aged 25.

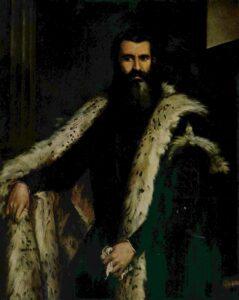

Paolo Veronese, Portrait of a Man (formerly identified as Daniele Barbaro), c. 1550-60—“Le Patricien à Venise.”

Rubens, The Four Philosophers, 1611. Himself, his brother Philip, and the philosophers Lipsius and Grotius one of the finest portrait-pictures of the master.

Sala d’ Apollo (31):

Andrea del Sarto (Andrea d’Agno 1486–1530), Virgin and Child, St. Elizabeth and the Infant St. John the Baptist (Medici Holy Family), c. 1529.

At Florence only can one trace and tell how great a painter and how various Andrea was. There only, but surely there, can the spirit and presence of the things of time on his immortal spirit be understood.

Algernon Charles Swinburne, Essays and Studies, p. 352.

That formidable young man in black, with the small compact head, the delicate nose, and the irascible blue eye. Who was he? What was he? “Ritratto virile” is all the catalogue is able to call the picture. I should think it was. Handsome, clever, defiant, passionate, dangerous, it was not his fault if he had no adventures.

Henry James, Italian Hours, p. 406.

Sala di Venere (32):

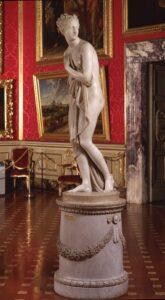

In 1802, Ludovico di Borbone, the king of Eturia, commissioned Antonio Canova to make a copy of the Venus d’Medici, which Napoleon Bonaparte had ordered moved to the Louvre. Reluctant initially to make a copy,Canova accepted the commission in 1805, but decided to create an entirely new work, one that would compete directly with, and surpass, the 1st-century original. Installed in the Uffizi’s Tribune in 1812, the sculpture was a resounding success.

After the fall of Napoleon, France returned the Medici Venus in 1815, and Canova’s masterpiece was moved to the Pitti Palace where it remains.

The beautiful “Venus”, which now decorates the [Tribune] gallery of [the Uffizi], has “truly surprised all the inhabitants of this city, who ran in crowds ” to admire it.…In this elegant statue, which was called the “Venere Italica”, the nude is large and very pure, and the head among the most beautiful of Canova’s Olympians. The goddess just emerging from the water, which seems to drip from her delicate limbs, appears even more delicate and softer. Slightly bent over and her knees bent, she presses her cloth to dry her young breast, and which, falling back into well-composed folds, covers the rest of the person, minus the right and left leg from the knee down. This act of drying seemed to the purists of classicism too common and vulgar and disdainful of the ideal nobility of a goddess…

Vittorio Malamani, Canova, Milano: U. Hoepli, 1911, pp. 166–67.

Titian, Concert of Music, 1510-11—once considered a masterpiece of Giorgione (1478–1511), whose authentic works are rare, but now regarded as an early Titian.

It is difficult sometimes to decide whether Giorgione meant to represent a real portrait, or an ideal head, or a genre subject, so well did he understand to give his figures that which especially appealed to the comprehension and sympathies of his spectators. We see this in his “Concert,” in the Pitti Palace, representing two priests playing the piano and the violoncello, with a youth.

It is difficult sometimes to decide whether Giorgione meant to represent a real portrait, or an ideal head, or a genre subject, so well did he understand to give his figures that which especially appealed to the comprehension and sympathies of his spectators. We see this in his “Concert,” in the Pitti Palace, representing two priests playing the piano and the violoncello, with a youth.

Franz Theodor Kugler, Handbook of Painting, vol. 2, p. 432.

Of the undisputed pictures by Giorgione, the grandest is the Monk at the Clavichord. The young man has his fingers on the keys: he is modulating in a mood of grave and sustained emotion; his head is turned away towards an old man standing near him. On the other side of the instrument is a boy. These two figures are but foils and adjuncts to the musician in the middle; and the whole interest of his face lies in its concentrated feeling—the very soul of music passing through his eyes.

J.A. Symonds, Renaissance in Italy: The Fine Arts, (1899), p. 269

A ripe beauty in a gold-embroidered dress, with violet-and-white padded sleeves, and a gold chain.

Franz Theodor Kugler, Handbook of Painting, vol. 2, p. 450.

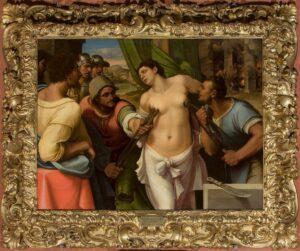

Sala dell’ Educazione di Giove (24):

Cristofano Allori (1577-1621), Judith with the Head of Holofernes, 1610-12

The most finished picture of Allori represents Judith with the head of Holofernes; she is a beautiful and splendidly attired woman, with a grand, enthusiastic expression. The countenance is wonderfully fine and Medusa-like, and conveys all that the loftiest poetry can express in the character of Judith. In the head of Holofernes it is said that the artist has represented his own portrait, and that of his proud mistress in the Judith.

Franz Theodor Kugler, Handbook of Painting, vol. 2, p. 588.

The Judith is pale with the passion and the crime of her cruel night’s work—most terrible of heroines, with such exhaustion and excitement in her face as no one but Allori, of all her painters, has ventured to put there.

“Two Cities—Two Books,” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, DCCV, p. 91.

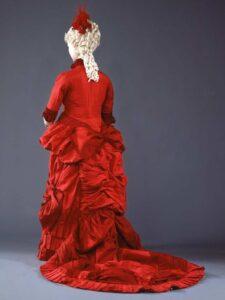

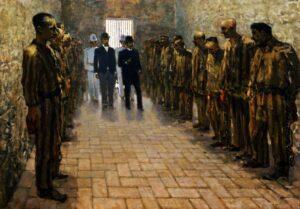

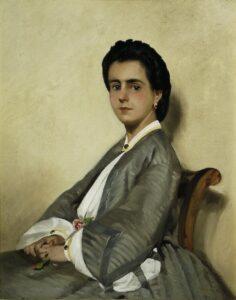

In addition to the Palatine Galleries, the Pitti Palace contains four other museums highlighting precious items in the Treasury, historic outfits in the Fashion and Costume museum, Russian icons, and Modern Art, that is 18th-20th century art. A limited sampling is seen below.

Pitti Palace seen from the Boboli Gardens (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Close to the entrance of the picture gallery is the approach to the beautiful Boboli Gardens, so called from the family whose mansion was once situated here. Near the entrance is a Grotto once containing four unfinished statues intended for the monument of Julius II. by Michelangelo, and presented by his nephew, Leonardo Buonarotti, to Cosimo I.6These four statues were moved to the Accademia in 1909. In front of the palace is an amphitheatre, whence walks, between clipped avenues of bay and ilex, lead delightfully to the higher ground, where are the Fountain of Neptune, begun by Giambologna, with a statue by Stoldo Lorenzi (1565); the statue of Dovizia—Abundance—believed to be a portrait of Joanna of Austria, first wife of Francesco I.; and the little meadow, called L’Uccellaja, from its bird-snares. The hill was called Boboli before the gardens were made.

On Sunday, I went to the highest part of the Garden of Boboli, which commands a view of most of the city, and of the vale of Arno to the westward; where, as we had been visited by several rainy days, and now at last had a very fine one, the whole prospect was in its highest beauty. The mass of buildings, especially on the other side of the river, is sufficient to fill the eye, without perplexing the mind by vastness like that of London; and its name and history, its outline and large picturesque buildings, give it grandeur of a higher order than that of mere multitudinous extent. The hills that border the valley of the Arno are also very pleasing and striking to look upon; and the view of the rich plain, glimmering away into blue distance, covered with an endless web of villages and country-houses, is one of the most delightful images of human well-being I have ever seen.

John Sterling’s “Letters.”

You see below, Florence, a smokeless city, its domes and spires occupying the vale; and beyond to the right the Apennines, whose base extends even to the walls. The green valleys of these mountains, which gently unfold themselves upon the plain, and the intervening hills covered with vineyards and olive plantations, are occupied by the villas, which are, as it were, another city—a Babylon of palaces and gardens. In the midst of the picture rolls the Arno, through woods, and bounded by the aerial snow and summits of the Lucchese Apennines. On the left a magnificent buttress of lofty, craggy hills, overgrown with wilderness, juts out in many shapes over a lovely vale, and approaches the walls of the city. Cascine and ville occupy the pinnacles and abutments of those hills, over which is seen at intervals the ethereal mountain-line, hoary with snow and intersected by clouds. The vale below is covered with cypress groves whose obeliskine forms of intense green pierce the grey shadow of the wintry hill that overhangs them. The cypresses too of the garden form a magnificent foreground of accumulated verdure; pyramids of dark leaves and shining cones rising out of the mass, beneath which are cut, like caverns, recesses which conduct into walks. The cathedral with its marble campanile, and the other domes and spires of Florence, are at our feet.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, “View from the Pitti Gardens,” The Prose Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, vol. 3, pp. 50–51.

Qui Michel-Angiol nacque? e qui il sublime

Dolce testor degli amorosi detti?

Qui il gran poeta, che in sì forti rime

Scolpi d’inferno i pianti maladetti?

Qui il celeste inventor, ch’ebbe dall’ime

Valli nostre i pianeti a noi soggetti?

E qui il sovrano pensator, ch’esprime

Sì ben del Prence i dolorosi effetti?

Qui nacque, quando non venia proscritto

Il dit, leggere, udir, scriver, pensare;

Cose, ch’or tutte appongonsi a delitto.

Was Michelangelo born here? Is here the sublime

Sweet testor of amorous sayings?

Here the great poet, in such strong rhymes

Carved evil cries from hell?

Here the celestial inventor, who from the spirit

Our valleys the planets subject to us?

And here the sovereign thinker, who expresses

Yes well of the Prence the painful effects?

Here he was born, when he is not outlawed

The dit, to read, hear, write, think;

Things, which are now all appended to crime.

Vittorio Alfieri, “Sonnet” xl, Poesie Originali, p. 130.

One of the most beautiful pictures in Florence may be obtained from the right-hand corner of the amphitheatre, whence the dome of the cathedral and the graceful tower of the Palazzo Vecchio—noblest symbol of civic liberty in the world7Alfred Austin. —are seen between a stately group of cypresses and the massy brown walls of the palace.

We have wandered up to the grassy terrace through alleys of over-arching ilex. A confused murmur from the bells of Florence throbs in the sunny air. The horse-chestnuts are in their full glory; the grass is ripe for the mower; bees are in the clover and bugle; and lovers arm-in-arm are talking beautiful things. In the distance, between us and the grey-blue mountains, stretches the gentle green ridge of Bello Sguardo, with its dark row of guardian cypresses, and white and pink villas overcanopied with Banksian roses to be. Below lies the town white with tawny roofs, cloven by the arrow-like Arno, and beyond it is the woodland Cascine. The tall tower of San Spirito stands up close to us, and the swifts are whirling around it.

St. Clair Baddeley.