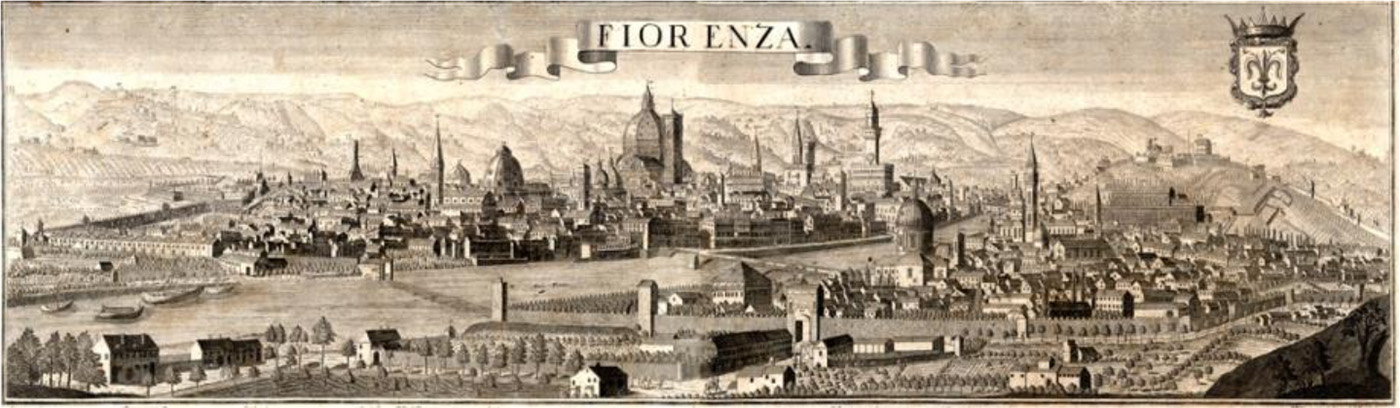

4.3: San Marco

The Via Cavour, on the other side of the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, leads (N.) to the Piazza S. Marco. Where it is crossed by the Via Guelfa is the Canto de’ Bernardetto de Medici, from the once owner of No. 31, which has been inhabited in turn by the artist Pietro Benvenuti, the engraver Giovita Garavaglia (1835), and, (1841) Prince Jerome Bonaparte. A tablet on No. 37 records the residence of the poet Giov. Batt. Niccolini. On the left (No. 45) is the Public Library (Bibliotéca Marucelliana), founded by Francesco Marucelli, who died in 1703. Beyond the library is the former Convent of S. Caterina, founded by Camilla, deserted wife of Rodolfo Ruccellai, in 1500, now the Military Headquarters.

One whole side (N.) of the Piazza is occupied by the great Monastery and Church of S. Marco, founded by the Silvestrini, a branch of the Vallombrosans, in 1290, but almost entirely rebuilt for the Dominicans under Michelozzo (1437–52]. It is especially interesting from its associations with Savonarola and Fra Angelico,1 the latter having passed nine years within its walls. The convent was suppressed in 1860.

The convent is now a National Museum of History and Art, and is admirably cared for. In January 2021, the new Sala del Beato Angelico opened with funding from the Friends of Florence. Among the masterpieces are: —

Fra Angelico. The Deposition—one of the finest works of the master, but much repainted. From S. Trinità. Vasari says that in the figure of Nicodemus here is represented Michelozzo, the builder of S. Marco.According to Blashfield: “It is not the figure of Nicodemus, however, which represents Michelozzo, but another figure wearing a black hood.”1Giorgio Vasari, Lives, vol. 2, p. 19, note 47.

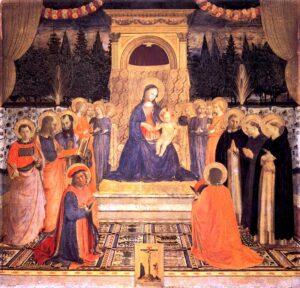

But exquisite; and admirable above all is the picture of the High Altar in that church; for besides that the Madonna in this painting awakens devotional feeling in all who regard her, by the pure simplicity of her expression; and that the saints surrounding her have a similar character; the predella,2Only two of the original nine panels remain at San Marco. The rest have been dispersed. in which are stories of the martyrdom of San Cosimo, San Damiano, and others, is so perfectly finished, that one cannot imagine it possible for any thing to be executed with greater care, nor can figures more delicate;, or more judiciously arranged, be conceived.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 2, pp. 35–36.

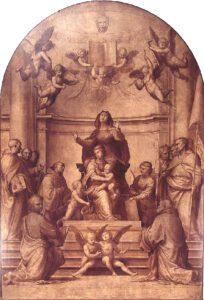

Fra Bartolommeo Room

The Virgin and Child throned, with Saints, in bistre; ordered by Pietro Soderini for the council-hall of the Republic, and left unfinished at the death of the artist in 1517. The Medici placed it in S. Lorenzo, whence it was brought here. S. Anna, who was supposed to have saved Florence from the tyranny of the Duke of Athens, is the principal figure, standing behind the Virgin. S. Reparata kneels, bearing a palm-branch.

Had this grandiose creation been finished, it would have been the chef-d’oeuvre of Fra Bartolommeo. Its interest is great, as revealing the growth of such a piece from its embryo to the first stage of completion. We can trace each step taken by the artist, from the moment of planning to that of putting in the contours and shadows. But there is something more than science and method to be discerned, and that is the inspired air of S. Anna, the weight, the dignity, and proud bearing of the Saints, the masculine strength of the art evolved.

Crowe and Cavalcaselle, New History of Painting in Italy, vol. 3, pp. 455–56.

The perfect architectonic idea is not only everywhere clearly set forth in a lively manner, but also filled with the noblest individual life.

Jacob Burckhardt, Cicerone, pp. 125–26.

The graceful Cloister is first entered. The garden is full of roses, iris, and myrtle. It is surrounded by frescoes of a later date than Savonarola, but amid them are six exquisite works of Fra Angelico: —

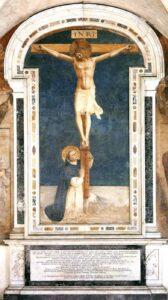

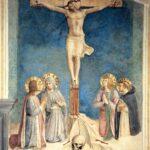

- The Crucifixion, with S. Dominic kneeling at the foot of the cross, 1441-42.

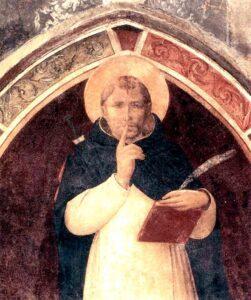

- S. Peter Martyr, with the knife of his martyrdom buried in his shoulder, and his finger on his lips, expressing the enforced silence of the cloister. “It is difficult to say whether Angelico did not express the obligation of silence more by the glance than by the gesture.” This is above the door of the Sacristy.

- The Discipline of the Cloister (much injured), expressed by S. Dominic with a book and a cat-of-nine-tails.

- The Resurrection, expressive of the reward of monastic life.

- Two Dominicans welcoming our Saviour in a pilgrim’s dress.

No scene more true, more noble, or more exquisitely rendered than this can be imagined.

Crowe and Cavalcaselle, New History of Painting in Italy, vol. 1, pp. 579–80.

- A portrait of S. Thomas Aquinas, as the glory of the Dominicans.

The Funeral of S. Antonino is by Matteo Rosselli (1578–1650).

It is in this cloister that his fighting successor, Girolamo Savonarola, is described as sitting in his early convent life, discoursing under a damask-rose tree—“sotto un rosajo di rose damaschine.”

Opening from the cloister (east) is the Great Refectory, which contains a good fresco by Giov. Ant. Sogliani (1492–1544) of the angels bringing food to S. Dominic and his penniless brethren at S. Sabina in Rome. Above is a Crucifixion by Fra Bartolommeo.

The Chapter-House has a grand Crucifixion by Fra Angelico. Many saints, including the Medicean patrons SS. Cosmo and Damiano and the Fathers of the Church, are introduced into this picture, and gaze up at the Saviour with wonder, sorrow, and ecstasy. Around it is a framework of prophets and sibyls, and beneath is S. Dominic, from whom springs the tree of the Order, branching forth into many saints.

The figure of the Saviour is that in which Fra Giovanni [i.e. Angelico] most perfectly gave expression to the resignation and suffering of Christ.

Crowe and Cavalcaselle, New History of Painting in Italy.

In point of religious expression, this is one of the most beautiful works of art existing.

Franz Kugler, Handbook of Painting, vol. 1, p. 167.

The great Crucifixion in the Capitolo is in excellent preservation, and a very singular composition. The tree of life, with its fruit of salvation, the Crucified Messiah, stands in the midst; to the left, the Virgin faints in the arms of S. John, attended by the Maries, &c.; to the right, a whole host of the Christian Fathers and doctors are grouped in adoration, a most noble company, full of variety and individuality in countenance and attitude, yet collectively one in the concentration of their interest on Christ. The heads are full of character, that of S. Jerome kneeling is peculiarly grand; the breadth and dignity of the drapery is surprising. The background was originally of rich ultra-marine, now picked off. The whole is surrounded by a fresco framework of Prophets, Sibyls, and Saints, among whom the pelican, the ancient symbol of our Saviour, looks down upon the cross. A row of Saints and Beati of the Dominican Order, branching from the patriarch in the centre, runs like a frieze below.

Lord Lindsay, Christian Art, vol. 2, p. 242.

To understand how profoundly every part of this grand composition has been meditated and worked out, we must bear in mind that it was painted in a convent dedicated to S. Mark, in the days of the first and greatest of the Medici, Cosimo and Lorenzo, and that it was the work of a Dominican friar, for the glory of the Dominican Order. In the centre of the picture is the Redeemer crucified between the two thieves. At the foot of the cross is the usual group of the Virgin fainting in the arms of S. John the Evangelist, Mary Magdalene, and another Mary. To the right of this group, and the left of the spectator, is seen S. Mark as patron of the convent, kneeling and holding his Gospel; behind him stands S. John the Baptist, as protector of the city of Florence. Beyond are three martyrs, S. Laurence, S. Cosmo, and S. Damian, patrons of the Medici family. The two former, as patrons of Cosimo and Lorenzo de’ Medici, look up at the Saviour with devotion; S. Damian turns away and hides his face. On the left of the cross we have the group of the founders of the various Orders—first, S. Dominic, kneeling with hands outspread, gazes up at the Crucified; behind him S. Augustine and S. Albert the Carmelite, mitred and robed as bishops; in front kneels S. Jerome as a Jeronymite hermit, the Cardinal’s hat at his feet; behind him kneels S. Francis; behind S. Francis stand two venerable figures, S. Benedict and S. Romualdo; and in front of them kneels S. Bernard, with his book; and, still more in front, S. John Gualberto, in the attitude in which he looked up at the crucifix when he spared his brother’s murderer. Beyond this group of monks Angelico has introduced two of the famous friars of his own community: S. Peter Martyr kneels in front, and behind him stands S. Thomas Aquinas; the two, thus placed together, represent the sanctity and learning of the Dominican Order, and close this sublime and wonderful composition. Thus considered, we may read it like a sacred poem, and every separate figure is a study of character. I hardly know anything in painting finer than the pathetic beauty of the head of the penitent thief, and the mingled fervour and intellectual refinement in the head of S. Bernard.

It will be remembered that, in this group of patriarchs, “Capi e Fondatori de’ Religiosi,” S. Bruno, the famous founder of the Carthusians, is omitted. At the time the fresco was painted, about 1440, S. Bruno was not canonised.

Anna Jameson, Legends of the Monastic Orders, pp. xxx-xxxi.

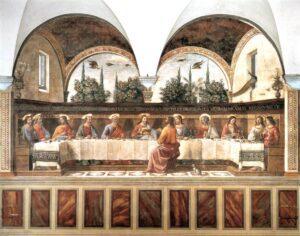

A passage leads to the Smaller Refectory, which contains a Cenacolo by Ghirlandajo, a noble picture with beautifully rendered details of birds and flowers seen through the open arcades behind the figures.

The Last Supper is an excellent example of the natural reverence of the artist. The main idea with him has been the variety, the brilliancy, the material charm of the scene, which finds expression, with irrepressible generosity, in the accessories of the background. Instinctively he imagines an opulent garden—imagines it with a good faith which quite tides him over the reflection that Christ and his disciples were poor men and unused to sit at meat in palaces. Great full-fruited orange-trees peep over the wall before which the table is spread, strange birds fly through the air, and a peacock perches on the edge of the partition and looks down on the sacred repast. It is striking that, without any religious purpose at all intense, the figures, in their varied naturalness, have a dignity and sweetness of attitude which admits of numberless reverential constructions.

Henry James, Italian Hours, p. 410.

Here is the entrance to the stairs leading to the cells. At their head is a lovely Annunciation, 1442-43, by Fra Angelico.

The Virgin sits in an open loggia resembling that of the Florentine church of L’Annunziata. Before her is a meadow of rich herbage covered with daisies. Behind her is seen, through a door at the end of the loggia, a chamber with a single grated window, through which a star-like beam of light falls into the silence.

John Ruskin, Modern Painters, vol. 2, p. 169.

Facing this is S. Dominic embracing the Cross. The most perfect works of Fra Angelico may be studied here, where they were painted with affectionate care on the walls of his convent home and in the cells of his friends and companions.

Fra Giovanni was in his manner of life simple and most holy; and the following may be taken as an indication of his scrupulous subjection to duty. One day, Nicholas V. having invited him to dinner, he refused to eat meat, because he had not previously obtained the required permission of his superior, forgetting, in his unquestioning obedience, the authority of the Pope to release him from it. He avoided all worldly business, and living in purity and holiness, he so loved the poor, as, I believe, his soul now loves heaven; he worked continually in his art; nor would he ever paint other things than those which concerned the saints. He might have been rich, but he cared not for riches; nay, he was wont to say, that true riches consist entirely in being content with little. He might have had command over many, and would not, saying that to obey others was less troublesome and less liable to error. It was in his choice to have honour and dignities in his convent and beyond it; but they were valueless to him, who affirmed that the only dignity he sought was to avoid Hell and to reach Paradise; and what dignity is to be compared to that which all ecclesiastics, and indeed all men, ought to seek, and which is found only in God and in a virtuous life? He was most kind, and living soberly and chastely, he freed himself from the snares of the world, frequently repeating that the Painter had need of quiet and of a life undisturbed by cares, and that he who does the things of Christ should always be with Christ. That which appears to me a very wondrous and almost incredible thing is, that among his brethren he was never seen in anger: and it was his wont, when he admonished his friends, to do it with a sweet and smiling gentleness. To those who asked for his works, he invariably answered, with incredible benignity, that they had only to obtain the consent of the Prior, and then he would not fail to do their pleasure. In fine, this monk, whom it is impossible to praise overmuch, was in his words and works humble and modest, and in his pictures of ready skill and devout; and the saints which he painted have a more saint-like air and semblance than those of any other painter whatever. It was his rule not to retouch or alter any of his works, but to leave them just as they had shaped themselves at first; for he believed, and he used to say, that such was the will of God. It is supposed that Fra Giovanni never took up a brush without a previous prayer. He never painted a crucifix without bathing his own cheeks with tears, and therefore it is that the expressions and attitudes of his figures clearly demonstrate the devotion of his great soul to the Christian religion. He died in 1455, in the sixty-eighth [sic.] year of his age.3Bezzi text says fifty-eighth year. Fra Angelico’s dates are c. 1395–1455.

Giorgio Vasari, Life of Giovanni Angelico, Trans. Bezzi, pp. 15–16.

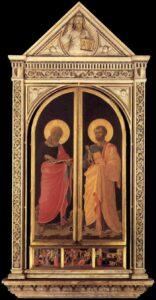

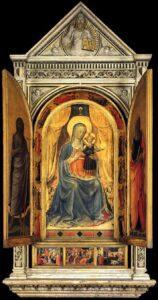

The Dormitory of the convent is divided into cells, with a passage down the middle. Each cell has its own exquisite fresco. Turning to the left, those in the cells on the left are all by Fra Angelico, those on the right, by his brother, Fra Benedetto. In the corridor, on the right, is a large fresco, once a tabernacle, of the Virgin and Child enthroned, with, on the right, SS. Mark, Thomas Aquinas, Laurence, and Peter; on the left, SS. John the Evangelist, Cosmo and Damian, and Dominic.

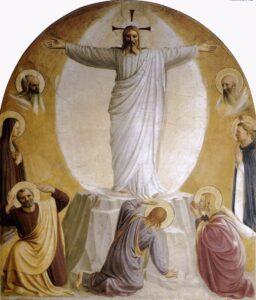

Amongst the most beautiful parts in the frescoes in the cells are:—

No. 5. The figure of S. Catherine, who kneels in the background at the Nativity.

No. 6. The Transfiguration—the figure of the Saviour is sublime.

No. 7. The Saviour buffeted—only the insulting hands appear, and have a very odd effect. The Virgin appears below, and S. Dominic, who is introduced in most of the pictures.

No. 8. The figure of the dazzled Mary looking into the empty tomb at the Resurrection.

No. 9. The humble rapt figure of the Madonna, in the Coronation of the Virgin.

The cells on the other side of this corridor (Nos. 15–23) intended for the “Giovanati” monks who had just passed their noviciate, contain the Crucifixion repeated in each by Fra Benedetto, only the figure of S. Dominic at the foot of the cross is always varied.

At the end of the corridor is (No. 12) the Prior’s Cell, which contains two frescoes of the Madonna and Child by Fra Bartolommeo, painted when the sermons of Savonarola had so impressed him with a religious vocation that he had bidden farewell to the world, and assumed the monastic habit at Prato. Thence he was removed to this convent, where he was induced to resume his pencil, though only for religious subjects.

Here are busts of Savonarola and his friend Girolamo Benivieni, imitations of old terra-cottas, by Girolamo Bastiniani (ob. 1868). Within are two small cells, which are of deep interest as having been occupied by Girolamo Savonarola when Prior. His hair-shirt, rosary, chair, and a fragment from the pile on which he was burnt are preserved here. In a desk, which is an imitation of his own, is a copy of his sermons, and—most interesting—his treatise against the “Trial by Fire,” and upon the desk is his wooden crucifix. The portrait upon the wall is attributed to Fra Bartolommeo.

In the inner cell is a most interesting old picture which belonged to the Buondelmonti family, representing the execution of Savonarola (May 28, 1498). The Ringhiera is represented, with the long platform leading from it by which the scaffold in the piazza was approached. The three suffering monks are seen three times, so as to give the whole scene—(1) being unfrocked; (2) being dragged along the platform; (3) hanging round a pole over the flames.

Savonarola embraced a monastic life in his twenty-second year, choosing the Dominican Order on account of his predilection for S. Thomas Aquinas. In 1490 he was elected Prior of S. Marco, and finding his conventual church too small for the crowds who came to attend his sermons, obtained leave to preach in the cathedral, for “even in winter the square in front of S. Marco was thronged for hours before its doors were opened by disciples wishing for places,”4Sismondi, Hist. Ital., xii. 72.4Sismondi, Hist. Ital., xii. 72. and “tradesmen forbore to open their shops till the Prior’s morning preaching was over.”5Burlamacchi, Vit. Sav., 88, 93.

In order to participate in the benefits of the spiritual food which he dispensed, the inhabitants of the town and neighbouring villages deserted their abodes, and the rude mountaineers descended from the Apennines and directed their steps towards Florence, where crowds of pilgrims flocked every morning at break of day, when the gates were opened, and became the objects of a charity truly fraternal, the citizens vying with each other in the exercise of the duties of Christian hospitality, embracing them in the streets as brothers, even before they were acquainted with their names, while some of the more pious received them by forty at a time into their houses.

When we consider that this enthusiasm continued for seven consecutive years, during which time it was necessary for him to preach separately to men, women, and children, from the impossibility of admitting them all at one time into the cathedral; and all this unheard-of success was obtained amidst the cries of rage of the moderate faction, who denounced him daily at the court of Rome, and threatened him publicly with punishment, we are at a loss which to admire most in Savonarola, his inexhaustible fluency as an evangelical orator, his facility in rising superior to popular fury, or his almost superhuman reliance on that Divine succour which he believed could never fail him.

The eloquence of the pulpit had before this degenerated into disputations purely scholastic, and the preachers most in favour, making a monstrous medley of the Gospel and logic, came, their heads stuffed with all the subtleties of the schools, to perplex the minds of their hearers with barren disputations, while the things of God and of Faith were neglected and forgotten.

Blessed, indeed, were then the poor in spirit; for, when Savonarola burst forth with the abundance and happy choice of his Biblical quotations, it was in these simple souls they re-echoed, like repeated peals of thunder, and the same burning coal appeared to have refined their hearts and purified their lips. . . . The sympathies of the preacher were never more deeply affected than when he spoke to children. He called upon them to reap the fruits of his labours in their day, and to watch over the future destinies of their country; but in the meantime he prepared for this glorious future by adapting to their capacities the great truths of the faith and by suggesting salutary reforms in domestic education. It was solely on the generations placed, so to speak, between infancy and manhood that Savonarola rested his hopes of the future—hopes which he cherished during eight consecutive years with an unparalleled zeal, and which sustained him under the severe trials caused by the implacable hatred of his enemies.

To prepare and secure the triumph of art, poetry, and Christian faith for a new era, which was to open gloriously with the sixteenth century, and at Florence rather than elsewhere, on account of her superior holiness, such was the aim which Savonarola proposed to himself in impregnating the heart and imagination of youth with the exquisite perfume of a tender child-like piety, the fragrance of which is generally prolonged through advancing years. His success so far surpassed his expectations, that he could only himself attribute it to the miraculous intervention of Divine mercy, and he was never more pathetic than when he poured forth his gratitude to the Author of this blessing. The joy he experienced was so great that it seemed an anticipation of his heavenly reward.

Alexis-François Rio, The Poetry of Christian Art, pp. 234–35, 238, 244–45, 250–51.

“In heaven,” said Pius VII., “I shall know the explanation of three great mysteries—the Immaculate Conception, the suppression of the Society of Jesus, the death of Savonarola. War waged round Savonarola in his lifetime: it has never ceased since his death. Saint, schismatic, or heretic, ignorant vandal or Christian artist, prophet or charlatan, champion of the Roman Church or apostle of emancipated Italy which was Savonarola?”

Church Quarterly Review.

One of the longings of Savonarola was to make his convent a school and sanctuary of sculpture and painting consecrated to the service and glory of religion. Hence, perhaps, some of his peculiar power over the minds of the artists of his time.

Sandro Botticelli gave up painting for love of Savonarola, and would have starved without the assistance of Lorenzo de’ Medici and other friends. Two of the Robbias were made priests by his hand, and testified their veneration for him by coining a medal bearing his portrait on one side, and on the other a city with many towers, above which appeared a hand holding a dagger pointing downwards, with the motto, “Gladius Domini sup. terrain cito et velociter.” [the sword of God over the earth, quickly and swift] Lorenzo di Credi spent the latter years of his life in the convent of S. Maria Novella; Fra Bartolommeo became a monk in the convent of S. Mark, and was so afflicted by Savonarola’s death that he gave up painting for four years. Cronaca ceased story-telling, for which he had become famous, and would talk only of Fra Girolamo. Giovanni della Corniole perpetuated his likeness in one of the finest of modern gems. Michelangelo, one of the friar’s constant auditors in his youth, pored over his sermons when an old man, and ever retained a vivid impression of his powerful voice and impassioned gestures, proving that he had profited by his eloquent appeals when he defended the Republic on the slopes of San Miniato.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, pp. 237–38.

To a mind like that of Savonarola, deeply imbued with the religious sentiment, Florentine art acted like sacred music, and bore witness to the omnipotence of genius inspired by faith. The paintings of Angelico appeared to have brought down angels from heaven to dwell in the cloisters of S. Mark, and he felt as if his soul had been transported to the world of the blessed.

Pasquale Villari, Savonarola, vol.1, p.39.

The greatness of Savonarola is to have felt that, in order to save Italian nationality, it was necessary to take the revolution to religion itself.

Edgar Quinet, Révolutions d’Italie, p. 242.

Returning to the head of the stairs, the cell facing the staircase (No. 31) was that occupied by S. Antonino (Pierozzi) for many years, after he was transferred here from the Dominican convent at Fiesole, and before he was raised to the Archbishopric. His vestments, his portrait by Fra Bartolommeo, and a mask of his face are preserved here.

It would be difficult to find in history an example of self-denial more constant, of charity more active, of love to our neighbour more truly evangelical, than S. Antonino. There is scarcely a charitable institution in Florence that he did not either found or revive. To him belonged the praise of changing into an institution of charity that society of the Bigallo which S. Peter Martyr had founded for the extermination of heresy, and which had so often polluted the streets and walls of Florence with blood. From that time forward the officers of the Bigallo, instead of burning and slaying human beings, sought out and succoured neglected orphans. S. Antonino was the founder of the society called “Buoni Uomini di San Martino” who, to this day, fulfil the Christian duty of collecting offerings and of distributing them to the poor of better condition who are ashamed to beg. It would be impossible to recount all he did for the benefit of the people. He was frequently seen traversing the city and surrounding country leading a mule loaded with bread for some and with clothes for others, and bringing relief to the dwellings of the poor which plague or famine had made desolate. His death, which occurred in Florence in 1459, was mourned as a public calamity, and no one ever mentioned his name without reverence.

Pasquale Villari, Savonarola, vol.1, pp. 37–38.

Early Italian artists of earnest purpose indicated by perfect similarity of action and gesture on the one hand, and by the infinite and truthful variation of expression on the other, the most sublime strength, because the most absorbing unity, of multitudinous passion that ever human heart conceived. Hence, in the cloister of S. Mark’s, the intense, fixed, statue-like silence of ineffable adoration upon the spirits in prison at the feet of Christ, side by side, the hands lifted, and the knees bowed, and the lips trembling together.

John Ruskin, Modern Painters, vol. 2, p. 54.

In cell No. 33 is an exquisite little Fra Angelico of the Madonna and Child surrounded by angels, brought from S. Maria Novella, and in the cell within this another small picture of the Coronation of the Virgin.

The sweetness and purity of the Virgin are beyond the sphere of criticism they sink into the heart and dwell there in the dim but holy light of memory, in association with looks and thoughts too sacred for sunshine and “too deep for tears.”

Lord Lindsay, Sketches of the History of Christian Art, vol. 2, p. 242.

Fra Angelico, Crucifixion with the Virgin and Sts Cosmas, John the Evangelist and Peter Martyr (Cell 38), 1441-42

Cell No. 34 has a similar picture of the Adoration of the Magi, with a lovely predella.

The last cell on the right (No. 38), adjoining the church, has an inner chamber approached by steps. An inscription records that it belonged to Cosimo de’ Medici, who built it that he might more intimately converse with S. Antonino and the two brothers Fra Angelico and Fra Benedetto. A portrait of Cosimo by Pontormo was in this cell.6Now in the Uffizi. Here Pope Eugenius IV. lodged in 1432, when he came for the consecration of the church. The frescoes present the Adoration of the Magi and a Pietà.

The Library is a fine room carried on ranges of pillars. It contains a collection of choral-books, brought hither from the Badia, and various suppressed convents. Fourteen of those originally belonging to S. Marco were illuminated by Fra Benedetto. It was this room which witnessed the last striking scene in Savonarola’s convent life.

In the middle of this hall, under the simple vaults of Michelozzi, Savonarola placed the Sacrament, collecting his brethren around him, and addressed them in his last and memorable words: “My sons, in the presence of God, standing before the sacred Host, and with my enemies already in the convent, I now confirm my doctrine. What I have said came to me from God, and He is my witness in heaven that what I say is true. I little thought that the whole city would so soon have turned against me; but God’s will be done. My last admonition to you is this—Let your arms be faith, patience, and prayer. I leave you with anguish and pain, to pass into the hands of my enemies. I know not whether they will take my life; but of this I am certain, that dead, I shall be able to do far more for you in heaven, than living I have ever had power to do on earth. Be comforted, embrace the cross, and by that you will find the haven of salvation.”

The enemy had now got full possession of the convent, and Giovacchino della Vecchia, who commanded the Palazzo guard, threatened to destroy everything with his artillery if the commands of the Signory were not immediately obeyed. These were, that, on the faith that their persons would be safe, Fra Girolamo, Fra Domenico, and Fra Salvestro should be delivered up. But Malatesta Sacramoro, the same who had offered to pass through the fire, began to play the part of Judas; he had a conference with the Compagnacci, and advised them to bring a written order. While they were sent to obtain it from the Signory, Savonarola confessed to Fra Domenico, received the communion from him, and prepared to give himself up with Fra Domenico. Fra Salvestro had concealed himself, and in the disturbance it was not easy to find him.

A singular incident occurred about this time. Girolamo Gini, a follower of the Friar, who had long desired to assume the Dominican dress, was that evening at vespers; and scarcely had the tumult begun when he armed himself to defend the convent. When Savonarola ordered him to lay aside his arms the good citizen obeyed; but he ran through the cloisters, facing the enemy, wishing, as he said, to meet death for the love of Jesus Christ; and, having been wounded, he entered the Greek library, his head streaming with blood, threw himself on his knees before Savonarola, and humbly asked that the convent dress might be given to him a request which was immediately granted.

Pasquale Villari, History of Girolamo Savonarola, vol. 2, pp. 300–01.7Three of the sons of Andrea della Robbia were with Savonarola at this time, and the best contemporary account is that of Fra Luca—Marco della Robbia.

Descending the stairs and turning to the right, we enter the Second Cloister. Here, on the left, is the Dormitory of the Novices—“I nostri Angioli” [our angels]—as Savonarola was wont to call them. It is now used for the meetings of the Accademia della Crusca. Five of its eight lunettes are by Fra Bartolommeo.

The Convent Garden is especially connected with an incident in the life of Savonarola. Here, too, he was wont of cool summer evenings to walk with his friars, and expound.

After attending the mass of S. Marco, as Lorenzo de’ Medici now and then did, he would walk in the convent garden; and it was known among the fraternity that he would have been well pleased had the Prior sometimes joined him in his walk, and thus have given him opportunities of evincing his regard. Burlamacchi mentions an occasion on which a monk in the interest of Lorenzo went to apprise the Prior that the Magnifico was walking in the garden. “Has he asked for me?” was his reply. “No, father,” said the monk. “Let him then pursue his devotions undisturbed,” rejoined he, and remained tranquil in his cell. “This man is a true monk,” said Lorenzo, “and the only one I have known who acts up to his profession.”

John Harford, Life of Michelangelo, vol. 1, p. 132.

The garden became a school of fine arts for young painters and sculptors in the XV. and XVI. c., and whilst studying here they were supported by Lorenzo the Magnificent, who collected in the gardens of the convent endless fine works of sculpture.

The Church of S. Marco is in itself little important; but here the friends and lovers of Savonarola waited and prayed while he went forth from them to the ordeal. On the façade, which is modern, is a statue of S. Dominic with his dog. Over the entrance inside is the wooden crucifix of Giotto, which is believed to have established his supremacy over Cimabue, and caused Dante to write: —

O vanagloria dell’ umane posse,

Com’ poco verde in su la cima dura

Se non è giunta dall’ etadi grosse!

Credette Cimabue nella pintura

Tener lo campo, ed ora ha Giotto il grido,

Sì che la fama di colui s’ oscura.

O thou vain glory of the human powers.

How little green upon thy summit lingers,

If’’t be not followed by an age of grossness!

In painting Cimabue thought that he

Should hold the field, now Giotto has the cry,

So that the other’s fame is growing dim

Dante Purgatorio 11:91–96. Trans. Longfellow.

O thou vain glory of the human powers.

How little green upon thy summit lingers,

If’’t be not followed by an age of grossness!

In painting Cimabue thought that he

Should hold the field, now Giotto has the cry,

So that the other’s fame is growing dim.8O vanagloria dell’ umane posse, / Com’ poco verde in su la cima dura / Se non è giunta dall’ etadi grosse! / Credette Cimabue nella pintura / Tener lo campo, ed ora ha Giotto il grido, / Sì che la fama di colui s’ oscura.

Dante Purgatorio 11:91–96. Trans. Longfellow.

In the Chapel of S. Antonino, in the left transept, the good bishop is buried, whose characteristics were charity, humility, gentleness, and love. The frescoes of his funeral, &c., are by Passignano, the bronze reliefs of his history by Partigiani.

On the left of the nave are the graves of three learned men, Girolamo Benivieni, ob. 1542;9His portrait, by Lorenzo di Credi, is at Cobham Hall, Gravesend. Poliziano, ob. 1494; and Pico della Mirandola, ob. 1494. The inscription to Pico is on the wall: —

D. M. S.

Johannes jacet hic Mirandula caetera norunt

Et Tagus et Ganges forsan et Antipodes

ob. an. Sal. MCCCCLXXXXIIII. vix. ad. XXXII.

Hieronimus Benivienus ne disiunctus post

mortem locus ossa separet quorum animas

in vita conjunxit amor hoc humo

supposita peni curavit.

Here lies Giovanni Mirandola; known both at

the Tagus and the Ganges [rivers] and maybe even the antipodes.

He died in 1494, and lived for thirty-two years.

To prevent the bones of those whose souls

were joined by Love while living

from finding separate places after death,

Girolamo Benivieni provided for this grave

where he too is buried.

D. M. S.

Johannes jacet hie Mirandula caetera norunt

Et Tagus et Ganges forsan et Antipodes

ob. an. Sal. MCCCCLXXXXIIII. vix. ad. xxxii.

Hieronimus Benivienus ne disiunctus post

mortem locus ossa separet quorum animas

in vita conjunxit amor hoc humo

supposita peni curavit.10Here lies Giovanni Mirandola; known both at the Tagus and the Ganges [rivers] and maybe even the antipodes. He died in 1494, and lived for thirty-two years. Girolamo Benivieni, to prevent separate places from disjointing after death the bones of those whose souls were joined by Love while living, provided for this grave where he too is buried.

Another tablet, brought from above his grave in the presbytery, and placed below that of Pico, is that of Politian, priest and canon of the cathedral: —

Politianus

in hoc tumulo jacet

Angelus unum

qui caput et linguas

res nova tres habuit

obiit an. MCCCCLXXXXIV.

Sept. xxiv. aetatis

XL.

Poliziano

lies in this tomb,

the angel who had

one head and,

what is new, three tongues.

He died September 24,1494,

aged 40.

Politian died Sept. 24, 1494, “with as much infamy and abuse as a man could well be loaded with.” He was accused of numberless vices and of enormous profligacy; but the true cause of all this hatred was rather to be traced to Piero de’ Medici having become so universally detested, and to Politian’s death having occurred near the time when Piero and his adherents were expelled. Nor were these angry feelings at all mitigated by the knowledge that the last words that fell from the lips of the illustrious poet and accomplished scholar were words of contrition. He had requested that his body might be buried in a Dominican dress in the Church of S. Mark, where, in fact, his ashes repose by the side of those of Pico della Mirandola, who died the very day that Charles VIII. entered Florence. Pico had also for some time expressed a desire to assume the dress of the friars of S. Mark, but having hesitated too long, his wish could not be fulfilled, as death carried him off at the early age of thirty-two. While on his death-bed, he asked Savonarola not to allow him to go down to the tomb without first having been clothed in that habit.11The tombs were opened in 2007. Tests confirmed that both Pico and Poliziano died of arsenic poisoning.—Ed.

The end of these two illustrious Italians recalled to mind the last hour and confession of the Magnificent; for to many it appeared that the Medicean society, on leaving the world, had indeed to acknowledge their crimes, and ask absolution from the people they had so grievously oppressed, and from the friar who might be considered the living and speaking representative of that people. Singular it was, that they all looked to that Convent of S. Mark, from whence had issued the first cry of liberty, the first resistance, and the first accusations against the tyranny of the Medici.

Pasquale Villari, Savonarola, vol.1, pp 231–32.

The mosaic of the Madonna on the right was brought from the Oratory of the Porta Santa in 1609, [1509?] and presented by Michelangelo.12Unlikely. Michelangelo died in 1564. Hare repeats the erroneous date found in Horner, Walks in Florence, vol. 2, p. 176.—Ed. A stone beneath the pulpit marks the vault of the Lapi13Arms: Gules, a fess, argent; on a chief, a lion passant, sable. family, of whom was Niccolò, rendered famous by the Romance of Azeglio.

The Via del Maglio, now Lamarmora, which leads from the Piazza S. Marco to the site of the walls, is the place where the young Florentines used to play at maglio in the XV. c. The name of the game remained to the street and the convent of S. Domenico del Maglio.

On the east of the Piazza S. Marco is the Institute di Studi Superiori, containing the Museo Indiano. Here also are the Mineralogical and Geological Collections belonging to the University. No. 11 is the house where Bianca Cappello and her husband took refuge after their flight from Venice. The house at the corner of the Via degli Arazziere is known as La Villa della Lima, having been built in 1780 by the Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo for his mistress, Livia Malfatti.

At the S. corner of the Via Ricasoli14Formerly Via del Cocomero, re-named from the patriot Bettino Ricasoli, who was born at No. 9 in 1808. and the Piazza S. Marco is the ancient Ospedale di S. Matteo, now the Accademia delle Belle Arti (see next section 3.6).