8.2: San Miniato al Monte

From the Porta S. Miniato (S. Miniato in Monte).

This gate is situated close under the hill of Oltr’ Arno, and an avenue of cypresses leads in a few minutes up the steep ascent called Monte alle Croci to the church. This “Via Crucis,” though it does not look it, is one of the oldest in existence. On the right of the way a shrine with a picture commemorates a touching incident in the life of S. Giovanni Gualberto, founder of the Vallombrosans.

Giovanni Gualberto was born at Florence, of rich and noble lineage. When he was still a young man, his only brother, Hugo, whom he loved exceedingly, was murdered by a gentleman with whom he had a quarrel. Gualberto, whose grief and fury were stimulated by the rage of his father and the tears of his mother, set forth in pursuit of the assassin, vowing a prompt and terrible vengeance.

It happened that, when returning from Florence to the country-house of his father on the evening of Good Friday, he took his way over the steep, narrow, winding road which leads from the city gate to the Church of San Miniato-del-Monte. About half-way up the hill, where the road turns to the right, he suddenly came upon his enemy, alone and unarmed. At the sight of the assassin of his brother, thus, as it were, given into his hand, Gualberto drew his sword. The miserable wretch, seeing no means of escape, fell upon his knees and entreated mercy; extending his arms in the form of a cross, he adjured him by the remembrance of Christ, who had suffered on that day, to spare his life. Gualberto, struck by a sudden compunction, remembering that Christ when on the cross had prayed for his murderers, stayed his uplifted sword, trembling from head to foot; and after a moment of terrible conflict with his own heart, and a prayer for Divine support, he held out his hand, raised the suppliant from the ground, and embraced him in token of forgiveness. Thus they parted; and Gualberto proceeding on his way in a sad and sorrowful mood, every pulse throbbing with the sudden revulsion of feeling, and thinking on the crime which he had been on the point of committing, arrived at the Church of San Miniato, and entering, knelt down before the crucifix over the altar. His rage had given way to tears, his heart melted within him; and as he wept before the image of the Saviour, and supplicated mercy because he had shown mercy, he fancied that, in gracious reply to his prayer, the figure bowed its head. This miracle, for such he deemed it, completed the revolution which had taken place in his whole character and state of being. From that moment the world and all its vanities became hateful to him, he felt like one who had been saved upon the edge of a precipice; he entered the Benedictine Order, and took up his residence in the monastery of San Miniato. Here he dwelt for some time a humble penitent; all earthly ambition quenched at once with the spirit of revenge. On the death of the abbot of San Miniato he was elected to succeed him, but no persuasions could induce him to accept the office. He left the convent, and retired to the solitude of Vallombrosa.

Anna Jameson, Legends of the Monastic Orders, pp. 118–119.

The cypress avenue ends in the Church of S. Salvatore al Monte, built from designs of Simone del Pollajuolo, known as Il Cronaca,1“The Chronicle,” from his habit of narrating all that he saw, in minutest detail. in 1489. Its position is beautiful, and its stately simplicity so delighted Michelangelo that he used to call it “La Bella Villanella.” The founder of the church and of the important Franciscan convent adjoining is buried in the choir, with Giovan Battista Adriani, the historian of Florence from 1536 to 1574. To this church, by the advice of Tanai de’ Nerli, was exiled the bell of S. Marco, which sounded the alarm when the convent was attacked and Savonarola taken prisoner. It first rang here for the funeral of the same Tanai de’ Nerli, who is buried in the church. Later it was restored to S. Marco.

Beneath this church, the terraced Piazzale Michelangelo, designed by Giuseppe Poggi in 1875, contains copies of several of his statues including a bronze David and statues from the Medici tombs at San Lorenzo. Its view over the city and the gardens with which it is embroidered is one of the noblest in Italy. Opposite the Piazzale is a loggia with three arched bays originally intended to house additional Michelangelo copies. It is now a restaurant-cafe. The small fountain fronting the loggia boasts a marble plaque memorializing Poggi: “Giuseppe Poggi Architetto (sig photo) Fiorentino Volgetevi Attorno ecco il suo monumento.” (Giuseppe Poggi Florentine architect. Turn around, here is his monument.)2The inscription recalls the epitaph of Sir Christopher Wren (1632–1723) at St. Paul’s Cathedral, London: “Si monumentum requiris circumspice” (“If you would seek my monument, look around you.)]

The view from San Miniato is best seen towards sunset. From an eminence, studded by noble cypresses, the Arno meets the eye, reflecting in its tranquil bosom a succession of terraces and bridges, edged by imposing streets and palaces, above which are seen the stately cathedral, the church of Santa Croce, and the picturesque tower of the Palazzo Vecchio, while innumerable other towers, of lesser fame and altitude, crown the distant parts of the city and the banks of the river, which at length—its sinuous stream bathed in liquid gold—is lost sight of amidst the rich carpet of a vast and luxuriant plain, bounded by lofty Apennines.

Directly opposite to the eye rises the classical height of Fiesole, its sides covered with intermingled rocks and woods, from amidst which sparkle innumerable villages and villas.

J. S. Harford, Life of Michael Angelo, vol. 2, pp. 19–20.

To the right are some of the fortifications which Michelangelo raised in 1529, and which in a certain sense may be regarded as his greatest work, for they enabled Florence to stand “a spectacle to heaven and earth, the one spot of all Italian ground which defied the united powers of Pope and Caesar.”

Within these fortifications stands the beautiful Church of S. Miniato, founded in honour of the Florentine martyr who is said to have taken refuge for a time in the forest which then covered this hill, and who suffered under Decius in the third century on the spot where the church now stands.

According to the Florentine legend, S. Minias or Miniato was an Armenian prince serving in the Roman army under Decius. Being denounced as a Christian, he was brought before the emperor, who was then encamped upon a hill outside the gates of Florence, and who ordered him to be thrown to the beasts in the Amphitheatre. A panther was let loose upon him, but when he called upon our Lord he was delivered; he then suffered the usual torments, being cast into a boiling caldron, and afterwards suspended to a gallows, stoned, and shot with javelins; but in his agony an angel descended to comfort him, and clothed him in a garment of light; finally he was beheaded. His martyrdom is placed in the year 254.

Anna Jameson, Sacred Art, vol. 2, p. 649.

S. Miniato al Monte, set firmly on a marble stylobate, looks beautifully out N.W. over the valley of the Arno, lifting its façade of A.D. 1491 in three sections, all faced with black (Verde di Prato) and white marble. The lowest section consists of a relieved arcade of five arches—one, three, and five being pierced with square doors. Above this succeeds a section divided vertically into three compartments by fluted marble pilasters, a small square window flanked by little columns resting on lions’ heads occurring in the central one. There are triangular throw-offs for the aisles. Above the little window are doves in mosaic. The Pediment is enriched with a golden mosaic representing the Saviour seated between the Virgin and San Miniato, the latter holding in his hand a crown. At either extremity stands a small figure, as if supporting the roof, and at the apex occurs a dark marble Greek cross between six candelabra. As an antefixa there is the gilded eagle clutching bales of wool, the emblem of the Calimala guild, which erected this facade. The mosaics were restored, in 1388, by Maestro Zaccharia, and by Baldovinetti in 1481.

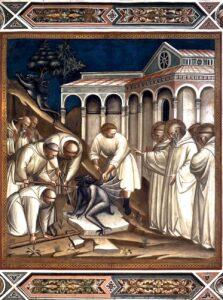

Michelozzo, Chapel of the Crucifixion, c. 1448 (sig photo)

On entering its cool twilight by the central door, a broad band of panelled mosaic pavement extends up the middle of the church, which is seen at a glance to consist of nave and aisles, with a loftily raised choir terminating in an apse. A second glance shows us that the building divides into nine bays of round arches, or three sections of three apiece. The mosaic path (which an inscription says was laid in 1207 by Abbot Joseph) is also seen to lead directly forwards to the little chapel built for Piero de’ Medici (son of Cosimo, and Lorenzo’s father), by Michelozzo (1448), in order to enshrine a marvellous crucifix which was believed to have bowed its head to San Giovanni Gualberto, as marking approval of his generosity in sparing his brother’s murderer. This chapel consists of a cylindrical arch rising from a frieze and cornice carried on two columns and two fluted pilasters. The exterior of the arch is decorated with overlapping scale-tiles, red, white, and green, and at the crown occurs an eagle. Within it is beautifully panelled with octagons, squares, and rosettes in Della Robbia ware, thus forming an elaborate canopy for the Reliquary. The frieze is prettily inlaid in black and white marble with a continuous design made up of the three armorial feathers of the Medici and the word semper.

Above the altar table are eight Giottesque panels representing the Annunciation, the Washing of the Feet, the Last Supper, the Betrayal, the Buffeting, the Scourging, the Resurrection, and the Ascension. The two saints at the sides are San Giovanni Gualberto as a Benedictine, and San Miniato. The whole chapel is enclosed by a light iron grille.

A broad flight of sixteen marble steps now occurs in each aisle, R. and L., leading directly up to a transverse open passage running in front of the choir, which, however, is screened off by an exquisite “transenna” panelled out in fourteen sections of marble mosaic and relief-designs, and interrupted by three separate entrances to the choir, corresponding to those in the façade of the church. This passage was for the neophytes, who might not go further. On the right is seen the square marble pulpit by Alberti, richly inlaid, and carried partly on the choir-screen and in front on two columns. The lectern projects on the wings of an eagle sitting on the head of a saint, who stands upon a bracketed lion.

The deep choir is furnished with two sets of R. and L. concentric stalls richly inlaid by Domenico da Gaiole (1466–70) with devices of crowns, palms, and eagles of the Calimala. The semicircular apse around the high-altar has an arcade of five arches, as in the façade, carried on black marble columns with white marble caps, between which occur (for windows) deep vertical and quadrangular recesses ten feet in length, filled with narrow sheets of Serravezza marble, the violet veins of which show rich effects when the sun falls upon them from without. Above the frieze and cornice of this arcading succeeds the vault, entirely covered with the mosaic of (?) the tenth century, with a date of 1297 in Roman numerals marking one of its restorations. The subject is again the Saviour in the conventional throned attitude, holding the book in his left hand and blessing with his right the Virgin, beside whom is a palm-tree, for Judea. On his left is seen San Miniato dressed as an Armenian prince offering his crown. His name in semi-gothic lettering is beside him.

At the right and left extremities of the choir-aisles are likewise altars adorned with more or less damaged fourteenth-century paintings. Near the sacristy door is a panel attributed to Agnolo Gaddi.

Spinello Arentino, The Miraculous Rescue of Placidus from Drowning, 1388 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Spinello Arentino, The Funeral of St Benedict, 1388 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

Spinello Arentino, St Benedict’s Prayer Enables the Monks to Lift the Stone on Which the Devil Is Sitting, 1388 (photo via Web Gallery of Art)

The sacristy is a square chamber, entirely covered, vault and walls, with frescoes representing scenes and episodes in the life of S. Benedict by Spinello Aretino and Niccolò di Piero Gerini for the heir of Benedetto di Nerozzo degli Alberti, a rich exiled merchant.

Not being distinguished from the others by costume, it was necessary to bring out the superiority of the main figure in another way. Here Spinello was in his element, and no one has ever invested Saint Benedict with so much majesty, either in action or in rest. He knew how to preserve this righteous majesty in death, as can be seen in the fresco where he is represented lying on his funeral bed. . . . This group of monks reciting the funeral service in front of his stiffened body is no less admirable either in terms of ordering or expression, which is both intense and contained. . . . There is a section, the most poorly lit of all, in which Spinello seems to have wanted to rival Giottino for sweetness of expression: it is the one where we see Saint Moor and Saint Placide handed over by their parents to the hands of Saint Benedict.

In the Tabernacle is a canvas picture of the church. It is attributed to Antonio di Francesco (early fifteenth century).

The crypt, which lies five feet below the level of the body of the church, is composed of a little forest of pillars of various marbles, some fluted and some plain, resting on square bases and having a variety of capitals. They are, in fact, distributed in seven bays across the church by five bays deep, all cross vaulted, interrupted at the sides by the huge columns of the choir-aisles. The apse is screened off by an iron grille, behind which stands the altar on a raised stair. The pavement is made of sepulchral slabs.

Returning to the nave, we notice that there is no triforium, and the clear-storey, almost at the springing of the roof, consists of single round-headed lights deeply splayed; while in the façade or west wall is one square central light, and R. and L. splayed round holes. The illumination, therefore, is both primitive and limited.

From the left or N. aisle is entered the Chapel of San Jacopo. It was built to receive the tomb of James, Cardinal of Portugal, whose “stemma” and hat are sculptured over the entrance. He was nephew of King Alfonso, and died while visiting Florence in 1459, and Bishop Alviano of Florence raised this small square chapel, full of beautiful things, in his honour, at the hands of Antonio Mannetti and Luca della Robbia, whose four medallions (Moderation, Chastity, Strength, and Prudence), set in a chequer ground of green, white, and black tiles, adorn the vault. The altarpiece on the north wall is a copy of Pollaiolo, either Anthony or Piero, of the original Three Saints, now removed to the Uffizi. On the eastern wall is the exquisite work of Antonio Rossellino, which Perkins considered to rank only next below that of the Marsuppini tomb in Santa Croce, and that of Leonardo Bruni, made by his brother Bernardo.

Antonio Rossellino, Cardinal of Portugal Tomb, 1466 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The dead man lies as if asleep on his marble bier, with a sweet and placid countenance. Two seated children support the bier at either end. An angel above holds a crown of glory. Still higher are other angels and a circular alto-relievo of the Madonna and Child.

Susan and Joanna Horner, Walks in Florence and its Environs (1884), vol. 2, p. 385.

Among his other admirable virtues, Jacopo di Portogallo determined to preserve his virginity, though he was beautiful above all others of his age….In this mortal flesh he lived as though he had been free from it—the life, we may say, rather of an angel than a man. And if his biography were written from his childhood to his death, it would be not only an ensample but confusion to the world. Upon his monument the head was modelled from his own, and the face is very like him, for he was most lovely in his person, but still more in his soul.

At the head and foot of the sarcophagus, upon which lies the marble figure of the young cardinal, are mourning genii, and upon either end of the highly-ornamented entablature two kneeling angels, holding in their hands the crown of virginity and the palm of victory. Heavy looped curtains (the only faulty feature in this exquisite monument) fall from the top of the arch above it on either side of a roundel, in which is a most lovely Madonna and Child in alto-relief.

Cardinal James, of the royal house of Portugal, who lies here, having lived from his earliest years with peculiar sanctity, as befitted one who was intended to become a priest, was sent to Perugia at the age of nineteen to study canon law. Though only twenty-six at the time of his death, he had received a cardinal’s hat from Pope Calixtus III., and been appointed ambassador from the Florentine Republic to the Court of Spain. He was of a most amiable nature, a pattern of humility, and an abundant fountain of good, through God, to the poor; discreet in providing for his servants, modest in ordering his household, an enemy of pomp and superfluity, keeping that middle way in everything which is the way of the blessed. He lived in the flesh, as if he was free from it, rather the life of an angel than a man, and his death was holy as his life had been.3Vespasiano Bisticci, Vite di Uomini lllustri del Secolo xv.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, p. 205.

Another prince of the same royal house, Don Francesco, was buried here in 1611.

To the left of the entrance is the feeble monument of Giuseppe Giusti, the liberal poet, 1809–50. Pietro Thouar, the educationalist, is also buried in the church.

And now let us enjoy the enchanting prospect from the door. For yonder, immediately below us to the right, lies Florence in all her beauty, with her Duomo set calmly upon her like a dim red crown, while beyond and behind, flank after sloping flank of purple, and fainter purple, mountains descend to the scented plain, as it were, like the Magi of old, on bending knees: and to left, again, ridge after green ridge of villa-crowned hill succeeds in carrying the eye onward and upward to the lofty Apennines and the sunset.

Between these two groups, down in the cool hollow of the valley, extends the long whitish line of palaces of the Lung’ Arno, where the river course flows arrow-like seaward. Above all the heaven is blue and the air is fragrant with blossoms and sweet with the praise of birds. Close to us on our left, the multitudinous dead of Florence sleep in peace.

Near the church is the old Episcopal Palace built by Bishop Andrea Mozzi in 1294, and finished by Bishop Antonio d’Orso in 1320. The fine old tower is a rebuilding by Baccio d’ Agnolo in 1518. All around are graves decorated with flowers on All Saints’ and All Souls’ Day. The view is glorious, especially at sunset.

Let us suppose that the Spirit of a Florentine citizen (whose eyes were closed in the time of Columbus) has been permitted to revisit the glimpses of the golden morning, and is standing once more on the famous hill of San Miniato…. It is not only the mountains and the westward-bending river that he recognises; not only the dark sides of Mount Morello opposite to him, and the long valley of the Arno that seems to stretch its grey low-tufted luxuriance to the far-off ridges of Carrara; and the steep height of Fiesole, with its crown of monastic walls and cypresses; and all the green and grey slopes sprinkled with villas which he can name as he looks at them. He sees other familiar objects much closer to his daily walks. For though he misses the seventy or more towers that once surrounded the walls and encircled the city as with a regal diadem, his eyes will not dwell on that blank; they are drawn irresistibly to the unique tower, springing like a tall flower-stem towards the sun, from the square turreted mass of the Old Palace, in the very heart of the city—the tower that looks none the worse for the four centuries that have passed since he used to walk under it. The great dome, too, greatest in the world, which, in his early boyhood, had been only a daring thought in the mind of a small, quick-eyed man—there it raises his large curves still, eclipsing the hills. And the well-known bell-towers—Giotto’s with its distant hint of rich colour, and the graceful spired Badia, and the rest—he looked at them all from the shoulder of his nurse.

“Surely,” he thinks, “Florence can still ring her bells with the solemn hammer-sound that used to beat on the hearts of her citizens and strike out the fire there. And here, on the right, stands the long dark mass of Santa Croce, where we buried our famous dead, laying the laurel on their cold brows, and fanning them with the breath of praise and of banners. But Santa Croce had no spire then: we Florentines were too full of great building projects to carry them all out in stone and marble; we had our frescoes and our shrines to pay for, not to speak of rapacious condottieri, bribed royalty, and purchased territories, and our façades and spires must needs wait. But what architect can the Frati Minori have employed to build that spire for them? If it had been built in my day, Filippo Brunelleschi or Michelozzo would have devised—something of another fashion than that—something worthy to crown the church of Arnolfo” … It is easier and pleasanter to recognise the old than to account for the new. And there flows Arno with its bridges just where they used to be—the Ponte Vecchio, least like other bridges in the world, laden with the same quaint shops, where our Spirit remembers lingering a little, on his way perhaps to look at the progress of that great palace which Messer Luca Pitti had set a-building with huge stones got from the hill of Bogoli close behind.

George Eliot, Romola, vol. 1, pp. 2–5.

S. Miniato may be approached from the Porta Romana by the enchanting drive Viale dei Colle, which winds with ever varying views under the lime-trees.

Monti superbi, la cui fronte Alpina

Fa da se contro i venti argine e sponda!

Valli beate, per cui d’onda in onda

L’Armo con passo signoril cammina!

Proud mountains, whose Alpine brow

Braces itself against the winds,

The river’s edge and shore!

From wave to wave, the Arno strides

With noble step through blessed valleys!

Vincenzo da Filicaia, “Nel Tornare dalla Villa di Figline a Firenze,” Poesia, p. 224.