5.2: From S. Trinità, Via Tornabuoni, Palazzo Davanzati

THE Piazza S. Trinità is, perhaps, the most central position in Florence, and near it are many of the principal hotels. Let us therefore take this as a starting-point for our various excursions over the city. It is situated at the S.W. corner of the site of the quadrangular Roman city, one side of which is represented by Via Tornabuoni, and another by Via Porta Rossa, both leading from this point.

The centre of the square is occupied by a column from the Baths of Caracalla at Rome, given to the Grand-Duke Cosimo I. by Pius IV. in 1564. It supports a porphyry statue of Justice, 1581, by Francesco Ferrucci. There is a pretty Florentine story that the figure is that of a beautiful girl, a servant in the opposite palace, who was executed for stealing a chain of pearls, which was found, years afterwards, in the scales of Justice, where it had been concealed by a jackdaw.

The neighbouring Church of S. Trinità, with a cinquecento façade and round window, dates in its foundation from the ninth, but was rebuilt in the thirteenth and entirely altered in the sixteenth century, and has quite recently been restored, and very well done by the late Prof. Castellazzi. The Mannerist façade is by Bernardo Buontalenti. Over the entrance is a relief of the Holy Trinity by Giov. Coccini. Entering the church, on the right of the central door is a marble shrine delicately sculptured with arabesques by Benedetto da Rovezzano, 1490–1550.

Nave, S. Trinità

The Gothic interior consists of a nave of five bays with double aisles and chapels; a transverse nave and a choir (with two chapels on either side of it), having a square instead of a round head to it. In general harmony of its features, and the dim religious light of it, despite a certain severity of style, this interior is perhaps the most pleasing of any in Florence. It now breathes again in its fourteenth century character. The ancient crypt is entered from the middle of the nave, through a wrought-iron grille, the original church having been much shorter. Over the crown of each arch of the nave is a coat of arms.

The 1st Chapel, right aisle (of the Della Stufa),contains a crucifix by Desiderio da Settignano, which was given to Florence by the Confraternita dei Bianchi. 3rd (R.). Pisani, Madonna and Saints by Neri dei Bicci. 4th (R.). Bartolini-Salimbeni has a rich XV.c. iron screen, and an Annunciation by Lorenzo Monaco, the Camaldolese friar.

The quiet grace and thoughtful character of the two happily placed figures has given a sort of typical value to this picture.

Jacob Burckhardt, Cicerone, p. 55.

5th (R.). Beautiful marble Altar by Benedetto da Rovezzano (1490–1550).

We now cross the transept to the 2nd Chapel (R.) of the Choir, named the Sassetti, from the monuments of Francesco Sassetti and Nera Cosi1Their portraits occur as donors on either side the altar., his lady, by Giuliano da San Gallo (1445–1516). But the chief attraction is the series of realistic frescoes by Domenico Ghirlandajo, representing scenes from the life of S. Francis (1485) in two sections. The best light in spring is about 10 A.M.

Upper Section, L.

(1) S. Francis banished from his father’s house, and casting himself at the feet of the Bishop of Assisi.

(2) Honorius III. confirms the Rule of the Order, depicted in the Piazza, della Signoria, and showing the Palazzo as it was in 1485. Among the capital portraits in this fresco is seen that of Lorenzo il Magnifico ascending the stairs.

(3) S. Francis before the Sultan in Syria, offering to pass through a fire in proof of Christian verity.

(4) He receives the Stigmata at La Vernia. The Convent is seen in the background.

(5) His death and funeral. The painter’s own portrait occurs here.

The fresco of the death of S. Francis is not only the most important and interesting of the series, but the one which, perhaps more than any other of his works, combines the highest qualities of Ghirlandajo as a fresco painter. The body of the dying Saint, wrapped in the coarse garment of his order, is stretched upon a bier. His disciples gather round him. One looks with an expression of most lively grief into the face of his expiring master. Others, kneeling, press his hands and feet to their lips with deep emotion. A citizen, in the dress of the painter’s time, opens the garment of the Saint, and places a finger on the miraculous wound in his side. Another, amazed at the sight of the “stigmata,” turns to a friar beside him. At the head of the bier stands a bishop, with spectacled nose, chanting the office for the dead. On either side of him is a priest, one bearing a censer, the other ready to sprinkle the corpse with holy water. At the other end of the bier are three acolytes, carrying a cross and lighted torches. Several citizens of Florence, also in the costume of Ghirlandajo’s day, appear as spectators. The one in a red head-dress immediately behind the bishop is the painter himself. The background consists of an apse with an altar, and an open colonnade of classic architecture, through which is seen a distant landscape of hill, plain, and river.

A.H. Layard, Domenico Ghirlandaio and His Fresco of the Death of S. Francis, pp. 16 & 19.

It is, of course, interesting to contrast the treatment of all these subjects with that of Giotto in S. Croce; and to note how great a change has come over Tuscan Art during the century and three-quarters elapsed.

(6) Above the altar S. Francis appears in a halo to restore to life a child of the Sassetti family killed by falling from a window. According to Vasari, the portraits here represent Maso degli Albizzi, Agnolo Acciajuoli, and Palla Strozzi. In the background occurs a view comprising the old Ponte Trinità, Palazzo Spini (now Ferroni), and the Church we are within.

On the vaulting are four Sybils. Above the High Altar is the celebrated Crucifix of S. Giovanni Gualberto (c. 985-1073), originally in San Miniato, and brought thence in great state (1671) by order of Duke Cosimo III. The Christ is related to have bowed the head on the day when San Giovanni pardoned his brother’s murderer. The Vallambrosians of this church influenced the Duke’s mind, and he granted their request.

The 1st Chapel to left of the Choir is that of the Usimbardi-Ficozzi, and contains the tomb of Paolo dell’ Abaco, the mathematician and poet (1282-1374), and those of two Bishops Usimbardi. The paintings are by Jacopo da Empoli (pupil of Del Sarto) and Giovanni da San Giovanni.

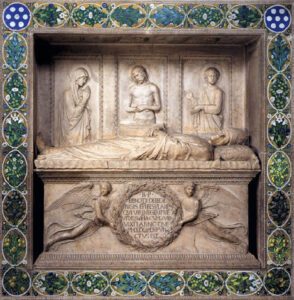

2nd Chapel left of Choir.—The beautiful tomb of Benozzo Federighi, Bishop of Fiesole, who died in 1450, is by Luca della Robbia. This monument was taken from the Church of S. Pancrazio to that of S. Francesco di Paola, whence it was brought here on the restoration of S. Trinità in 1896.

The admirably truthful figure of the dead bishop, clad in his episcopal robes, is laid upon a sarcophagus within a square recess, whose architrave and side-posts are decorated with enamelled tiles, painted with flowers and fruits coloured after nature. At the back of the recess, filling up the space above the sarcophagus, are three half-figures, of Christ, the Madonna, and S. John; all the faces are expressive, anzo Federihid that of the Saviour is especially fine, and full of mournful dignity. Around the top of the sarcophagus runs a rich cornice, below which are sculptured two flying angels, bearing between them a garland, containing an inscription setting forth the name and titles of the deceased.

Charles Perkins, Tuscan Sculptors, vol. 1, pp. 194–95.

Above is a half-length figure of Christ rising from the tomb with the Virgin and S. John on either side, and the whole is framed by a frieze of enamelled tiles, on which bouquets of lilies and roses, mingled with clusters of pears and medlars and fir-cones, are painted on a flat surface. “Cosa maravigliosa e rarissima!” [A marvellous and very rare thing!] exclaims Vasari, who says with truth that the hues of both fruit and flowers are as natural and brilliant as if they had been painted in oils.

Brit. Quart. Rev., Oct. 1885. [NOT IN OCT. 1885]

This monument is one of the most beautiful masterpieces of 15th century sepulchral sculpture, and it is understandable that Averulino, the most accredited didactic writer of this period, placed its author on the same level as Donatello.2Ce monument est un des plus beaux chefs-d’oeuvre de la sculpture sépulcrale du XVe siècle, et l’on comprend qu’Averulino, l’érivain didactique le plus accrédité de cette époque, ait placé son auteur sur la même ligne que Donatello. Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, p. 408.

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, vol. 1, p. 408.

1st Chapel, left aisle (Spini), contains the wonderful wooden statue of the Magdalen begun by Desiderio da Settignano and finished by Benedetto da Majano, formerly near the Façade. 2nd Chapel (Compagni) is the resting-place of the famous chronicler Dino Compagni. 3rd Chapel (Davanzati) has an ancient Christian sarcophagus, appropriated as the tomb of Giuliano Davanzati, 1444. The Annunciation over the altar is by Neri dei Bicci. 5th Chapel (Strozzi) has eighteenth century paintings by Poccetti.

The Sacristy was built by Palla Strozzi, who placed in it his father’s tomb. Some early relics are shown. On the ancient façade of the church was a mosaic representation of a pyx and consecrated wafer, commemorating a fight between the Guelfs and Ghibellines, in 1257, within the walls of the church, which was quelled by the priest bearing the sacrament, before which the armed foes first knelt to adore, and then rose in reconciliation.

Emerging from the Church, immediately to our right is the palace once occupied by the Gianfigliazzi3Arms of Gianfigliazzi: or, a lion rampant, azure., formerly a powerful Guelfic family, while opposite stands the massive embattled stronghold of the Spini4Arms of Spini: gules, a bend wavy, or. Arms of Ferroni: gules, a mailed arm bearing a sword, sable, and on a chief, azure, a lily, or. The Ferroni came from Empoli and were ennobled by Cosimo III. c. 1680. (now Ferroni palace), built in the XIII. c., a family illustrious from the foundation of Florence till it became extinct in 1686. The palace was once still more imposing, for in 1846 the municipality removed its fine tower, and an arch which spanned the Lung’ Arno, merely because they were inconvenient. There can be no doubt to this cruel curtailment is due the somewhat crude and gaunt effect of the edifice at the present day. Until recent years a large portion of it was occupied by the Library of G. P. Vieusseux,5Vieusseux died 1863, and had lived at No. 6 in the same Piazza Trinità at the Palazzo Buondelmonte. the founder of “L’Antologia” and the invaluable Archivio Storico, and a man of great intellectual and benevolent force of character. In 1938 Salvator Ferragamo purchased the Palazzo Spini-Ferroni and in 1995 a small museum featuring his shoes opened.

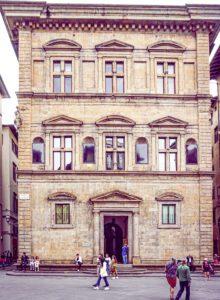

The palace opposite, formerly Bartolini-Salimbeni.6Arms of Bartolini: Gules, a lion rampant, argent, sable. (then Hôtel du Nord), was built from designs of Baccio d’Agnolo for the youngest of three brothers. One day, whilst they were dining, news was brought that a ship they had sent out had entered port, laden with precious treasures. Two of the brothers would not forego their midday siesta afterwards; the third went at once to secure the spoils: “Per non dormire,” [not to sleep] engraved over one of the doors inside the old house, commemorates this story.

Adjoining the Salimbeni is (No. 6) the Palazzo Buondelmonte, celebrated in Florentine story, though only built in the XV. c. on the site of the palace of the great family, so tragically famous in Church and State, which had its origin in brigand-chieftains—Buoni del Monte—men of the mountain who came from the castle of Montebuoni, and descends from Sichelmo, whose great-grandson, Giovanni Gualberto, founded the Vallombrosan order.7Arms Vallombrosan Order: Argent, in chief a cross gules, above three or seven monti azure. In the older palace lived, in 1218, the handsome young Buondelmonte who deserted the Amidei bride to whom he was betrothed, for love of Fina Donati, and was murdered on his wedding-day by the Lamberteschi (1215) while he was crossing the Ponte Vecchio. In 1838 Tsar Alexander I. and Prince Metternich were lodged at the Palazzo Buondelmonte in the suite on the first floor decorated with paintings by Poccetti.

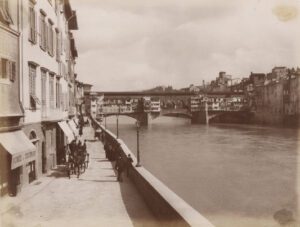

The houses, which rise out of the Arno, bright with soft tints of colour, irregular, picturesque, various, with roofs at every possible elevation, the one sole point necessary being, that no two should have the same level—the outline broken with loggias, balconies, projecting lines, quaint cupolas, and spires; the stream flowing full below, reflecting every salient point, every window on the high perpendicular line, every cloud on the blue overarching sky;—this fair conjunction gives, at the first glance, that gleam of colour, light, sunshine, and warmth which is conventionally necessary to an Italian town.

“Two Cities—Two Books,” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, p. 74.

If we now turn to the left, and ascend the bank of the river by Lung’ Arno Acciaiuoli8Arms of Acciajuoli: Argent, a lion, erect, azure. (named from Houses of the powerful family which produced Niccolò Acciaiuoli, the favourite of King Robert of Naples, and the Via Archibusieri, passing the Ponte Vecchio, we shall soon meet the end of the stately porticoes of the Uffizi.

Belted with its many bridges, and margined with towers and palaces, Arno is the most beautiful and stately thing in the beautiful and stately city, whether it is in a dramatic passion from the recent rains, or dreamily raving of summer drouth over its dam, and stretching a bar of silver from shore to shore.

D. Howells, Tuscan Cities, pp. 138–139.

Oh, that Arno in the sunset, with the moon and evening star standing by, how divine it is!

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Letters, vol. 1, p. 373.

The first open staircase on the east, or right, formerly led to the National Library,9Since 1935 the National Library of Florence (Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze) has been located in a building designed by Cesare Bazzini and V. Mazzei. The collections were damaged when the Arno flooded in 1966. occupying what was once the first Florentine Theatre. Here was first performed the “Armida” of Tasso, who rode from Ferrara to express his gratitude to Buontalenti, the designer of its scenes. The Library contains about 200,000 printed volumes and 14,000 MSS. That part of it which is called the Magliabecchiana Library was begun in the seventeenth century by a poor man named Antonio Magliabecchi (1633–1714), whose talents drew the attention of Cosimo III., by whom he was made librarian. He had been shop-boy to a jeweller in Ponte Vecchio, and later lived in the Piazza S. Maria Novella in the utmost discomfort among his books. His immense learning caused Mabillon to write of him as “Ipse museum inambulans, et viva quaedam bibliotheca..” [He’s walking into a museum, and living in a library.] His whole life was one of the utmost parsimony for the sake of collecting books, and he died in the Infirmary of S. Maria Novella, bequeathing his library to the city of Florence. It has since been greatly increased, and was united to the Palatine Library in 1864.

The halls of the Library are remarkable as having witnessed the meetings of two famous literary societies; the Accademia della Crusca, founded by Cosimo I., in order to improve the Italian language by separating the wheat from the bran—whence the name, from crusca, bran;10The Accademia della Crusca still meets in the Convent of S. Marco. and the Accademia del Pimento, founded by Ferdinand II. in 1657, with the object of testing all discoveries by experiments. This society lasted for only twenty years. The Library includes 300 volumes of letters and papers of Galileo and his contemporaries (amongst them a letter of Vincenzo Viviani, proving that Galileo was the first to apply the pendulum to a clock); the Bible of Savonarola, with his written comments on the margin, and his breviary with an inscription by his pupil Fra Serafino; the letters of Benvenuto Cellini (one describing the death of his child); a sketch-book of Lorenzo Ghiberti; a missal said to have belonged to the Emperor Otho III. (983–1002); some letters of Benvenuto Cellini, a Dante of 1481, and an invaluable collection of MS. music, and of the Elzevir, Aldi and Bodoni editions. The library is open to the public daily except on feast days. On the upper floor were the Archives of Tuscany.11After the flood of 1966, it was decided to build a modern building to house the Archives removed from the river. In 1974 construction began on the new building, designed by Italo Gamberini and located on the Viale della Giovane Italia. The second great entrance of the Uffizi leads to the renowned Gallery on the second floor originally founded by Francesco I., with the relics of the treasures accumulated by his Medicean ancestors, and splendidly enriched by his successors, especially the Electress-Palatine, sister of Gian-Gastone.