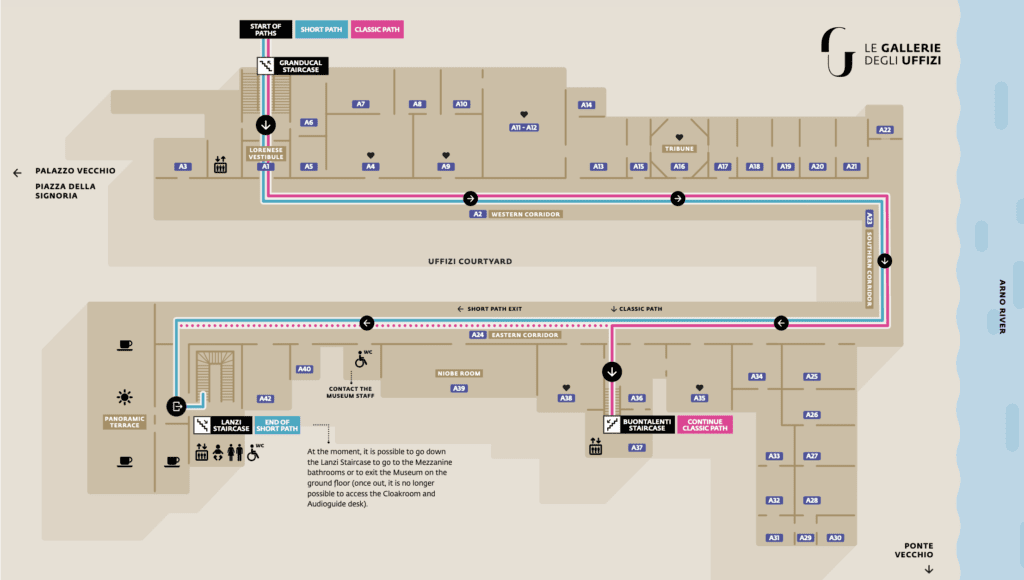

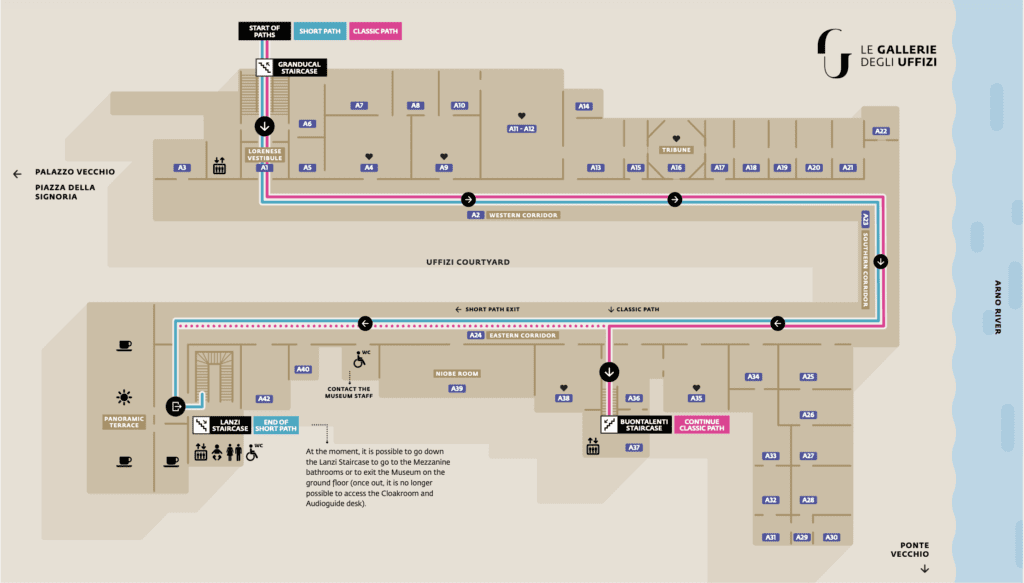

2nd Floor Plan (photo credit Le Gallerie degli Uffizi)

3.2A: Uffizi Galleries, 2nd Floor

One of the great museums of the West whose peers include the National Gallery (London), Louvre (Paris), Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), and the National Gallery of Art (Washington), the Uffizi Galleries—since 2016 officially the Galleria delle Statue e delle Pitture—house the world’s most important collection of Italian Renaissance art. The name change seeks to highlight anew the sculpture collection, which was once the great glory of the museum, but which has taken second place to the paintings. In 2021 the Uffizi Galleria delle Statue e delle Pitture saw almost one million visitors, most of whom it seemed arriving on the very day of my last visit. Thus it is important to plan ones visit, make advance reservations, and recognize that it is impossible “to do” the Uffizi in a single visit. Nonetheless, the better prepared one is, the more one will gain from their visit.

A brief history of the Uffizi:

Desiring a new palace to house various government offices (uffizi), Cosimo I. (1519–1574) commissioned Giorgio Vasari to build a magnificent, Doric-order edifice as an annex to the Palazzo Vecchio. Work commenced in 1560 and was continued after Vasari’s death in 1574 by Alfonso Parigi and Bernardo Buontalenti who closely followed the former’s original plans. Completed in 1580, the u-shaped building consists of two long parallel wings and a shorter one on the south side facing the Arno River. They enclose a narrow square bounded by the stately porticoes of the Uffizi. Between the arches which open toward the Arno stand statues of the Florentine heroes, Francesco Ferrucci, Giovanni delle Bande Nere, and Farinata degli Uberti. The pillars of the colonnades are adorned with statues of the great Florentine sculptors, painters, poets, historians, and other eminent citizens. The best is that (fifth on left) of the Archbishop S. Antoninio, the good Dominican chronicler, by Dupré. At the extremity of the arcade on the left the late Post Office occupied the site of the ancient Zecca, or mint.

Cosimo’s son, Francesco I. (1541–1587) ordered Bernardo Buontalenti to enclose the open loggia on the upper floor of the east wing and to create a long corridor to display sculpture and galleries to house paintings. In 1584 Buontalenti constructed the Tribune. When Francesco died under mysterious circumstances in 1587, his younger brother Ferdinando (1549–1609), then a cardinal, gave up his red hat and became Grand Duke of Tuscany. As Ferdinando I., he transferred many excellent works, especially antiquities, from his Roman villa to Florence. In 1609, after a reign of 22 years, Ferdinando was succeeded by his son Cosimo II. (1590–1621). Ferdinando II. (1610–1670) enclosed the southern and western loggie to accommodate his ever-growing collection, which was greatly enhanced when he married Vittoria delle Rovere of Urbino. Among the many important paintings by Raffaello and Piero della Francesca that she added to the collection was Titian’s Venus of Urbino. With Cosimo III. (1642–1733), further masterpieces from the Villa Medici in Rome including the Venus de’ Medici, the Knife Grinder, and the Wrestlers found a home in the Tribune. Giovanni Gastone (1671–1737), son of Cosimo III. died childless. His sister Anna Maria Luisa (1667–1743), Electress Palatine, inherited the entire Medici collection, which she bequeathed to the People of Florence. In addition, she added excellent works by Northern European artists from her own collection. Her sole stipulation was that her gift never leave Florence.

With the end of the Medici line, the Grand Dukedom of Tuscany passed to the House of Lorraine. Francesco II. (1708–1765) added to the collection and Leopoldo I. (1747–1792) furthered the Portraits of Painters collection, gathered together all remaining portable artworks belonging to Medici family members, and installed many of them in the renovated west corridor and adjoining rooms. Most significantly Leopoldo decreed that the Uffizi Galleries be open daily to the public. The Uffizi is the oldest museum of the modern era.

In the early 19th century during the reign of Ferdinando III. (1769–1824), the French invaded Italy. On Napoleon’s orders, the Venus de’ Medici and many of the finest paintings were taken to Paris. After the fall of Napoleon, some but not all of the looted masterpieces were returned to Florence.

In the 19th century, numerous paintings were removed from Florentine churches to the Uffizi. Renaissance sculptural masterpieces, including works by Donatello, Luca della Robbia, Benvenuto Cellini, and others, were transferred to the Bargello. The Egyptian treasures went to the Archaeological Museum. In the 20th century, the State Archives were moved to a new location. This freed up space on the 1st floor and has allowed for a significant expansion of gallery space. On May 27, 1993, the Sicilian Mafia exploded a powerful car bomb near the Uffizi causing the loss of 5 lives and damaging the SW corner of the building.

Beginning in the 1990s, the Uffizi Galleries have undergone extensive remodeling, renovations, and reinstallations of artworks as part of a “Nuovo Uffizi” master plan. State-of-the-art cocoons now regulate environmental conditions, including temperature and humidity, for many of the most iconic paintings in the collection. Other paintings are glazed to protect them from accidental and/or willful damage. New galleries on the first floor were created and numerous works long in storage are now on view. One measure of this expansion is that the 6th edition of Hare’s Florence (1904) noted 20 halls or rooms and the 9th edition (1925) counted 32; currently the number of galleries is approaching 100. The galleries have been renumbered: currently those on the second floor are numbered A1-A42; those on the first floor are numbered D1-D35 and C1-C14, the Cardinal Leopoldo de’Medici Room of Artists’ self-portraits. Additional galleries will be added in the future.

In addition, public outreach via the internet has increased dramatically since the Uffizi website was launched, somewhat belatedly, in 2015. Efforts to become more contemporary have increased, or as former Director Eike Schmidt observed: “For me, it has been very important to get the dust off, and to show what is relevant.” According to the New York Times (Jan. 31, 2022), Schmidt has sought “to integrate more contemporary art, to increase the presence of female artists and artists of color and to reach a younger, more diverse audience.” Not all traditionalists agree with this very 21st-century vision.

The famous Vasari Corridor is undergoing updating and is scheduled to reopen in 2023. Built by Vasari in 6 short months in 1565, the Corridor links the Uffizi and the Pitti Palace, where Cosimo I. had taken up residence after Eleonora of Toledo, his wife, purchased the property from the Pitti. Some claim that the Corridor was built in imitation of the passage which Homer describes as uniting the palace of Hector to that of Priam. Approximately 1 kilometer in length, the Corridor provided a secure and discrete route for the Grand Duke to traverse between his residence and the offices of the State. The Corridor crosses the Arno above the Ponte Vecchio shops before turning sharply east, entering the Uffizi on the 2nd floor. The Corridor contains a famous collection of artists’ self-portraits begun by Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici (1617–1675), the son of Cosimo II.

We enter the Uffizi from the ground floor through either Door 1 or 2 on the east side of the Uffizi Courtyard and proceed to the Grand Ducal staircase that leads to the renowned Gallery on the second floor originally founded by Francesco I., with the relics of the treasures accumulated by his Medicean ancestors, and splendidly enriched by his successors, especially the Electress-Palatine, sister of Gian-Gastone. According to the newest arrangement of the Gallery all of the rooms are numbered, and many new ones have been added. One excellent result of this new distribution is that the most important masterpieces of the Italian schools, both Tuscan and Umbrian, have been gathered together and grouped in rooms opening out of the 1st (East) Corridor. The drawings, formerly exposed in cases along the corridors, are now very properly preserved from the light in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe on the first floor (Admission by appointment only).

Uffizi Gallery, 2nd Floor (Courtesy Le Gallerie degli Uffizi)

XIII – XIV CENTURY

A1 Lorenese

Vestibule

A2 East Corridor

A3 Medieval painting

A4 Giotto – Cimabue

A5 Lorenzetti –

Simone Martini

A6 14th Century

A7 Lorenzo Monaco,

Gentile da Fabriano

EARLY RENAISSANCE

A8 Masaccio –

Beato Angelico

A9 P. Uccello,

F. Lippi,

Piero della Francesca

A10 I Pollaiolo

A11 Botticelli The Spring

A12 Botticelli Venus

A13 Hugo van der Goes

A14 The Uffizi’s Maps Terrace

A15 Room of Mathematics

RENAISSANCE OUTSIDE FLORENCE

A17 15th Century in Siena

A18 Mantegna, Bellini,

Antonello da Messina

A19 15th Century in Veneto

A20 15th Century in Emilia Romagna

A21 15th Century in Lombardia

A22 Bouvoir of Miniatures

HIGH RENAISSANCE

A25 Domenico Ghirlandaio

A26 Cosimo Rosselli

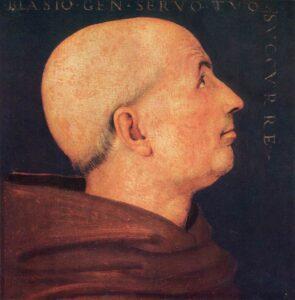

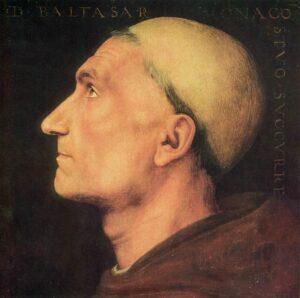

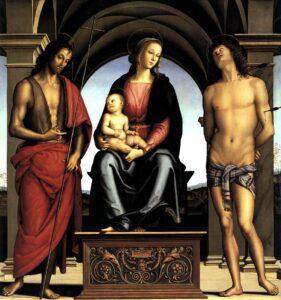

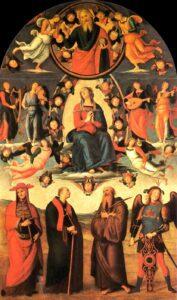

A27 Pietro Perugino

A28 Filippino Lippi, Piero di Cosimo

A29 Lorenzo di Credi

A30 Doryphoros

A31 Luca Signorelli

A32 Luca Signorelli

A33 Greek portrait sculptures

A34 The antique and the Garden

of San Marco

A35 Leonardo Da Vinci

A36 Hall of Ancient Inscriptions

A38 Raphael and Michelangelo

A39 Niobe Room

A40 Hermaphrodite

A42 Dürer and the transalpine Renaissance

Reaching the second floor, we enter (see Plan) the Vestibules. In the 1st Vestibule are interesting portrait-busts of the Medici and Lorraine Dukes, to whom we owe the collection. They present curious phases of transition from Lorenzo and Cosimo I. to Gian Gastone. Good looks are scarce with them!

In the Lorraine Vestibule (circular) are two Molossian Hounds, two sarcophagai, and two statues: one is a 2nd c. Apollo, and the other is Trajan. Hence we enter the 1st (East) Corridor, painted with arabesques in 1581 by B. Poccetti. Among the art treasures here are a series of Busts of Roman Emperors, only surpassed by those at the Capitol and at Naples. Few of the statues are either originals or first-rate, and, as usual, restoration has been made ignorantly.

Among these latter busts we count by scores

Half Emperors and quarter Emperors,

Each with his bay-leaf fillet, loose thonged vest,

Loric and low-browed Gorgon on the breast,

One loves a baby face, with violets there,

Violets instead of laurel in the hair,

As those were all the little locks could bear.

Robert Browning, Protus.

1st (East) Corridor:

Left. Antonia.

Athlete with a vase. Arms restored.

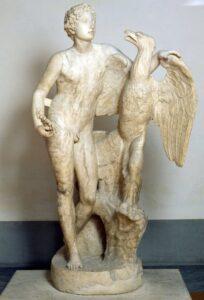

Right. Ganymede. Head and arms modern.

A statue of surpassing beauty. One of the eagle’s wings is half enfolded round him, and one of his arms is placed round the eagle, and his delicate hand lightly touches the wing; the other holds what I imagine to be a representation of the thunder. These hands and fingers are so delicate and light that it seems as if the spirit of pleasure, of light, life, and beauty, that lives in. them, had lifted them and deprived them of the natural weight of the mortal flesh. The roundness and fulness of the flowing perfection of his form is strange and rare. The attitude and form of the legs, and the relation borne to each other by his light and delicate feet, are peculiarly beautiful. The calves of the legs almost touching each other, one foot is placed on the ground a little advanced before the other, which is raised, the knee being a little bent, as those who are slightly, but slightly, fatigued with standing. The face, though innocent and pretty, has no ideal beauty. It expresses [inexperience and gentleness and innocent wonder, such as might be imagined in a rude and lovely shepherd-boy and no more.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Ganymede,” Prose Works, vol. 3, pp. 64–65.

2nd Corridor:

Roman Lady seated; head modern; body ancient.

Roman Lady seated; body iv c. Greek. Head of Agrippina (?).

Pallas, with a Scopasian head. Head and body belong to two different statues.

Her face uplifted to heaven is animated with a profound, sweet, and impassioned melancholy, with an earnest, fervid, and disinterested pleading against some vast and inevitable wrong; it is the joy and the poetry of sorrow, making grief beautiful, and giving to that nameless feeling which from the imperfection of language we call pain, but which is not all pain, those feelings which make not only the possessor but the spectator of it prefer it to what is called pleasure, in which all is not pleasure.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, “A Statue of Minerva,” Prose Works, vol. 3, pp. 61–62.

Sarcophagus with the story of Phaethon; and a Race in the Circus, with names of the drivers.

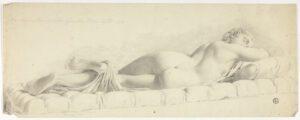

Venus Anadyomene. Head restored and left leg modern.

Dinanzi a noi pareva si verace

Che non sembiava imagine che tace.

There sculptured in a gracious attitude,

He did not seem an image that is silent.

Dante Purgatorio 10:37&39. Trans. Longfellow.

She seems to have just issued from the bath, and yet to be animated with the enjoyment of it. She seems all soft and mild enjoyment, and the curved lines of her fine limbs flow into each other with never-ending continuity of sweetness. Her face expresses a breathless yet passive and innocent voluptuousness without affectation, without doubt; it is at once desire and enjoyment and the pleasure arising from both. . . . Her form is indeed perfect. She is half sitting on and half rising from a shell, and the fulness of her limbs, and their complete roundness and perfection, do not diminish the vital energy with which they seem to be imbued. The attitude of her arms, which are lovely beyond imagination, is natural, unaffected, and unforced. This perhaps is the finest personification of Venus, the Deity of superficial desire, in all antique statuary.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Venus Anadyomene,” Prose Works, vol. 3, pp. 59–61.

Room A3 Early Tuscan Painters

Credette Cimabue ne la pittura

sì che la fama di colui è scura

tener lo campo, e ora ha Giotto il grido,

In painting Cimabue thought that he

Should hold the field, now Giotto has the cry,

So that the other’s fame is growing dim.

Dante Purgatorio 11:94-96, Trans. Longfellow.

Giotto, had so excellent a genius that there was nothing of all which Nature, mother and mover of all things, presenteth unto us by the ceaseless revolution of the heavens, but he with pencil and pen and brush depicted it and that so closely that not like, nay, but rather the thing itself it seemed, insomuch that men’s visual sense is found to have been oftentimes deceived in things of his fashion, taking that for real which was but depictured. Wherefore, he having brought back to the light this art, which had for many an age lain buried under the errors of certain folk, who painted more to divert the eyes of the ignorant than to please the understanding of the judicious, he may deservedly be styled one ofthe chief glories of Florence, the more so that he bore the honors he had gained with the utmost humility and although, while he lived, chief over all else in his art, he still refused to be called master, which title, though rejected by him, shone so much the more gloriously in him as it was with greater eagerness greedily usurped by those who knew less than he, or by his disciples.

Boccaccio, Decameron, Trans. J.M. Rigg, vol.2, p. 43.

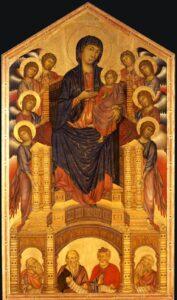

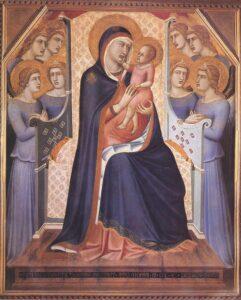

You will gaze on it with interest, if not with admiration, for, independently of pictorial merit, it is linked with history. Charles of Anjou, King of Naples, passing through Florence while he was engaged in painting it, was taken to see it at the artist’s bogetta or studio, as it would now be termed, outside the Porta S. Piero. Rumour had been busy, but no one had as yet obtained a glimpse of it—all Florence crowded in after him—nothing like it had till then been seen in Tuscany, and, when finished, it was carried in solemn procession to the church, followed by the whole population, and with such triumphs and rejoicings that the quarter where the painter dwelt obtained the name, which it has ever since retained, of Borgo Allegri.1This was the subject of the picture which first made the fame of Sir Frederick Leighton. Nor can I think that this enthusiasm was solely excited by a comparative superiority to contemporary art; it has a character of its own, and, once seen, stands out from the crowd of Madonnas, individual and distinct. The type is still the Byzantine, intellectualised perhaps, yet neither beautiful nor graceful, but there is a dignity and a majesty in her mien, and an expression of inward pondering and sad anticipation rising from her heart to her eyes as they meet yours, which one cannot forget. The Child too, blessing with its right hand, is full of the Deity, and the first object in the picture, a propriety seldom lost sight of by the older Christian painters. And the attendant angels, though as like as twins, have much grace and sweetness.

Lord Lindsay, Christian Art, vol. 1, p. 344.

Ascend the right stair from the farther nave2At the time the painting was given to Cimabue and was located in the Rucellai Chapel, Santa Maria Novella. To muse in a small chapel scarcely lit By Cimabue’s Virgin. Bright and brave That picture was accounted, mark, of old. A king stood bare before its sovran grace, A reverent people shouted to behold The picture, not the king, and even the place Containing such a miracle grew bold, Named the glad Borgo from that beauteous face Which thrilled the artist, after work, to think His own ideal Mary-smile should stand So very near him,—he, within the brink Of all that glory, let in by his hand With too divine a rashness! Yet none shrink Who come to gaze here now; albeit ’twas planned Sublimely in the thought’s simplicity: The Lady, throned in empyreal state, Minds only the young Babe upon her knee, While sidelong angels bear the royal weight, Prostrated meekly, smiling tenderly Oblivion of their wings; the Child thereat Stretching its hand like God. If any should, Because of some stiff draperies and loose joints, Gaze scorn down from the heights of Raphaelhood On Cimabue’s picture,—Heaven anoints The head of no such critic, and his blood The poet’s curse strikes full on and appoints To ague and cold spasms for evermore. A noble picture! worthy of the shout Wherewith along the streets the people bore Its cherub-faces, which the sun threw out, Until they stooped and entered the church door.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Casa Guidi Windows, Part 1:10.

I could see no charm whatever in the broad-faced Virgin, and it would relieve my mind and rejoice my spirit if the picture were borne out of the church in another triumphal procession (like the one which brought it there) and reverently burnt.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, Passages from the French and Italian Note-Books, vol. 2, p. 95.

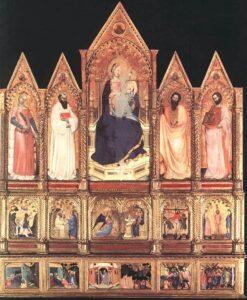

Pietro Lorenzetti (documented from 1306 to 1348), Saint Humility and Scenes from Her Life, 1335-c. 1340

This pathetic scene was treated on several occasions, and always with love, by Giotto and by his disciples; but neither did he ever succeed in realizing to this point the manifestation of a pain the depth of which is not given to any created mind to measure. What silent eloquence in those bloody nails, shown by one of the assistants and since imitated by Fra Angelico! What a style of drapery, and what a color full of harmony and vigor!

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, pp. 234–35.

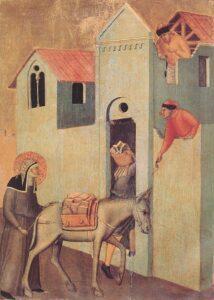

Room A7 Lorenzo Monaco, Gentile da Fabriano

Gentile da Fabiano. The Adoration of the Magi, 1423. In the Predella, the Nativity and the Flight into Egypt a curious and important picture. The crudely foreshortened horses, camels, birds, and dogs, recall Paolo Uccello. From the Sacristy of S. Trinità.

This masterpiece, in default of any other by Gentile, would suffice in itself to explain the eagerness with which the products of his brush were sought from one end of Italy to the other. Since the beginning of the 15th century, we can say, with truth, that nothing comparable to this painting had been seen.

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, vol. 2, p. 8.

Masolino (Tommaso di Cristofano Fini), Madonna of Humility, c. 1415

Masaccio (Tommaso di ser Giovanni, 1401 – 1428), Saint Anne, Madonna and Child, Five Angels (called Sant’Anna Metterza), c. 1424

But superior to all the other works of Fra Giovanni, and one in which he surpassed himself, is … the Coronation of the Virgin by Jesus Christ: the principal figures are surrounded by a choir of angels, among whom are vast numbers of saints and holy personages, male and female. These figures are so numerous, so well executed, in attitudes so varied, and with expressions of the head so richly diversified, that one feels infinite pleasure and delight in regarding them. Nay, one is convinced that those blessed spirits can look no otherwise in heaven itself, or, to speak under correction, could not, if they had forms, appear otherwise; for all the saints, male and female, assembled here, have not only life and expression, most delicately and truly rendered, but the colouring also of the whole work would seem to have been given by the hand of a saint, or of an angel like themselves.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 2, p. 37.

Quite unearthly is the Coronation of the Virgin: the Madonna, crossing her hands meekly on her bosom and bending in humble awe to receive the crown of heaven, is very lovely the Saviour is perhaps a shade less excellent; the angels are admirable, and many of the assistant saints full of grace and dignity; but the characteristic of the picture is the flood of radiance and glory diffused over it, the brightest colours gold, azure, pink, red, yellow pure and unmixed, yet harmonising and blending, like a rich burst of wind-music, in a manner incommunicable in recital distinct and yet soft, as if the whole scene were mirrored in the sea of glass that burns before the throne.

Lord Lindsay, Christian Art, vol. 2, pp. 234–35.

Domenico Veneziano (1410-1461), fabled to have been murdered by the jealousy of Andrea del Castagno,3A document has been discovered which proves that the supposed murderer died before his supposed victim, namely, May 15, 1461. but interesting as being the master of Piero della Francesca, whom he brought to Florence as his pupil in 1439. This, the altar-piece of S. Lucia de’Bardi, is his one extant picture.

It bespeaks a painter whose conceptions are governed by those of Andrea del Castagno, while in technical processes he is working out experiments of his own. The Saints, John and Nicholas, and Francis and Lucy, especially the John, have strong figures and large dull heads, and that commonness with athletic vigour which marks the thorough-going realist. But the medium is new. It is a first commencement of oil-painting, and the search for the transparent effects produces a result quite different from any contemporary colouring a scheme of light and thin greys, greens, blues, and pinks, with notes of sharp black and white on the marbles of the floor and canopy; gaiety and transparency are attained, but not harmony.

S. C. [St. Clair Baddeley]

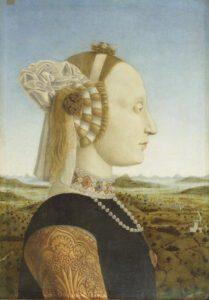

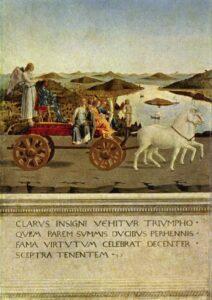

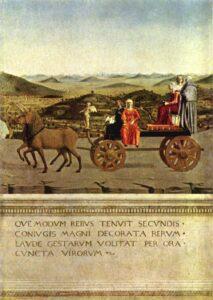

Piero della Francesca (1416/17 – 1492), Portraits of Federigo di Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino and his wife, Battista Sforza, c. 1473-1475. These masterly portraits are most interesting to those who have visited the great works at Urbino. At the back of each is a triumph, Federigo seated in a car drawn by white horses, Battista in one drawn by dun-coloured unicorns.

In the Duchess one notices once more the ovoidal head of the Queen of Sheba in the frescoes at Arezzo, as well as its simplicity of expression: merely differing in possessing a higher forehead, less arched eyebrows, the nose rather sharper, and the lips rather more subtle in expression. The two figures stand out in severe profile against a riverine landscape, and with a golden simplicity, and, indeed, a homeliness, which one does not find in portraits of a later age. On the reverse of each picture is depicted their triumph; seated upon a chariot drawn by unicorns, guided by Cupid, and adorned by the Virtues, Bianca reads a little book of gold. Federigo in glittering steel is seated on a similar chariot, drawn by white horses, while Victoria crowns him.

Adolfo Venturi, Storia dell’ Arte Italiana, vol. 7, pt. 1, Milano: Ulrico Hoepli, 1901, p. 466.

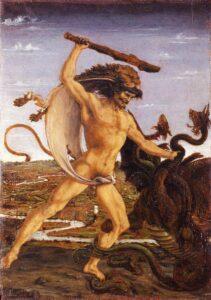

[I]n the Medici Palace he painted three pictures for Lorenzo the elder, each containing a figure of Hercules, five braccia high. In the first is seen the hero strangling Antæus, the figure of Hercules is very fine, and the force employed by him in crushing his antagonist is clearly apparent, every muscle and nerve of the body being strained to ensure the destruction of his opponent. The teeth, firmly set, are in perfect accord with the expression of the other parts of the figure, all of which, even to the points of the feet on which he raises himself, give manifest intimation of the efforts used. Nor is less care displayed in the figure of Antæus, who, pressed by the arms of Hercules, is seen to be sinking and deprived of all power of resistance, his mouth is open, he is breathing his last sigh….The third picture, in which the hero is destroying the Hydra, is indeed an admirable work, more especially as regards the reptile, the colouring of which has so much animation and truth, that nothing more life-like could possibly be seen; the venomous nature, the fire, the ferocity, and the rage of the monster are so effectually displayed, that the master merits the highest encomiums, and deserves to be imitated in this respect by all good artists.4These paintings are copies on a smaller scale. The 5 braccia high originals (approximately 11.5 feet high) owned by Lorenzo and described by Vasari, no longer exist.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 2, pp. 199–200.

Rooms A11-A12

Sandro Botticelli (1445 -1510), Primavera. An allegory of Spring, with the three Graces, and Venus scattering flowers—a very interesting picture, painted for the villa of Cosimo de’ Medici at Castello. Giuliano de’ Medici is presented as Mercury. The painter also has had in his mind the Judgment of Paris. Painted in honour of “la bella Simonetta” before her decease.

The scene is a landscape of wood, orchard, and flowery meadow. A man with a winged helmet like a Mercury, scantily draped about the hips with a sword at his side, and striking down fruit from a tree, offers to the spectator a youthful form in fair movement and proportion. Three females near him (the Graces?) dance on the green sward in the light folds of transparent veils; a fourth (Venus?) stands in rich attire in the centre of the ground, whilst, above them, the blind Cupid flies down with his lighted torch. On the right a flying genius, whose dress flutters in the wind, wafts a stream of air towards a female, in whose hand is a bow and from whose mouth sprigs of roses fall into the garment of a nymph at her side.

Crowe and Cavalcaselle, New History of Painting in Italy, vol. 2, p. 418.

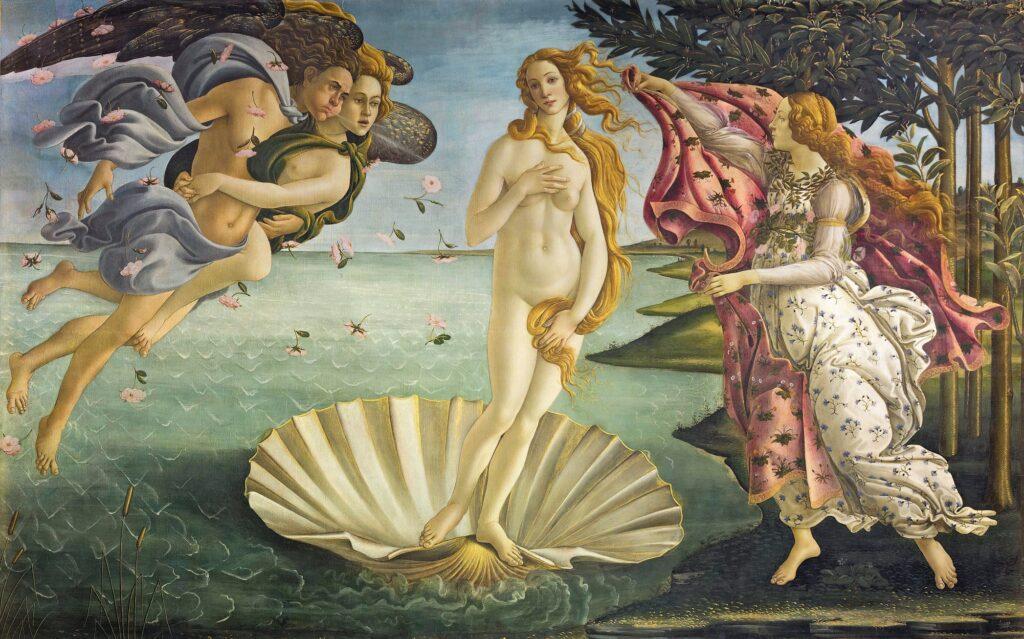

Like the “Spring,” [the Birth; of Venus ] was painted, but at a later time, for the decoration of Castello, the villa of Lorenzo and Giovanni, the sons of Pierfrancesco de’ Medici….The Goddess, amid a shower of roses, stands naked in the little bark; of the shell, in the attitude of the Medicean Venus. On the left of the picture, two winged zephyrs ” blow hard across the gray water, moving forward the dainty-lipped shell on which she sails; the sea ‘showing his teeth’ on thin lines of foam, and sucking in one by one the falling roses, each severe in outline, plucked off short at the stalk, but embrowned a little, as Botticelli’s roses always are.” On the other side, a nymph in an ample dress of white, powdered with sprigs of corn-cockle, having a wreath of myrtle about the neck, and girdled about the waist with rose-branches, steps forward on the shore, ready to cast a purple cloak, sprinkled with knots of daisies;, about the naked goddess, as soon as she shall step to land. The orange trees are in flower; and along the water’s edge, the distant shore juts out into little promontories in the clear morning air.

Herbert P. Horne, Sandro Botticelli, Painter of Florence, p. 148.

For this picture Sandro studied, and produced not only a really beautiful nude, but a charming fairylike impression, which unconsciously takes the place of the mythological one.

Jacob Burckhardt, Cicerone, p. 62.

The lines of gold are exquisitely laid on: they are as stately and rhythmical as lines from the burin of Mantegna.

Charles Holroyd. “Notes on Various Works of Art: Florence Revisited,” p. 227.

Calumny of Apelles, painted by Sandro Botticelli after his absence at Rome (during which his enemies had accused him of heresy), and presented to his friend Messer Antonio Segni, a Florentine gentleman, for whom Leonardo designed a Neptune. For inspiration, Botticelli turned to the essay on “Slander” by Lucian of Samosata (born c. 125 CE) in which Apelles takes revenge on Antiphilus, a rival painter, with a painting that is described in detail:

Apelles, for his part, mindful of the risk that he had run, hit back at slander in a painting. On the right of it sits a man with very large ears, almost like those of Midas, extending his hand to Slander while she is still at some distance from him. Near him, on one side, stand two women—Ignorance, I think, and Suspicion. On the other side, Slander is coming up, a woman beautiful beyond measure, but full of passion and excitement, evincing as she does fury and wrath by carrying in her left hand a blazing torch and with the other dragging by the hair a young man who stretches out his hands to heaven and calls the gods to witness his innocence. She is conducted by a pale ugly man who has a piercing eye and looks as if he had wasted away in long illness; he may be supposed to be Envy. Besides, there are two women in attendance on Slander, egging her on, tiring her and tricking her out. According to the interpretation of them given me by the guide to the picture, one was Treachery and the other Deceit. They were followed by a woman dressed in deep mourning, with black clothes all in tatters—Repentance, I think, her name was. At all events, she was turning back with tears in her eyes and casting a stealthy glance, full of shame, at Truth, who was approaching.

Lucian of Samosata, Lucian, Trans. A. M. Harmon, vol. 1, London: W. Heinemann, 1913, pp. 365 & 367.

Then comes Penitence, old, and wrapped in a dark mantle, one hand grasping at the other beneath it, and turning her attentive head to regard Truth, nude and beautiful. The details in the rich reliefs of the architecture are composed in artistic harmony with the main theme. There are seen: a Centaur being dragged by an angry Goddess; Cupid shooting at a prison; sleeping Nymphs, Fauns and Centaurs, and Athletes. And with the mythological motives are mixed biblical ones, notably Judith carrying the head of Holofernes.

Adolfo Venturi, Storia dell’ Arte Italiana.

This is the masterpiece of the artist in the representation of allegory, as well as the choicest specimen of his passionate poetry. Few painters have succeeded in making every part of a work so tributary to the leading idea: the very statues in the niches are enlisted in the service. Such a picture as this is a far juster revelation of the violence and fiery spirit predominant at Florence than any which the literature of the time has bequeathed.

Franz Theodor Kugler, Handbook of Painting, vol. 1, p. 230.

Similar in size to that of the Magi just mentioned is a picture, now in the possession of the Florentine noble, Messer Fabio Segni. The subject of this work is the Calumny of Apelles, and nothing more perfectly depicted could be imagined. Beneath this picture, which was presented by Sandro himself to Antonio Segni, his most intimate friend, are now to be read the following verses, written by the above-named Messer Fabio:—

Indicio quemquam ne falso laedere tentent

Terrarum reges, parva tabella monet

Huic similem AEgypti regi donavit Apelles:

Rex fuit et dignus munere, munus eo.

A small tablet warns the earthly kings

not to harm anyone with falsehoods.

Apelles gave a similar gift to the Egyptian king:

He was a king, and worthy of his office.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 2, pp. 222–23.

Room A13 Hugo van der Goes (c. 1440 –1482)

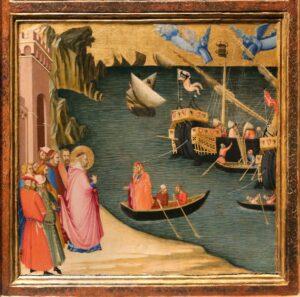

Hugo van der Goes, “The Portinari Altarpiece,” Adoration of the Shepherds with angels and Saint Thomas, Saint Anthony, Saint Margaret, Mary Magdalen and the Portinari family (recto); Annunciation (verso), 1477-c. 78. Tommaso Portinari, a long-time Medici banker resident in Bruges, commissioned the painting for the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, which had been founded by Folco Portinari, an ancestor, in 1285.

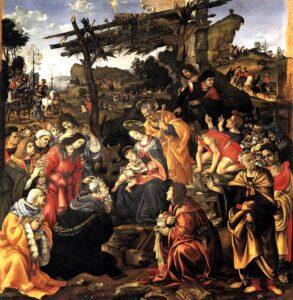

Sandro Botticelli, The Adoration of the Magi, a deeply interesting picture, full of power and expression. This picture was painted for S. Maria Novella, perhaps c. 1478. The painter has placed the scene among the remains of a classical ruin covered by a timbered roof, from the centre of which the divine star showers its benignant light upon the Virgin, Child, and S. Joseph, to which group approach from all sides a magnificent crowd of the attendants of the kneeling Magi. The first King, who is offering his homage, represents Cosimo, the elder. The other Kings are Piero (il Gottoso), and on the right, Giovanni di Cosimo. The black-haired youth with folded hands is Giuliano, who was slain in the Conspiracy of the Pazzi. On the left is Lorenzo, his avenger, who appropriately rests his hands on his sword-hilt. The figure on the extreme right is Sandro himself, looking at the spectator.

About this time Sandro received a commission to paint…an Adoration of the Magi. In the face of the oldest of the kings, the one who first approaches, there is the most lively expression of tenderness as he kisses the foot of the Saviour, and a look of satisfaction also at having attained the purpose for which he had undertaken his long journey. This figure is the portrait of Cosimo de’ Medici, the most faithful and animated likeness of all now known to exist of him. The second of the kings is the portrait of Giuliano de’ Medici, father of Pope Clement VII.; and he offers adoration to the divine Child, presenting his gift at the same time, with an expression of the most devout sincerity. The third, who is likewise kneeling, seems to be offering thanksgiving as well as adoration, and to confess that Christ is indeed the true Messiah: this is the likeness of Giovanni, the son of Cosimo. The beauty which Sandro has imparted to these heads cannot be adequately described, and all the figures in the work are represented in different attitudes: of some one sees the full face, of others the profile, some are turning the head almost entirely from the spectator, others are bent down; and to all, the artist has given an appropriate and varied expression, whether old or young, exhibiting numerous peculiarities also, which prove the mastery that he possessed over his art. He has even distinguished the followers of each king in such a manner that it is easy to see which belongs to one court and which to another; it is indeed a most admirable work: the composition, the design, and the colouring are so beautiful that every artist who examines it is astonished, and at the time, it obtained so great a name in Florence and other places for the master, that Pope Sixtus IV., having erected the [Sistine] chapel built by him in his palace at Rome, and desiring to have it adorned with paintings, commanded that Sandro Botticelli should be appointed Superintendent of the work.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 2, pp. 213–14.

Room A16 TRIBUNE

The second door on the left of the gallery leads into The Tribune, a room originally built between 1581-83 by Bernardo Buontalenti for the Grand Duke Ferdinand I. to contain a collection of precious stones, but now devoted to gems of painting and sculpture. Of the latter there are five Capi d’ Opera, viz.: Facing the Entrance. The Venus de’ Medici, a marble copy of a bronze Greek original, is one of the most celebrated specimens of the art of sculpture existing found in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli. It is the statue which Napoleon I. said he wanted to marry to the Apollo Belvidere. It is attributed to Cleomenes, son of Apollodorus the Athenian. Much restored by Ercole Ferrata in 1687; but perhaps deriving from a Praxitelean original.

Medici Venus, 1st-century BCE (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

We must return, and once more give a loose

To the delighted spirit worshipping,

In her small temple of rich workmanship,

Venus herself, who, when she left the skies, Came hither.

Samuel Rogers, Italy: A Poem.

Her modest attitude is partly what unmakes her as the heathen goddess and softens her into woman. On account of the skill with which the statue has been restored, she is just as whole as when she left the hands of the sculptor. One cannot think of her as a senseless image, but as a being that lives to gladden the world, incapable of decay or death; as young and fair as she was three thousand years ago, and still to be young and fair as long as a beautiful thought shall require physical embodiment.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, Note-Books, vol. 2, pp. 8–9, 22.

The goddess loves in stone, and fills

The air around with beauty; we inhale

The ambrosial aspect, which, beheld, instils

Part of its immortality; the veil

Of heaven is half undrawn; within the pale

We stand, and in that form and face behold

What Mind can make, when Nature’s self would fail,

And to the fond idolaters of old

Envy the innate flash which such a soul could mould.

We gaze and turn away, and know not where,

Dazzled and drunk with beauty, till the heart

Reels with its fulness; there for ever there

Chain’d to the chariot of triumphal Art,

We stand as captives, and would not depart.

Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto 4:50.

The Venus is without parallel, being the masterpiece of one whose name you see graven under it in old Greek characters; nothing in sculpture ever approached this miracle in art.

John Evelyn, Diary, vol. 1, pp. 139–140. John Evelyn (1644) saw the statue in the Villa Medici at Rome.

The Wrestlers, Roman copy of a 3rd c. BCE Greek original (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

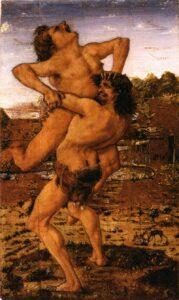

Two youthful figures are wrestling with the utmost might of a physical strength that has been trained in gymnastic exercise. Both are so ingeniously entwined in each other that the group is beautifully constructed, and yet the two figures are everywhere distinctly separable. The one thrown down seems for the moment to have the worst of it, though not to such an extent that the issue is already decided. On the contrary, the uncertainty of the result keeps the spectator in the same suspense as in similar scenes in the gymnasium. Art has here admirably transformed into marble one of those scenes which the Palaestra daily afforded to the attentive observer.

Wilhelm Lübke, History of Sculpture, vol. 1, pp. 239–240

Arrotino (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

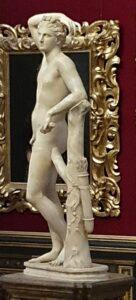

Apollino (photo via Wikimedia Commons)

L’Arrotino, the Scythian Slave whetting his knife (Pergamenian) found at Rome in XV. c.

Giorgio Sommer, Apolino

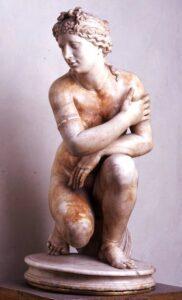

The god is conceived in the supple form of youth, and exhibits the same position of easy rest and self-indulgence which characterises several works by Praxiteles. The left arm, which probably held the bow, is supported against the stem of a tree, and the right arm is resting on the head. The figure thus acquires an extremely finely felt contrast in its whole outline, and produces the effect of almost dreamy ease.

Wilhelm Lübke, History of Sculpture, vol. 1, p. 192.

It is difficult to conceive anything more delicately beautiful than the Ganymede; but the spirit-like lightness, the softness, the flowing perfection of these forms, surpass it. The countenance, though exquisitely lovely and gentle, is not divine. There is a womanish vivacity of winning yet passive happiness, and yet a boyish inexperience exceedingly delightful. Through the limbs there seems to flow a spirit of life which gives them lightness. Nothing can be more perfectly lovely than the legs, and the union of the feet with the ankles, and the fading away of the lines of the feet to the delicate extremities. It is like a spirit even in dreams. The neck is long yet full, and sustains the head with its profuse and knotted hair as if it needed no sustaining.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, “The Figure of a Youth Said To Be Apollo,” Prose Works, vol. 3, p. 69.

The Dancing Faun (with restorations by Michelangelo), one of many ancient copies of a Praxitelean original.

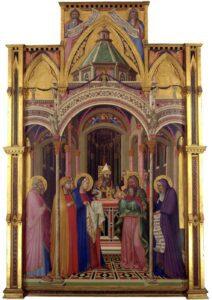

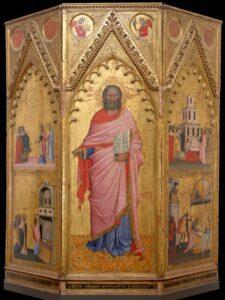

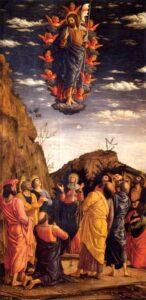

The Adoration of the Magi, with the Circumcision and the Ascension, a triptych which belonged to the Gonzago, who sold it to Antonio de’ Medici, Prince of Capistrano. A picture full of powerful and poetic detail.

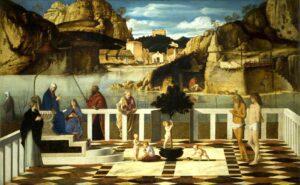

In an enclosed space the Virgin is enthroned, a female Saint on either side. Before her is the Tree of Life (?), from which nude children pluck fruit. Behind them stand SS. Onofrio and Sebastian, representing the old and youthful Saints. Over the paling, as though guarding the enclosure, lean SS. Peter and Paul. Beyond stretches a rocky landscape, with a lake of luminous water in the middle distance. Here are seen a centaur lying in wait for a monk, a negro in a hut, an Arab and other figures, apparently representing the faiths outside the pale of the Church. The colour is rich and sombre, blues and greens predominating. Formerly attributed to Basaiti. Brought from the Villa of Poggio Imperiale 1795.

Maud Cruttwell, Guide to the Paintings in the Florentine Galleries, pp. 26–27.

Room A20 15th Century in Emilia Romagna

Room A21 15th Century in Lombardia

Camillo Boccaccino (1505 – 1546), Portrait of an Old Man, 1630-c. 1640

Room A22 Bouvoir of Miniatures

A23 South Corridor

Baccio Bandinelli, who had been copying the Laocoon, boasted that he had surpassed the original. Upon which Michelangelo observed, “He whose own productions are indifferent knows not how to appreciate duly the works of others.”

J.S. Harford, Life of Michael Angelo, vol. 2, p. 223.

Domenico and Davide Ghirlandaio (1448 – 1494), Madonna and Child enthroned with Saints Dionysius the Areopagite, Dominic, Clement, Thomas Aquinas and angels, 1480-c. 83.

This charming picture, which was made to give Ghirlandajo the best hopes, helped, more than anything else, to procure him the encouraging distinction of being called to Rome to decorate the Sistine Chapel.

Alexis-François Rio, L’Art Chrétien, p.

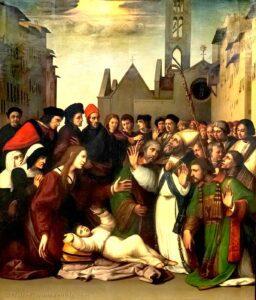

Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449 – 1494), Adoration of the Magi, 1487. Highly finished landscape. A Madonna enthroned. Ridolfo Ghirlandaio (son of Domenico, 1483–1561), The Miracle of S. Zanobio in Via degli Albizzi.

Extraordinary liveliness and nature stamp the movements and expressions of the eager and wondering crowd which presses around the kneeling bishop, as with uplifted arms he restores to life the fallen boy.

Crowe and Cavalcaselle, New History of Painting in Italy, vol. 3, p. 527.

Ghirlandaio, The Funeral of S. Zanobio.

It is related that when they were bearing the remains through the city in order to deposit them under the High Altar of the Duomo, the people crowded round the bearers and pressed upon the bier in order to kiss the hands or touch the garments of their beloved old Bishop. In passing through the Piazza del Duomo, the body of the saint was thrown against the trunk of a withered elm standing near the spot where the Baptistery now stands, and suddenly the tree, which had for years been dead and dried up, burst into fresh leaves.

Anna Jameson, Sacred Art and Legendary Art, vol. 2, p. 703.

The connection existing between a coffin which passes, and a tree which renews its foliage, could only be explained by a verbal narration, and therefore belonged rather to the domain of legendary poetry than to that of art. With regard, however, to execution and general character this picture leaves us nothing to desire; and I doubt if the Florentine school has ever produced anything so perfect for beauty of colouring.

Alexis-François Rio, Poetry of Christian Art, p. 294.

No careful and grateful student of this painter can overlook his special fondness for seasides: the tenderness and pleasure with which he touches upon the green opening of their chimes or coombs, the clear low ranges of their rocks. This picture bears witness to this. Beyond the farthest meadows and behind the tallest trees, far-off downs and cliffs open seaward, and farther yet pure narrow spaces intervene of gracious and silent sea.

Algernon Charles Swinburne, Essays and Studies, p. 332.

In this beautiful tondo, the painter, instead of merely adapting the figures of the sacred family to a circular space, conceives them as though sculptured in stone, or viewed through a round window. Mary reads the holy truths to the Child, while Joseph with arms crossed upon his breast and kneeling on one knee, listens, head bent. The Child surprised (as though by an idea) and ceasing to listen, turns his head toward his earthly father and raises his left hand. The figure of Joseph is very fine, as that of strong and simple old peasant-monk; while that of the Virgin is dignified and lovely, intent upon the reading. Her head is apparently that of the second figure on the left in the example of this master in the National Gallery in London.

Adolfo Venturi, Storia dell’ Arte Italiana.

Luca Signorelli, Allegory of Abundance (in grisaille).

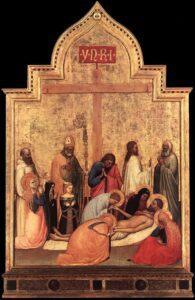

Luca Signorelli, A Crucifixion and Deposition.

Luca Signorelli, A Predella, with the Annunciation, Nativity and Magi; from Montepulciano.

Luca Signorelli, Virgin and Child in a meadow: from the Medici Villa at Castello.

In this Madonna the spiritual parent of Michelangelo announces himself already to those who can understand. There is nothing unusual in the figure of the Virgin in dark red and dark blue, who, as she sits, half turns round to hold with both hands the child standing at her feet. What is unusual is the little group in the background. For the customary shepherds, there stand four naked figures modelled in strong light and shade, and showing that this, the unclothed frame and anatomy of men, is the thing the painter cares for and will have, wherever he can get it.

S. C. [St. Clair Baddeley]

Andrea del Verrocchio, The Baptism of Christ, 1472-75. From S. Salvi. This is the work (always rare) of Leonardo’s master and the sculptor of the Colleoni statue at Venice.

The subject of this picture is the Baptism of Christ by St. John, and being assisted in it by Leonardo da Vinci, then a youth and Andrea’s disciple, the former painted therein the figure of an angel, which was much superior to the other parts of the picture. Perceiving this, Andrea resolved never again to take pencil in hand, since Leonardo, though still so young, had acquitted himself in that art better than he had done.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 2, p. 245.

A picture representing the Adoration of the Magi was likewise commenced by Leonardo, and is among the best of his works, more especially as regards the heads; it was in the house of Amerigo Benci, opposite the Loggia of the Peruzzi, but like so many of the other works of Leonardo, this also remained unfinished.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 2, p. 382.

Raffaelle, Portrait of Julius II. There is a replica of this picture in the Palazzo Pitti. Morelli thinks this one may be the original, in spite of its much repainting.

At this time, also, our artist, who had now acquired a very great name, depicted the portrait of Pope Julius himself. This is an oil painting, of so much animation and so true to the life, that the picture impresses on all beholders a sense of awe as if it were indeed the living object.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 3, p. 160.

Dur et violent Génois, variable comme le vent de Gênes.

A Genoese hard and violent, variable like the wind from Genoa.

Jules Michelet, Histoire de France, vol. 7, p. 161.

In Rome, Raphael likewise painted a picture of good size, in which he represented Pope Leo, the Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici,5Future Pope Clement VII. and the Cardinal de’ Rossi. The figures in this work seem rather to be in full relief, and living, than merely feigned, and on a plane surface. The velvet softness of the skin is rendered with the utmost fidelity; the vestments in which the Pope is clothed are also most faithfully depicted, the damask shines with a glossy lustre; the furs which form the linings of his robes are soft and natural, while the gold and silk are copied in such a manner that they do not seem to be painted, but really appear to be silk and gold. There is also a book in parchment decorated with miniatures, a most vivid imitation of the object represented, with a silver bell, finely chased, of which it would not be possible adequately to describe the beauty. Among other accessories, there is, moreover, a ball of burnished gold on the seat of the Pope, and in this—such is its clearness—the divisions of the opposite window, the shoulders of the Pope, and the walls of the room, are faithfully reflected; all these things are executed with so much care, that I fully believe no master ever has done, or ever can do any thing better. For this work, Raphael was richly rewarded by Pope Leo.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 3, pp. 180–81.

Raffaelle, S. John In the Wilderness. Painted for Cardinal Pompeo Colonna. Said to be the only picture painted by the master on canvas; but most authorities attribute only the design to Raffaelle, the painting to Giulio Romano and Penni.

For the Cardinal Colonna, Raphael painted a San Giovanni on canvas, which was an admirable work and greatly prized for its beauty by the cardinal, but the latt being attacked by a dangerous illness, and having been cured of his infirmity by the physican Messer Jacopo da Carpi, the latter desired to be presented with the picture of Raphael as his reward; the cardinal, therefore, seeing his great wish for the same, and believing himself to be under infinite obligation to his physician, deprived himself of the work, and gave it to Messer Jacopo.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 3, p. 209.

[St. John] nude, a fine youthful form of fourteen, healthy and vigorous, in which the purest paganism lives over again

Hippolyte Taine, Florence, p. 140.

Raffaello Sanzio La Madonna del Cardellino (Madonna of the Goldfinch), was painted, on commission, for Lorenzo Nasi. It was buried in the fall of his house at S. Giorgio in 1548, and restored by Battista Nasi, son of Lorenzo, but not ruined.

Raphael also formed a close friendship with Lorenzo Nasi;, and the latter, having taken a wife at that time, Raphael painted a picture for him, wherein he represented Our Lady, with the Infant Christ, to whom San Giovanni, also a child, is joyously offering a bird which is causing infinite delight and gladness to both the children.This picture was held in the highest estimation by Lorenzo Nasi so long as he lived, not only because it was a memorial of Raphael, who had been so much his friend, but on account of the dignity and excellence of the whole composition: but on the 9th of August, in the year 1548, the work was destroyed by the sinking down of the hill of San Giorgio; when the house of Lorenzo was overwhelmed by the fallen masses together with the beautiful and richly decorated dwelling of the heirs of Marco del Nero, and many other buildings. It is true that the fragments of the picture were found among the ruins of the house, and were put together in the best manner that he could contrive, by Battista the son of Lorenzo, who was a great lover of art.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 3, p. 136.

The divine goodness expressed in the countenance of the Child Jesus, whilst he holds his hands over the little bird, and seems to say, “Not one of these is forgotten by my Father,” is beyond all description.

Fredrika Bremer, Life in the Old World, vol. 2, p. 49.

One of the most charming of his early works.

Giovanni Morelli, Italian Painters…in Rome, p. 37.

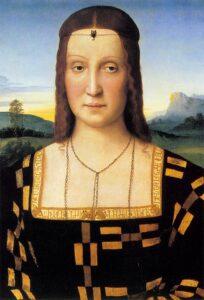

Raffaello, Portraits of Agnolo and Maddalena Doni (front); the Flood and Deucalion and Pyrrha (back), c. 1504-07. The portraits of Angelo Doni (one of the master’s finest portraits) and his wife (Maddalena Strozzi) were preserved by their descendants in the family mansion in the Via dei Tintori till the death of its last member, Pietro Buono, in the present century. They then passed into the hands of the Doni of Avignon, who sold them to Leopold II. in 1826.

Maddalena Doni, sits in sad and serene indifference. Observe the exquisite details of her dress and chair. Much repainted. Hare believed that the portrait was neither by Raffaelle nor did it represent Maddalena Doni.

The Florentine citizen, Agnolo Doni, likewise desired to have some production from the hand of Michelagnolo, who was his friend, and he being, as we have before said, a great lover of fine works in art, whether ancient or, modern; wherefore Michelagnolo began a circular painting of Our Lady for him; she is kneeling, and presents the Divine Child, which she holds in her arms, to Joseph, who receives him to his bosom. Here the artist has finely expressed the perfection of delight with which the mother regards the beauty of her Son, and which is clearly manifest in the turn of her head and fixedness of her gaze: equally obvious is her wish that this contentment shall be shared by that pious old man who receives the babe with infinite tenderness and reverence. Nor did this suffice to Michelagnolo, since the better to display his art, he has assembled numerous undraped figures in the back-ground of his picture, some upright, some half recumbent, and others seated. The whole work is, besides, executed with so much care and finish, that of all his pictures, which indeed are but few, this is considered the best. When the picture was completed, Michelagnolo sent it, still uncovered, to Agnolo Doni’s house, with a note demanding for it a payment of sixty ducat. But Agnolo, who was a frugal person, declared that a large sum to give for a picture, although he knew it was worth more, and told the messenger that forty ducats which he gave him was enough. Hearing this, Michelagnolo sent back his man to say that Agnolo must now send a hundred ducats or give the picture back; whereupon Doni, who was pleased with the work, at once offered the sixty first demanded. But Michelagnolo, offended by the want of confidence exhibited by Doni, now declared that if he desired to have the picture, he must pay a hundred and forty ducats for the same, thus compelling him to give more than double the sum first required.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives, Trans. Blashfield, vol. 4, pp. 62-64.

The nine persons who make up the picture are all carefully studied from the life, and bear a strong Tuscan stamp. S. John is literally ignoble, and Christ is a commonplace child. The Virgin Mother is a magnificent contadina [peasant woman] in the plenitude of adult womanhood.

J.A. Symonds, Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti, vol. 1, p. 116.

I saw nothing here so grand as the group of Niobe, if statues which are now disjointed and placed equidistantly round a room may be so called. Niobe herself, clasped by the arms of her terrified child, is certainly a group; and whether the head be original or not, the contrast of passion, of beauty, and even of dress, is admirable. The dress of the other daughters appears too thin, too meretricious, for dying princesses. Some of the sons exert too much attitude. Like gladiators, they seem taught to die picturesquely, and to this theatrical exertion we may, perhaps, impute the want of ease and undulation which the critics condemn in their forms.

Joseph Forsyth, Remarks, p. 58.

Ultima restabat; quam toto corpore mater, Tota veste tegens, Unam, minimamque relinque! De multis minimam posco, clamavit, et unam.

the last remained. The mother, covering her with her crouching body and her sheltering robes, cried out “Oh, leave me one, the littlest! Of all my many children, the littlest I beg you spare—just one!”

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Trans. Frank Justus Miller, 6:298–300.

This figure of Niobe is probably the most consummate personification of loveliness with regard to its countenance, as that of the Apollo of the Vatican is with regard to its entire form, that remains to us of Greek antiquity. It is a colossal figure; the size of a work of art rather adds to its beauty, because it allows the spectator the choice of a greater number of points of view, in which to catch a greater number of the infinite modes of expression of which any form approaching ideal beauty is necessarily composed, of a mother in the act of sheltering from some divine and inevitable peril the last, we will imagine, of her children.

The child, terrified, we may conceive, at the strange destruction of all its kindred, has fled to its mother, and hiding its head in the folds of her robe, and casting up one arm as in a passionate appeal for defence from her, where it never before could have been sought in vain, seems in the marble to have scarcely suspended the motion of her terror, as though conceived to be yet in the act of arrival. The child is clothed in a thin tunic of delicatest wool, and her hair is gathered on her head into a knot, probably by that mother whose care will never gather it again. Niobe is enveloped in profuse drapery, a portion of which the left hand has gathered up and is in the act of extending over the child in the instinct of defending her from what reason knows to be inevitable. The right—as the restorer of it has justly comprehended—is gathering up her child to her, and with a like instinctive gesture is encouraging by its gentle pressure the child to believe that it can give security. The countenance, which is the consummation of feminine majesty and loveliness, beyond which the imagination scarcely doubts that it can conceive anything, that masterpiece of the poetic harmony of marble, expresses other feelings. There is embodied a sense of the inevitable and rapid destiny which is consummating around her as if it were already over. It seems as if despair and beauty had combined and produced nothing but the sublime loveliness of grief. As the motions of the form expressed the instinctive sense of the possibility of protecting the child, and the accustomed and affectionate assurance that she would find protection within her arms, so reason and imagination speak in the countenance the certainty that no mortal defence is of avail.

There is no terror in the countenance—only grief, deep grief. There is no anger—of what avail is indignation against what is known to be omnipotent? There is no selfish shrinking from personal pain; there is no panic at supernatural agency; there is no adverting to herself as herself; the calamity is mightier than to leave scope for such emotion.

Everything is swallowed up in sorrow. Her countenance, in assured expectation of the arrow piercing its victim in her embrace, is fixed on her omnipotent enemy. The pathetic beauty of the mere expression of her tender and serene despair, which is yet so profound and so incapable of being ever worn away, is beyond any effect of sculpture. As soon as the arrow shall have pierced her last child, the fable that she was dissolved into a fountain of tears will be but a feeble emblem of the sadness of despair, in which the years of her remaining life, we feel, must flow away.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, “The Niobe”, Prose Works, vol. 3, pp. 73–76.

O Niobe, con che occhi dolenti

Vedev’ io te segnata in su la strada

Tra sette e sette tuoi figliuoli spenti!

O Niobe! with what afflicted eyes

Thee I beheld upon the pathway traced,

Between thy seven and seven children slain!

Dante Purgatorio 12:37–39. Trans. Longfellow.

Orba resedit

Exanimes inter natos, natasque, virumque,

Diriguitque malis. Nullos movet aura capillos,

In vultu color est sine sanguine, lumina maestis

Stant immota genis: nihil est in imagine vivum.

And even while she prayed, she for whom she prayed fell dead. Now does the childless mother

sit down amid the lifeless bodies of her sons, her daughters, and her husband, in stony grief.

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Trans. Frank Justus Miller, 6:301–305.